“We weren’t doing electronic music with synthesisers, but with a bank of oscillators we stole from radio stations”: Jean-Michel Jarre and the creation of Oxygène

A story of challenges, limitations, the completion of its 40-year journey and working with Stockhausen – who “considered himself to be made of sound”

In 2016 Jean-Michel Jarre released Oxygène 3, marking the end of a journey that began with his 1976 debut Oxygène. That year he looked back with Prog on how he’d been inspired to make the original, how it became the dominating record of his career, and the approach that inspired the last chapter of the story.

These are heady times for Jean-Michel Jarre, even by his own lofty standards. His two Electronica albums – 2015’s The Time Machine and this summer’s The Heart Of Noise, featuring top-notch guests like Tangerine Dream, Massive Attack, Hans Zimmer, Laurie Anderson, The Orb, John Carpenter and many more – were huge hits across Europe, taking him into the UK Top 10 for the first time in 25 years.

Their combined success led to an extensive tour of the continent this autumn, packing out arenas from Cardiff to Copenhagen, Brussels to Budapest. At 68 years of age, and bearing in mind this is a man who’s shifted 80 million albums over his career, Jarre’s commercial and artistic clout is arguably at its peak – or at least on a similar level to 1977, when Oxygène took him from jobbing composer of library music to full-blown international superstar.

Given this evaluative symmetry, it’s entirely fitting that Jarre has now chosen to release a third volume of Oxygène. Not that he deliberately planned it that way. “During the Electronica project, I did a track that wasn’t sitting at all with the other songs,” he tells Prog. “I kept that idea in the back of my mind. When the record company mentioned that they’d like to do something special for the 40th anniversary of Oxygène, I thought it might be good to use it as a deadline pretext.”

Nominally, of course, the new album is a sequel to 1997’s Oxygène 7-13, but Jarre was more interested in following the original as a working model. “I did the first Oxygène album in six weeks with very limited tools,” he explains, “so I thought it would be fun to go back into the studio with the same minimalist approach, especially after the massive Electronica project, which involved a lot of planning, travelling and heavy production.

“I didn’t go back and listen to the previous work at all. The plan wasn’t to revisit the original Oxygène, or use the same kind of instruments. That would have been pointless. But I kept the same dogma. Oxygène is not so much a series of songs with separate titles – it’s more of an overall concept, like a movie or a series of short stories. I thought, ‘Okay, I’m going to stay with a limited number of elements here, and sometimes just have parts that use only two or three instruments.’ So I did it all in one go, keeping it rough like that, then went on tour and left it behind me.”

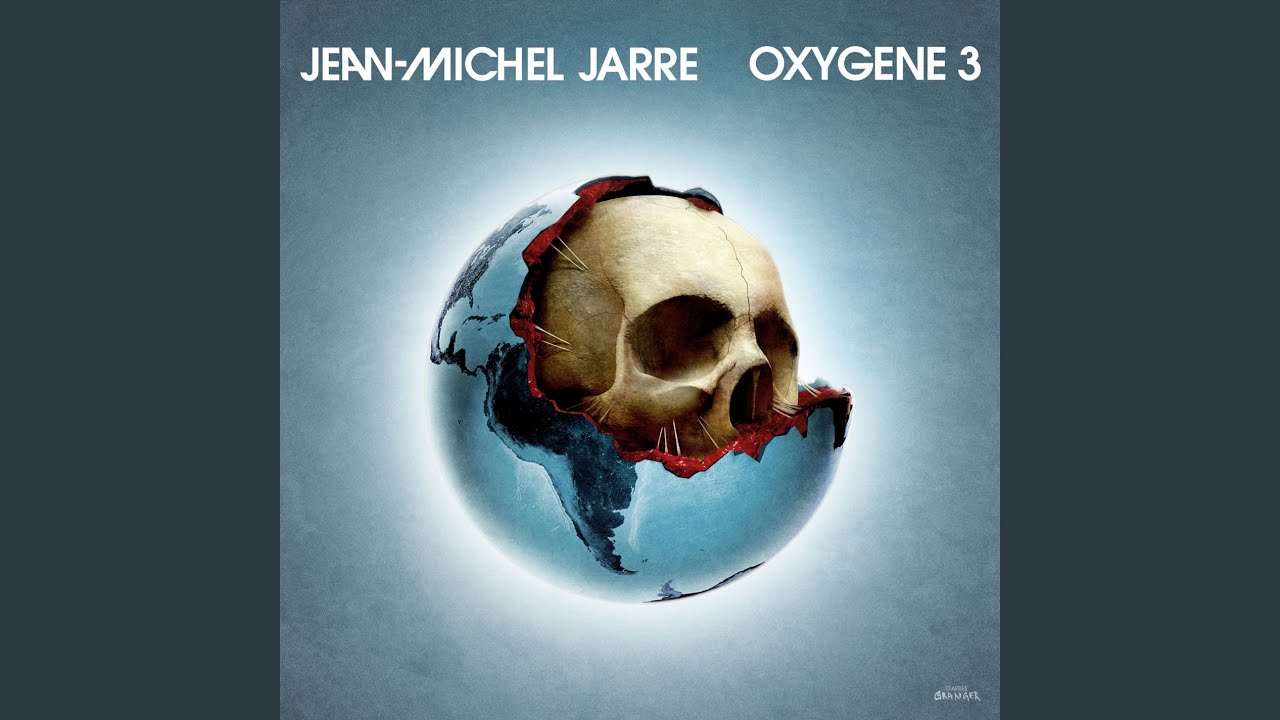

A further parallel is provided by artist Michel Granger, whose famous earth-skull design became Oxygène’s visual signifier. Oxygène 3 essentially takes the same image, this time in profile, and deepens its tone in a way that suggests something altogether more ominous.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I made the first album back in the days of vinyl, when we were always thinking about sides one and two. The other characteristic of Oxygène is that it has sunny melodies but it’s also quite dark, like the cover artwork. I decided it would be fun to take this idea but do it slightly differently. So I asked Michel to twist the cover to a certain degree on Oxygène 3. Then I thought, ‘Why not make side one dark, then side two brighter or more melodic?’ It really started from there.”

