Mike Oldfield: "I used to think 'What's gone wrong with the world?'"

On the verge of his Return To Ommadawn album, Mike Oldfield talks to Prog about the importance of location, surviving hurricanes and how to avoid pop porridge

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Mike Oldfield has quietly created a catalogue so distinctive and discrete that it stands shining, alone, not just within the realms of prog, but in the world of popular music.

His 1973 debut album, Tubular Bells, the first released on Virgin Records, remains one of the most iconic in rock’s canon. Played largely just by himself, it contained two 20-minute-plus pieces of music, and was influenced more by Sibelius and John Cage than Sabbath and John Cale (whose actual tubular bells he had borrowed for the recording). Its melding of folk, classical and rock single-handedly invented several new genres of music. It made Oldfield a reluctant superstar, a role he has now played for over 40 years.

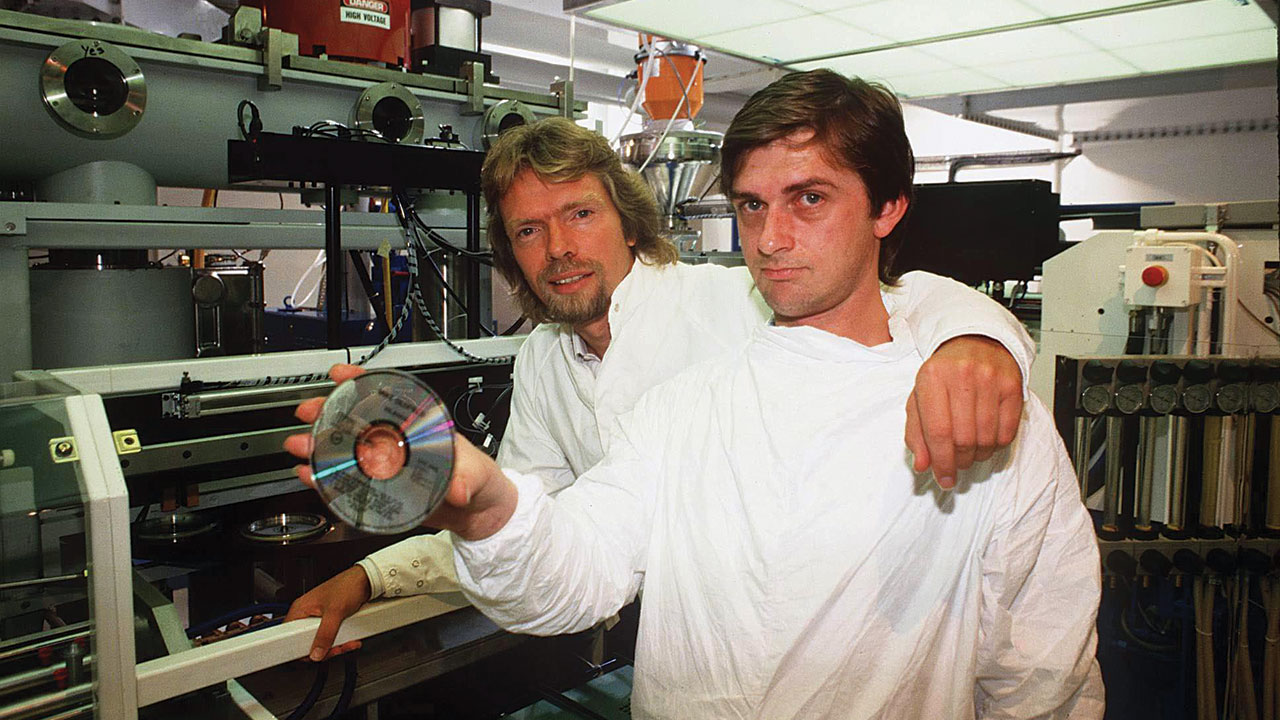

Oldfield’s story is forever entwined with that of Virgin’s founder, Richard Branson, with whom he has enjoyed a sometimes fraught but ultimately friendly relationship throughout the years. The Virgin empire expanded on the success of Oldfield.

The controversial enlightenment programme, Exegesis, in the late 70s, freed Oldfield from a lot of his introversion and set him ultimately on a course of musical experimentation that he still pursues to this day, remaining an artist that’s impossible to pigeonhole.

