"And then things got weird..." Johnny Depp on how music saved his life

Back in 2016, Johnny Depp spoke to us about how music got him through an abusive childhood, why he has no memories of puberty, and why we should all take more risks

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

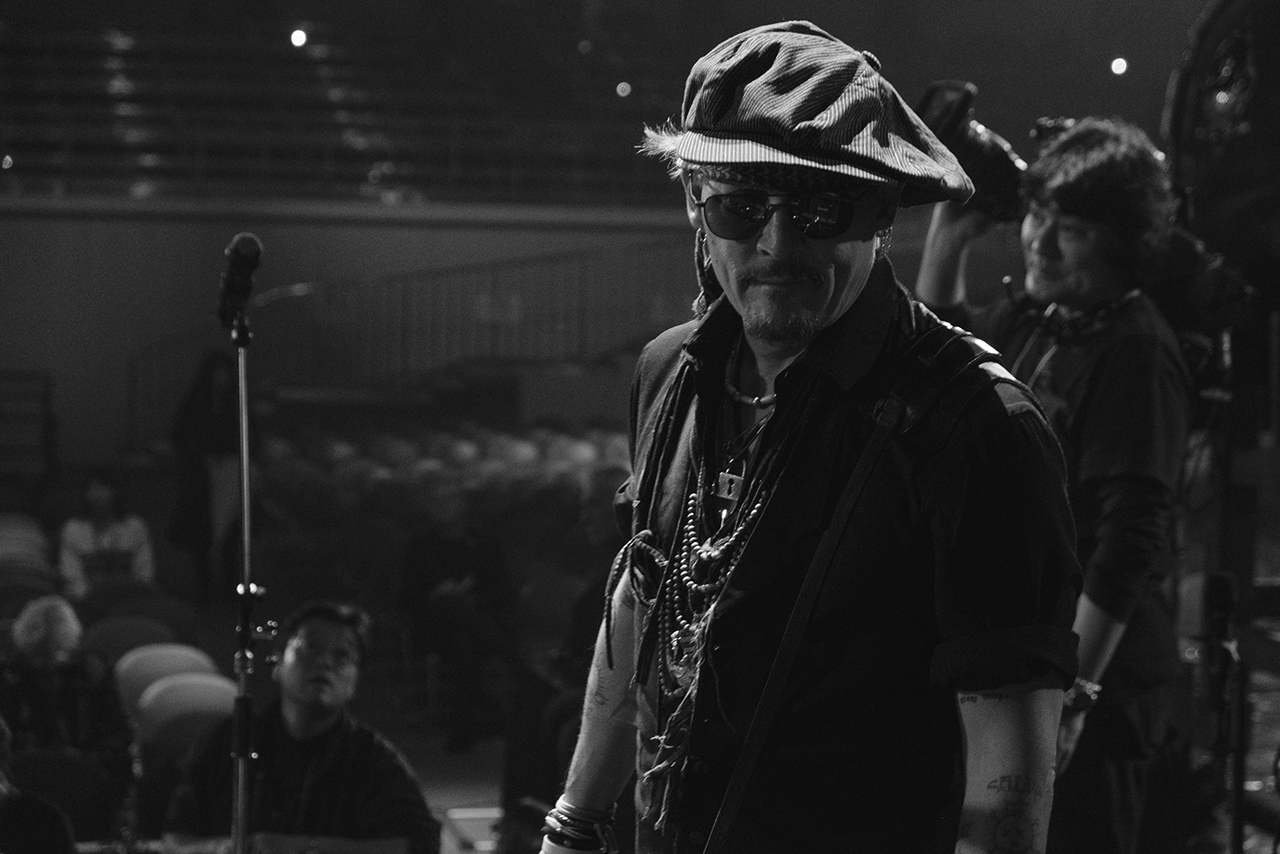

Johnny Depp is in his dressing room in the Ryogoku Kokugikan, Tokyo’s national Sumo arena, on the afternoon of the Classic Rock Awards, 11th November 2016, sipping a glass of red wine and rolling cigarettes (Golden Virginia tobacco, liquorice skins).

