A Preacher, A Killer: the incredible story of Son House, king of the Delta Blues

How the life and legacy of one of the most influential bluesmen of them all was dragged from obscurity

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“They came to Rochester seeking an older black man who had been a blues musician in Mississippi before World War 2,” wrote blues historian Daniel Beaumont in his book Preachin’ The Blues: The Life & Times Of Son House.

“Their search had begun with some liner notes on a record album and some mistaken information from another blues musician about the man’s whereabouts. But following a trail of tips, they had finally spoken to the man himself by telephone from Memphis two days earlier.”

The rediscovery of Delta bluesman Eddie James “Son” House Jr is one of the most fascinating tales in 20th century music. As Beaumont reports in his highly-recommended book, the search for House took blues obsessives Nick Perls – “a skinny 22-year- old New Yorker” – and his two companions, Dick Waterman [then a freelance writer for The National Observer] and Phil Spiro on a journey into the deep south. “The trip – long, hot and cramped – had taken the three young men from New York City to Memphis. From that city on the banks of a new-world Nile, their search had led them down into sweltering small towns and plantations of the north Mississippi Delta.”

Article continues belowWhen they did finally track down Son House, they found him living in obscurity in Rochester, New York. House had given up playing music in the early 40s when he moved to the city. He who had run with Charley Patton, mentored and inspired Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters and cut blues masterpieces My Black Mama Part 1 and Part 2. The latter provided the foundation for his best known recording Death Letter Blues cut in 1965, a song knitted into the DNA of Jack White. House was a complex character. As a preacher, he’d once shunned secular music – or the devil’s music as it seemed to southern Christians. He killed a man in 1928 and found himself in Parchman Farm, aka the Mississippi State Penitentiary. On his release, he fell in with Charley Patton and his place in blues folklore was secured.