By the 90s, Oldfield had fallen out of step with Virgin. Long instrumental pieces were now out of favour, and every time Oldfield released one for them, Virgin suggested it should be called Tubular Bells II. Oldfield refused. But after signing to Warner, it was time to record exactly that.

Oldfield’s prolonged success chimed with the ambient house movement, and he was soon residing in Ibiza. He reflected on his time on the white island with a credit on Tubular Bells III – “Special thanks to the island and people of Ibiza” – and a simple four-word sleeve note: “Terrible, wonderful, crazy, perfect.”

When Oldfield has emerged out of his recording cocoons, it has always been for good reason: from playing at Edinburgh Castle in 1993, on London’s Horse Guards Parade in 1998, outdoors in Berlin as the new millennium dawned or, most remarkably, at Danny Boyle’s deeply affecting opening ceremony for the London Olympic Games in 2012.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In the mid-00s, Oldfield signed to Mercury – which, ironically, became Virgin EMI in 2013. A nomadic existence saw him settle in the Bahamas in 2009. After he returned to Britain for possibly the final time, to play the Olympics performance, a straightforward rock album, Man On The Rocks, followed in 2014. Featuring vocals by Luke Spiller from The Struts, it was most definitely not what people were expecting.

When Oldfield first famously retreated to the Welsh Borders in 1973 to avoid the emotional hurricane that followed Tubular Bells, he made two greatly loved albums: Hergest Ridge and Ommadawn. Ommadawn especially had resonance with Oldfield and it embraced his Celtic heritage. With just two lengthy pieces of music, Return To Ommadawn marks a return to this ‘handmade’ style of recording that he hasn’t explored for the best part of four decades.

Prog catches up with Oldfield as he’s gearing up for promotional commitments for the album – a task he greets with a happy wariness. “I’m trying to find something I haven’t already said five times already!” he says cheerfully.

You were never a huge fan of the interview process back in the 70s, were you?

I didn’t want to talk to anybody. Someone called Caroline Coon wanted desperately to interview me. I did one interview for Melody Maker and it was horrible, intrusive, rude, wanting to know ‘why’ to everything. Go away and leave me alone!

In the wake of Tubular Bells, you were also under great pressure from Virgin, so you moved as far away from London as possible to a cottage called The Beacon, in Kington on the Welsh borders…

I was just getting used to being alive, a human being, and the last thing I wanted was to pose for cameras or anything. Richard [Branson] was desperate for me to tour the States. He was on the phone non-stop: “We can get you here, we can get you there.”

He wanted me to be this star celebrity, which was absolutely the last thing I wanted. I was content being right out in nature. The Black Mountains outside my window… fantastic.

Tubular Bells’ follow-up, Hergest Ridge, topped the UK charts in 1974. Was the pressure off a little when you made the original Ommadawn in 1975?

No, the pressure was on. It was like, “Please, Mike, give us another one!” Virgin, Richard and the engineers delivered an entire top-of-the-range recording studio to my little cottage in a big lorry. They even got me a grand piano, a beautiful Steinway that fitted in the old snooker room. Richard himself carried this Farfisa organ I needed to the house.

We had concert timpani. I’d loved them since recording with Kevin Ayers at Abbey Road. I loved getting there in the morning and playing them. It was my dream to have my own set.

It was like an Aladdin’s Cave – they had recreated Abbey Road in my little cottage. The sheep were very bemused. The Neve mixing desk alone was enormous – it was a beautiful-sounding console. Once everybody had left, I remember feeling very fortunate to have so much wonderful equipment at my fingertips, and I knew how to use it.

Ommadawn retains a special magic for you, doesn’t it?

It was the first album I’d made completely on my own, engineered and produced. Gradually, through Tubular Bells and Hergest Ridge, I got into engineering. I could even do my own editing. I remember putting tape loops around the room, with tape going up the door, round the curtain rail and back through the tape machine. It was certainly one of the things that made it special.

