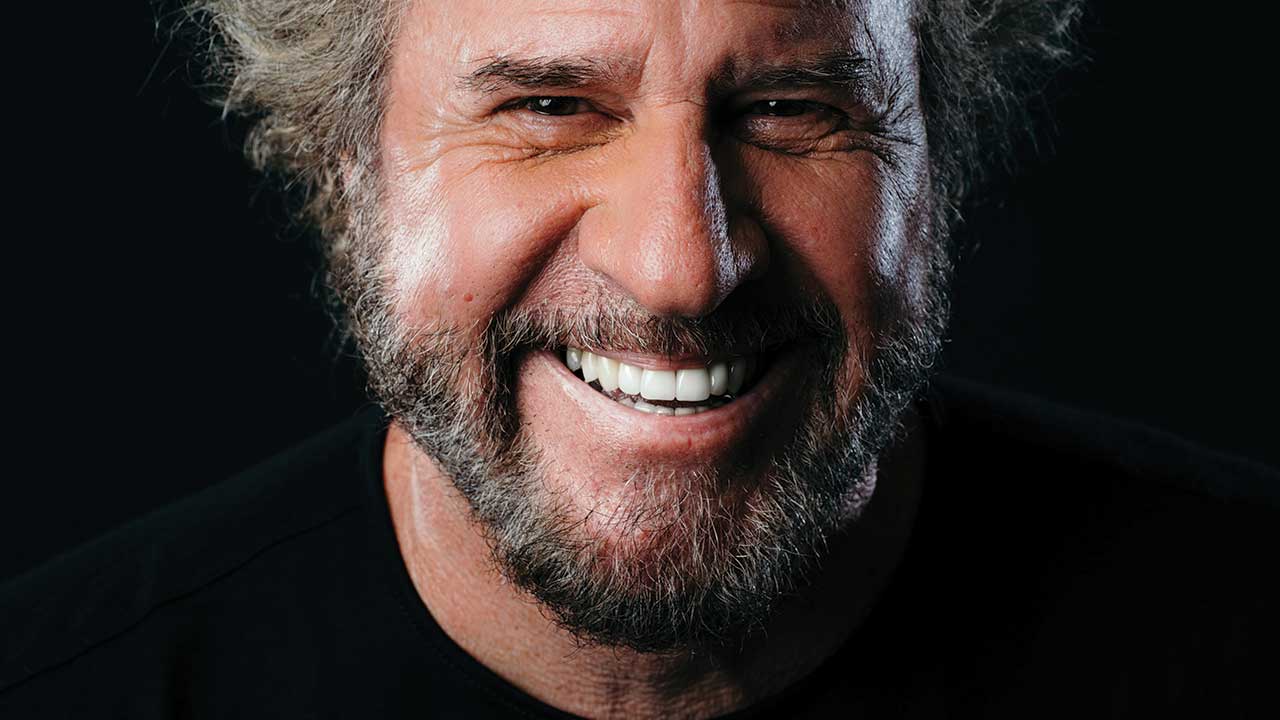

Sammy Hagar interview: Diamond Dave, the Van Halens, and a long life in rock

At the age of 71, tequila multimillionaire Sammy Hagar can look back on an extraordinarily successful life in music – Montrose, Van Halen, Chickenfoot, The Circle and more

Sammy Hagar decided to grab hold of life a long time ago, and he hasn’t let go since. Even at 71, the singer/guitarist/ tequila magnate/alien abductee has enough energy to power America’s entire Western seaboard.

“I don’t know what the fuck is wrong with me,” he says. “But I plan on making it to a hundred, so I’ll be the oldest living rock star on the planet some day.”

That’s a few years away. Right now, Hagar’s limitless enthusiasm is directed towards The Circle, the band he put together with drummer Jason Bonham, guitarist Vic Johnson and bassist/fellow Van Halen refugee Michael Anthony. The Circle were initially formed to play choice cuts from Hagar’s illustrious back catalogue – Montrose, Van Halen, Chickenfoot plus his various solo albums, with a side order of Led Zeppelin courtesy of Bonham Jr.