At 53, he could pass for a decade younger, although maybe his tattoos, jewellery and tastes would give him away. The Daily Mail later run a story about the awards and the article is all about what Johnny’s wearing (“Leather Overload: Johnny Depp and Joe Perry work the edgy look at the Classic Rock Awards in Tokyo”). But he’s not in costume – this is how he dresses. When he gets new clothes, he says, he’ll rip them, smash them with hammers, burn holes in them with cigarettes, anything to customise them to his own look. He has a similar approach to movies and music.

Depp is here, not as an actor or celebrity, but as part of the house band – Robert and Dean DeLeo of Stone Temple Pilots, Korn drummer Ray Luzier, and fellow Hollywood Vampires Tommy Henriksen and Joe Perry – who will play on the night with members of Cheap Trick, Scorpions, Def Leppard, Tesla, Megadeth and, finally, Jeff Beck, who is presented with the Icon award by Jimmy Page.

Article continues belowDepp has been a music nut since he was 12. He gigged throughout his teenage years, mostly in a Florida band called The Kids, but also including a spell in Rock City Angels, who were later signed to Geffen.

But as his acting career took off, music became something he dabbled in – playing on an Oasis record, recording with Shane MacGowan, forming the band P with Butthole Surfer Gibby Haynes – until he was finally coaxed back up onstage by Alice Cooper and formed the Hollywood Vampires with Alice, Johnny, Joe Perry and Tommy Henriksen at its core.

It's November 2016. Earlier in the year, Amber Heard filed for divorce from Depp, with claims that he physically abused her during their marriage by throwing a phone at her. By August, they have reached a settlement and released a joint statement: "Our relationship was intensely passionate and at times volatile," it says, "but always bound by love. Neither party has made false accusations for financial gain."

In 2016, it just seems like another ugly celebrity split. But there is nervousness in the camp. We are counselled not to ask him about his marriage during our interview and there are rumours that certain A-Listers might not want to be seen with him, that maybe it's not a 'good look' to be photographed with Johnny Depp right now.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In the end, it doesn't work out that way at all. No-one is awkward around him. It's just another ugly celebrity split. None of our business. It'll all blow over.

Q: When you met Jimmy Page yesterday, it looked like it really meant something to you.

Johnny Depp: Well, he does. Did heavily and still does. The guitar players for me early on were Keith Richards, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and Joe Perry. There was something about them, some mystique to them.

When did you become a guitar player?

I was about 12 years old in the backseat and we were driving down the sort of main boulevard in this little town we lived, and there was a little local concert going on in the parking lot of the grocery store. We got stuck at a stop light and there was a band playing. I remember the name of the band, actually, they were called Rocklin Channel. I ended up playing with a couple of the guys in later years, you know.

Is this Florida?

This is Florida. I heard them doing [Aerosmith’s] Dream On you know, and I thought, fucking hell, that sounds really good, and how fucking cool to just pick up a guitar and just blast, you know? So I talked my mom into buying a shitty little Decca guitar for 25 bucks, and some little blue Plush amp that sounded like- it was just trash, it was fantastic. Stole a Mel Bay chord book out of a department store – the blue Mel Bay chord book with the black and white pictures y’know? So I figured out where to put my fingers, figured out chords and started to listen to records, lifting up the needle and pulling it back to the top of the solo, over and over…

So you’re self-taught?

I had a guitar class at school. I dropped out but the guitar class was the only class I would’ve passed. I don’t know why, but I just knew that school wouldn’t afford me anything. I knew that I wasn’t going to be working for an insurance firm. What was I, 15 when I dropped out? It’s like, ‘I gotta fucking be an adult now’. There was a part of me that was gonna just join the Marine Corps and say 'fuck it' and get out, but I started playing clubs when I was 13. I’d sneak in the back door, play a set and split – stand out back, smoke, go back in to the set. I played under-age up and down the East Coast, for a couple of years.

Making money?