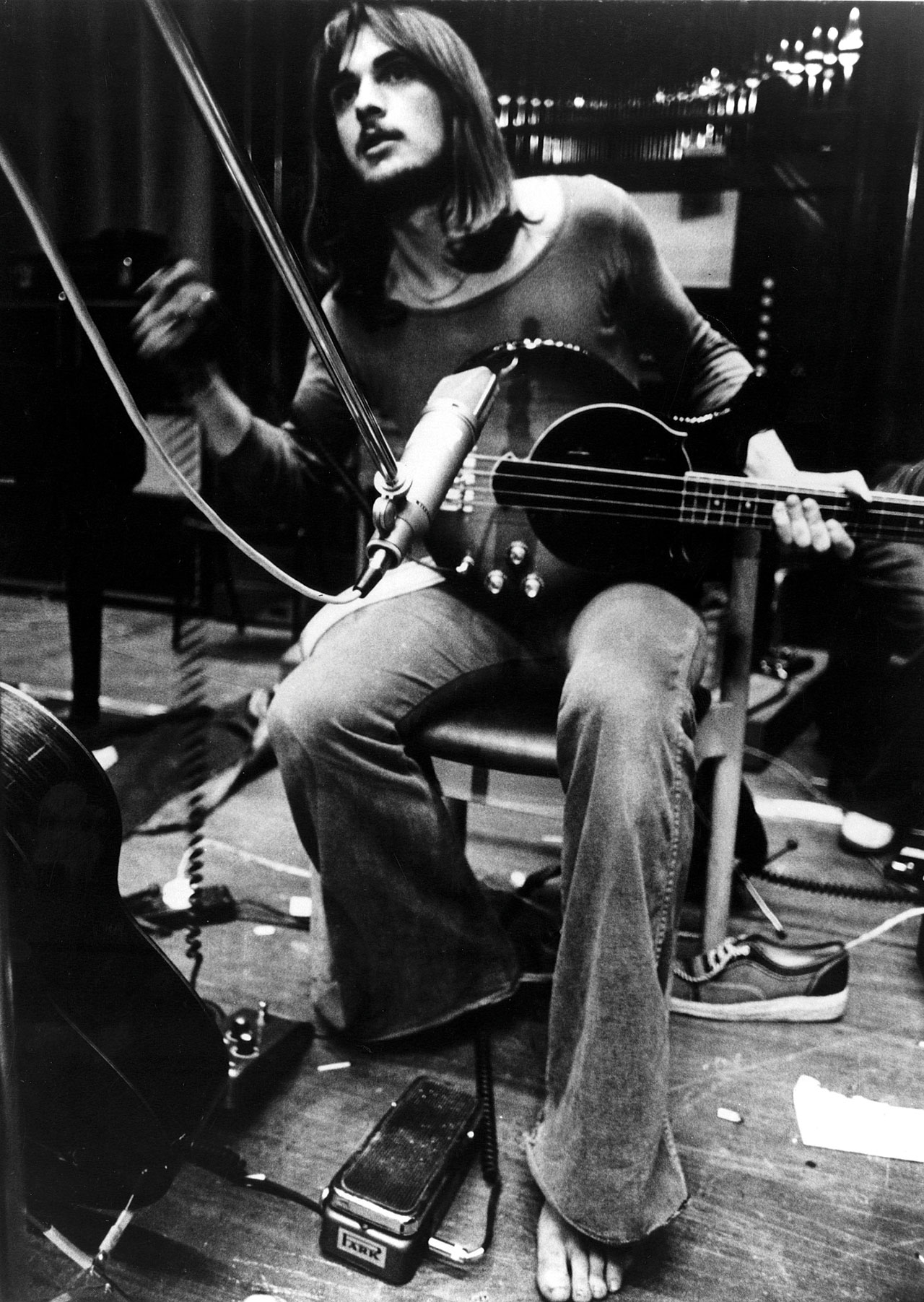

I had total freedom to work all hours of the day and night. I had beautiful microphones and guitars, all proper instruments. I didn’t have very good instruments on Tubular Bells I. It was whatever Maurice Plaquet Rental Company had in their stocks – a weird old bass guitar, a not-very-good acoustic, a very cheap Spanish – certainly not top-of-the-range instruments at all. The bass was very hard to play, with a high action, but we managed to get away with it. I was a desperate 19-year-old!

How did the melodies on Ommadawn come about?

It was a huge, interconnecting piece of musical ideas that kept recurring. I started with a Celtic harp. I wanted to make a simple folky tune with a tiny four-note phrase that had stuck in my mind. It sounded like calling someone’s name out of the ether. I had the idea for African drums. Simon Draper at Virgin happened to know [South African musical ensemble] Jabula. The session at the Manor went on for about 12 hours. The drummers all had ANC T-shirts on; they were playing without much energy. They called for a crate of beer, then another, then another. Then there was the wafting smell of strange substances coming up into the control room. Gradually, after 12 hours, they absolutely took off!

