How Stone Temple Pilots made Core and became the most hated band in rock

Right from when Stone Temple Pilots began, they were pilloried like no other band before or since. They became one of the great groups of the 90s, but those wounds never fully healed

In an episode of one of the most popular TV shows of the early 90s, there’s an exchange that sums up the prevailing critical view of Stone Temple Pilots when they first came along. In it, those two unlikely arbiters of cool, Beavis and Butt-head stare blank-eyed out of the screen as the video to STP’s hit single Plush plays. “Is this Pearl Jam?” cackles Beavis.

“Yeah, Eddie Vedder dyed his hair red,” snorts Butt-head.

Beavis: “Wait a minute. This isn’t Pearl Jam.”

Butt-head: “They both suck.”

Beavis: “Pearl Jam doesn’t suck. They’re from Seattle.”

In that brief conversation, those animated sofa-dwellers with the single-digit IQs neatly summed up the reception the Los Angeles band had received from sections of the mainstream music press: they were copyists, opportunists, bandwagon jumpers. They had the temerity to sign to a major label without putting in the hours on some godforsaken indie label than no one but the hippest hipster knew about. Jesus, they weren’t even from the right city.

The vitriol heaped upon Stone Temple Pilots was vastly out of proportion to their supposed crimes against cool. The band’s debut album, Core, was simultaneously confident and pained, anthemic and intimate. Sure, it slotted neatly into prevailing trends, and yes, singer Scott Weiland’s chameleonic baritone evoked both Eddie Vedder and Kurt Cobain. But Stone Temple Pilots were their own men – and men of the people at that, as the eight million people who bought Core can testify.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

If there’s a band that Stone Temple Pilots should be compared to, it’s Led Zeppelin. Not musically – the surviving members of STP aren’t foolish enough to draw a parallel there. But certainly both bands were forced to endure an inordinate amount of shit being undeservedly dumped on them early in their careers, and both eventually rose above it with dignity and pride intact.

“We grew up listening to bands like Led Zeppelin, who got heavy criticism,” says bassist Robert DeLeo, a man with the slicked-back hair, deep-set eyes and warm vocal tones of a 1920s stage hypnotist. “When you model yourself on someone you admire, and you see they got the slings and arrows too, it gives you a kind of strength. The whole mentality of STP at all times was: ‘Let’s write the best songs.’ That’s what it was all about. It was honouring the craft of the song.”

In 2017 Core turned 25, and the craft DeLeo talks about hasn’t just stood the test of time, it has aged better than many of its contemporaries. While the journey since taken by the band that made it has been marked by breathless highs and heartbreaking lows, the album that started it off stands as a validation of everything Stone Temple Pilots set out to achieve.

Robert DeLeo moved to Los Angeles in 1984 with $1,200 in his pocket and ambition in his head. He and his elder brother Dean had grown up on the other side of America in small‑town New Jersey, where they spent their early years listening and playing along to Led Zeppelin, T.Rex and Cheap Trick.

It was in LA that Robert met a skinny suburban kid named Scott Weiland. Cleveland-born but raised in Orange Country, Weiland was an all‑American quarterback type with a wild streak a mile wide. As a teen he’d dabbled with marijuana and cocaine and been sent to rehab by his mum and stepdad for his troubles.

“He was a completely different person back then,” says Robert. “He was fresh out of college, kind of on a fratboy, jock kind of trip. He was very energetic, very alpha male. But he definitely had the gift of singing.”

Weiland and his best friend, guitarist Corey Hickok, had a band called Soi Distant, whose pretentious, would-be European-sounding name was matched by their pretentious, would-be European-sounding music. A chance encounter with Robert DeLeo prompted them to ditch the Duran Duran and Ultravox influences and form a new band, Swing. Soon the trio were joined by drummer Eric Kretz.

“We were into the more funky, James Brown-meets-rock type of thing,” Kretz recalls. “The stuff Robert and I were really trying to do was in that Zeppelin, James Brown, Grand Funk Railroad vein, with funky backbeats underneath the rock music. The songs were a lot more silly.”

But every chain has a weak link, and Swing’s was Corey Hickok. In 1989, Robert suggested the band bring in his brother Dean as a replacement. Dean was approaching 30 and living in San Diego, where he ran a construction firm. But he’d never given up the guitar, or the dream of becoming a musician.

“I was asked to play some solos early on, and it was pretty evident that they needed to make a change,” says Dean. “I was just getting on with my life, and they said: ‘Hey, man, why don’t you join the band?’ Corey was Scott’s best friend, and I think it was hard for him. But he knew that the band had to grow and expand.”