“We play the Van Halen stuff as well as Van Halen ever played it, we play Rock Candy as good as Montrose ever played it,” he says. “That’s a mighty bold statement, but it’s a fact. So I thought: ‘We’ve got twenty classic songs from each band, probably more, we don’t even need to make a record.’ But five years later, here we are, we made a record.”

That record, his twenty-seventh, is Space Between. Like pretty much all of its predecessors, it’s the soundtrack to the best party you’ve never been to, with Hagar’s undiminished roar at the heart of it. But there’s something deeper going on this time: Space Between is his first concept album.

"It’s been brewing for a while,” he says. “It’s about the division between good and bad. All these big corporate guys that are billionaires to begin with, ripping off their employees; people bombing churches; the Right hating the Left, the Left hating the Right, the blacks hating the whites. It used to be that you could go to hell, the devil was somewhere else. But the devil is at sea level now. The solution lies in the space between us – that handshake in the middle.”

A late-career concept album isn’t so outlandish – the reported $80 million windfall Hagar received from selling his Tequila company a decade ago provides a nice fallback if things don’t work out. But you get the sense that even without that, Sammy Hagar is the kind of person who does whatever the hell he wants to anyway.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Damn right,” he says with a laugh.

Let’s go right back to the start. Can you remember the very first time you stepped on stage?

Not exactly. But I remember when I was about fifteen the band I was in being hired to play a party. And I fucking loved it, man: “This is what I want to do.” I would carry my amplifier and guitar all the way across town to rehearse in my friend’s garage. That’s probably why my back’s half-broken.

There were lots of years of struggle before you joined Montrose in 1973. Did you ever come close to quitting?

No, absolutely not. There was no quitting for me. Even if we’d be sleeping on someone’s floor, no pillow, after playing until two o’clock in the morning, I’d think: “I’m waking up in the morning and I want to make it.”

The only time I got disappointed when was when I was in the Justice Brothers, this soul band. I said: “I’m gonna write songs,” and I wrote Make It Last and Bad Motor Scooter.

I said: “Let’s start dressing crazy and shit.” And they turned on me: “We’re not doing that.” But I didn’t think: “I’m fucked. I’m quitting.” I just said I’m looking for another band. And as soon as I put the feelers out, Ronnie Montrose called me.

What did you make of Ronnie the first time you met him?

I thought he was the coolest guy on the frickin’ planet. And he was. I saw the last show he played with the Edgar Winter Band at Winterland in San Francisco. This was after those other guys told me they didn’t want to play the songs I’d written. I said: “That’s the kind of guitar player I want to have.” I got his number, and drove five miles in my battered truck and knocked on his door.

The first songs you wrote were Make It Last and Bad Motor Scooter, and the first album you made was Montrose’s debut. That’s a hell of a start.

Man, I know! When I look back, I think it was a miracle. I had an astrologer do my chart just before, and he goes: “Something happened to set you on your path, and it’ll carry on for eighty-one years.” I was twenty-four, twenty-five then, so I guess I’ll carry on doing this until I’m a hundred and five.

What was your relationship with Ronnie like? Did you actually get on with him? I tried.

I tried so hard to bring him close, but he was a distant person. He had four or five marriages, he changed band members the second he started getting the tiniest bit of success… It’s like he was afraid of getting close, even when he was hurting. The second you got serious he’d start talking about sex or something to throw it off. He would never let you find out who he really was.

So when he committed suicide it was the horriblest thing. I couldn’t believe it. But at the same time, we knew it was just a matter of time. He would not let anyone help him. He would not.

What did you learn from him?

Oh, fuck. I learned how to play that style of guitar. I played with Eddie Van Halen, I played with Neal Schon, I played with Joe Satriani – I don’t play anything like those guys. But I still play like Ronnie Montrose. He had that profound influence on me.

You left Montrose in 1975. What happened?

We were in Paris, headlining two nights at the Olympic Auditorium. We were in a station wagon – Ronnie sitting shotgun, me sitting behind him. I was sick as a dog – the flu or food poisoning or something. He turned round and said: “I’m quitting the band after this show.” We parked the car in the back of the venue, and he said: “What are you gonna do?” I said: “You motherfucker. What do you think I’m gonna do? I’m gonna start a new band, that’s what.”