Nah, no, no, all my money died with the bar tab. It’s the classic cliché, you know. It’s always going to be the bar tab that gets you. In those days.

So this is the mid 70s?

Yeah. I was born in ’63 so I was 12 in ’75. I found a way to escape all the, sort of, nightmare home stuff, you know? It was a pretty radical – a pretty unpredictable – household that I lived in. You never knew what was going to be coming next. It might be an ashtray thrown at your head. Or a shoe…

By your father?

No, mostly my mom. My dad was good with the belt. But those were different days. They did what they knew best. But when I found guitar, from that moment on, like, I don’t have any memory whatsoever of puberty. None. Because I just literally locked myself in my bedroom and paid attention to the records, and I learned stuff.

They say that nothing ever sounds better than the music you love when you’re 14.

Yeah. That’s why music is so important. It’s an instant sort of experience of time travel, y'know? A certain emotion will arrive with various songs that you experienced as a kid. Smokey Robinson comes on and I remember where I was. I was always fascinated with these amazing crooners. Like, Barry White. I mean, you don’t necessarily think of him as a crooner, but the guy – what he put he down and what he created… They were making really cool records back then. Because that was sort of the beginning of a whole lot of bad rock and roll.

Right. Who are you thinking of?

There was this transition. You had the early 70s where it was Alice, Aerosmith, erm-

David Bowie, Lou Reed…

Exactly, and then around ’75 to ’77 it was kind of Saturday Night Fever.

And you had prog rock. Yes, Genesis…

Rush, Triumph and all these- [makes face].

Not your thing?

No. And it was the first experience that I had of what I call the ‘oh look at me’ guitar player. Who tries to fit in as many notes as he can. [Singing the words like they’re guitar hammer-ons] ‘Look at me, look at me, look at me, look at me, look at me, look at me’. I’ve always been like, ‘That guy just went all over the neck and so I’m going to hit, like, three notes, see if I can make that work'. I was never one of those guys. Edward Van Halen was impressive when he first came out. I thought, ‘Well this guy’s right up there, he’s invented a new style’. And I could play it a bit but then I realised that it became a trap, like ‘It’s what I’m known for, so I’ll do it.’ I hated that. The idea that they’re expecting me to do it.

You were playing a yellow Les Paul Junior, yesterday. Johnny Thunders played those. Is that why you’ve got it?

I always liked the TV Yellow. It probably was Johnny Thunders, you know. It was a fucking weirdly under-used guitar.

Were you a New York Dolls or a Heartbreakers fan?

I loved The Dolls. I had already had my Iggy fix, you know. I had my Patti Smith fix. I had my – at a certain point – Ramones fix, The Clash and all that, you know? But Johnny- I got to meet him one time. I leaving a rehearsal studio with this old band and he was coming in to rehearse right after us, and he was with this dude that I knew, who was capable of supplying things. So yeah, we stood out in the parking lot and talked for a little while. He was a little guy. Really tiny little fragile guy, but he wrote such beautiful songs. I mean, Chinese Rocks but also You Can’t Put Your Arm Around A Memory.

Also what David Johansen was doing at the time. He did a record [In Style, 1979] and it has that track Flamingo Road on it, where I think it’s about his experience of losing his wife to Steven Tyler, and the words are beautifully written, beautifully executed. The whole record’s great. Johansen was doing some great shit back then too, you know.

I met Johansen when I was 15 because a friend of mine knew him. And Blondie Chaplin, the guitar player. And weirdly Blondie and I are still in touch. I mean, I met the fucker when I was 15, that’s almost 40 fucking years ago or something.

[My phone rings and I’m using it to record the interview.]

I use my phone for that [recording]. It’s a saviour when a lick or something comes into your skull and you know you’ll fucking forget it any second now. I just grab the guitar and record on there.

So you’re always writing songs?

Yeah, I’ve always written stuff. Early on, I never thought my words fit with the music. I just fucking hated the idea of doing love songs and shit like that, or at least love songs where, you know, they begged for sympathy and all that shit. So I was fighting desperately against that kind of thing and I learned a lot, trying to stay away from other people’s formulas…

Well, that’s a tough job isn’t it? It’s much easier to follow than it is to carve out your own thing.

