“Look at Kate Bush or Queen: sometimes when you don’t do the norm, that’s what changes the world a little bit” - How Midge Ure finally embraced his prog tendencies

Ultravox’s Vienna and Band Aid might have made his name but Yes, Uriah Heep and ELP figured in his musical education - even if no one noticed

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

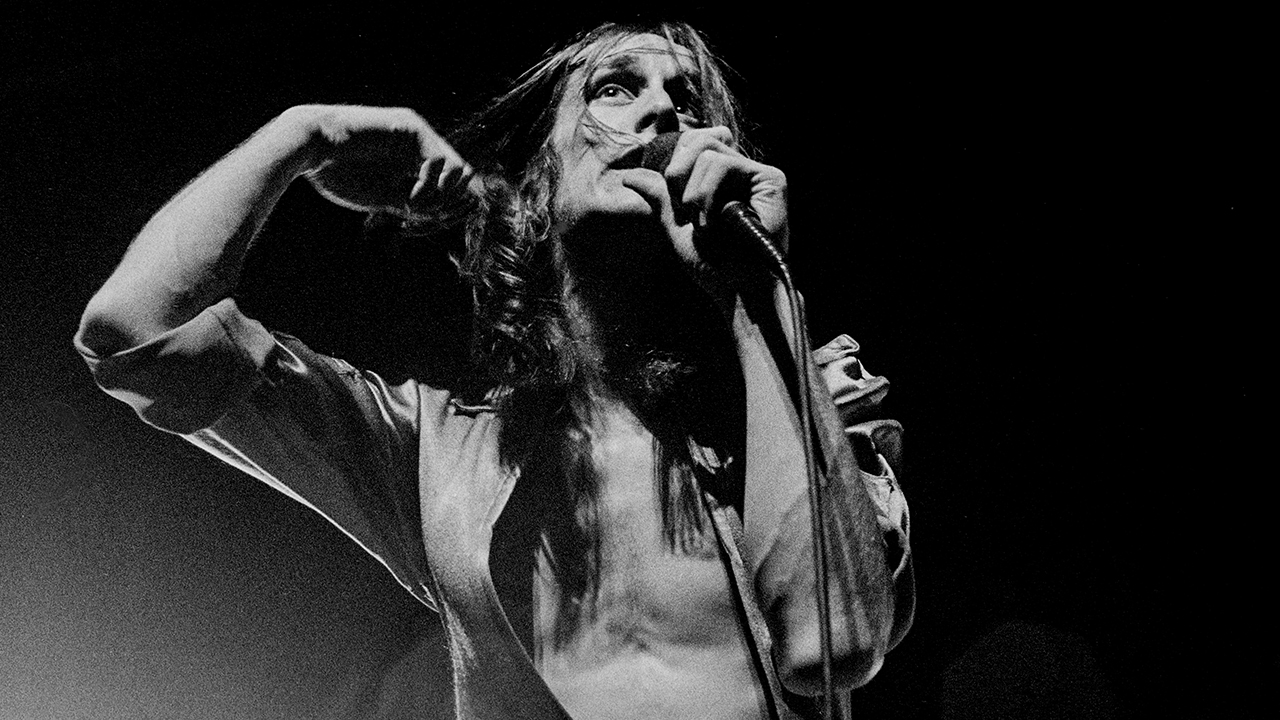

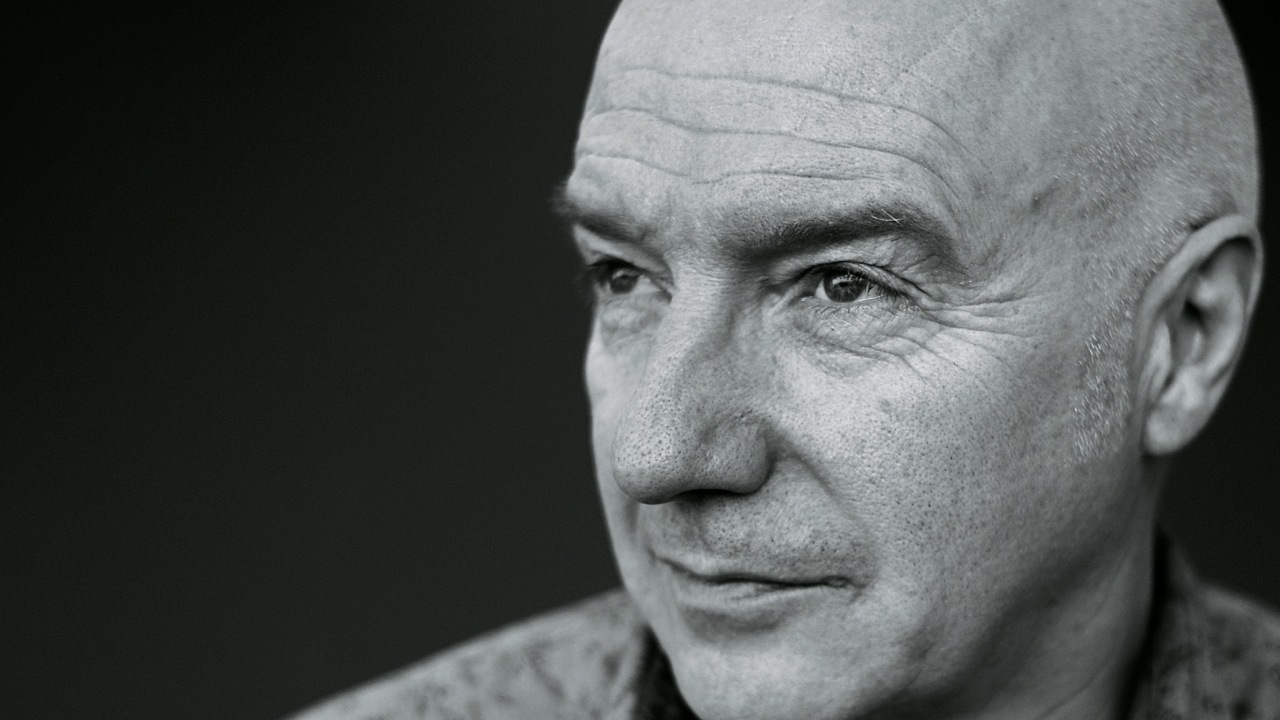

When Midge Ure released solo album Fragile in 2014, the phrase “contemporary prog” appeared in the promotional material. That led to the revelation of Ure’s lifelong appreciation for the genre.

There really is a reference in the press release accompanying Midge Ure’s first album in 12 years to “contemporary prog”.

What, the cuddly former frontman for Scottish proto-boy band Slik, who reached No.1 in 1976 with Bay City Rollers soundalike Forever And Ever? The voice behind Ultravox – Mr Band Aid himself – a purveyor of prog? Surely he’s got as much to do with our beloved music as, well, Les McKeown? Turns out, he’s a closet progger who is more than happy to be outed.

“I’ve just been on tour in Germany,” explains Ure on the phone from his home in Bath, eager to set the record straight and demonstrate his prog credentials. “It was rock meets classical, with a full orchestra. On the bill were Mick Box and Bernie Shaw of Uriah Heep, and they played July Morning [Heep’s own Stairway To Heaven] as this massive, big orchestrated piece, all 15 minutes of it – and I knew it all! Obviously the music my brother used to play when I was growing up – Heep, Yes, ELP – must have filtered through.”

Ure might seem an unlikely prog fan. But then, perhaps not. What he’s proven to be is adaptable. There can’t be many musicians who have covered as much stylistic terrain. Around the time he was in Slik he was invited by Malcolm McLaren to join the Sex Pistols. By 1977, he had formed Rich Kids with ex-Pistol Glen Matlock, and a year later he was working with punk’s experimental wing (Dave Formula, Barry Adamson, John McGeoch) in an early version of Visage, the intention being to make “very white electronic dance music”.

