Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“I’ve had it with your sweet-talking politicians, all you want to do is go and steal the world, try to tell us that you’re here for all the people, when inside you’re really out to screw us all,” says Jon Anderson with some gusto. He’s reciting the lyrics from Go Screw Yourself, a song that would be released online a few days after Prog’s interview. His anger at the current political situation is palpable. As he talks, his words are interspersed with rueful, heavy sighs at what he sees as the terminal stupidity and wilful deceit of a political class lining its own pockets at the expense of people and the planet. “They’re like children playing around: ‘It’s my ball. No, it’s my ball.’ That’s all it is. These politicians drive me crazy because they’ve no sense of compassion or what’s really going on. It’s about time we all woke up, seriously.”

The smoke-filled skies above his California home and elsewhere that have dominated his home state following this year’s spate of forest fires only adds fuel to Anderson’s ire and exasperation. “The most important thing at this time in our world is Mother Earth and saving it for our children’s children,” he says. “There’s a bigger world out there there’s got to be taken care of rather than greedy politicians playing ‘who’s got the ball.’”

Faced with the daily doom and gloom of newspaper headlines, Anderson nevertheless remains optimistic about the possibility of a substantial shift in public opinion. At his core, he believes that good will prevail, that despite the travails and challenges, what’s best of us will survive. Anderson is nothing if not a survivor. “I always have a very positive feeling about the development of a state of mind and the consciousness of the planet, by which I mean everybody is going to raise their consciousness after this terrible virus,” he says referencing the implacable rise of Covid-19, fully aware that as a chronic asthmatic, a condition that nearly killed him in 2008, he’s especially vulnerable. “They’re going wake up a bit and realise that looking after the planet, looking after this beautiful home of ours is what we should be doing.”

The notion that a song could help crystallise a thought into a popular cause or movement may seem fanciful to some but to Anderson, it’s a given. “One song will come along and people will hear it and say, ‘Shit! That’s correct, these people have got to wake up and dream rather than wake up and look for money.’ John Lennon said it: ‘Make love not war, give peace a chance.’”

This isn’t the first time Anderson has invoked Lennon’s anti-war/pro-compassion message either. In 1971, the rousing chorus of Give Peace A Chance was discretely co-opted into the backing of I’ve Seen All Good People from The Yes Album.