Yeah. I mean, it’s the same in the movies, you know. You read a script and you know you’ve got something good there. And then someone says, ‘Put this in some kind of shape’, you know. A thing that I don’t believe in which is called The Three-act Structure. That should be killed immediately.

Right. Guys like Robert McKee wrote books, basically outlining the formula for successful screen-writing, the hero’s journey and all that…

Everybody has sort of, you know, gobbled those up but I feel like you should fucking run as far away from formula as quickly as possible, do you know what I mean?

I do. My kids grew up watching Pirates Of The Caribbean and it was a delight watching them for this very reason. Jack Sparrow died in the second one, and the third one began with him dead, but in a surreal underworld, talking to himself, surrounded by crabs. It was daft and a bit dark. My kids weren’t confused by that – they loved it. You had no idea what was going to happen, but you were along for the ride…

That’s the thing that I was fucking sure of when we did Pirates. I mean, I knew Disney hated me, I knew that most of the actors hated me, I mean the writers definitely hated me because I’d re-written all their shit… But there’s a certain point when you know that character better than anyone, and you’ve got to be true to the character. And to the director’s vision – I mean, the vision of the film, certainly – but, again, why do anything if you don’t feel like you can actually add something to it?

The films that I’ve done I’ve felt like, yeah, maybe this hasn’t been done to death, maybe I can put something in here that’s different, that’s absurd, that they’re not expecting. And I guess I’ve approached music the same way, really. Or I probably approached acting that way because of music.

I don’t like the idea of anything being pat, you know, down perfect. If it becomes perfect, if everybody’s comfortable with their lines, then I sort of like the idea of dropping the bottom out of the scene. It’s like changing course in a jam session, you know, because that’s where you see the real honesty.

Then it’s unpredictable.

You know, you start throwing lines out there that nobody- They’re not cue lines, you know, nobody knows when to say their line, the bottom’s just dropped out – so bring it back. You give that responsibility to them, you know. It’s a similar thing to playing, I think.