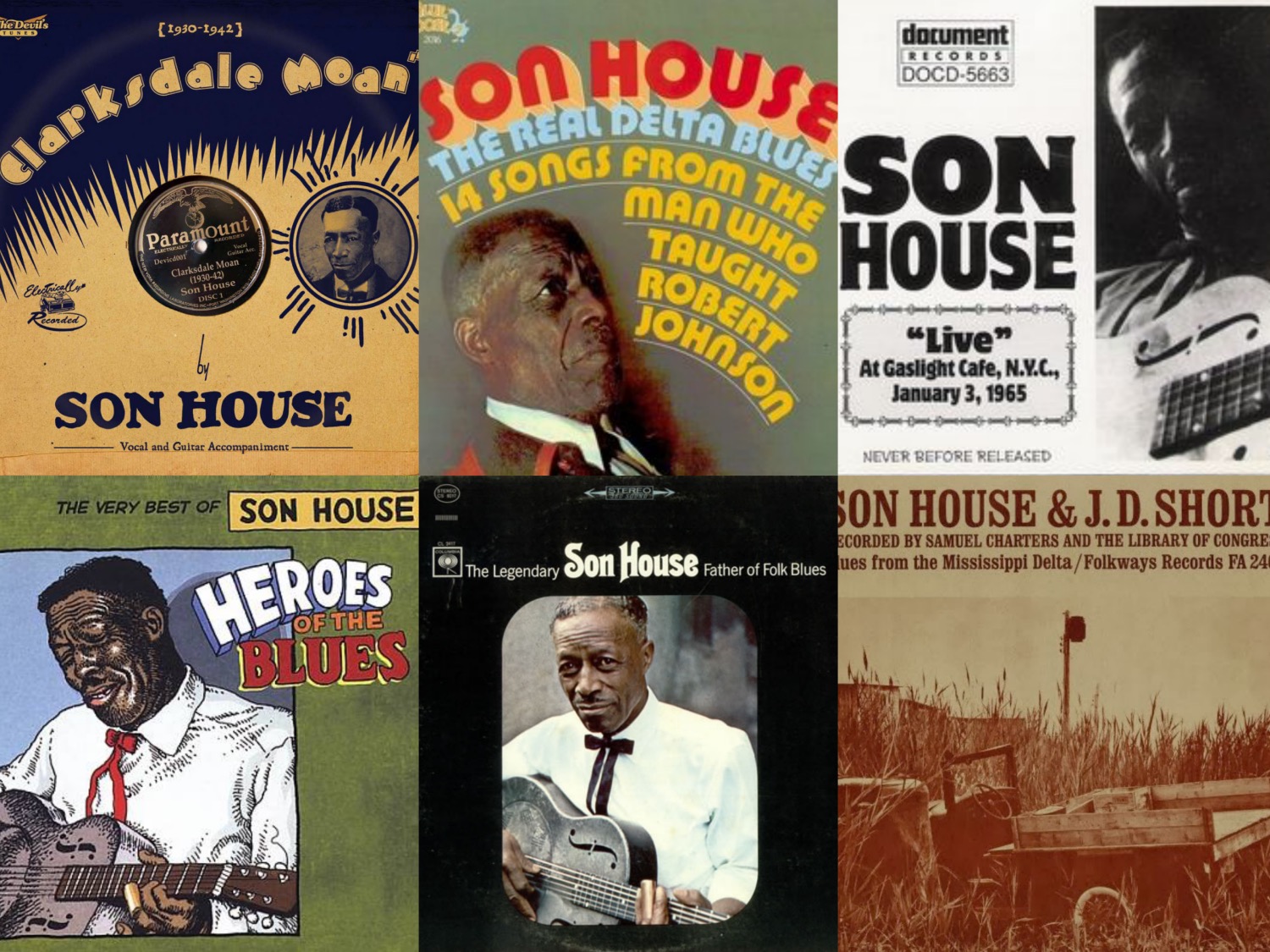

Robert Johnson’s rediscovery and subsequent icon status – though well deserved – has obscured the importance of Son House to all but the most informed of blues aficionados. A four-day celebration of the man’s life and legacy held in Rochester, New York last year told his story through music, theatre, film and lectures. It revealed how, after his rediscovery, House began recording and performing again – after relearning his style with the help of guitarist Al Wilson of Canned Heat. The Delta veteran found himself in demand again, not least in Europe, which is where we find him in this archive interview from Sounds magazine from 1970…

It was the final day of Eddie “Son” House’s final sortie away from the US. Outside, the rain was pouring down; inside the car sat Son, apparently oblivious to the surroundings, singing I Wanna Go Home On The Morning Train.

Someone broke the spell by pointing out that Son would be flying back to his home in Rochester, New York, and the old gent laughed good-naturedly and then nodded in concordance, as though humouring the other man.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

For a man of 69, it had been a strenuous tour, recording an album one minute, then appearing for the BBC, then a long drive to a northern venue, back to London’s 100 Club and so on.

Yet throughout the entire month, Son was never less than dignified and amicable as he chatted affably with the hundreds of European blues hounds who milled to catch a few words with the great man at every gig he played. It was as though Son, neatly clad in frilled shirt, bow tie and ubiquitous hat, was determined to put on a good stand as the sole survivor of the idiom which produced from the deep south men like Charley Patton, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Robert Johnson and Skip James, and their progeny Bukka White and Muddy Waters.

Son House is akin to an opening batsman who is still undefeated when the innings is closed and all the others are out. His return to New York State for the last time is a sad farewell, for his retirement marks the end of an era.

The tour had only been made possible because of the close link between Dick Waterman and The Blues Foundation, coupled with the bona fide intention of both factions to put a little cash into Son’s pockets for his retirement.

“Sure I enjoyed the trip but I wanna have finish with all the thissin’ and thattin’; I wanna git back to Rochester and see if the ol’ lady’s still there,” Son remarked.

But he was happy to cast a tired and troubled mind back across the rugged path, which has been lifted straight out of context for the interest of endless blues devotees. From the horse’s mouth, so to speak, the recounting of Son’s profligacy seemed all the more stark and paradoxical.

“Five or six years ago now I ran into a little trouble and had to kill a guy. I spent eight days in jail in New York City, but the judge and everybody, they knew it wasn’t my fault, and that I had to do it, and they let me go out on probation or somethin’. Some years ago when I was younger I used to get into a little more trouble because I didn’t have the brains I should have had then. If my mind had been like it is now, then I wouldn’ve been stuck in jailhouses and pens,” Son admitted, making his tale sound for all the while as though he were reading it straight from a story book.

“I like friends, and I don’t want to know about no nasty folks. Because I didn’t keep track of some of these guys, [that’s] why they’ve beaten me outta money, cos I was an easy guy to get along with. I got some money, but never nothing like what was due to me. D’you know, one guy promised me money for a recording and I didn’t see him no more for 10 or 15 years. Then we was at the Newport Festival and I says to Dick: ‘Yonder goes that guy.’ But I still don’t think I got all my money.”

Son is fully aware of his unique position. A legend in his own lifetime is one of the great misused phrases, but it could be fitted into every sentence of Son’s eulogy. He is now in frail health and suffers from short pangs; his hands are badly frostbitten and he knows that his time will come.