Next, he became John Foxx’s replacement in Ultravox, lured by the latter’s employment of producer Conny Plank, architect of Germany’s kosmische scene. Vienna – and his charity work with Bob Geldof – might have made him a household name, but cut him and he bleeds progressive.

“Americans didn’t know what to make of Ultravox,” he recalls, still amused. “They would reference everyone from Roxy Music to Moody Blues. They likened us to all sorts, including Genesis, because we were really musical. And [keyboardist/violinist] Billy Currie’s background was in classical music – you can hear it in his mid-European chord structures. He even recorded an album with Steve Howe [1988’s Transportation] back in the day, so there’s a connection there.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Ure cites a fascination with new technology as common ground shared by 70s prog musicians and the electronic pop outfits of the early 80s. He was born in 1953 and his first love was the British blues boom of the late 60s, but he “fell in love with” the Mellotron and went to see Yes live in Glasgow, where he was “blown away by their musicianship”.

His love of gadgetry proved his undoing – Rich Kids split up when he tried to introduce them to the synthesizer, anathema at the height of punk – and his making. It was Visage and Ultravox’s cold synth tones and rhythms that proved so influential on the burgeoning electro, hip-hop and house movements of the early- to mid-80s. And Ultravox’s grandiose atmospherics would impact on the next generation of bombastic rockers.

“Muse are the obvious one,” Ure decides. “Their melodic structures, their harmonies and, dare I say it, their pomposity – they out-pomped Ultravox many times! They took it to a completely different level. But anyone who’s heard Ultravox can hear the similarities.”

Like many of his peers, Ure was influenced by David Bowie and Brian Eno’s sojourn in Berlin. “I was in Slik, sitting in a hotel off Kensington High Street, when I heard Low,” he recalls. “It was so removed, production-wise, from anything I’d ever heard before. It was dark and mysterious, Germanic, atmospheric and electronic. I found it absolutely fascinating.”

The fact that the debut album by Ultravox! (when they still bore an exclamation mark, à la krautrock pioneers Neu!) was co-produced by Eno added to their appeal. But it was 1978’s Plank-helmed Systems Of Romance that sealed the deal.

“That was a massive turning point for Ultravox,” he says. “When I joined the band [in 1979], I said I wanted to work with Conny Plank and find out more about this guy who had engineered the early Kraftwerk recordings, and La Düsseldorf. When I went to Conny’s studio [in Cologne], it was inundated with these fantastic musicians. It was a different world.”

By 1980, Ultravox Mk 2 had created the Vienna album, which opened with the seven-minute Astradyne. “Whether it was proggy or not, it was either very stupid or very clever,” he laughs. “The Americans thought it was ridiculous to put a seven-minute instrumental as your opening track. But we didn’t set out to make an album of three-minute singles. We just made an album we were all happy with, one rooted in that Germanic krautrock thing.”

Vienna – the Brit-winning pomp-fest that was kept off the top of the charts by John Lennon’s reissued Imagine and Joe Dolce’s Shaddap You Face – was, according to Ure, only a hit by accident. “It was a hugely atmospheric track that could quite easily have slipped between the floorboards,” he says. “Because it didn’t fit the format. But sometimes when you stick your neck in the noose, it works for you. Look at Kate Bush’s Wuthering Heights or Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody. Sometimes when you don’t do the norm, that’s what changes the world a little bit.”

Few musicians from his – or indeed any – era had travelled so far, so fast: from pop pabulum to Euro-inflected synth hauteur.“It is bizarre,” Ure agrees. “Not that I’m comparing myself, but think of the timescale from Love Me Do to Sgt Pepper: only four years, but a massive growth rate. I had my Slik hit in 1976 and by 1979 I was writing Vienna with Ultravox and Fade To Grey with Visage, hanging out with Eurythmics in Cologne. People usually wait with guns to shoot you because you’re never allowed to grow up and move on. I was one of the lucky ones.”