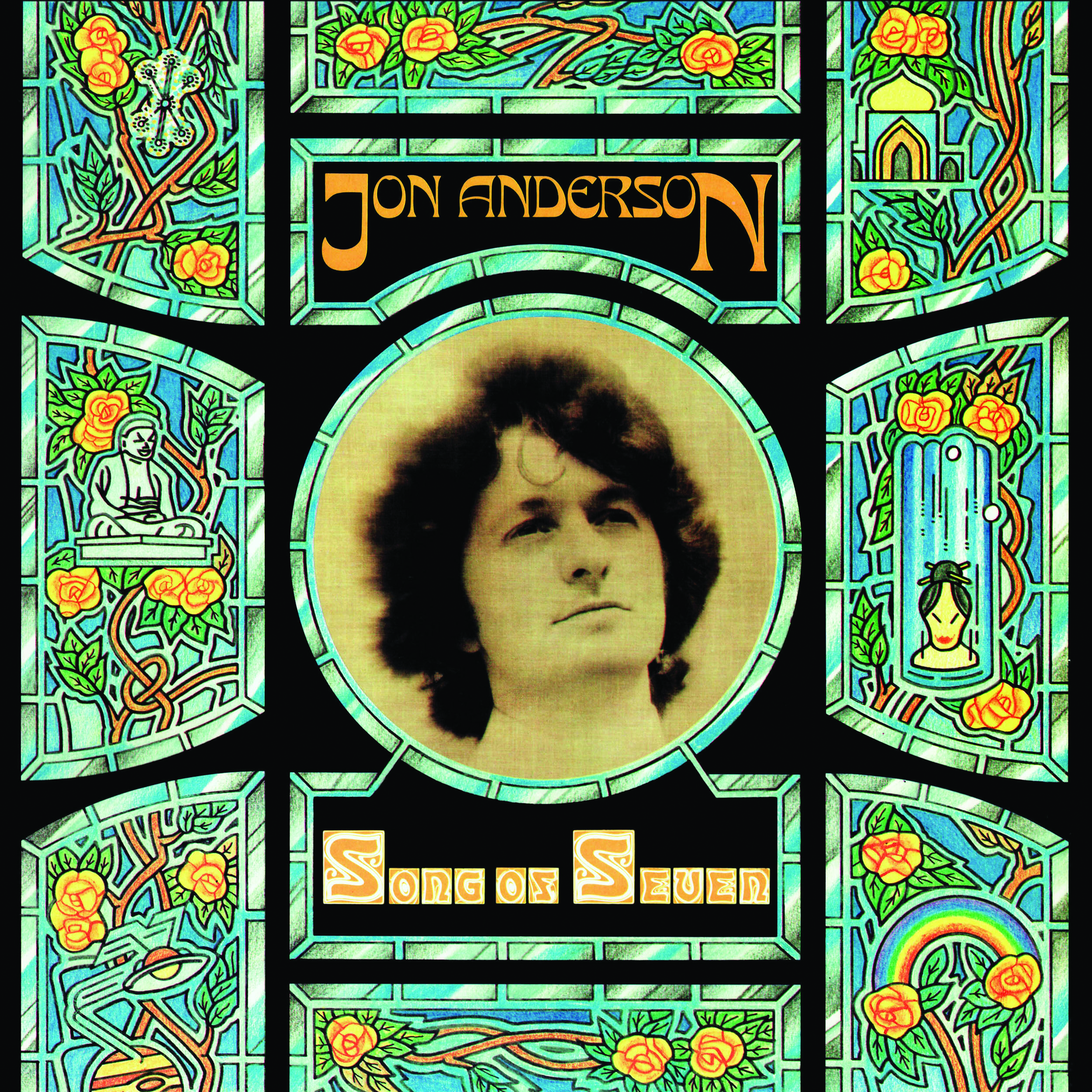

Although the views expressed in Go Screw Yourself are explicitly unambiguous, Anderson’s form in that department hasn’t always been so crystal clear. Over the decades the precise meaning of much of his work has been famously obscure and oblique, usually resisting the usual kinds of literary and literal analysis from sceptical critics and hardcore fans alike. Nevertheless, Anderson insists that the mundane, worldly realities of current affairs have always found their way into his music, a subtle influence that has on occasion directly inspired a lyrical approach. A case in point, he argues, would be elements of For You For Me from Song Of Seven, originally released in 1980 and, now in 2020 it’s the subject of a remastered and expanded reissue. “I was actually listening to it last week just to check on what I was thinking in those days, and it’s pretty political, it’s an interesting song,” he says enthusiastically.

It’s not possible to discuss the creation of his second solo album without understanding the events surrounding the making of Yes’ final studio album of the decade, Tormato. The tracks Some Are Born, Hear It, Days and Everybody Loves You, which all appear on Song Of Seven, were written and recorded during the Tormato sessions in Paris. They were also roundly rejected for inclusion on the final record, indicative of the widening rift between Steve Howe, Chris Squire and Alan White in one corner of the studio and Rick Wakeman and Anderson in the other. Looking back, Anderson sees a couple of conflicting factors at play during that time. “I think that one of the things about being in a band is that when you’re surrounded by people who just want to push you, push you, and push you to make money,” he pauses with a degree of resentment in his voice, gathering his thoughts. “I mean, that’s okay… but there are times when creativity is suppressed by the energy to make a hit record, and that was really what was going on around that time.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

There was a distinct pressure to come up with something as commercially successful as their 1977 single Wonderous Stories, which was a surprise hit for Yes. While Don’t Kill The Whale from Tormato fulfilled that role, gaining access to the UK Singles Chart where it reached No.36, both songs were, in some ways, hits by accident rather than design. “When I’m under that pressure I just back off, because honestly, I haven’t got the natural gift to write pop songs like Elton John and Bernie Taupin and people like that who just naturally do it as part of their life, you know? I’m a different sort of musician. So when all that was going on I wasn’t happy.”

At their best he says that Yes were happiest when left to make music on their own terms: “But outside influences that have been brought in over the years haven’t helped most of the time.” He’s referring to the arrival of producer Roy Thomas Baker, ushered in by Yes’ management during the preparatory sessions for Tormato. “I just needed somebody who was committed to work well and get in the studio in the early morning. We started off working in Paris I think and he spent more time in the clubs with a couple of guys from the band. He liked clubbing it. So he was really one of the reasons why it all broke apart. Me and Rick and Alan and Steve would be sitting around waiting for Chris and this producer dude to come along. It was always like waiting for Christmas to come, you know?”

