"I always thought power metal is cheesy. We are not cheesy, **** that." Pumpkins, power metal and the most unexpected reunion in metal: Helloween are better than ever

How Helloween's Pumpkins United has reinvented power metal's first breakout stars

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

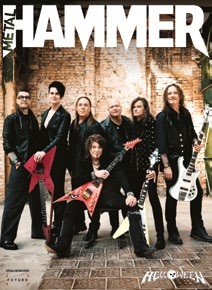

One of the most unexpected peace treaties of the 21st century was signed in 2016. On one side of the table was the current line-up of Helloween – co-founding guitarist Michael Weikath and bassist Markus Grosskopf, plus second guitarist Sascha Gerstner, drummer Daniel Löble and longtime singer Andi Deris. On the other side of the table were former Helloween guitarist Kai Hansen and singer Michael Kiske.

The latter duo had been part of the band that recorded 1987’s epic Keeper Of The Seven Keys: Part I and its equally magnificent 1988 sequel, Keeper Of The Seven Keys: Part II, two bona fide power metal landmarks that briefly threatened to turn these pumpkin-fixated Germans into the new Iron Maiden.

Even a few years earlier this situation would have been unthinkable. Acrimony had surrounded Kai and especially Michael Kiske’s respective departures in 1989 and 1993. Helloween themselves had weathered the loss of these two talismanic figures, though they never again reached the heights of the late 80s. But here they were, seven men who were about to put aside any lingering differences and form a brand new supergroup, albeit a supergroup featuring members of the same band from different times.

“I thought maybe we could do a tour together,” says Kai Hansen, one of the men who founded this institution more than 40 years ago. “But miraculously, it went so well that we decided to keep it going.”

Amazingly, the seven-man formation has held fast. They’re about to release their second album together (and 17th Helloween album in total), the exhilarating Giants & Monsters. It’s a weird, wonderful set-up.

“Yeah,” agrees co-vocalist Andi Deris. “But Helloween have always been a little bit weird and wonderful.”

Kai Hansen was a 21-year-old kid who drove a handpainted black car with studs on the steering wheel when he co-founded Helloween in 1984 with Michael Weikath, Markus Grosskopf and original drummer Ingo Schwichtenberg. The four of them had played with each other in various bands on the city’s small but fertile heavy metal scene, but their sights were set fairly low.

“My biggest ambition was to play the Hamburg Markthalle,” says Kai, referring to a celebrated 1,000-capacity venue in the band’s hometown. “I never had any intention of becoming a rock star or making big money from this.”

The ebullient guitarist is speaking to Hammer from Slovakia, where he lives. He knocks back a shot of Slovak gin as we start. “My daily ritual,” he says cheerfully.

By contrast, Michael ‘Weiki’ Weikath is sitting outside a hotel, chain-smoking cigarettes and occasionally shouting at the delivery trucks reversing into the goods entrance of a supermarket just off camera. He’s an entertainingly eccentric interviewee, all sweeping hand gestures, exaggerated facial expressions and entertainingly unfiltered opinions.

“We weren’t exactly friends, we were partners in crime,” says Weiki of his relationship with Kai in Helloween’s early days. “We were teaming up as a necessary evil.”

At first, Kai pulled double duty as guitarist and vocalist. “I was never a great singer, I was just screaming out what I felt,” he says. “It was a very naive form of expression.”

“It was exciting, but it was also kind of hard and stressful,” says Weiki of those formative years. “We were rehearsing every day of the week, except for Sunday when we would still meet and get drunk.”

There were some memorable early gigs, many involving homemade pyro. At one show, they blew up trash cans onstage. At another, Kai lobbed fake hand grenades into the crowd.

“They just went ‘Pffft!’, but everybody freaked out,” he recalls gleefully. “That was heavy metal.”

Helloween’s first, self-titled EP and debut full-length album, Walls Of Jericho, (both released in 1985) were melodic but fast and brittle – two parts Iron Maiden to one part Kill ’Em All-era Metallica, with the odd slice of Teutonic cheese for laughs (one song was titled Heavy Metal (Is The Law), which isn’t on the statute books even in Germany).

“Walls Of Jericho was just raw power - getting everything out,” says Kai. “But we wanted to step into something new.”

“We admired hard rock bands and progressive bands,” adds Weiki. “We were saying, ‘Let’s be more melodic, let’s be more progressive.’ We wanted to do more commercial stuff.”