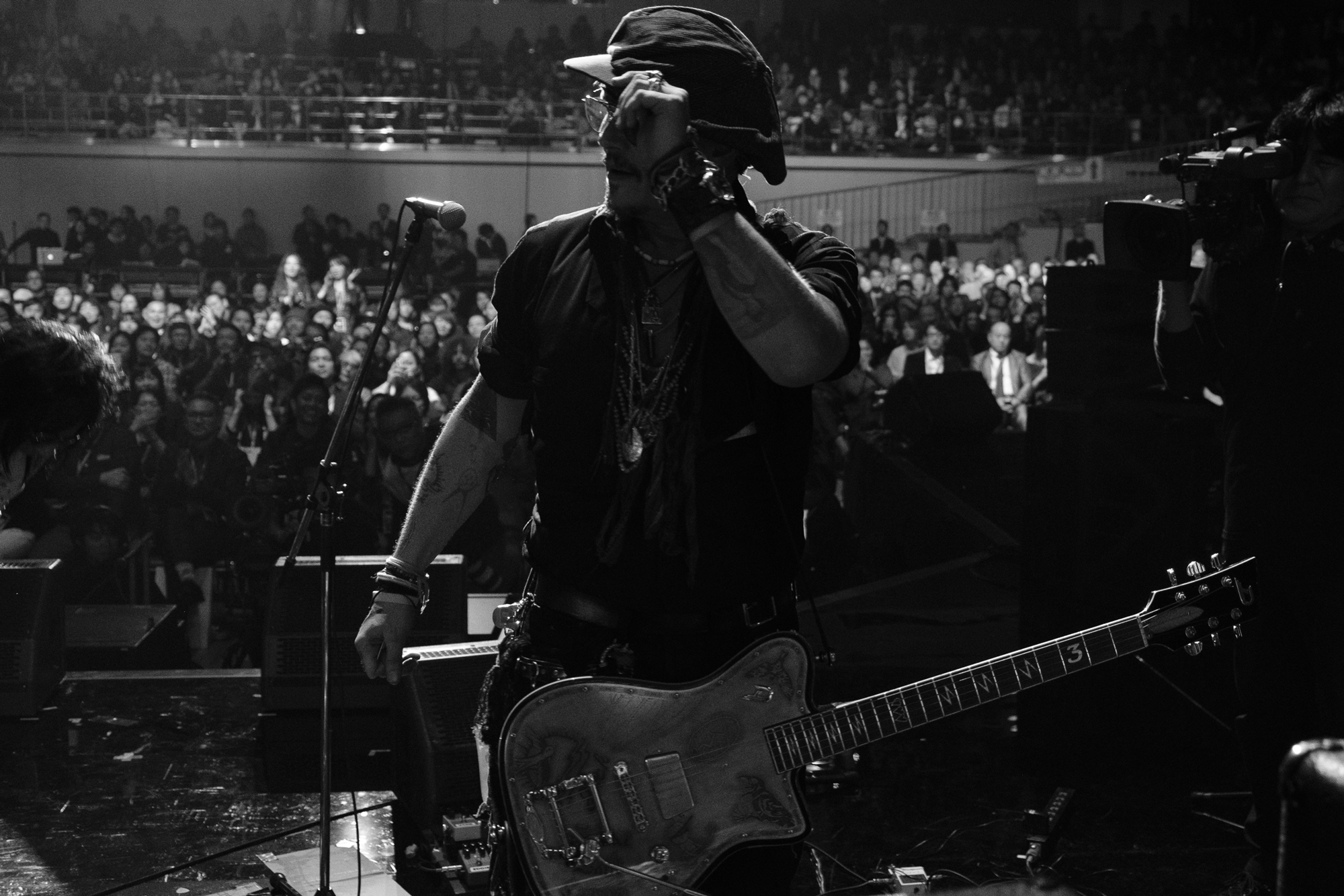

I was watching you play and rehearsing, and I was thinking-

“He’s very sloppy.” [Laughs]

No, not at all. But you were playing with your head down, and I thought: you’re the most famous face in the room and all eyes are on you. You don’t want to look up and catch everyone’s eye, so you get lost in the music. And it must be refreshing for you to be in a band and just be that: just one of the band.

That’s the thing you miss, you know. When I was a kid, fuck, I had to make dough and there were these movies that people would hire me for, y’know. It was like, ‘Yeah, I’ll take this so I can pay the rent’. All I was waiting for was the band to get back together. So I just kept doing these fucking movies until my band got back together – and they never got back together. So I figured at some point, like, ‘Oh alright. I guess you’re on this road now, you may as well, you know, figure out what the fuck you’re doing here man’, you know. Commit to something.

And then it started to get fun, you know. I guess what I love about my day job is the actual being in the trenches, you know, like that’s as close as it gets for me to performing on stage, because you’re in another world. It’s probably the one place that I can actually be me, y’know?

Tell me about the Hollywood Vampires.

Our first two shows were at The Roxy and then we did Rock in Rio to, like, a 100,000 people. So, I mean, even though I get lost in it and I’m not- I’m just playing. I got over the 100,000 people thing pretty quick. The further it goes back it there’s just silhouettes, it’s like wallpaper-

It was an amazing experience. I’ve done shows that I was really lucky to be involved in since I was 17 years old opening up for Iggy. I did two shows with Iggy at 17, and the Ramones. We did a lot of opening act stuff, you know, because it was a kind of a big fish in a little pond thing. So they always matched us up with whatever new wave band was coming up: Bow Wow Wow, The Lords of the New Church…

The show that we played with them, Stiv Bators walks in the room and he goes, he goes, ‘Hi fellas,’ in this really like sweet voice, like Iggy, you know. He said, ‘Whose Bassman head and Marshall 4x12 is that?’ I said, ‘That’s mine.’ He said, ‘Hey, would you mind if I played through that?’ I said, ‘No, you’re welcome to it, man.’ So Stiv played through my amp.

