The story of Fairport Convention's Full House

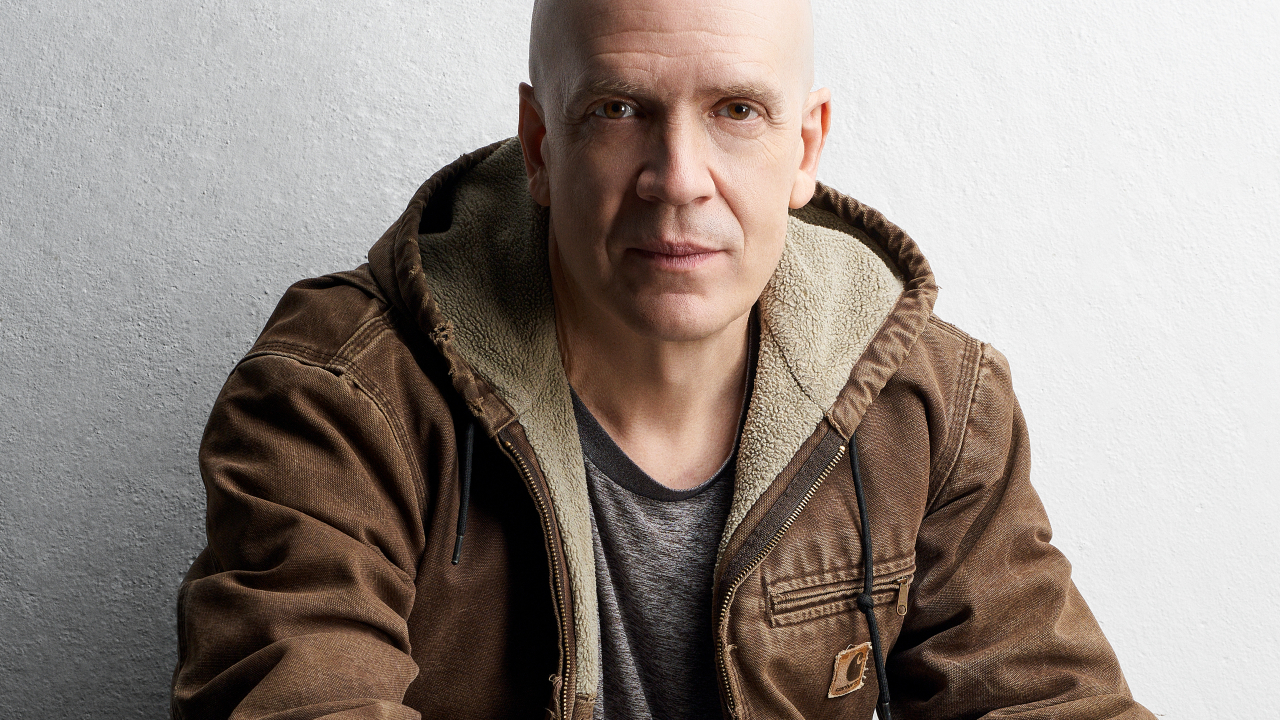

The Fairports recall the making of 1970's Full House, the band's first album without founding member Ashley Hutchings and with new boy Dave Pegg

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“On my 22nd birthday – November 2, 1969 – I went to Mothers club in Birmingham with my ex-wife Christine to see Fairport Convention,” says the group’s current bassist Dave Pegg. “I had never seen them before but I knew [violinist] Dave Swarbrick from his work with Martin Carthy and I had played with him in the Ian Campbell Group.