Their ambitions were facilitated by Kai’s decision to step back from vocal duties. His replacement was Michael Kiske, an 18-year-old hotshot with a voice like Bruce Dickinson’s and the cockiness to match. With Kiske in place, Helloween were ready to make their great leap forward.

“What we were doing was well beyond Walls Of Jericho,” says Kai. “We realised, ‘Oh shit, this is kind of massive.’”

Helloween’s second and third albums, Keeper Of The Seven Keys: Part I and Keeper Of The Seven Keys: Part II, were indeed massive. So massive, in fact, that they initially wanted to release it as a double album. At least until their record label, Noise Records, pointed out that it was a dumb idea.

“They were like, ‘Are you stupid? If we split it into two albums, it will make more money,’” says Kai. “Not that we ever benefitted from it.”

Instead, Keeper Of The Seven Keys: Part I was released in May 1987, with Part II following 15 months later. Each album shifted between the epic and the emotional, the galloping and the goofy. Suddenly, Helloween were being talked about as the heirs to Iron Maiden.

“We chewed heavy metal down and spat it out our own way,” says Kai. “Someone came up with the idea to call it ‘power metal’. I mean, what the hell is that? I always thought power metal is fucking cheesy. And we are not cheesy, fuck that.” He grins. “Well, maybe we can be sometimes be a little bit cheesy.”

Behind the scenes, though, things were beginning to fracture. Camps were forming. Michael Weikath and Michael Kiske wanted to broaden Helloween’s sound to take in everything from Beatles-y pop and Elvis Presley-inspired rock’n’roll to acoustic ballads. The other three were having none of it.

“We wanted to rock,” says Kai. The latter was rapidly tiring of life in Helloween anyway. Touring was relentless and the band were getting little financial support from the label. To make things worse, Kai was hospitalised for two months in 1988 after contracting Hepatitis B (“How? A girl. One of them,” he says sheepishly). He asked for the band’s touring schedule to be dialled back, but, he says, the rest of the band ignored him.

He’d made his growing disillusion clear in the song I Want Out from Keeper…: Part II: ‘I want out / To do things on my own / I want out / To live my life and to be free.’ The voice may have been Michael Kiske’s, but the sentiment was Kai Hansen’s. Today, he denies I Want Out was written as a resignation letter, but that’s what it proved to be. In January 1989, the guitarist left the band he had founded half a decade earlier.

“He said he had to do what he had to do,” says Weiki now. “I said, ‘It’s nice of you to tell me, but just get fucking lost.’”

Weiki wasted no time in drafting in an old friend, Roland Grapow, as Kai’s replacement. Recording an album wouldn’t be so easy. Helloween had left Noise for EMI following the second Keeper album, but their former label launched a lawsuit that kept them tied up for the best part of three years. They could have regained the momentum they once had if they’d returned with a killer album, but 1991’s Pink Bubbles Go Ape was a dud. Worse was to come.

The once-strong musical alliance between Weiki and Michael Kiske was crumbling. The former hated the songs the singer brought in for their next album. Kiske refused to sing on the songs the guitarist was writing. The situation wasn’t helped by drummer Ingo Schwichtenberg’s increasingly erratic behaviour, which led to him being fired from the band in 1993 (he was diagnosed with schizophrenia and tragically died by suicide in 1995).

They eventually made an album, 1993’s Chameleon, but it was a sharp left turn that largely ditched their signature sound in favour of horn-propelled, pop-rock, singer-songwriter-style ballads. Fans hated it.

“We played venues that were a quarter sold out,” says Weiki of the subsequent tour. “It was pretty awkward.”

Chameleon marked the end of an era for Helloween. Michael Kiske left soon afterwards, the relationship between him and Weiki seemingly broken beyond repair. The band were two key men down and in debt to the equivalent of £800,000. No one would have blamed Michael Weikath for calling it a day. Instead, he decided to start over.

It was December 28, 1993 when Andi Deris got a phone call from his old friend Michael Weikath asking if he fancied joining Helloween.

“He told me he didn’t want to carry on with Michael Kiske,” Andi says, puffing on a monster-sized cigar as he sits in the sun outside his house in Tenerife, with the air of a man who isn’t troubled by much. “He said he’d rather split up the band.”

Andi was up for the job, not least because he’d just split from his own band, Pink Cream 69. “It was a big experiment to see if we could get this sinking ship floating again,” he says of the post-Hansen, post-Kiske Helloween. “There was a lot of pressure. So much pressure, in fact, that you actually forget about the pressure.”