Talking of the Beatles, Ultravox recorded one more album (1981’s Rage In Eden, described by Ure as “a complete experiment”) with Plank, before collaborating with George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick for 1982’s Quartet. Although he regards the results as “too polished and finely-honed”, it was a thrill to be working with what was, as he puts it, “the Sgt Pepper team”. Ure denies that the following self-produced album, Lament (1984), saw the band repositioned as stadium rock peers of Simple Minds and U2.

“When they started, Simple Minds were a hybrid of Ultravox and Magazine, with a bit of U2 thrown in,” he reflects. “By 1984, U2 had moved into stadium rock and were mega in what was, to me, a slightly dated way, and Simple Minds tried to follow, with lots of thumping bass for people to clap their hands to. Ultravox didn’t do that. We were never into the stadium rock thing.”

Lament was the last album by the classic Ultravox line-up until 2012’s comeback with Brilliant. In the interim, there were albums with different line‑ups, and solo albums, such as 1985’s The Gift – including Ure’s cover of Jethro Tull’s Living In The Past – and 1988’s Answers To Nothing, featuring Kate Bush duet Sister And Brother.

And now here he is with another synth-based feather in his cap: Fragile, a showcase for Ure’s keyboard-based songcraft, and lyrics that explore his difficult recent past, notably his struggles with alcoholism. So why did it take him so long?

“Because I was totally disheartened by the music industry, and I was totally lost, to be honest,” he reveals. “I’d gone through a bit of a personal crisis, I was drinking too much and I had to sort that out. I doubted that I was capable of writing anything that was of any worth any more. Even if I could write anything of any worth, was there any point in putting it out? I firmly believed that the world could survive perfectly well without another Midge Ure record.” Eventually, he gave himself “a clip round the ear” and got on with it. “I wanted to prove I could do it without my songwriting partner, Jack Daniel’s.”

For an artist used to portentous obfuscation, there are moments of lacerating candour on Fragile. Come in, writer of ‘It means nothing to me, oh, Vienna!’ – your time is up. Cue autobiographical own-ups such as, ‘I was dead and I was gone’ (I Survived) and ‘No love, no hope, no self-belief, no pride’ (For All You Know).

“I didn’t need to invent scenarios,” Ure admits. “I wrote about my experiences. It was a way of exorcising ghosts. But it’s not all death, doom and destruction – I talk about the dark side but in a positive way. I wanted to write things that someone, somewhere out there will connect to.”

Entirely self-penned and performed, produced and engineered (give or take a team-up on one track with techno artist Moby and another with Christopher von Deylen of German band Schiller), Fragile is a testament to Ure’s DIY skills. But will it change people’s perceptions of him?

“I think in the public’s eye I swing from being Mick Ronson to being Cliff Richard,” he says, unpredictably. “I don’t want to be either, but that’s how they perceive me: the nice guy next door who sounds nice on telly. But musically I’ve done a lot of things that have been groundbreaking, through Visage and early Ultravox.

“I hope people can say, ‘Yeah, he started off in a band like Slik, but then he did that, then that, then that.’ That’s probably the best thing I could ever give to the music industry.”

Ure joking – Midge’s five proggiest moments...

Conny Plank: It was the presence of Can’s producer that tempted Ure to join Ultravox.

Vienna: He brought quasi-operatic grandeur to the masses with this massive 1981 single.

George Martin/Geoff Emerick: The pair responsible for prog’s ‘year zero’ landmark worked on Ultravox’s 1982 album, Quartet.

Living In The Past: Ure covered Tull’s classic on his 1985 solo debut. “It was one of those tunes I’d sing when I was walking about in my army jacket and hair far too long for school,” he says.

Collaborating with Kate Bush: “I was working with her on a Prince’s Trust concert,” he explains. “I’d always been a big fan, and I was pissed enough to ask her. It was one of the highlights of my career.”

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.