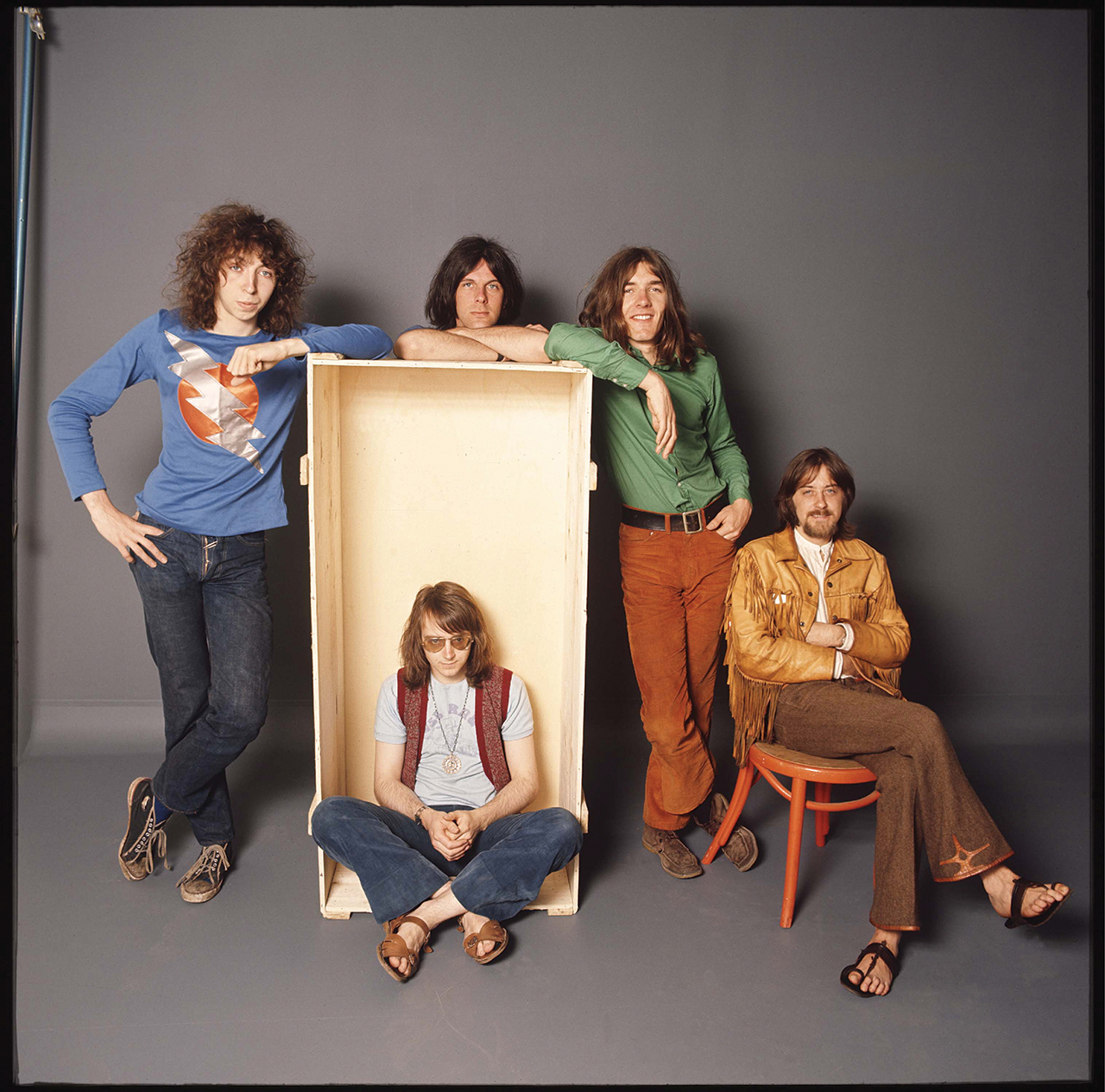

“It was a new approach to traditional music,” he recalls. “It was such a great band: the interplay between [guitarist] Richard Thompson and Swarbrick instrumentally, and of course Sandy Denny’s singing and the great rhythm section of [drummer] Dave Mattacks, [rhythm guitarist] Simon Nicol and [bassist] Ashley Hutchings. I was blown away and said to Christine, ‘I would love to join that band.’ And bizarrely I got a call next day from Dave Swarbrick saying, ‘Ashley is leaving the band, would you come for an audition?’”