Karma’s such a weird thing, because something got me out of that band and it’s the best thing that ever happened. It must have hurt, though. I was devastated, man. I came home, my phone was shut off, I was back two months rent on the house I was living in, I had a wife and child. I immediately went on unemployment and welfare, and I started calling friends saying: “I’m starting a band.”

I reached out to the people around me who were just as desperate as me. I couldn’t afford to hire anyone, I just asked them if they wanted to start a band. It was tough, but I was never, ever helpless and crying. I was fucking getting up in the morning and going to work. Man, no one’s ever gonna outwork me, I can tell you that.

It took a few years for your solo career to get up to full speed. Was it a struggle?

It was a financial struggle, cos I was trying to pay a band and pay our roadies. But I was lucky that I had a record company, Capitol, and a producer, John Carter, who signed me for three albums. I’d make an album, go out on tour, make album… It was hard work, but I really don’t mind hard work. I enjoy it.

And I had enough money to live on. In Montrose we had no money. We’d get in a hotel room and they wouldn’t fucking let us out cos Ronnie’s credit card was maxed. We’d have to sit in the room until the manager wired the money so we could leave. That was how poor Montrose was.

Is it true that Van Halen’s producer, Ted Templeman, suggested they get you in as singer even before they started work on their first album?

Yes. It never got to me until I worked with Ted on my VOA record. I thought: “Wow, nobody called me.” If I’d heard Eddie Van Halen play, I would have said: “Fuck yeah!” Mikey [Michael Anthony, VH bassist] told me he knew about it. I guess Dave [Lee Roth, original VH singer] knew about it too. Maybe that’s why he still doesn’t like me.

You finally got your big breakthrough with your sixth solo album, Standing Hampton. What changed?

David Geffen [founder of the newly created Geffen Records] signed me. He only had John Lennon and Donna Summer and Elton John at that time, and now he’s signed Sammy Hagar. I like that kind of company, so I stepped up. I put on some brand new shoes and said: “I’m here, I’m ready to do this.” Then [heavyweight A&R man] John Kalodner said: “Here’s a million dollars to make this record. I’m not gonna let you out of your fucking house until you’ve given me twenty great songs.”

So I got my band over here every day and I wrote and wrote. We did twenty-eight songs for Standing Hampton. John said: “That one’s good, that one ain’t. Keep writing.” He elevated the whole thing. Did success go to your head? No. Most artists, fame and fortune ruins them. As soon as they start making it, they lose it. It’s a black hole. But fame and fortune makes me hungrier. Not for greedy reasons, but because I want to stay on top.

And staying on top calls for keeping your fucking sleeves rolled up and your hard hat on, getting in that tunnel and going to fucking work. So every time I got a break, I didn’t say: “Oh boy, I’m rich. I don’t have to do this any more,” I said: “I’m gonna live up to this.” I’m rich now, but I still see it like that.

And then in 1985 you joined Van Halen. Day one in the rehearsal room with those guys – what was it like?

Oh, I can tell you exactly what it was like. At that stage I had a good career going, I was wealthy, I was eating in the finest restaurants and wearing the finest fucking clothes, I was driving Ferraris. I was becoming a little too sophisticated – it was killing my music. Whereas those guys were living a completely different lifestyle.

Long story short, I walked in that room and these guys had cigarette butts and empty beer cans and whiskey bottles everywhere, multi-thousand-dollar guitars lying upside-down on the ground. And it stunk like shit because of the smoke. Eddie comes walking out with a pair of sunglasses, jeans with holes in them, just outta bed, cracking a beer and smoking a cigarette. Alex was still drunk. Mike hadn’t even been home.

They’d been up all night waiting for me. I’m looking at these guys, then I’m looking at myself in a suit, and I go: “I look like a fucking idiot. This is a real rock’n’roll band.”

“I’m afraid if I ever reached out and really tried to contact Ed and Al, they’d think that I was trying to get back in the band.”

Sammy Hagar

Did you start jamming right away?