I remember we opened for The Pretenders and Ray Davies was standing on his head in the dressing room. So bizarre.

So this band was The Kids? Did you ever release anything?

We recorded stuff but we always had these producers that wanted to make everything really like syncopated and tight…

That wasn’t you?

No. Far too sloppy.

You were in the Rock City Angels who were later signed to Geffen.

Yeah, it was a weird thing from the beginning with the Rock City Angels. I’d written one or two songs with my buddy Mike Barnett who’s now gone on to other things in the universe – dirt and worms or something you know – Bobby Durango the singer, gone, dope. Big dope period that. But their first record for Geffen, I had to go off – I got hired to do the show 21 Jump Street, so I had to go to Canada, quit the band. They suddenly get this big old deal with Geffen and their first record was a double album, which I thought was a mistake.

It’s ambitious.

Yeah.

And ‘ambitious’ is not always a bad thing, but…

I don’t know [laughs], maybe a little more discretion with some of the tracks, you know? It’s like, there’s a lot of good music out there, man… You’ve got to have like 25 tracks, and pick out twelve or something.

It’s funny cos, again, just like my day job, you know, sometimes words look great on a page, but when they hit the air there’s something that’s just not right, they don’t work. You could spend eons just trying to figure out what the fuck it is that’s making it so wrong.

I did this film called The Libertine and I played John Wilmot, the second Earl of Rochester [an infamous bawdy poet, satirist and notorious rake of the late 1600s], and there was this huge, like, five pages of dialogue. It was his poetry and I couldn’t-, I’d done so much research on the guy, but for some reason I couldn’t fucking swallow this poetry. I couldn’t get it to stay in my mouth – I couldn’t get it to stay in my mind – and my friend said, ‘No, something’s wrong, I’ve never seen you do this.’ So I went back to the original material and they had edited his work.

So that it wasn’t in Old English, so that it was more modern?

With films like that there’s a lot of history, there’s a lot of exposition or whatever. I felt that his poems were so important to him that to fucking edit the guy’s work and, you know, try and slide three poems into one – that was why it wasn’t coming. It didn’t flow, you know. Then when I added his stuff, the real stuff, it came like gangbusters.

So when you’re playing music – though it’s not remembering lines or serving the scene, or serving the script or whatever – on stage, it’s the same sort of thing. You’re serving the song but, more, you’re serving the moment, you’re listening to the drummer and you want to fucking- You feel it coming and you want to, you know, hit that [mimics playing] BA-BA-BA with the snare, you want to be right on that…

And it’s risky isn’t it, you could fuck up.

You could fuck up horribly.

I guess in a movie you can re-do it, but at a gig…

Yeah, which I love. I think every actor should walk into a scene, you know, with the idea that this could fucking fail miserably. I think it’s important to take those risks. It should be scary. You know, you’ve got a fucking character that you’ve come up with and you believe in, and you feel a very strong foundation of this character beneath you. At that point, there’s really nobody who can enter that circle, and it’s the same thing on stage.

If you fucking hit a bad note man, stretch it, see where it’s gonna go. I love stretching notes you know, just to see where it’s going to go. If I feel like, ‘Fuck, I’m a half step down’, I’ll just bring it up a little bit more. It’s the same approach really you know, improvisation is always the best thing.

I think some of the best performances of any recording artist, especially the early recordings, it’s fucking chance. They had to rely on chance. You know, Robert Johnson would record in some hotel room in Texas and he would turn around and face the wall so he wouldn’t see how he played. Which also gave him, because he was probably four feet from the wall, it gave him a little bit of a slap, a slap echo.

I mean, the stuff he did in – what was it ’36, I guess? – and it didn’t really see the light of day until guys like Beck and Keith and Clapton started doing that shit. Can you imagine: like Howlin’ Wolf and Son House – those guys hadn’t been [discovered].

