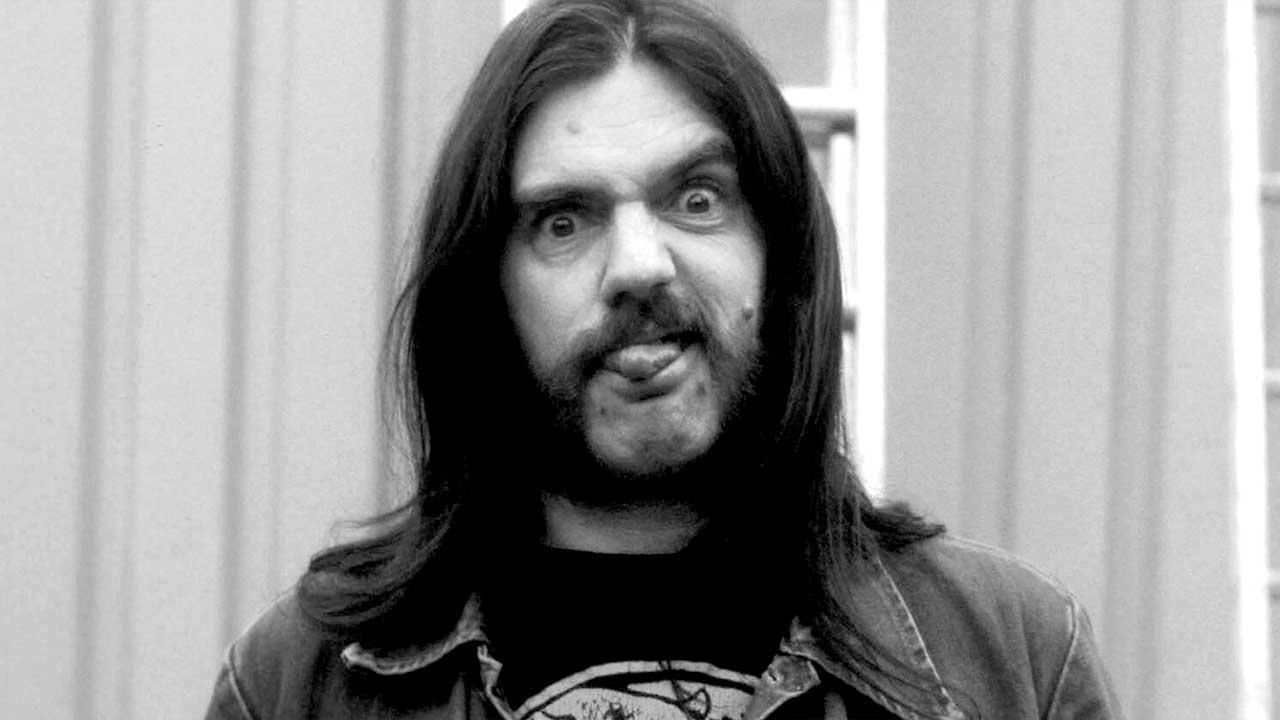

Motörhead's Lemmy Kilmister: A day in the life of a legend

In 1979, Motörhead’s career began to take off in style. Legendary journalist Malcolm Dome recalled the effect it all had on their talismanic frontman

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Lemmy Kilmister is not in a good mood. It’s December 1979 and I’m in the offices of Greybray, Motörhead’s management. I’ve just told the man that I’m reviewing the On Parole album for weekly music magazine Record Mirror. This was the first album the band recorded in 1975, but it was shelved by their then-label United Artists, and was only just about to come out – finally.

“So, what? Why should I care if you’re reviewing it?” snaps Lemmy, adding a hard stare. He realises that maybe he’s being a little harsh, so offers:

“Listen, United Artists hated what we recorded, decided not to release the album, dropped Motörhead, and forgot about us. Now, because we’ve had a little success they’re trying to make money on the back of that. They didn’t even tell me it was coming out!”

Lemmy is coming to terms with the reality that the band are now getting people’s attention. The fact that both Overkill and Bomber had made the Top 30 in the UK album charts highlighted that the trio had commercial potential, and the title tracks from each album had been Top 40 singles. Motörhead even appeared on Top Of The Pops, which amused Lemmy.