Was it true that the Edgar Broughton Band came to see you during this time?

We used to be the support band for them in the Kevin Ayers days. I especially liked their drummer, Steve [Broughton]. I asked him to do the drums on the Caveman section of Tubular Bells. They used to go around in a Range Rover because they were big macho men with beards. They turned up at The Beacon one day wanting me to play on some of their tracks [Oldfield plays on their album Bandages]. They told me about the ARP Solina string synthesiser, an electronic version of the mellotron. That was the only ‘modern’ instrument on Ommadawn.

The cover shot was by renowned photographer David Bailey. How did you get on with him?

David was very respectful – he immediately understood who I was, where I was, and what I was. He came along with Marie Helvin, who sat and talked to William Murray [ex-Kevin Ayers drummer, who worked with Oldfield at the time] while we went out into the bracken. The picture was me observing, rather than trying to get me smiling or anything; all this rubbish. I’ve since got used to doing those things – it’s part of the situation.

You left The Beacon soon after, didn’t you?

I moved house to Througham Slad in Gloucestershire. It took a couple of years to set up a recording studio there. I laid all my kit out in the stables for the pictures in the Boxed set. I got into big trouble with the locals, who were all into hunting. [Affects an upper-class British accent] “How can you destroy these beautiful stables?”

There was a seismic shift in the music industry then…

I don’t know what I should have done then. I was in a pretty lost state. The punk thing happened and all I saw was this skinny guy shouting. Suddenly it was all the rage and they were calling me rude names. My record company seemed to be more interested in them than they were in me. Incantations? I’m not that sure what that was all about. I wanted to make a double album in my new studio.

Your next step led to your change of direction over the next decade of your work…

It was time for a big change. I did the Exegesis and I was reborn – all the power of the first three albums came from my state of mind. It was a huge change from being a session man in the orchestra pit of Hair, getting fired for playing too complicated, to suddenly being No.1 just about everywhere in the world.

After your prolonged worldwide success, the Olympics, and the successful AOR of Man On The Rocks, what made you decide to revisit Ommadawn?

I thought the time was right to do one long piece all in one go again. The biggest thing for me was the reliability of the software – the last thing I did with my old Logic system was the Olympics. It always used to crash and drive me crazy. The screen resolution meant you had to keep scrolling to find things.

Then these ultra-high-definition 4K screens came out, which were fantastic. I could fit a whole 20- to 30-minute piece of music onto one screen. I updated my ProTools system so it was able to handle a lot of plugs-in and tracks.

How did you record the album?

A click track is so off-putting, so I put a clockwork metronome on it, like I used to. I added bodhran to give some kind of beat, then Celtic harp. I had to have the question-and-answer Spanish guitars. I built up all the instruments I was going to use. The penny whistle took the place of the recorder. I added African table drums and used Neumann microphones that were close to the original. Lo and behold, someone has created a virtual reality Solina string machine.

I put all the elements together, like chemicals in a big Petrie dish. I didn’t try to interfere too much. Bit by bit, as I heard little tunes, it just grew.

Do you take any advice from others when you’re recording?

I sometimes ask my sons [his youngest, Eugene and Jake] what they think. One said, “Dad, why don’t you sometimes just have one instrument?” I know what he means – sometimes you get fed up with too much going on. There’s a couple of sections where there’s only one guitar.

It’s a very uplifting piece of music. Were you surprised by how positive it sounds?

I don’t know if it’s any good. The only way I can judge it is if I’m into it, totally committed to it. If I’m working on something and I get bored, I get the feeling that it can’t be very good, but with this, it sort of appeared out of nowhere. I know it’s really working when I’m playing something and I’m not there – it’s all happening and I’m out of my body observing myself, automatically channelling something.

Does the isolation of recording in the Bahamas remind you of being back in The Beacon?

Definitely – it’s like The Beacon teleported to the Bahamas. Instead of sheep all round, I’ve got lizards and hummingbirds, and instead of the Welsh hills, I’ve got the beautiful ocean, but there’s definitely a Beacon-ish feeling to the place. Here I can see and Skype anybody, do direct recording sessions anywhere in the world from here.

There’s also a dark side to paradise – the hurricanes. You were particularly affected by 2016’s Matthew, weren’t you?