Muddy Waters: Keith and The Stones went to Chess Records, to visit the place, you know, and they walk in, and Keith says he sees a dude in a white suit painting the ceilings on ladders, painting the fucking ceiling, and it was Muddy Waters. He was changing light bulbs and painting. Keith’s like, ‘Goddamn Muddy,’ and he’s like, ‘Oh you them boys did my song, hey thank you man, thank you for that…’

I love those festival bills you see from the 60s with like, The Grateful Dead or Creedence and they’ve got Bo Diddley and Muddy Waters or Albert King, or someone on there, introducing their audience to all this great music they’d missed.

Go to YouTube, man, look at Bo Diddley Mona, it’s a performance on a television show, like a variety thing, I don’t know what the fuck it was, but I tell you, he’s so fucking cool and the chicks playing… These chicks are so sexy. It’s like, it’s just mind boggling because it’s so fucking primitive and so [mimics’ beat of song]…

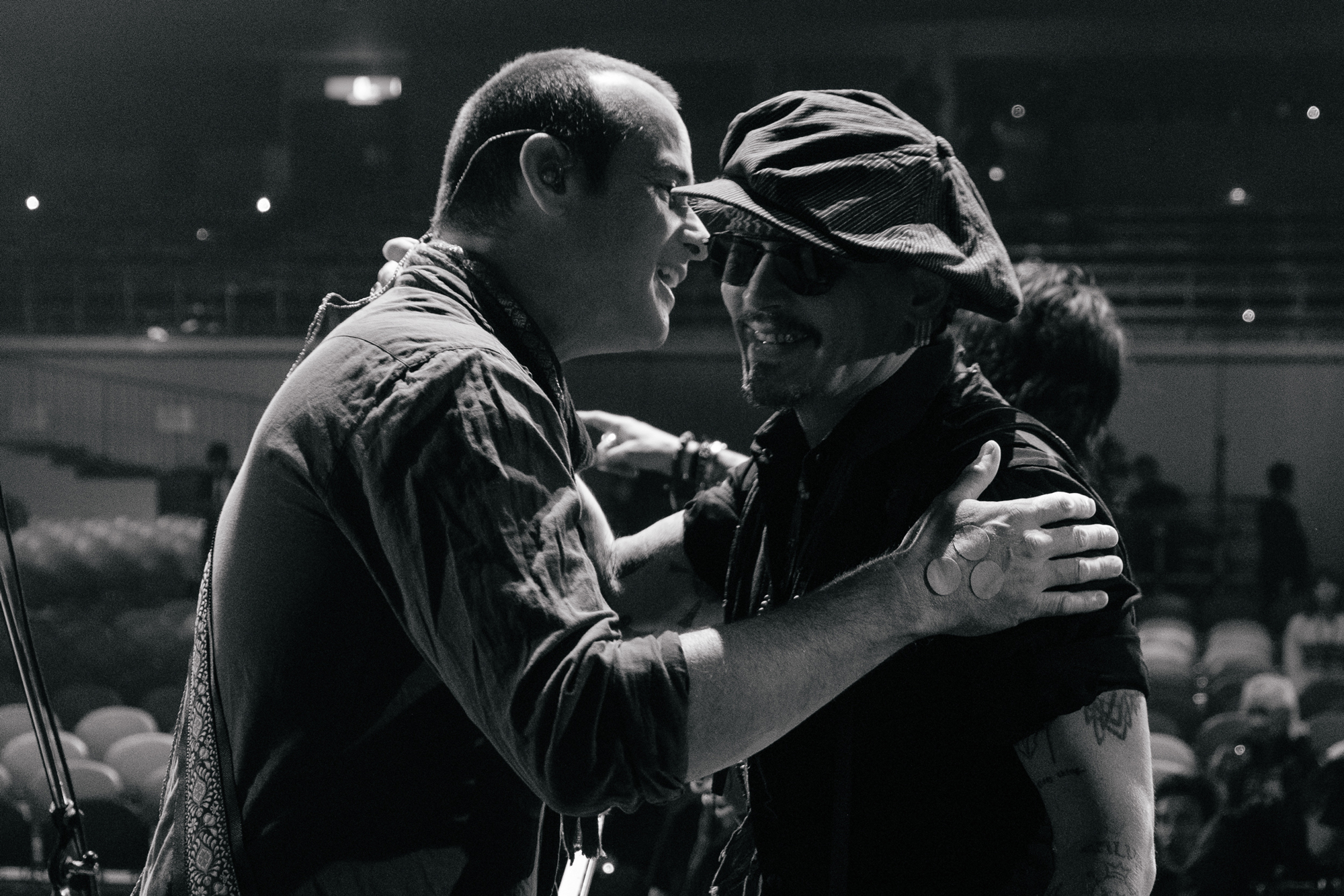

[Joe Perry comes in to say hello. When he leaves, Johnny says]

Joe Perry. The reason I picked up a guitar. I loved Aerosmith. I thought Joe’s licks were really fucking interesting. Half steps and just, you know, stretching a note just to where it’s juuust almost in key. He’s just got that feel, Joe. To end up being in a band with the guy, become pals and start playing together, it was amazing.

The interview is coming to an end – Joe Perry’s waiting, after all – but Johnny keeps on chatting: about Brian Wilson and the Wrecking Crew (“He was re-inventing and taking things to a different place”), about Captain Beefheart (“He did stuff that just blew me away”) and wanting to work more with Alice Cooper and take him back to “his early, early stuff… to loud guitars”.

“I’ve been very lucky about meeting heroes,” he says. He was nervous to meet Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck (“But Page, what a sweet fucker he is”) and reckons if Beck had retired after Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers he would have had nothing else to prove. He tells me a story about seeing Roy Buchanan when he was 14 (Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers was dedicated to Buchanan on Blow By Blow).

“He was a curmudgeonly bastard,” he says of Buchanan. “He liked a fucking tipple. He broke a string on stage and he proceeded to sit down on a drum riser and change it himself. And the more the audience got upset and booed, the longer he took. So he took like, 20-25 minutes to change the string. I was fucking howling…”