Pegg, who had played in rock bands in the Birmingham area including The Uglys with Steve Gibbons and The Way Of Life with future Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham, landed the job. The following month, Fairport released the epochal British folk rock statement Liege & Lief, but its release coincided with Sandy Denny also quitting the band.

Article continues below“It was a blow to lose them both but the mood was optimistic,” Richard Thompson recalls. “We thought it would be hard to replace Sandy, so let’s not replace her. We knew that the vocals would not be as strong, but instrumentally we were a very strong band. In the history of Fairport there had always been personnel changes. This was a big one, but our attitude was to soldier on.”

“It removed the rudder and the best part of the engine room of the Good Ship Fairport,” says Simon Nicol.“But at the same time we’d got this incredible energy coming from Dave Swarbrick. He was a born-again musician because he was a full member of a band for the first time in his life. There was a sense of, ‘I really like this and I’m really going to make it work.’ He made up for the loss of the engine room in many ways. And so we became a boy band.”

On Liege & Lief, Fairport had made the decision to incorporate more traditional British and celtic elements into their music, an approach they carried on to their next album, 1970’s Full House. Stylistically, much of this was essentially still uncharted territory. Musicians had long been playing medleys of traditional jigs and reels, but not in an electric rock band. Fairport were effectively learning on the job and were all in their early 20s, except Swarbrick who was 28, and Nicol who was still just 19.

Before he joined Fairport Convention the summer of 1969 Dave Mattacks had played in a dance band and various pop groups.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“On Liege & Lief I was very much, on an aesthetic level, the deer in the headlights. I had no idea what I was doing,” he says. “I was responding to the music around me and starting to grasp it. Then I had a huge light bulb moment when I got what the band was about, and it had a profound effect upon how I wanted to play and how I heard music. But even on Full House, I can still hear a very green drummer.”

Speaking to the four surviving members who played on that album, it’s striking how much they respect each other’s playing.

“Ashley had a very distinctive style that contributed to the early Fairport sound,” says Thompson, “but Peggy was much more funky, more solid. And it was astonishing that he started to play jigs and reels on the bass an octave or more under everybody else. That virtuosity became a part of the Fairport sound and was unveiled on Full House.”

Pegg describes Swarbrick as a “walking library of tunes” and for Full House he had put together the dazzling instrumental medley Dirty Linen, on which the bass player came into his own.

“I knew something about traditional music from having played with the Campbells,” he adds “On Dirty Linen I play the bass in unison with all the other guys and was able to keep up with them. It got me a bit of a reputation, but to be honest, the only reason I played in unison was I hadn’t got a clue what else to play on it! The Flatback Caper medley is another thing that hadn’t been done before. That was kind of proggy, with Swarb and I both playing mandolin.”

In December 1969, Fairport – in Pegg’s words – decided to “get it together in the country, like Traffic” and ended up living communally in a former pub, The Angel in Little Hadham in Hertfordshire. It was not as idyllic as that might sound. The band had visited but found it “cheerless” and “too primitive”, and didn’t want to move in, but Swarbrick had assumed it was a done deal. He got in touch saying that he had hired a removal van and was moving his wife and daughter from Milford Haven in Wales, and asked for the address of the new place, obliging them to take on the lease. A total of 13 people, including the road crew, ended up living in accommodation with one bathroom and one kitchen.

“There was a wall heater that gave you about two inches of bath water,” Thompson recalls. “The place was generally unheated and we got some storage heaters that didn’t really do anything. The cosiest place to be was in what was formerly the entertainment room. We would build big fires and rehearse and hang out in there.”

But despite these privations, Thompson and Swarbrick hit their stride as a songwriting team. “We wanted to write songs that sounded like a modern continuation of the tradition. That was very important to us,” says Thompson. “I had grown up listening to folk music, to Scottish ballads particularly, and although The Kinks and The Yardbirds seemed more important to me than a ballad from the 16th century, I had at least some preparation for it.”