At the end of a lucrative tour, Anderson had had enough and quit Yes in February 1980.

As the 70s gave way to a new decade, and the politics of polarisation, personified by the elections of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, wrought seismic changes in society, Anderson found himself in an unusual position. He was now being described as an ex-member of Yes, his musical home since the band’s formation in 1968. Included on the group’s 1969 Atlantic Records debut was one of his songs, Survival, and some of its lyrics now seemed especially apt in describing Anderson’s situation a little over 10 years later: ‘The beginning of a shape of things to come/That starts the run/Life has begun/Survival.’

As Anderson found out, surviving life as a solo artist in the 1980s brought both opportunities and challenges. “Before Song Of Seven I’d made an album for Virgin Records. I got on well with Richard Branson. He had a record store around the corner from the Marquee Club, so I’d pop in there every day, chatting and listening to records. He was always very sweet. After he’d started the Virgin label he talked about me working on some music and offered to give me the money to make the album. He said, ‘If we don’t like it, you have got to pay me back.’ I said, ‘Okay.’”

Anderson laughs out loud at the memory of the encounter, recalling that the finished music he presented involved one side of an album based on the life of Marc Chagall, the Russian-French artist lauded for the vivid luminosity of his painting and in particular his stained-glass windows that were installed in various European churches and cathedrals. The other side of the record was about the faerie kingdom. “I really got into the subject in the 70s, reading books about the inter-dimensional beings that surround us all,” he explains. Only Jon Anderson could mention an album themed around the existence of inter-dimensional beings in such a matter-of-fact tone and not seem, well, away with the fairies. He does laugh, however, when relating Virgin’s reaction to the offering.

“They’d sent a couple of young guys around, 20 years old each. They looked more like punks really.” Needless to say, they were less than impressed with what they heard. “One minute you think you’re doing really important music and then someone says, ‘You gotta give us the money back.’”

That kind of rejection might have been regarded as a humiliating setback for some musicians used to performing in front of hundreds of thousands of people. It’s impossible to say how much of an impact it had on Anderson’s psyche at the time considering it came quickly on the heels of his departure from the band he’d dedicated a significant portion of his adult life to. Now, so far away from the events themselves, Anderson is sanguine about it all. “Life does things like that. So I said, ‘Okay, let’s get on with life.’”

The vocalist is nothing if not resilient; the result was a working group he dubbed The New Life Band augmented by special guests. In some respects Virgin declining what would’ve been his first post-Yes project acted as a kind of artistic palate cleanser and he signed a deal with his old label, Atlantic Records, clearing the decks for an earthier R&B style approach. Perhaps mindful of budgetary implications, he recorded Song Of Seven at his home in London just as he had done with 1976’s Olias Of Sunhillow. However, the musical style and language couldn’t have been more different. Anderson indicates he went into the session with one aim: to have as much fun as possible.

“When I was making the album, I was just having fun rather than feeling any pressure. I wasn’t thinking about whether or not this album was going to make me a superstar. I just got people to come by and just have fun, people like keyboard player Ronnie Leahy and a couple of other great musicians.”

One of those “great musicians” was bassist Jack Bruce, best known for his work in Cream. “I had a friend who knew him; he came round to the house and recorded Heart Of The Matter. A jaunty, pop-orientated co-write with Leahy is far from the cosmic, ethereal writing with which he’s associated.

