“No one expected it to sell, but it did sell, didn’t it?”: the crazy story of an era-defining 80s classic that shifted millions but had such an expensive sleeve it sold at a loss

Someone forgot to run the numbers…

New Order were still finding their feet as their thoughts turned towards making a second album. Their 1981 debut Movement felt very much like a record mired in their past. Released just a year and a half after the suicide of their former singer and Joy Division bandmate Ian Curtis and the decision to begin again under a new name, it was not the fresh start they really needed.

Some of its songs had even been played live by their former incarnation and the decision to make it with Joy Division producer Martin Hannett only strengthened that his was Joy Division minus their mercurial frontman.

But next came one of the boldest and most brilliant reinventions in music. In the aftermath of Movement, the quartet – Joy Division trio Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris had been joined by Morris’ girlfriend Gillian Gilbert on keyboards and guitar – had spent time clubbing in New York, the heady sounds of Italian disco and synth-laden Europop giving them the idea to make their sound more electronic and upbeat, the polar opposite of the doomy post-punk they had made of Joy Division.

You can understand why they would so willingly embrace the euphoria of the dancefloor – after the tragic loss of Curtis, it was time to let a little light in.

Back in their rehearsal space in Manchester and then at Britannia Row studios in London, they got to work on a trailblazing new sound, working with synthesisers, samplers and drum machines, programming and sequencing beats. It was an arduous process but out of it, a classic was born. Blue Monday, which took a whole year to make from start to finish, would change New Order’s world.

A thrilling meld of forward-thinking electronic-pop with the post-punk groove and detached vocal cool of their former work, it is one of the most influential songs of all time. It holds the record as the biggest-selling 12” ever, and yet it was never envisaged as a single or even a proper song when the band began work on it.

“It started as an instrumental, because we didn't believe in encores,” Hook explained in an episode of the Song Exploder podcast dedicated to the track. “We were so young and idealistic that we thought, ‘We've played our set, we've played the songs that we've worked on. Why should anybody want anything else?’ And then someone came up with an idea of, what about if we ‘played’ the synthesizers after we'd gone off?”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

But as it began to take shape, everyone who heard it knew something special was brewing. Each sonic left-turn added something knew as an accidental classic slowly came together. As well as originating it as an instrumental, it was also originally meant to be entirely electronic until engineer Michael Johnson suggested that Hook put live bass on it. His iconic riff was inspired by the languid playing on Ennio Morricone’s score for Western classic For A Few Dollars More.

When the band’s late manager Rob Gretton heard where they were going with it, he was insistent that the track needed singing on it. “He was adamant that we needed to put vocals on it,” recalled Hook. “And we fought valiantly not to do it. When we lost Ian Curtis, we lost a lot because he was so good at this, and words came to him so easily and so naturally. He really was the, the champion of it.”

It was left to Sumner, who had now become de facto frontman, to lay down a nonchalant, weary vocal that would elevate everything else, somehow adding to the euphoria in the way that he sounded so non-plussed.

“We all had goes at singing,” remembered Morris. “And Bernard was quite good, because you could tell he didn't want to do it, but he did it in a kind of half-hearted, disinterested way that was somehow quite charming. So Bernard ended up getting the short, or longest, straw, and inherited the curse of the lead singer.”

Despite the fact its human elements are so essential, Sumner still sees it as something more machine-based, pointing out all the myriad rhythm tracks – the beat, the bassline, the hi-hats – all work in unison together to create something bigger. “The way I see it, it’s all the gears churning in sync with each other,” he said. “It’s less of a song and more of a beat generator. It’s a guaranteed dancefloor filler.”

Released in March, 1983, as the first single from New Order’s game-changing second record Powers, Lies & Corruption, Blue Monday became an unexpected hit and set New Order up for what would become a hugely successful decade.

