Lucifer, Isaac Asimov and Ringo Starr: the story behind Deep Purple's The Mule

A showcase for the talent of Ian Paice, The Mule became the benchmark for 70s rock drumming. Today it’s best known for its solo on Purple’s Made In Japan live album

The internet is a perilous place. It’s a mine of misinformation, non-facts, rumour, innuendo… and outright lies. Case in point: Deep Purple’s The Mule, a song that originally appeared on the Fireball album in 1971.

As with the majority of compositions by the Mk II Purple line-up, The Mule is credited equally to the classic quintet of Ritchie Blackmore, Ian Gillan, Jon Lord, Roger Glover and Ian Paice. But hang on a minute. Type the track title into Google, or indeed any search engine, and a sixth name pops up: that of Jethro Tull mainman Ian Anderson.

Drummer Paice chuckles down the phone from his country mansion in Henley-on-Thames. “I can state categorically that no Aqualung influences were involved in the making of The Mule. It just so happens that Anderson is my middle name – Ian Anderson Paice.”

Somewhere in a parallel universe there’s a live rendition of The Mule with a marathon flute solo. But what happened in reality was this… After its appearance on Fireball, The Mule was incorporated into Purple’s stage show and became the focus for Paice’s tub-thumping talents. Live, the song’s running time increased dramatically. The Fireball version lasts 5:21; on the 1972 live album Made In Japan it’s twice as long.

The talent exhibited by Paice on The Mule sent shockwaves through the 70s rock scene. Cream fans in particular were stunned by the Purple pounder’s dextrous display of controlled power and awesome technique. Ginger Baker’s Toad – previously the benchmark for such drum-solo shenanigans – was summarily squashed under the trampling hooves of The Mule.

“I used to pick vehicles for drum solos basically rhythmically,” Paice states. “If I had a rhythm that gave me a good leadoff point to go into a solo, then that made it much easier. The Mule was almost written with a drum solo in mind. But obviously until you get it on stage you never really know if it’s going to work.”

Besides its chiming Blackmore riff, The Mule contains an atypical repetitive drum pattern inspired by the playing of Ringo Starr. Indeed such is the precision and consistency of Paice’s percussive refrain that it could almost be on a tape loop.