To the relief of the fans, the first album Andi made with Helloween, 1994’s Master Of The Rings, was a return to core values. It didn’t make up the ground they’d lost, but it was the sound of a band climbing out of the hole they’d dug for themselves. Dogged perseverance and a run of albums that doubled down on their signature sound kept Helloween in the game throughout the second half of the 1990s and into the 2000s. Weiki claims there were no big-money offers for the classic line-up to reunite, which scarcely seems believable.

“No one said that,” he insists. “People weren’t interested in this flailing band Helloween.”

‘Flailing’ isn’t strictly accurate. The likes of 1996’s The Time Of The Oath, 2000’s The Dark Ride and 2005’s ‘threequel’ Keeper Of The Seven Keys: The Legacy kept Helloween in the charts in Germany and Japan, if not the UK and US. But a reunion of the band’s classic late 80s line-up could have kicked things up a level. And no one was more aware of that than Kai Hansen.

“I always thought we would be so stupid if we didn’t take the chance to reunite in some way,” says the guitarist. “Fuck all the bullshit when we were younger, let’s just celebrate what we did, even if it’s just a tour.”

Any acrimony surrounding Kai’s departure had long since dissipated. His post-Helloween outfit, Gamma Ray, had even supported his former group on tour, with the guitarist joining his old bandmates onstage. He’d also stayed friendly with Michael Kiske, collaborating with the singer on some of the latter’s solo projects over the years.

But there was still the bad blood between Kiske and Weiki to contend with – something the interim period had done little to dilute. When Helloween found themselves booked on the same festival bill as Kiske, it was suggested to Weiki that he may want to meet with his former bandmate to hash things out.

“I was kind of nervous,” says Weiki. “I had a Jackie Daniel’s in one hand, another Jackie Daniel’s in the other with the bottle and a cigarette, and another cigarette in my mouth.”

By the time the drinks had been downed and the cigarettes smoked, the two men had put their differences aside. “He forgave me,” says Weiki without irony or rancour.

But there was another, equally sizable stumbling block in the way of a reunion: Helloween themselves. The Andi Deris-fronted incarnation were doing well. Why would they risk everything they’d rebuilt for a one-off cash-grab reunion that might not even work out? Andi himself takes credit for coming up with the solution to that one.

“We were having a meeting with our record company in Tokyo, and someone said, ‘Well, what can we do to attract more attention?’” says the singer. “I said, ‘Bring Michael Kiske back into the band.’ There was 50 seconds of silence and then our manager said, ‘That’s actually a pretty cool idea. We’d have to bring the little one [Kai] back too.’”

And so, after several months of tentative emails, cautious Skype calls and face-to-face meetings, the current line-up of Helloween were rejoined by two former members. In 2017, they embarked on their first tour in this hybrid new/old configuration under the banner of Pumpkins United.

“We said, ‘Let’s do the tour and decide if we carry on or the calamity is so big that we cannot work together,’” says Kai. “But it went so well. At least, nobody killed each other.”

In the eight years since the tour, there have been two new studio albums, neither of which resulted in homicide. 2021’s self-titled Helloween had flashes of greatness, though it sounded like the product of a band who were still trying to fathom how to work together in the studio.

“There are a lot of fancy characters in the band, and there was some arguing about things on that record,” says Kai.

Giants & Monsters is another matter. Like its predecessor, it forgoes the easy nostalgia of recreating the Keepers-era sound. Instead, songs such as seven-minute pocket epic Giants On The Run and towering pop-metal anthem This Is Tokyo present this incarnation of Helloween as a 21st-century band. No less surprising is the unexpected and very genuine bromance between Andi Deris and Michael Kiske.

“I was super-sceptical and he was super-sceptical, but he came here to Tenerife and we spent three weeks hanging out,” says Andi of the beginning of their friendship. “And that was it. It was like meeting your soul brother. I thought, ‘Oh fuck, I wish I’d got to know him years ago.’”

The Helloween of today have come a long way from the Helloween of the late 80s, but in other ways they haven’t come very far at all. Uniquely, they exist as a legacy band and a contemporary one at the same time. Or, as Michael Weikath, a man with a uniquely skewed sense of humour, puts it: “I guess we never sucked enough that people wanted us to go away and never come back.

Giants & Monsters is out now via Reigning Phoenix. Helloween play London's Eventim Apollo on October 20. For the full list of upcoming tour dates, visit their official website.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.