Dean insisted the band change their name to mark a fresh start, and Swing became Mighty Joe Young, after the black-and-white 1949 King Kong knock-off. It wasn’t the only thing that was different. “When Dean joined the band, the dynamics changed and the songwriting changed,” says Kretz. “We got a much more hard rock type of sound. As far as the lyrics Scott was coming up with, a lot of the joking and silliness went. And his vocal approach got a lot heavier. He started channelling Jim Morrison and David Bowie.”

Life in a struggling band in LA was tough. Robert DeLeo earned a paltry wage working in a guitar shop amid the hookers, drug dealers and dreaming musicians on Sunset Strip. “Working at the guitar shop and seeing some of these hair-band guys come in was an education,” says Robert. “Every one of those could play really great, but it was a blueprint of how not to treat people.”

His job put Robert on the front line of the LA music scene, watching the changing of the guard as it happened. The glam-metal groups still ruled the streets, but there was a new breed of bands waiting in the wings, including Jane’s Addiction and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. “It felt like something was happening,” he says now. “And it felt like we could be part of it.”

While Robert was selling axes to soon-to-be-has-beens, Weiland was working across the street at a model agency, chauffeuring beautiful women to assignments around town.

“It was great because I would have an idea and run over there real quick, or he’d have an idea and run over to me,” says Robert. “Scott was very focused; he was like a lion. He was very ambitious, very passionate about all aspects of being in a band. Lyrics and music and success – he wanted it just as much, if not more, as the three of us.”

Weiland was undergoing a change. When he and Kretz moved into a loft apartment in downtown Los Angeles, the drummer watched his bandmate transforming before his eyes. “I saw him delving a lot more into the arts – poetry, strange novels, watching really avant-garde movies,” says Kretz. “You gotta develop this ‘tortured artist’ intellect, and you have to be able to express it in your own form. And that’s what he did.”

Hollywood in the early 90s wasn’t a million miles away from Hollywood throughout the 80s. Money ruled everything. The Sunset Strip clubs had a pay-to-play policy, which meant a band had to bring in a few hundred people just to cover the outlay. For Mighty Joe Young, that was easier said than done.

“We were always on the outside,” says Kretz. “You hear about these unsigned bands that have this huge crowd base and have a thousand people at their shows. We were never that band.”

They managed to bag shows at venues with names like Club Lingerie and The Coconut Teaser, and 100 miles down the Pacific coast in San Diego, where Dean DeLeo lived.

It was at a long-forgotten East Hollywood dive called Shamrocks where the future suddenly opened up for them. They had recorded a demo comprising a handful of songs that eventually ended up on Core. The demo tape came to the attention of Atlantic Records A&R man Tom Carolan, who saw the band at Shamrock and offered them a deal. He also suggested they find a new name, as Mighty Joe Young was already taken by an aging bluesman.

As a kid, Weiland had been weirdly fascinated by STP Oil Treatment, a lubricant used in motor engines. He suggested they fit a name around the initials. One early suggestion, Shirley Temple’s Pussy, was rejected for being too fratboyish. But the next one stuck: Stone Temple Pilots were born.

Over the course of a few months at the end of 1991 and into ’92, STP recorded their debut album with producer Brendan O’Brien at Rumbo Recorders in the San Fernando Valley. Some of the songs that appeared on their demo were retooled for the album. Newer tunes were added, among them the stuttering Sex Type Thing, an anti-rape song that found Weiland assuming the character of the protagonist with barely concealed distaste (something which the band’s critics later seized upon with misguided glee), and Plush, a vivid if abstract dissection of obsessive relationships partly inspired by the story of a murdered woman in San Diego. According to the DeLeos and Kretz, the sessions were a breeze.

“We all had the same vision at the time,” says Robert DeLeo. “As you can see from the history of the band, that didn’t always last. But back then there was a strong camaraderie and vision for what we were trying to achieve with that record.”

Released in September 1992, Core was a confident debut. While it nodded to the prevailing alternative rock trends that had been shoved front and centre by the success of Nirvana and Pearl Jam, it also had a flavour of its own, not least in Dean DeLeo’s complex, textured guitar work. Stone Temple Pilots knew they had a good record, one that did justice to their illustrious forebears on Atlantic.

“Since we’d signed to Atlantic Records, which was one of the greatest labels in the world, I was like: ‘If we fail and get dropped, there was no coming back from getting dropped from the top,’” says Eric Kretz. “That was my biggest fear.”