“All ’em old boys has left me by myself; they’s all dead and gone – Charley Patton, Blind Lemon, Willie Brown, Skip James,” he says. “I’m 69 now and it won’t be long before I’m 70; I may be old but you know I still have young ideas. I’ve been having these short fits – not illness like most people, sick and all that, but sometimes at nights I have some kind of spells and I’ll die like that one of these days. I don’t know I been ill but my ol’ lady tells me in the morning: ‘You know you was ill again last night.’”

But Son’s words are not pre-dooming, and scarcely conjure up any presentiments and premonitions; he is a happy man, with faith and determination. “A man’s mind, you know it has a lot to do with him; you can knock yourself out with it but you can do what you think you can do and what you’re determined to do.”

Gradually, the many qualities of Son House come to light, so that by the time you’ve finished talking to him you are thoroughly overcome by the impeccability of the man, who positively exudes the many blessings which make up perfection. Modesty is, perhaps, his chief asset.

What’ll you do when you get back to Rochester, Son?

“Why I’ll jus’ be cocking up my heels and resting awhile, watching TV as usual.”

What he didn’t mention was the fact that he was invited to play the final set on the final night of the mighty Ann Arbor Festival, which contained just about every famous blues personality. “It’s a massive festival, and only fitting and right that Son should be asked to provide the climax. The most he will do after that is a very occasional major package in the States, and the universities,” interrupted Dick Waterman, who in recent years has nurtured the blues like a newborn baby, and looked after the welfare of Skip James, Mance Lipscomb, JB Hutto, Mississippi John Hurt, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Arthur Crudup and others.

“It was in 1927 that I started playing what I call the real blues; just before that I didn’t like the blues because I was too churchy for all that. But when I saw these other guys playing then I wanted to learn too,” Son recalled.

He was particularly fascinated by early bottleneck players around his hometown of Clarksdale, and he adopted his own method of producing the whine up the treble strings – a copper ring which was to become the trademark of his music. Son is now using a piece of copper tubing, and has been known to use other implements including a penknife.

“I was born and raised in Clarksdale but Charley [Patton] was living in Jackson, Mississippi when I first ran into him. I couldn’t play the blues like him by just learning straight off. So I stayed around with him for a little while, then I moved on and ran into Willie Brown. We started playing together, Bill and me, and soon after that Charley was recording for Paramount and he wanted someone to play with him.

“I think Charley had heard people braggin’ on me, so me and Willie was talked into going down. So then there was Willie, me and Louise McGhee. Blind Lemon was way up ahead of us, and he left us there.”

Charley Patton, Willie Brown and Son House all recorded for Paramount at Grafton, Wisconsin in May 1930. House’s sides included versions of My Black Mama, Preachin’ The Blues, Dry Spell Blues, Clarksdale Moan, Mississippi County Farm Blues and What Am I To Do Blues.

Muddy Waters, who also came from Clarksdale, is reported to have told writer Paul Oliver that Son was the best bluesman to play the jukes around Clarksdale. Muddy recalled that Son came from a plantation east of Clarksdale and played with the neck of a bottle over his little finger. Muddy admits to getting the idea from Son House, but felt that Son never came over as well on record as his live performances.

“A man from Jackson wanted us to make some records and he thought we was all sanctified folks, but we was just whiskey drinkers,” mused Son.“Then Charley died of pneumonia and me and Willie was up in Robinsonville at the time, and they wrote us a special; but there wasn’t nothing we could do nohow, so we just stayed right on and didn’t go the funeral.”

Around August 1941, Son and Willie recorded at Lake Cormorant for the Library Of Congress, and House’s Shetland Pony Blues, Fo’ Clock Blues, Camp Hollers, Delta Blues and Going To Fishing were subsequently released.

Son cut a further eight tracks for Alan Lomax at the General Store in Robinsonville in 1942, which were among his best sides. Six of these were reissued on an Xtra album with Jaydee Short. The sides are Sun Going Down, I Ain’t Goin’ To Cry No More, This War Will Last You For Years, Am I Right Or Wrong, My Black Mama and County Farm Blues. The other titles, Son’s famous Jinx Blues and The Pony Blues, a variant of his earlier Shetland Pony Blues, have recently been reissued on Roots. But most of the tracks have been retitled since they were originally recorded.

Son was given time off from the plantation to record for the Library Of Congress: “I was a tractor driver for six or seven dollars a week, but it didn’t matter what you went out and did to yourself at the weekends so long as you was there ready to start on Monday morning. Willie and me had moved back from Jackson about 25 miles south of Memphis, Tennessee; we weren’t making much money and I was drivin’ the tractors and ploughing the mules. At the weekends we played the juke joints and rent parties. We didn’t sleep on Saturday night, then we’d play on all day Sunday and Sunday night.”