Their modus operandi was that Swarbrick would come up with a tune and the two would work on it and try out different harmonies and arrangements and then Thompson would go off and write the lyrics. This approach yielded Walk Awhile, with its droll cast of characters, the hymnal single Now Be Thankful and Doctor Of Physick, whose nocturnal visits involved a particularly sinister bedside manner. But the most remarkable song on Full House is the nine-minute Sloth. Verses of sombre images in a time of war lead into an improvised instrumental section with Swarbrick and Thompson trading lines in the way that so impressed Pegg, and the band play with empathy and adventure. Its roots lay in the lengthy A Sailor’s Life on 1969’s Unhalfbricking.

“A Sailor’s Life was a very important song for Fairport because it really opened up new vistas,” says Thompson. “Pink Floyd and The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown did a lot of improvising and Fairport did as well – we were an underground band responding to traditional music.”

Fairport had been rehearsing instrumentally, but with a gig coming up at the Hampstead Country Club at the end of January, there was a matter of who was going to sing. Pegg even remembers them drawing straws as part of the process.

“Swarb liked the idea of singing although he’d literally never done it before, but I think all of us were slightly reluctant,” says Thompson. He explains their approach to ensemble vocals on Sir Patrick Spens on Full House, a traditional song they had first rehearsed when Denny was in the band: “We are trading off all time. We’d do a verse here, a chorus there, two of us singing one part and the other two singing the other part.”

The recording of Full House commenced in February 1970 at Sound Techniques in Chelsea where Fairport had recorded Liege & Lief, and was again engineered by John Wood and produced by Joe Boyd.

“The band sounds better on Full House,” says Mattacks. “You can hear the top end open up. Liege & Lief is a very muted album, the antithesis of sparkling. That’s because we were very enamoured with The Band and rolled off a lot of the high frequencies to get a thicker, warmer sound. We were too naïve to realise it was actually all to do with the playing, singing and tuning, and instrument selection.

“John Wood was an unbelievably good engineer. Joe very much left the technical side up to him as he was more concerned with the aesthetic side, the larger picture.”

The vocals were recorded separately with Wood and Boyd, at Vanguard Studios in New York when Fairport Convention were on tour in the US.

“I was the baby of the band. I was still 19 so it was like a big deal for me to be in a New York recording studio, particularly at Vanguard because this was where Count Basie recorded,” says Nicol. “It was an impossibly glamorous situation. It was daunting having to sing ‘Walk awhile, walk awhile’ and hear this voice coming back and thinking, ‘God that’s me.’”

One of the highlights of the album, the grim Swarbrick/Thompson musing on punishment and justice, Poor Will And The Jolly Hangman was pulled at the 11th hour by Thompson, but has been included on more recent pressings.

“I should have just persevered and done a better vocal,” he admits. “But it’s got quite a big range and I was very self-conscious of not being strong on the high notes. It was stupid to pull the track but it’s since been restored with a better vocal on it. The album is more now as it should have been in the first place.”

The vocals were a little tentative on Full House, but the live album House Full: Live At The LA Troubadour, recorded in September 1970, highlights the boy band on formidable form and they had quickly grown into a confident vocal unit. Thompson left amicably in 1971 to concentrate on his solo career, but the group characteristically soldiered on without him.

Fairport Convention’s Full House line-up are playing the album in its entirety at this year’s Cropredy Festival in a delayed 50th anniversary celebration, with current multi-instrumentalist Chris Leslie playing Swarbrick’s parts. Prog wonders how important the album is to the group?

“It’s a very important record,” says Nicol. “I think when Peggy joined it changed so many things. Fairport before and after Peggy are two different animals.”

The bass guitarist agrees: “To me it was a life-changing album. I’m sure people will be playing it differently to the way they did 52 years ago so it won’t be identical but it’s going to be in the same order! We will do it justice. I’m really looking forward to it.”

This article originally appeared in issue 132 of Prog Magazine.

Mike Barnes is the author of Captain Beefheart - The Biography (Omnibus Press, 2011) and A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s (2020). He was a regular contributor to Select magazine and his work regularly appears in Prog, Mojo and Wire. He also plays the drums.