Yeah, we just cranked up. They had written some ideas for the music to Summer Nights and Good Enough, and I just start scatting and singing. Alex is making fun of my haircut, cos I’d just had most of it shaved off apart from a little poodle pouf on top. And I’m going: [jokingly] “Fuck you guys, let’s step outside…”

We ran cassettes all day, recording what we did. I got home at two in the morning and played one of these cassettes, and it was so rock’n’roll. I went: “Fucking wow, I’m joining this band right away!”

And I’m so glad I did. It changed my life, because otherwise I would be some guy fucking walking around in suits and shit. Van Halen took me back to the rock’n’roll.

Was there ever any doubt in your mind that it wouldn’t work out?

I was too confident for that. We all were. The record company weren’t. They were saying we should name the band Van Hagar, just in case it goes wrong – they could always go back to Van Halen and not take the whole band down. We didn’t let the label in the studio. We made that whole 5150 record, and then we invited [Warner Bros Records boss] Mo Ostin, one of the greatest record company presidents in history, down.

They walk in, it’s me on guitar and Eddie on keyboard, and they’re, like: “What the fuck are you guys doing?”’ But we played Why Can’t This Be Love? live, right there for them. And after we’d done, Mo Ostin raises his finger in the air and says: “I smell money!” When the album came out it went straight to number one. We took that rock’n’roll highway and did it all. And until it turned bad, it was the greatest thing on the planet.

You were in Van Halen for ten years first time around. During that period did the good outweigh the bad?

Of course. The good was a million times better than the bad. The bad was such a short, one-year thing that when it went bad, it was just, like, [baffled]: “What just happened?” What did happen? Well, our manager, Ed Leffler, God rest his soul, died. And the music started suffering because we were arguing.

It was like: “Fuck, this is way too hard.” I told my wife: “I want out of this band, but I can’t quit because I love it too much, it’s too important.” And I hung on until they threw me out.

When was the last time you spoke to the Van Halen brothers?

As crazy it as it seems, the last time I spoke directly to them was after the last show on the 2004 reunion tour, the Best Of Both Worlds. We played Tucson, Arizona, and we walked off stage and said: “See you later.” We all got our private planes home, and we never talked again. I’ve tried. I’ve reached out a couple of times.

About three or four years ago I wished Eddie a happy birthday on Instagram, and he got back to me – or his Instagram person did – and said: “Hope you’re doing well, thank you.” And that was it. That’s the way it is.

Do you miss them?

Yeah. But it’s okay. And now I’m afraid if I ever reached out and really tried to contact Ed and Al, they would think that I was trying to get back in the band or I was trying to do a reunion. And I’m not. I am so content with The Circle. We play the Van Halen songs that I wrote with Ed as good as anybody, but I’m happy to have just five or six Van Halen songs in my set. It’s almost like I don’t want to be asked to do it, because I’d feel like I had to do it, but I don’t really want to. I’m sorry I don’t.

Can we talk Dave Lee Roth?

[Laughing] Oh yeah…

The two of you toured together in 2002, and it got quite fractious. Was that for real, or was it played up for the public?

It got totally played up. There wasn’t any animosity. Well, there was one crazy moment in Raleigh, Carolina where Dave flipped out.

What happened?

So, we were flip-flopping as headliners. When Dave opened he was much better off. I had Michael Anthony in my band, we played four or five Van Halen songs, I had my waitresses come out and bring us drinks during the show – half-naked. Dave did all his ’83/84 stuff with the scarves and stuff. It was like a karaoke band compared to what we were doing. He’d be in a bad mood when he was headlining, cos you cannot follow us.

So one night he’s walking to the stage, all dressed up, and my drummer went: “How’s it going, ladies…” He meant to add “…and gentlemen”, but it came out too late. Dave fucking flipped: “Fuck you, you motherfucker.” His bodyguards started pushing people around. I come out of my dressing room, naked apart from a towel, like: “Damn, Dave, you need to settle down and have a good show, brother.”

So they ended up building a barricade between us. But yeah, it was overplayed. Dave and I don’t hate each other. If we saw each other we’d hug and buy each other a drink. [Laughing] I don’t know how long we’d hug for, but we’d hug.

Michael Anthony…

[Interrupting] You mean the greatest background vocalist bassist in rock’n’roll?