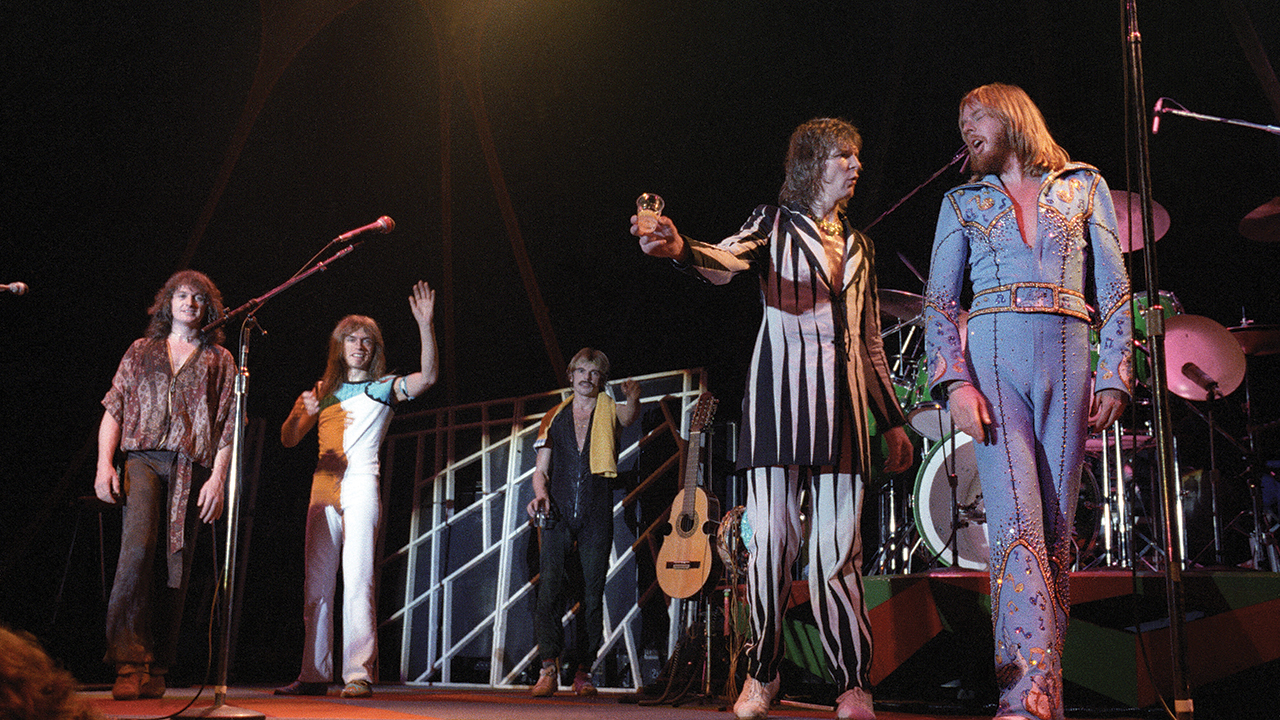

The sessions also knitted together two different timelines, with Anderson reminiscing about Yes’ appearance at the Royal Albert Hall as one of the support acts at Cream’s legendary farewell performance in 1968, a mere three months after Yes’ very first live show. “That was truly an amazing, amazing experience to watch Cream on the stage that night. It was unbelievable. These guys were the real stuff. We’d just started a band and we felt very small in comparison. We thought we’d just get onstage and sing a couple of songs. When we set up on the stage, it was so big, we set up our gear to the right and we were all like, ‘Let’s just get through the songs playing in front of 6,000 people.’ [Laughs.] I remember saying hi to Jack at the gig at the Albert Hall and I think I bumped into him a couple of times when I was working in the bar at La Chasse club above the Marquee. He was always very nice, very sweet, saying, ‘How you doing, Jon?’ I was like, ‘Wow, Jack Bruce, one of the great singers and bass players of all time, is speaking to me!’”

Saxophonist and bandleader Johnny Dankworth, a veteran of the UK jazz scene, also dropped by to help out. He contributes a fluid sax to the lilting Don’t Forget (Nostalgia). Says Anderson, “I got to meet Johnny through his wife, the singer Cleo Laine. I knew her from way, way back at some record company reception. I had to say hello. She was such a character, we got on very well.”

Anderson recalls being invited to a party at the Dankworths’, where he ended up dancing briefly with another guest, Princess Margaret. He guffaws at the memory. “Yes, but the funny thing is that the London scene was something that I never really connected to, you know the whole celebrity thing. I never got into that. Mostly it was just friends who knew other people and we’d get talking about music and I’d tell them that I was working on a project and invite them to come over and play.”

Unlike his previous experience with Yes, this time around there was nobody from Atlantic asking for a hit. “You know, it’s funny, you make records, and then the A&R guy will call you up and say, ‘Well, Jon, we just listened to the album and we don’t hear a single.’ And then that’s when I put the phone down. Actually they thought that Some Are Born was going to be a good one and there was another one that I felt was pretty good, For You, For Me. The opposite of that was Take Your Time which was a lovely, lovely sort of a sweet song.”