Son’s Library Of Congress recordings are significant, for they revealed him as a folk artist as well as a rough-edged blues singer. For example, This War Will Last You For Years is a song about the second world war, the words of which Son still remembers clearly. “There won’t be enough Japs to shoot a little game of crap,” Son recalls with a laugh. But on a more serious note, his County Farm Blues was a straightforward directive at the plantation farm gang system by which he and his fellow men were exploited.

These Library Of Congress sides are also important because they marked Son’s final association with the rural south. The following year he moved up to Rochester and lived in relative obscurity until his rediscovery by Dick Waterman in 1964. A year later he cut nine sides for Columbia with the assistance of his old friend Al Wilson from Canned Heat on harmonica. Thus the star had been reborn.

Since 1966, though, Son House had only recorded once, a very poor performance for Roots which had failed to capture any of the emotion and lyricism which we could expect, prior to his recent tour.

But the two sessions which took place before enthusiastic audiences at the 100 Club in Oxford Street, London, were indeed exemplary, and released on Liberty.

Said Dick Waterman: “Al Wilson was at the first session, and [Canned Heat guitarist] Henry Vestine too. In fact Al was playing better than I’d heard him in years.”

Earlier Canned Heat frontman Bob Hite had remarked that during Canned Heat’s stay in England it was unlikely that the path of the group would cross with that of Son House. On the previous occasion, Son had failed to recognise Al – a typical sign of the old blues singer’s fading memory.

“Son didn’t play badly anywhere on the tour,” Dick Waterman concluded. “But we came in four days later than expected, and were moving around staying overnight which was very tiring just before the St Pancras gig. Unfortunately, this was the one where everyone went to judge him, and it was unfortunately his worst. The next day he was great, and he should now really be playing four or five times a week. The trouble is that Son is almost incapacitated by the third finger on his left hand, so now he can only play in open tuning. He got frostbite back in January and will be seeing a doctor as soon as we get back.”

Anyone who follows Son’s progress across England will agree that there was nothing as bad as that terrible opening gig, and by the time he came to record all the magic had returned – the vocal intensity matching the flamboyant sweeping across the strings with the right hand, and the primitive indecisive “steeling” with the left. Levee Camp Moan, an untitled blues, Good Morning Little School Girl, I Wanna Leave On The Morning Train and This Little Light Of Mine were captured at the first session, plus How To Treat A Man, Death Letter assisted by Dave Kelly, and two unaccompanied hollers, Grinning In Your Face and John The Revelator, which Son also recorded for Columbia.

Throughout the tour – in fact throughout his career – Son has been involved in the church-versus-blues syndrome, and he is still careful to keep his religious and non-religious songs apart.

It is also interesting to note that while Son’s appraisal of the blues is no more than the fundamental problems between man and woman, he will not sing any songs which he calls “foolish”.

“I don’t like no foolish songs; I like ’em to mean something. Those songs have got to be about something.”

At the same time, Son House has marked a penchant for the introductory prefaces to his songs – little fragments of Son House philosophy, mostly with religious connotations, directed at a hushed audience, like a preacher addressing his congregation. Then, without further introduction, Son would pound into Levee Camp Moan, or Empire State Express or Death Letter and we would see not only the great man himself come alive, but also everything within striking distance. Of course, he can still perform – it is no matter for conjecture; certainly not comparable to a crowd of admirers gathering round an effete steam engine which is no longer functional but preserved for posterity. Rather the experience of a Son House performance is like witnessing the engine firing on all pistons – a study in kinetics with each part flowing as gracefully as the next.

Because of the mystique surrounding that other great Delta bluesman, Robert Johnson, Son House has tended to be slightly overshadowed. Thus it was interesting to hear first-hand of Son’s encounter with Robert and a further aid to understanding the chromatics and semantics of the blues environment.

“I first met Robert in 1933, I think in Robinsonville. I got friendly with his mother and father, and he was blowing Jew’s harp. Why, even then he could blow the pants off just about anyone, but he wanted to play guitar. When he grabbed a guitar, the people would ask why don’t he stop; he was driving ’em all crazy with his noise. Then he slipped off to Arkansas somewhere, but sure enough he came back and he found us. We was asking if he remembered what we’d showed him, but then he showed us something, and we didn’t believe what we saw. I said to old Bill: ‘That boy’s good.’

“But Robert was too quick to get excited and he’d believe everything the girls say; they’d be saying things to him and he’d be thinking they was meanin’ it; but we told him they didn’t mean no good, and he went and got killed on the levee camp.”