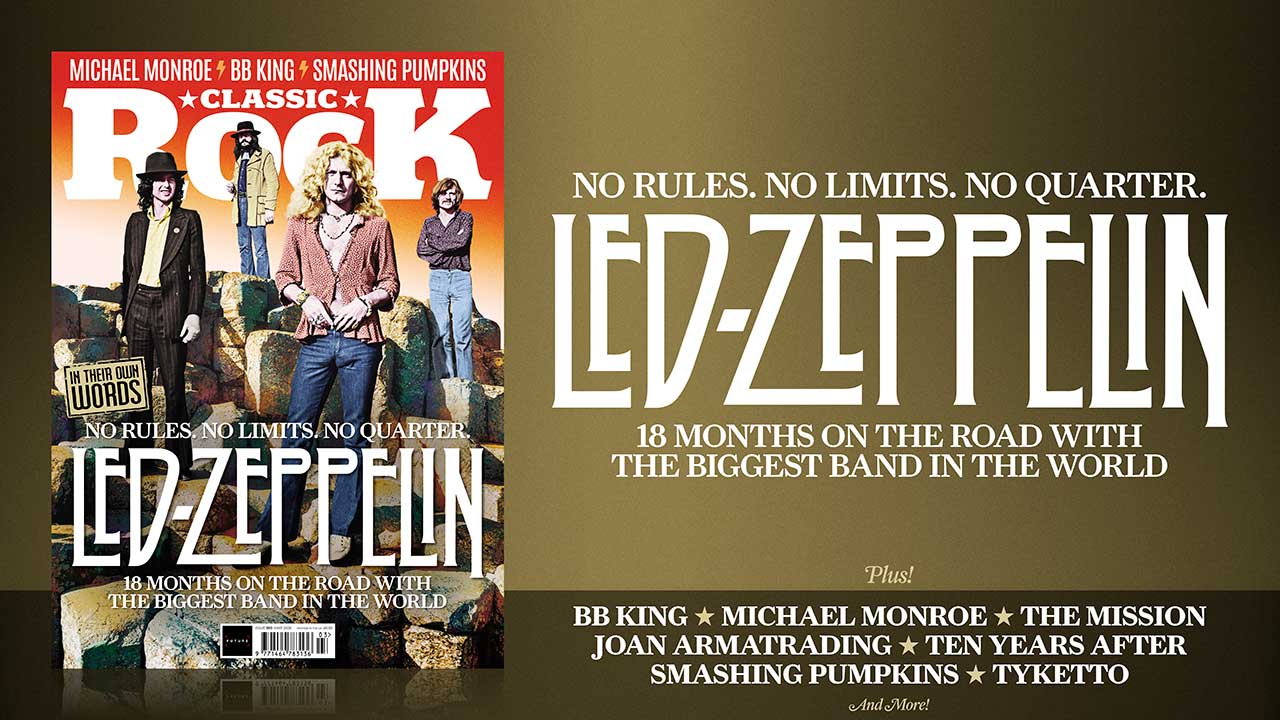

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“The idea came from Tomorrow Never Knows [from The Beatles’ Revolver album],” Paice reveals. “Ringo plays wonderfully, but his pattern is much darker and more eerie than mine. I just took the rhythmic emphasis and played it in a slightly more violent way. I’m a big fan of Ringo. He’s one of the great unsung rock’n’roll hero drummers – and not just because he’s a Buddy Rich type, like me. Every song Ringo plays on just feels great. From the early Cavern stuff to his more complicated work on Abbey Road, every track is brilliant. And that’s not luck, that’s pure talent – the knowledge of why it should be a certain way.”

If you’re a sci-fi fanatic you’ll know that The Mule is an evil galaxy-conquering character in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series of books. Frontman Ian Gillan has admitted that the lyrics to Purple’s same-named song were “inspired by Asimov… He was required reading in the 60s and 70s”. On stage Gillan would often preface The Mule with the comment: “This song is all about Lucifer and some of his friends.”

Paice, however, has a interesting take on The Mule’s opening lyrics: ‘No one sees the things you do/Because I stand in front of you/ But you drive me all the time.’ “It’s all about me,” he insists. “I’m behind Ian on stage, I’m spurring him on with my playing. It’s a very nice, subtle little lyric. It escaped me for decades. Asimov may well have inspired Ian but, looking at those lyrics, I can personalise them. I never thought about it until two or three years ago. One night the vocals were particularly loud on stage and I thought: ‘Hang on, there’s something I’ve never noticed before.’”

Purple wrote and recorded Fireball at several locations, including De Lane Lea and Olympic studios in London, and The Hermitage in Welcombe, North Devon, between September 1970 and June 1971. “The Mule would’ve come from a jam or designated afternoon writing session, because we were still using rehearsal rooms in those days,” Paice states.

Committing The Mule to tape was not without problems, though. “In those days we used eight-track tape,” Paice recalls. “Sometimes to get different effects you’d put the tape on the machine upside down, to be able to record backwards. It’s a technique The Beatles often used. You’d have sounds fading in and out, and you could achieve some wonderful effects.

“Halfway through The Mule, our engineer flipped the tape. But instead of going on to one of the clear tracks, he accidentally erased the drums. The kit I’d been using for recording had been packed up and sent on a truck to Europe, so we had to go back in the next day with another set of drums. Because they were different, they didn’t sound exactly the same, no matter how carefully we tuned them. So when you play The Mule, you get to the halfway point and the drum sound changes significantly.”

Paice’s solos began cropping up in different songs when Purple eventually dropped The Mule from their live show. “We used to put one in Speed King and a couple of other tracks where the rhythm lent itself to a good start-off and I could just flap around until I ran out of ideas and then hopefully bring the rest of the band in.”

Today The Mule has been reinstated into Purple’s live performances. “We brought it back because a lot of people wanted it. It’s much curtailed, though – the drum solo is only two or three minutes long. But in this day and age that’s probably enough."

Deep Purple were the cover stars of the August 2020 issue of Classic Rock magazine, which is still available to buy.

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.