If much of the album grew in a poppier, feel-good direction, the title track, Song Of Seven sounds like it could have easily sat within the 70s Yes setlist. It picks through a discursive melody meandering in a largely pastoral setting in which Clem Clempson’s guitar breaks flourish and adds a dramatic grandeur. “Clem is such a great guy, a really special player,” says Anderson. “I worked with him again on Animation in 1982 and he was in the touring band then and later on when I did the demos for Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe.”

The 2020 reissue of Song Of Seven, expanded to include the US single edits of Some Are Born and Heart Of The Matter, both previously unreleased on CD, shows an album that stands up well. “Sometimes you come back to something you did in the past and say, ‘Hey, this is pretty good,” says Anderson with evident pride.

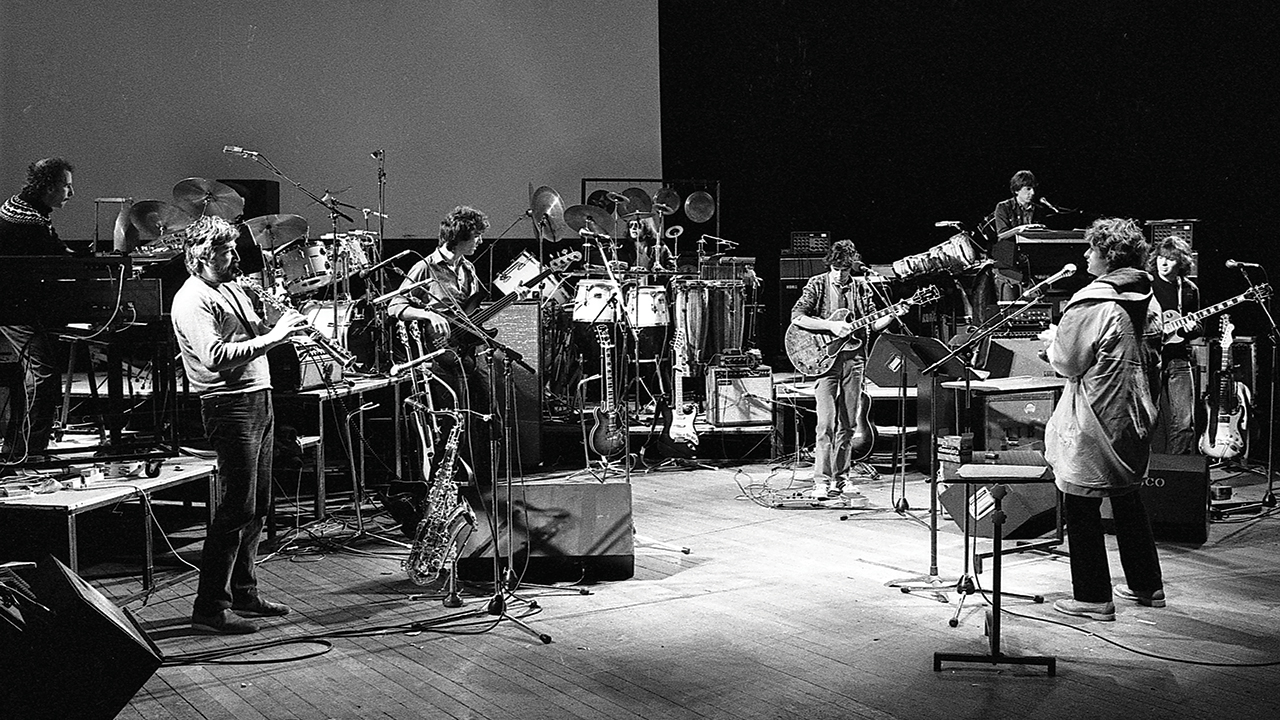

Originally released in November 1980, Song Of Seven entered the lower reaches of the Billboard charts in the US and the UK Album Chart. Although lacking the kind of momentum that a new Yes record would have garnered, it was a key step to Anderson’s development and survival as an artist. Part of that mission included the singer going out on the road with Dick Morrissey (sax and flute), Barry De Souza (drums), Morris Pert (drums and percussion), John Giblin (bass), Lee Davidson and Jo Partridge (guitars), and Ronnie Leahy and Chris Rainbow on keyboards under the collective title of The New Life Band. “It was really fantastic,” Anderson remembers. “I’ve found, over the years, that if you get the right bunch of people together in a band that’s in harmony with what you want to do, it’s like sailing in a boat; it’s so easy. I’ve only done it, maybe four or five times in my career where I get together five or six people and you can sense when they want to really engage.”