Scottish, I tell him – and I can say it because I'm Scottish – always gotta be difficult. There's a bonus track on the Hollywood Vampires album called Bad As I Am, written by Depp, Tommy Henriksen and producer (and former member of Depp's band The Kids) Bruce Witkin. Did he know Bad As I Am was a Scottish toast?

“Is it? I got it from the toast,” he says. “My stepfather was a fucking great man. He was like a great, great pal and a fucking good dad to me. I had my dad of course, but my stepfather came into my life and he learned me shit. He was an ex-convict and, yeah, he spent half his life in prison. So we’d drink he’d say, ‘Here’s to you, as good as you are, here’s to me, as bad as I am. As good as you are and as bad as I am, I’m still as good as you are, as bad as I am.’ Skol – bam! It just always stuck with me.”

Did his stepfather have Scottish in him? “He had fire in him, that’s for sure,” he says. “ He was a thief – a burglar – and just a survivor on the street. He always had these great things to say to me.

“If I hurt myself or whatever, he’d go, ‘Son, when you’re dumb, you gotta be tough,’” he laughs. “You know, those old dudes, they keep that language alive.”

At one point, it had been suggested that Depp might sing Bad As I Am at the Classic Rock Awards but there is no way he’s going to do that. “I just sing backgrounds,” he says. “Even as a kid in bands I avoided the spotlight, I stood back.”

Oh, the irony.

“You caught me before when you said, ’It must be great to be in a band, with other guys’. That was the weird thing for me when I started acting. Suddenly I was on my own. There was just me – and there wasn’t a guitar strapped to me. I didn’t know how to do a fucking movie. I just blagged my way through as best I could and then things got weird, you know.”

I’m sitting in the basement of a Sumo arena in Tokyo having a drink with Johnny Depp. They get weirder by the day, I say.

“They fucking do get weirder,” he chuckles. “They actually do. Surprisingly, shockingly, they get fucking weird.”

Originally published in December 2016 as "Johnny Depp Is just killing time until his band gets back together". Jeff Beck and Johnny Depp's new album 18 is out on 15 July and available to pre-order.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.