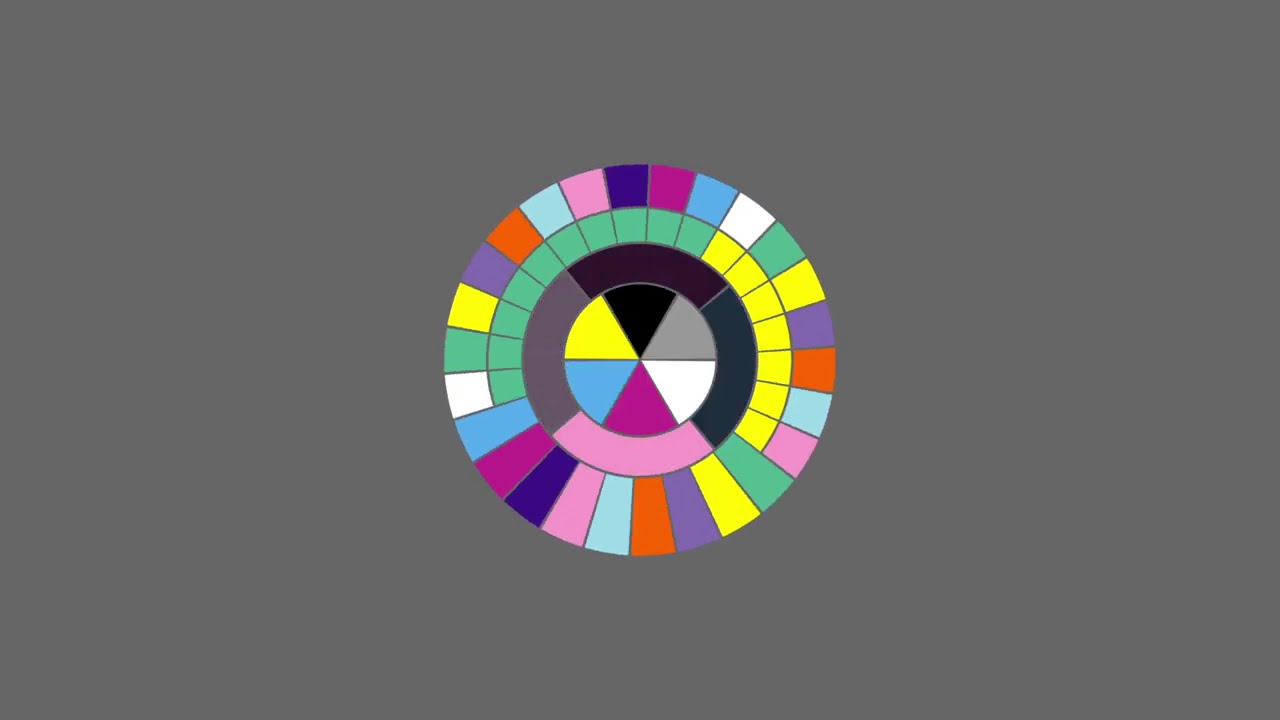

Of course, if anyone involved in the endeavour had any inkling it would become such a success, the band and their label Factory might not have been so loosey-goosey with the economics of its iconic album sleeve. Designed by long-term Factory collaborator Peter Saville, it was meant to resemble a floppy disk – nodding to the use of computers and technology in its creation – and was incorporated holes that required three special die-cuts and also came with a silver inner sleeve.

Not only was this not cheap, it ended up so expensive that the label lost money for each copy sold. Factory boss Tony Wilson claimed they lost 5p every time someone bought a copy of Blue Monday, whilst Peter Hook has said it was more like 10p, asserting that it was on sale for £1 and cost £1.10 to manufacture. “No one expected it to sell, but it did sell, didn’t it,” Saville shrugged to the Telegraph a few years ago.

It was partly due, the designer said, to both Factory’s ethos of putting art first (“if it existed today, you could quite credibly give it the Turner Prize,” he said) and the fact that they were not exactly armed with the most on-it finance department. Everyone was more focussed on getting the music out, and Saville delivered his artwork so close to deadline, there was no time to check. “I do not think that anybody gave Factory a quote because it was so late,” he stated, “and within hours of me having delivered the artwork it would go into production.”

Whilst all this meant that New Order made no money from their breakthrough hit at the time of release, its legacy is a little more fruitful.

“It’s an insane tune,” Peter Hook said. “I sort of hang round like a vampire with all these young DJs and every bloody DJ, no matter how young he is or how old he is, from Carl Cox to Skrillex or whatever, the first thing they say is Blue Monday, that’s inspired me. It’s a weird thing to live with but what a compliment it is.”

Sumner, meanwhile, recalls being in a Berlin club once when the song came on. The whole place erupted. “Everyone got up, literally everyone,” he marvelled.

Rob Gretton had told the band it was going to be a hit, and he was right. “We were like, ‘I don’t think so’,” Gilbert remembered. “We couldn’t imagine it. It’s very upbeat, it completely changed out outlook.”

Over four decades later, it sounds as innovative and electrifying and immediate as ever. Have a listen below:

Niall Doherty is a writer and editor whose work can be found in Classic Rock, The Guardian, Music Week, FourFourTwo, Champions Journal, on Apple Music and more. Formerly the Deputy Editor of Q magazine, he co-runs the music Substack letter The New Cue with fellow former Q colleague Ted Kessler. He is also Reviews Editor at Record Collector. Over the years, he's interviewed some of the world's biggest stars, including Elton John, Coldplay, Radiohead, Liam and Noel Gallagher, Florence + The Machine, Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Pearl Jam, Depeche Mode, Robert Plant and more.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.