His concerns proved unfounded. Thanks to help from MTV, who pushed the videos for Sex Type Thing and Plush, the album started to sell steadily. It helped that they had a magnetic frontman who embraced the limelight while so many of his peers pushed it away. Unlike Kurt Cobain or Eddie Vedder, Scott Weiland was a natural‑born rock star.

“I’ve got to tell you that term, ‘rock star’, I don’t care much for it,” says Dean DeLeo. “But I never really looked at Scott like that. I looked at him like my brother. He was my brother, and we were in this thing together. We all wanted the same thing – to make an indelible mark on the face of music.”

In November 1992, STP embarked on their first national tour. Holed up in an RV with an equipment truck trailing them, they criss-crossed America, stopping off at such sweatboxes as Washington DC’s 9.30 Club, the Phantasy Nightclub in Lakewood, Ohio, and Club Downunder in Tallahassee, Florida. Not every show was a ringing success. At one gig in Buffalo, New York, the band counted seven people in the venue, as well as themselves – including the bartender and the bouncer. The next night, in Toronto, the club they played was sold out.

Their mettle was tested early the following year when they opened for thrash linchpins Megadeth. Every night they would face down a front row who would flip them the bird or simply turn their backs.

“Scott really had to start working the audience,” says Kretz. “They hated him, they hated us, they hated anybody who was opening for Megadeth. We definitely earned our stripes on that tour.”

While Stone Temple Pilots were out on the road, Core began to cook with gas. The success of the Seattle bands had spawned a public appetite for anything that sounded grungey, edgy, anthemic and preferably all three, and STP fitted the bill.

“I don’t know if you could ever be prepared for that rocket ride,” says Robert. “Our A&R guy, Tom Carolan, said something I’ll always remember: ‘You gotta fasten your seat belts.’ He was right. We were on the road for fourteen months. Not a lot of people can do that. But it’s the mental and emotional side of what occurs that plays with your soul.”

If anyone was playing with Stone Temple Pilots’ soul, it was the media. While the band had their champions in the rock press on both sides of the Atlantic, the mainstream media piled in on them. The New York Times compared them unfavourably to Pearl Jam and Nirvana; Rolling Stone voted them the Worst New Band Of The Year.

From being a cool little outfit doing their own thing in the LA clubs, STP suddenly became the press’s whipping boys. They were accused of everything from cynical plagiarism to the corporatization of grunge. The criticism snowballed – it became a weird form of schoolyard bullying. Eric Kretz and Robert DeLeo look back on it all with the grace that only a quarter of a century’s distance can bring. “Sometimes you just take the punishment,” says Kretz. “You just say: ‘You know what? I can turn it around to my benefit.’ And critics aren’t always right.”

“We weren’t making records for them,” says Robert DeLeo. “Most of those people didn’t even listen to our records. They just kind of copycat wrote what everyone else was writing.”

Dean DeLeo is a different matter. The critical kickings meted out to the band still rankle after all this time. When the subject is brought up, there’s a pause, and the conversational temperature drops by several degrees.

“I’ve been making records for twenty-five years,” he says eventually. “So I’ve earned where I don’t need to entertain a question like that. If I was asking you questions, and you had a decade and a half under your belt, I wouldn’t ask that kind of question. You’re asking me about something that happened twenty-five years ago. I wouldn’t even know how to answer that.”

If the criticism hurt the band, it certainly didn’t hurt them commercially. By the end of 1993, Core had topped three million sales. But there were darker clouds gathering on the horizon – ones that would irrevocably change the band.