We were in total darkness and I was praying the generator would start. We all cheered when it came on. I learned a lot about generators in that time. The other big thing is to have water – luckily we have our own well.

The house is about 50 feet above the sea. Matthew destroyed the dock completely. Irene [the 2011 hurricane that inspired a song on Man On The Rocks]was much bigger, but Matthew hit us directly.

A few years before the house was connected to the main cable internet, I found I could get a direct satellite service, which is pretty slow – a bit like dial-up used to be. I kept that system for emergencies.

Virgin were desperate for [the album], so as the internet and the power were off for three weeks, I sent it from my dish. As I went to bed, I pressed ‘send’. When I came back in the morning, it was still grinding. After 15 hours, it finally said ‘sent’. It’s probably the only album in the history of popular music to be delivered this way!

It’s nice to hear you back among your instruments.

Return To Ommadawn was such a joy to make, perhaps I’ll make another one! I love being surrounded by all these acoustic instruments again. It was so lovely to do. I’ve got the hang of it now. The idea of quantizing, making everything perfect, I’m allergic to it now. Which is crazy, as I’d spent years and years perfecting that kind of computer music on things like Light + Shade, but you’ve got to try everything, haven’t you?

Are you pleased that there seems to be a healthy appetite for prog rock again?

I used to look in the window of the music shop when I was playing the folk clubs and there’d be all these adverts: “Progressive musician looking for bands.” It was really the in thing. Then the skinny guy shouting crept about the music industry for some bizarre reason and everybody thought, “This is wonderful.” I used to think, “What’s gone wrong with the world?”

For prog to come back again, it’s right. What is wrong with progress, which is the meaning of the word?

Will you be revisiting any more of your back catalogue?

I’m working on Tubular Bells IV – it makes sense that there are four sides to the box. After all these years, I think I’ve finally solved the Tubular Bells sequence problem. That’s my big project.

Do you take time to listen to current popular music?

When I come across music on TV or on the radio, the production is just too perfect. There’s a movement globally towards individuality – for example, with Brexit and Trump. People sometimes don’t want to be part of a global community all living together. Production techniques are the same. Artists are different, but they’re all using the same sound – everything is perfect. It’s put through the brick squasher so it’s got no dynamic and it’s perfectly in tune. It’s like taking all the food in the world and condensing it all into porridge. It may be good to eat, but you need the bad as well; you need the imperfection.

Which is why I purposely left all the imperfections in Return To Ommadawn, just like they were in the original one. If I make a sniff because I’m putting the emotion into a note, it’s left in.

Do you think people can be steered away from stirring this porridge?

I hope real players will start learning and experimenting with music. It’s so easy to make music now that sounds as good as any. AI [artificial intelligence] music creation software will be the next big thing – give it two or three notes and it will make this incredible thing, all part of the perfect music mulch that everybody eats. You have these fantastic synthesisers now where you press a button and it’s instantly fireworks, but it’s just a preset that a whole floor of programmers somewhere in Japan spent a whole month working on and the end user just has to tap one note. To the uninitiated, it seems like magic. You have to convince young people you can do it yourself – you don’t just have to press a few buttons. There is an alternative, and Return To Ommadawn is an example.

We’re speaking at the very beginning of December and we’ve started hearing that record in supermarkets again. It’s almost like just after Noddy Holder shouts, the recorder and acoustic come out!

In Dulci Jubilo?! It’s funny that it’s seasonal. For Halloween it’s Tubular Bells, and for Christmas it’s In Dulci Jubilo!

Return To Ommadawn is out on January 20. For more information, see www.mikeoldfieldofficial.com.

Mike Oldfield - Return To Ommadawn album review

Mike Oldfield talks Tubular Bells, the dark side and getting his mojo back

Daryl Easlea has contributed to Prog since its first edition, and has written cover features on Pink Floyd, Genesis, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel and Gentle Giant. After 20 years in music retail, when Daryl worked full-time at Record Collector, his broad tastes and knowledge led to him being deemed a ‘generalist.’ DJ, compere, and consultant to record companies, his books explore prog, populist African-American music and pop eccentrics. Currently writing Whatever Happened To Slade?, Daryl broadcasts Easlea Like A Sunday Morning on Ship Full Of Bombs, can be seen on Channel 5 talking about pop and hosts the M Means Music podcast.