“I got the idea for Bomber from a novel I read, called Bomber [by Len Deighton]. It’s about a bombing raid over Germany during World War II. And we got to play it on Top Of The Pops,” he says.

“We’d done it before for Overkill and Louie Louie, but they didn’t much like having us on. We don’t fit in with the sort of tame, inoffensive musicians they’re used to having. But I love the fact the audience don’t know how to react to us. You can see them getting confused at the front! Ha ha!”

I wish we'd told the label to fuck off

Lemmy

It had been something of a landmark year for Motörhead. They had begun it having just signed to Bronze Records, but if anyone was under the illusion that the bassist/vocalist was in a positive frame of mind about things, then he quickly dispelled this one night in January at renowned London after-hours rock bar, Frank’s Funny Farm.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

This writer witnessed someone asking Lemmy how the recording for the new album, which would be Overkill, was progressing. The response?

“How should I fucking know? You can never tell what anything sounds like until it’s finished. What a daft question!”

Lemmy wasn’t angry. He just wasn’t prepared to indulge anyone. This person was interrupting his social activities, and that was unforgivable. It was also typical of his forthright manner.

AC/DC frontman Bon Scott told me later that year: “I like Lemmy, because he’s straightforward. He shakes your hand, looks you in the eye and tells you what’s on his mind. I’m sure we’d work well together. There’d be the occasional punch-up, but then we’d go to the bar, have a few and all would be forgotten.”

Overkill was released in March ’79, and it was immediately obvious that the band had stepped up to another level compared to their self-titled debut, which had come out two years earlier through the Chiswick label.

It reached No.24 in the UK chart and got a positive reaction all round. Finally, there was cohesion and purpose to what the threesome were doing.

The band had already played six of these songs at the end of 1978 on their Beyond The Threshold Of Pain tour, and on March 23, 1979, they went on a 20-date headlining British tour, performing at various times no fewer than nine tracks from the album. The only song not in the set was I’ll Be Your Sister. Motörhead ended this part of the tour with a show at The Paris Theatre in London on May 26, recorded by the BBC.

Following the success of Overkill, Bronze demanded another album, and Lemmy was soon back in the studio working on what would become Bomber. He later felt that it suffered from being rushed, and although producer Jimmy Miller was a superstar who’d co-produced Overkill and worked with the Stones, he was known for having a heroin problem. While Lemmy was never a stranger to drugs, he took music very seriously and demanded total commitment to Motörhead.

“We did things differently with Bomber,” said Lemmy in 1979. “Usually, we get the chance to perform songs live before going into the studio to record. But for some reason we didn’t do it this time. Maybe it’s because we were being hassled by Bronze to get another album done fast, as Overkill had done well.

“I wish we’d told the label to fuck off and leave us alone. If you listen to Bomber, the songs don’t have the edge they have when we do them live. For me, the production is a bit too smooth.

"I can’t say it’s an album I am happy with. The songs are all good, but Jimmy Miller… well, we made the mistake of letting him do what he wanted without arguing. Sure, Bomber sold well. But I doubt we’ll work with Jimmy again. He has his own demons to deal with, and it made him difficult and unreliable.”

Bomber came out on October 27, just seven months after Overkill, and did even better as it peaked at No.12 in the British chart. It was favourably received, but many believed it wasn’t as good as its predecessor.

Still, it did further mark out the band as being different to the likes of Judas Priest, Black Sabbath and Rush who were in the ascendant at the time. Motörhead possessed a refreshing honesty and energy, and seemed to be more in step with the likes of Saxon and Iron Maiden, who were emerging as NWOBHM began to bloom. Like AC/DC, they were down to earth and had a streetwise groove that appealed to the new generation of metalheads.

They did a 30-date UK tour, with the famous 40-foot Bomber as a big attraction, and performed six songs from the new album.

Lemmy was always determined that people shouldn’t see Motörhead as being involved with any trend of the period.

“I don’t feel we’re part of any movement,” he said. “Some people have called us punks and others refer to us as being a heavy metal band. But I just think what we do is rock’n’roll, nothing else. When you listen to Bomber, does it sound to you like punk or heavy metal?