While Anderson is complimentary about the ability and skills of his colleagues there was a moment during the rehearsals for the tour that perfectly illustrates his role as a creative catalyst, taking one element, seemingly abstract and diverse, to energise or invigorate the other. As the band rehearsed for a section of the show that would essentially be a jam session without Anderson onstage, Anderson noted that although what they were playing was ostensibly good, it lacked shape. Sensing that it wasn’t really taking off, Anderson came up with a novel suggestion.

“I said to Ronnie Leahy that he could learn the three main melody lines from Petrushka by Stravinsky. He was like, ‘Okay, Jon’ and was really unsure but they did,” says Anderson with a laugh.

Whatever limitations he might have as an instrumentalist, there’s no denying Anderson’s remarkable ability as a conceptualist capable of seeing what needs to be done in order to take the music from the ordinary to the next level.

“The idea was, we got [sings one of the three main themes from Petrushka] into the bass solo. It helped them get from point A to point B: from the bass solo, then the guitar solo, then the sax solo. It worked and I remember when we did the show at the Royal Albert Hall [in 1980], that was really fun. It was really good hearing a band doing Stravinsky that way.”

Whenever one speaks to Jon Anderson he’s always working on a range of new ideas and has lots of different projects on the go. Maybe he’s dusting off something he started working on a few years before or putting the finishing touches to something else that’s in the pipeline such as Go Screw Yourself, or maybe even a reggae-infused ukulele tune written while on holiday five years ago that he thinks might do nicely as a Christmas song this year. His enthusiasm is nothing new though as even when he was working on Song Of Seven he was also recording material for 1982’s Animation. “I was thinking about the next four or five years of my life, musically and it’s what I’m doing now. I’m working on about four albums now especially these last six months being at home. It’s good because you get on with your vision for the next five years or 10 years of your work.”

A glance at his solo discography shows him, then as much as now, keen to collaborate with a diverse range of players: Mike Oldfield, Béla Fleck, and Rick Wakeman all crop up. There was even an attempt to form a new band with Wakeman and Keith Emerson. Anderson recalls: “I was actually staying in Amsterdam at the time and I started thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be great: me and two keyboard players?’ You see different colours, different textures.” It didn’t happen, of course. Emerson was keen but he says Wakeman prevaricated. “The energy could have been amazing. Sometimes people just don’t see the potential.”

Seeing potential is something that Anderson has always been good at. In 1973, after hearing a copy of L’Apocalypse Des Animaux by Vangelis and connecting with the languid soundscapes of Creation Du Monde in particular, Anderson was convinced the ex-Aphrodite’s Child keyboard player would be perfect to replace a departing Rick Wakeman after the Tales From Topographic Oceans tour. “We brought him to London but he didn’t really work in the band. He’s a one-man vehicle, you know?” Although that encounter didn’t work out the pair became firm friends and began an extremely fruitful partnership.

Their first album together, Short Stories, was recorded in London in February 1979, before the split with Yes. Released at the beginning of 1980, it hit No.4 in the UK Album Chart while I Hear You Now found itself at No.8 in the Top 40, with Song Of Seven bringing his first year outside of Yes to a rather satisfying conclusion Anderson looked to be in good shape as a solo artist. The following year found Anderson in the company of Vangelis once again to record The Friends Of Mr Cairo, which spawned I’ll Find My Way Home as a single, resulting in a surprise hit requiring the duo to lip-sync in front of a studio audience, swaying from side to side. The video on YouTube shows Anderson grinning and being the effortless showman, clearly very comfortable. Vangelis, by comparison, looks rather awkward. Anderson laughs at the memory of it. “The funniest thing was Vangelis said he didn’t want to be a pop star. ‘I’m a real musician, Jon.’ I said, ‘Don’t worry, Vangelis, it’ll sell more records.’” Joking aside, he says the partnership with Vangelis taught him so much about himself as an artist and how he worked. “I was learning how to be spontaneous lyrically. Watching him work taught me so much, musically speaking. I remember he was recording in Paris what was going to be The Friends Of Mr Cairo. He was actually playing a groove as I happened to walk in and I sang State Of Independence, the whole thing, spontaneously without thinking. The whole shape of the song in one long take.”