That’s the one. He was hung out to dry by the Van Halen brothers when they didn’t invite him to be part of the Dave Lee Roth reunion, but you had his back.

I can’t stand any form of disrespect or disloyalty. I hated seeing him get fucked around, so I had to step up and say: “No, no, no, no, no, no.” Michael Anthony is a motherfucker. He wasn’t utilised in Van Halen enough, because Eddie’s playing is so busy. But I’m telling you, you cut that guy loose and he’s got chops. He can play ’em and he can sing ’em.

You’re a people person, right?

It’s true. I love my fans, I love my family, I love my friends, I even love my enemies. I love Ronnie Montrose – he wasn’t an enemy, but he never became my closest friend. Eddie Van Halen, who was my closest friend, we had a falling out, but I still love the guy. Alex too. If I ran into those guys, I would really want to hug them. We’d probably get all teary eyed and shit, because they know it. I go through my life making friends, not enemies. I won’t let people who I think would fuck me over into my life.

Since you left Van Halen first time around, you’ve done a reunion tour, made twelve albums of your own, opened a string of bars, started then sold a tequila company for eighty million dollars, started a rum company, made radio and TV shows… When do you find time to sleep?

Oh, I sleep, man. I love the bedroom. I’m not a couch guy. When I hit the bed I like rolling around with my wife and then having a good night’s sleep. Then I get up and have me some breakfast and I’m rollin’. But I know good people. I always make sure I have a good team around me.

What happened to Chickenfoot?

Well, it was such a hard band to find time for. That band was all about the chemistry, and Chad Smith [Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer who played on the first Chickenfoot album] was such an important part of that. Every time the Chili Peppers did a record, they’d go out and tour for five fucking years.

We had to do the second album without him, and it wasn’t the same. No disrespect to Kenny Aronoff [who played on the second album], but it was about the four of us.

Do you think you’ll ever reactivate Chickenfoot?

I’m doing a show in September, and I tried to get Chickenfoot to headline the second night, but Chad’s playing a festival with the Chili Peppers. I just told Joe [Satriani] this morning and he went: “Fuck, man.” He was so disappointed, cos he loves Chickenfoot as much as I do. I would like to do that, but there’s just too much going on with this Circle record. I want people to think it’s as good as I think it is.

Have you seen the internet meme comparing you and Bill Clinton, where you look amazing and he… well, he doesn’t?

[Erupting with laughter] Yes I have. God help the fucker. He was President Of The United States, the worst job on the planet. Who would want that job?

So when will Sammy Hagar retire?

Well, I’m gonna do this till I’m a hundred or a hundred and five. But seriously, I’ll know when I’m not good any more. When that happens, I will definitely quit. I will not go out and do bad shows. The day I walk out there and I don’t have it, I will quit faster than anybody in this business. There will not be a farewell tour.

If you could apologise to one person, who would it be?

I don’t know if I owe anyone an apology, cos I don’t think I’ve ever done anything bad to anybody. I would say I’m sorry to Eddie and Alex if that would make them feel better, but I don’t feel like I did anything to hurt them.

You’ve talked in the past about being abducted by aliens, which made you sound crazy. Do you regret putting that out there?

Oh fuck no. I’m a straight up honest guy. I had an alien experience. And I’ve had more than one. Anyone that doesn’t believe that there’s other life in this universe, those are the crazy people. It’s a big universe out there. I wouldn’t doubt if I was living six different lives in different dimensions right now. That’s physics. If we are the only ones, that would scare me to fucking death. I welcome aliens into my life. I’m here! Take me for a ride!

If aliens did get in touch again, and they asked you to play them the best Sammy Hagar album from any era, which one would it be?

The new one, Space Between, because I would want them to see how far I’ve come since our last visit.

Is it as much fun being Sammy Hagar as it looks?

Oh fuck yeah. I’m not gonna lie to nobody. I still have more fun than anybody on the planet. My mind still works, my voice still works, my dick still works, my heart is still good and I got a memory, I’m rich and famous and I got a beautiful family.

Dude, if you see me going around with a bad look on my face, hit me on the shoulder and say: “Aren’t you Sammy Hagar?” And I’ll say: “Oh yeah, you’re right!”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.