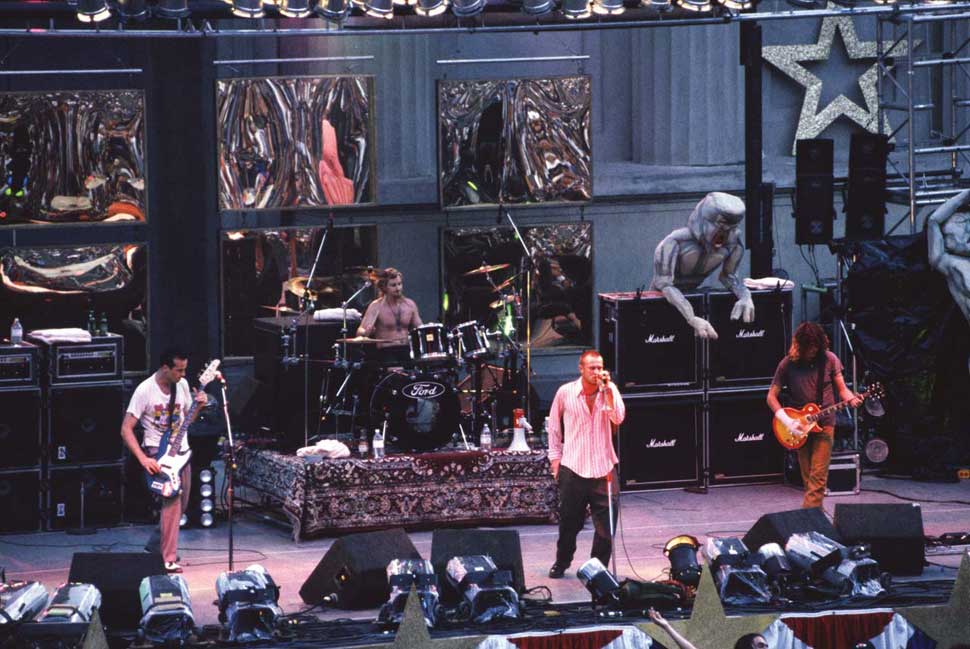

On June 12, 1993, Stone Temple Pilots kicked off their Bar-B-Q-Mitvah Tour, a kind of mini-Lollapalooza package tour also featuring Texan loons Butthole Surfers, Oklahoma weird-beards the Flaming Lips, funk pioneers Basehead and cult punk heroes fIREHOSE.

“We told the promoters we want to do shows where shows haven’t been done – like fishing ponds and golf courses,” says Kretz. “Lollapalooza was out at the time, and they were trying to do something different. We thought: ‘How do we do something different? Well, fuck it, let’s try to make something all our own.’ And it was quite a big party.”

For Scott Weiland, that party was about to spiral out of control. In his autobiography, 2011’s Not Dead And Not For Sale, the singer recalled his fascination with heroin – or at least its then-distant allure. “I associated heroin with romance, glamour, danger and rock’n’roll excess,” he wrote. “More than that, I was curious about the connection between heroin and creativity. At that point, I couldn’t imagine my life without at least dabbling with the King Of Drugs.”

When the tour hit New York, Weiland decided to take the plunge. When other, unnamed musicians clubbed together to buy some China White heroin, he added his name to the order. For that night’s show, Stone Temple Pilots decided to dress up as Kiss. Before he hit the stage in his Paul Stanley drag, Weiland snorted heroin for the first time. “I was undisturbed and unafraid,” he recalled. “A free-floating man in a space without demons and doubts. The show was beautiful. The high was beautiful.”

No matter how he gussied it up in poetry, a line had been crossed – one that the singer would never truly come back across.

“The start of his heavy drug intake definitely came towards the end of that tour,” says Kretz. “Before that we were all heavy drinkers. I’d watch him drink until he passed out. He didn’t do it all the time, but it happened. But that tour changed things. He learned some bad habits, and unfortunately they stayed with him.”

By the time the campaign for Core was over, the album was well on its way to selling eight million copies. Success provided scant armour against the brickbats of the press. Instead, STP doubled down and channelled their anger, frustration and songwriting craft into a glorious follow-up, Purple. Like its predecessor, it sold in the multimillions – and it silenced their critics.

But for Scott Weiland, success – and curiosity – came at a cost. His on-off-on-again drug habit would define his life over the next 20 years as much as his music did. He fell into a tragically predictable cycle of arrests, rehab and relapses, while his relationship with his STP bandmates ebbed and flowed, with singer and band splitting and reuniting multiple times over the years, like a married couple who couldn’t live with each other but couldn’t live without each other too.

In December 2015, the inevitable happened. Weiland was found dead in the bunk of his tour bus before a gig in Minnesota with his new band The Wildabouts. A combination of drugs was found in his system. The cause of death was determined to have been an accidental overdose of cocaine, MDA and alcohol. His former bandmates in Stone Temple Pilots released a statement paying tribute to their fallen colleague: “You were gifted beyond words. Part of that gift was part of your curse.”

“I think about Scott a lot,” Robert DeLeo says now. “Every single day. Every aspect of his character, from the beginning of the band to the day he passed. We went through a hell of a lot together.”

The deluxe 25th-anniversary reissue of Core stands in part as a tribute to Weiland, but also as a marker of Stone Temple Pilots’ tenacity. Other bands would have crumbled in the face of opprobrium, but STP didn’t just transcend it, they turned the tables on their critics. Today, they should finally get the respect they deserve.

“Man, we were just so young and hungry back then,” says Eric Kretz. “We were fired up to make a difference, we truly were. We were on the cusp of an exciting movement in rock’n’roll, and we were part of it. No one can take that away from us.”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.