It should come as no surprise, then, to discover that Oxygène 3 forgoes the thumping techno and dense beats that gave Electronica a pulse. Instead, it’s a thoroughly modish return to the kind of cosmic fantasia that defined the original Oxygène – all radiant melodies and artful layers of synthetic sound.

“I’d already been working on electronic music for 10 years by the time I recorded Oxygène,” says Jarre, reflecting on the genesis of the album, recorded in a makeshift studio at home in Paris in 1976. “I was earning a living by doing other things and producing French rock singers. But I was obsessed with this idea of creating a bridge between experimentation and pop melody. I liked this kind of challenge, playing around with sound design and integrating melodies.

Stockhausen was totally crazy… he considered himself to be made of sound, biologically

“When I did Oxygène I had no idea that it would be successful. It was rejected by all the record companies I sent it to. In the end, a small label [Les Disques Motors] took it. Then Radio One played the album in its entirety during the first week it came out. They did that very rarely; that’s what started the whole thing.”

The notion of combining experimental music with more accessible textures can be traced back to Jarre’s teenage years with avant-rockers The Dustbins. By 1968, he’d dispensed with conventional instruments almost completely, playing around with tape loops and other electronic gear.

“The main difference with electronic music is that you create music in terms of sound, not just notes,” he says. “It’s something else entirely. When I was a teenager I always liked processing my guitar or organ or whatever, playing the tape backwards and changing the speed. Then the drummer in my band said: ‘You should meet with these crazy guys who are working in French public radio. They’re doing the same kinds of things as you, and they have labs.’”

Intrigued, in 1969 the 21-year-old Jarre joined the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, led by noted composer and musicologist Pierre Schaeffer. Originally founded at the French Radio Institution, GRM had been active since around the early 50s. Schaeffer invented the phrase ‘musique concrète’ and, among other things, helped to pioneer sampling.

“When I first went there, I was immediately seduced by what they were doing,” Jarre recalls. “Electronic music owes a lot to public radio stations – the BBC radiophonic laboratory, the German lab where Stockhausen was working and, of course, the one in Paris. I stayed for three years with Pierre Schaeffer and I also went to Cologne to work with Stockhausen. He was totally crazy, but a real genius. He considered himself to be made of sound, biologically, so he had a kind of surrealistic approach. Crazy, but realistic at the same time. It was very interesting.”

As the 70s dawned, the advent of new technology opened up an index of possibilities for Jarre and other electronic composers. The Moog synth was starting to gain traction in the States, but its hefty price tag meant only a select few could afford one.

Arthur C Clarke would tell me: ‘You know, you should finish Oxygène one day’

“I started with a British-made VCS3 from EMS [Electronic Music Studios, based in London], created by a genius called Peter Zinovieff,” explains Jarre. “It was a kind of poor European version of the Moog. In those days Europe was not as rich as the States, so the sound was drier. In a sense, it was a kind of punk synthesiser – there was something very harsh and rough about it. I loved it; I still take one on stage with me today.

“I started making music at a time when we weren’t doing electronic music with synthesisers per se, but more with a bank of oscillators that we stole from radio station studios. We’d use all the technical filters that they would use to set up their broadcast system, hijacking this equipment to make music. It meant you could create, in a sense, your own instruments. The trick for anyone starting out is to create your own limitations. Then you’ll be better able to express what you have in mind.”

Imposing his own set of restrictions fed directly into Jarre’s creation of Oxygène. It’s a record around which he’s since built a remarkable legacy, be it through big-selling albums like Equinoxe and Magnetic Fields or enormous spectacles in Moscow, Egypt and – as the first Westerner to play there – China.

Much like Mike Oldfield and Tubular Bells, Oxygène occupies a special place in the Jarre mythology. “When you’ve been lucky enough to have some kind of success with your first project, it will always be part of your DNA, no matter what you do afterwards,” he says. “It’s like the first movie for Tarantino or Kubrick. For me, it’s the same with Oxygène. I love many other things that I’ve done and I’m very proud of them all, but Oxygène is something unique.”

There remains one very obvious question: is Oxygène 3 the final instalment? “I think so. I used to be quite close to Arthur C Clarke and he’d tell me: ‘You know, you should finish Oxygène one day.’ For him it was like a journey into space, except that you could come back to a different earth. He wrote about that kind of thing, so that idea was quite a common one for him. I thought a lot about that when it came to do the final song on the new album.

“Oxygène 20 is a long piece that’s quite harmonious, but with a kind of screaming state that’s not necessarily scary, but is very poignant. When you go back through the atmosphere of any planet, everything burns, then turns to ashes. This was something I wanted to express at the end of Oxygène 3. I think it’s a pretty good way to end it.”

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.