As someone who didn’t like being under pressure to write hits and wasn’t certain how things would work out beyond Yes, Anderson was doing okay. More than okay, in fact. When American producer Quincy Jones was given a copy of The Friends Of Mr Cairo he saw it as a perfect vehicle for Donna Summer. The hits, as they say, kept rolling in. From the outside, things looked good. Anderson was in control of his destiny. His third solo album Animation did well enough and with still more appearances on other artist’s albums and his ongoing partnership with Vangelis, it was something of a surprise to see him return to the Yes camp. “I was actually living in the south of France working on projects and very invested in creating music, but I missed the whole excitement of touring. I’d been on tour with Animation in America with some really good people but it just felt like hard work, the gigs not the band. It was not what I was interested in doing.”

Feeling like he was back in the 70s when Yes were slogging around the support slots, the experience gave him pause for thought. “I was thinking, ‘What am I doing this for?’”

When Chris Squire invited Anderson up to come and listen to the material he, Alan White, and Trevor Rabin had been working on, he was happy to do so. When, after a short time, Cinema reconvened as the new Yes, Anderson had no hesitation in signing up. “I realised I missed being in Yes when it was really looked after properly, when it was really taken care of and towards the end of the 70s, after Tormato, it wasn’t. It’s funny, of course, because back then, management wanted us to make more commercial music, and here we were with 90125, the single most commercial album we ever made.” The rest, as they say…

With hindsight and a generous dollop of pragmatism on both sides of the fence, it was perhaps inevitable that Anderson would return to the Yes fold for 1983’s 90125, reconvening what was a difficult on-off relationship with the band. Prior to Tormato, he was very much a catalyst and agent provocateur. After 90125 the balance of power had subtly shifted and would continue to do so right up until 2009 following his hospitalisation after a severe asthma attack. “They decided to move on without me, which is their choice.” His survival instincts kicked in once again and after convalescing he’s returned just as busy as he was in the 80s, with a series of collaborations and releases, including the recent 1000 Hands, which he regards as essentially being Yes music in all but name.

Having always included material from Yes in his solo shows and more recently with Anderson, Rabin & Wakeman, he sees himself as the true custodian of the band’s progressive spirit. “For me, I am Yes. It’s never left me,” he says. Of the current incarnation of Yes, he admits to having difficulties with their new material. “I haven’t heard anything that hits me and says, ‘Oh boy, I’m so happy they’ve evolved.’ It’s really great to hear them do the classic songs and Jon Davison’s singing well and everything but it’s a far cry from what it would be if I was there creating Yes music.”

Being in Yes was always a difficult proposition: great when it works but when it doesn’t things can get really bad. Knowing all of this, would he return if the opportunity presented itself? “I’ve said before that I’d love to do it as a final hurrah for the fans and go on a very special tour. I had a dream a month or so ago that I was opening the show solo, playing my acoustic guitar, singing a couple of songs. Then, Steve brings on his band and they play a couple of songs. Then I come back and do a couple more acoustic songs solo. After that, Rick and Trevor and all the others come on and play. There’d be about 20 of us on the stage all playing Close To The Edge. I started to see and visualise the whole piece, both musically and visually, it was kind of amazing.”

Dreams and visualisation, and perhaps, hopes and wishes, aside, having just celebrated his 76th birthday readers might expect him to be taking things easy. Not a bit of it, he says. “I’ve been actually writing large-scale pieces of music this last three or four months, which is, in a way, the recurring theme in my life.”

And Prog can’t wait to hear them.

This article originally appeared in issue 115 of Prog Magazine.

Sid's feature articles and reviews have appeared in numerous publications including Prog, Classic Rock, Record Collector, Q, Mojo and Uncut. A full-time freelance writer with hundreds of sleevenotes and essays for both indie and major record labels to his credit, his book, In The Court Of King Crimson, an acclaimed biography of King Crimson, was substantially revised and expanded in 2019 to coincide with the band’s 50th Anniversary. Alongside appearances on radio and TV, he has lectured on jazz and progressive music in the UK and Europe.

A resident of Whitley Bay in north-east England, he spends far too much time posting photographs of LPs he's listening to on Twitter and Facebook.