Son House and Dick Waterman have an acute understanding and Son is obviously pleased that Dick gave him the chance to work again. Earlier in Rochester, he worked as a porter at the New York Central. “But I quit the job and made up a song Empire State Express. Then I went back to the church for a while; cos if I see I’m doing the right thing, then I like to get on one side or the other and not straddle the fence.

“I don’t care as much about playing as I used to, and I’m not writing any new songs, although I don’t take no one else’s. I move the verses around, and although it don’t take long to write a new song, the trouble is managing to hold ’em. Sometimes I didn’t play for three and four and five years, and when you lay off for that long you miss a whole lot of it because your mind goes off and you forget a lot of the words.

“Dick’s been good to me – he’s a good boss. He got me another National guitar because mine was stolen while I was asleep. He already had Skip, so after he got me, he pulled us both together. I’m happy now playing a little round Rochester, and there’s a few royalties once in a while.”

The music of Son House and the heritage of American black culture have been passed down, and the style of music is now being expedited by people like Bukka White and Joe Williams, and the newer wave of Chicago musicians like Johnny Shines, JB Hutto and, of course, Muddy Waters. A lot of blues singers have been vastly over-recorded over the years, and a lot more have not been given the opportunities they deserved until they have been far too old to work. Such is not the case with Son House.

In June and July this year we heard the music as it was and also managed to apprehend a little from the man about his life and times. But the sight of an old man wrestling with his heavy steel guitar is a sad one and, I suppose, we are fortunate in having caught a glimpse of Son House at all.

Son’s album will be released by Liberty. It will be entitled John The Revelator, and opens with a monologue on the blues. Son then breaks into Between Midnight And Day, a slow blues with harp accompaniment provided by Canned Heat’s Bob Hite. Al is also present on I Wanna Go Home On The Morning Train, which precedes a new version of the much-recorded Levee Camp Moan. Son’s slow version of the gospel song This Little Light Of Mine leads into a monologue on God and the devil. Side two opens with a monologue on “thinkin’ strong” and then comes the favourite, Death Letter Blues. An incredible 15-minute version of How To Treat A Man, with Dave Kelly on second guitar, gives way to the two unaccompanied numbers John The Revelator and Grinning In Your Face. It’s a revelation of its own.

Son House - The essential playlist

Walkin’ Blues (1930)

Unknown until modern times, this turned up as a test pressing in a pile of discs destined for a dumpster. House later recorded the song solo, but here Willie Brown plays second guitar. It’s House’s most obvious legacy to Robert Johnson.

My Black Mama – Parts 1 and II (1930)

The guitar riff is that of Walkin’ Blues, but compared with that one-act play this six-minute performance is a full-length drama, relentless in its momentum. ’Tain’t no heaven, tain’t no burnin’ hell, where I’m goin’ when I die, can’t nobody tell.’

Preachin’ The Blues – Parts I and II (1930)

House testifies from the border between righteous and riotous, the life of a saved man and that of a man lost in the blues. It’s hard listening – no copy survives in good condition – but a masterwork.

Mississippi County Farm Blues (1930)

The death of Blind Lemon Jefferson was recent news, and House remembered him with a song based on his See That My Grave Is Kept Clean. It took three quarters of a century before a copy of this Paramount 78 was found.

Levee Camp Blues (1941)

House’s first recording for the folklorist Alan Lomax, a thick weave of sound, House’s slide guitar knotted around with harmonica, mandolin and second guitar. Imagine rolling up to a Saturday-night juke joint and finding these men were the band.

Camp Hollers (1941)

Lomax asked for unaccompanied “field hollers” and House obliged with this medley of verses from prison and levee camp life, appreciated and encouraged by his fellow musicians. No guitar, but the rise and fall of House’s voice is music enough.

The Jinx Blues (No 1) (1942)

From his second session with Alan Lomax for the Library Of Congress comes this demonstration of how close House was to Charley Patton – the snapped-string descending bass figure matches Patton’s on numbers like Moon Going Down.

Death Letter (1965)

Uncertain but hopeful, a generation of blues enthusiasts bought House’s comeback LP The Legendary Son House – Father Of Folk Blues, put it on, heard this, and breathed a sigh of relief. The old man had still got it. Or most of it.

Empire State Express (1965)

Another track from House’s “rediscovery” LP, this song, like Death Letter, remained in his repertory for the rest of his life. Here Canned Heat guitarist Al Wilson underpins House’s guitar part, accelerating with him to a triumphant climax.

Grinnin’ In Your Face (1965)

House wavered all his life between worldly music and God’s, and never let his audiences forget it: no performance passed without a sacred song, and this was his favourite. ’Just bear this in mind – a true friend is hard to find.’