"The thing is that we attract lots of different types of fans. Come to a Motörhead gig and you’ll see long hairs and short hairs all mingling. I like to think we appeal to those who like proper music, with no gimmicks. That’s what the three of us do – we work fucking hard at making this band as good as it can be.”

We're loud and rowdy but we can play. This is a serious band.

Lemmy

Despite Lemmy’s claims of harmony between the fans, there were problems at the Reading festival when Motörhead appeared on August 24, 1979. Sporadic fighting broke out between the band’s fans and those of punks Punishment Of Luxury, but that has always been put down to boredom rather than genuine animosity.

Incidentally, Lemmy et al were third on the bill, behind The Tourists and The Police, and following The Cure and Wilko Johnson. However, there was no doubt which band got the biggest reception of the day – Motörhead!

Nobody had ever given the trio any handouts. They’d worked hard and fought for everything they’d achieved. Their debut show was opening for progressive band Greenslade at The Roundhouse in London on July 20, 1975, and the following March, on the band’s first headlining tour of the UK, they were playing small venues like The Music Machine in London and Tiffany’s in Bristol. By the end of 1979, Motörhead were headlining bigger venues such as the famed Hammersmith Odeon, where they did two sold-out nights.

“When we first started, someone said we were the worst band in the world. Now, I like to believe we are so much better at being that ‘bad’. If you want pretty boys playing inoffensive music, go listen to The Police. We’re loud and rowdy, it’s the only way we know how to be.

"But we are also very good at playing our instruments. Just because we have our amps turned right up doesn’t mean we’re trying to hide our lack of talent behind a wall of noise. We can definitely play. This is a serious band.”

One of the main motivations that drove Lemmy on during this period was his determination to prove people wrong. “I want to shove our music in the faces of all those muthafuckers who said we were a waste of time. Is that me being vindictive? Yes, it is. But I’m fed up with know-nothing music industry arseholes who think they know what good music is. They’re the sort who’d have told Little Richard he was wasting his time when he first started.”

He also got irked when it was assumed he was rich, because the band had

two charting albums and a couple of singles that had sold well in 1979. It’s passed into legend that Ian Kilmister got his nickname of ‘Lemmy’ from

a habit of borrowing money, and I got to witness first-hand the man in action.

In June 1979, I was in his manager Doug Smith’s office, when Lemmy politely knocked on the door.

“Sorry to interrupt, gentleman, but could you lemme have a fiver, please?” Doug handed over the requisite note, only for the man to add with a glint in his eye, “Actually, can you make it a tenner?” The extra cash changed hands. With that, he left and Doug said, “Now you know why we call him Lemmy!”

He always attracted a crowd, and it was interesting to watch one night at London’s Music Machine [now Koko] when he bought a round for several people, then told them quite reasonably that he expected them to reciprocate, and he didn’t just drink Jack Daniel’s and Coke – these were doubles, or triples!

“I’m always happy to get anyone a drink,” he said as an aside to a couple of us that night, which was October 16, when NWOBHM band Samson were playing. “But everyone assumes I’m some rich pop star now. That’s not how it works. I have a little cash, but I’m not exactly Mick Jagger.”

The Lemmy of 1979 was no different to the way he was in subsequent years. Articulate, honest and focused, he could as easily be lonely in a crowd as the centre of attention. But he was at his best with real fans.

That was underlined in late 1979 when Motörhead, around the period when Bomber was released, made an appearance at The Bandwagon Heavy Metal Soundhouse in north-west London, at the time one of the most important and influential rock clubs in the country.

Lemmy revelled in being among those who adored the band for the right reason – they loved the music. There was no pretension, no attitude. As far as he was concerned, this was a meeting between likeminded people, all devoted to the glory of music.

“This is what it’s all about,” he said. “Everyone’s just out to have a good time, and that’s what I’m all about as well. If we can put smiles on faces, we’ve done our job.”

Motörhead 1979, a deluxe set of Overkill and Bomber, is out October 25 via BMG. Both come as hardbound bookpacks in 2CD and 3LP format, with previously unheard concerts and interviews, and photos.

Pre-order Motörhead 1979 Double Vinyl Deluxe boxset of Overkill and Bomber

Overkill and Bomber reissued as hardbound bookpacks on 2CD and 3LP, featuring previously unreleased concerts from the time and a collection of rare photos.

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.