Your essential guide to every studio album by The Velvet Underground

The Velvet Underground reshaped the sound of rock'n'roll with four albums that continue to have an incalculable influence on the musical zeitgeist. The less said about their fifth, the better

Arguably the most influential alternative rock band in history, The Velvet Underground’s back catalogue may be relatively scant, but the four albums they released with Lou Reed as their driving force, initially alongside John Cale, not only reshaped the sound of rock’n’roll, but expanded expectations of what it could be.

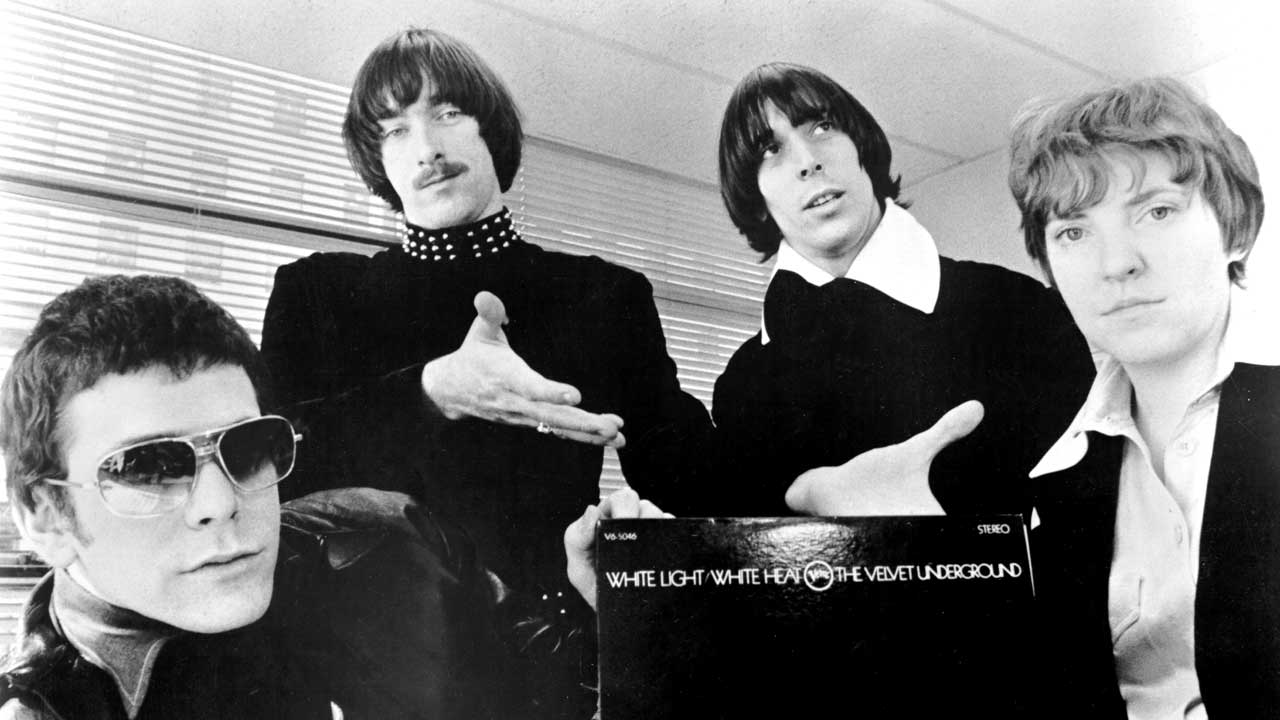

The Velvet Underground comprised NYC-born vocalist/guitarist Reed (an ex-Syracuse University Journalism major who’d more recently been supplying sound-alike pop hits to order for budget label Pickwick), viola and bass-toting Cale (an instinctively experimental Welsh classicist with a taste for the avant-garde), guitarist Sterling Morrison (quietly preppy, his solid melodic style the essential yin to feedback-favouring, off-the-leash Reed’s ill-disciplined, ear-thrashing yang) and drummer Maureen Tucker, whose metronomic beat provided essential grounding upon which her fellow Velvets could let their impassioned imaginations run riot.

Reed’s transgressive, uncompromising lyrics (inspired by writers Hubert Selby Jr and Nelson Algren) introduced a teenaged constituency more familiar with the sanitised romantic fiction of moptop pop to society’s flipside, to copping smack and shooting speed in a twilight world of sado-masochism and blurred sexuality.

As word of this extraordinary combo spread, their existence came to the attention of renowned pop artist and publicity magnet Andy Warhol, who became their manager and mentor. Warhol introduced them to German-born model, muse and ‘chanteuse’, Nico, secured them a recording deal with MGM, and ‘produced’ their debut album (in so much as he allowed them to do precisely as they pleased).

And the rest is history.

Aside from the quintet of albums released under their name while they were still, technically, a going concern (including a swansong that featured no original members whatsoever), the Velvets appeared on a handful of posthumous releases, not least a brace of post-Cale live albums: the double 1969 and, more interestingly, the lo-fi verité snapshot of the Reed-fronted Velvets’ last stand, Live At Max’s Kansas City.

When Lou Reed walked out on The Velvet Underground (three months prior to the release of 1970’s Loaded) initially taking a job as a typist with his father’s accountancy firm, the band’s influence, not least on the young David Bowie and a nascent punk generation, was yet to become apparent, but by the time Lou Reed, John Cale, Maureen Tucker and Sterling Morrison reformed to tour Europe in 1993, they were widely recognised as one of the most important rock bands in history, of incalculable influence on the existing musical zeitgeist.

They still are.

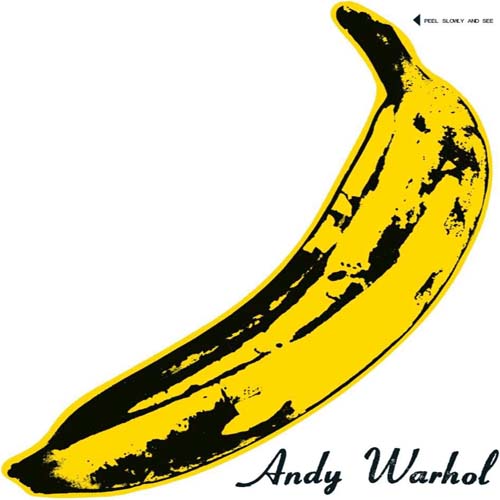

The Velvet Underground And Nico (1967)

You can trust Louder

There was so much more to The Velvet Underground than pushing the boundaries of exactly how far too far could go, which is why their legend looms so large. There are whole heaped spoonfuls of irresistibly melodic sugar secreted on this stratospherically acclaimed debut disc to help the over-cranked prototype noise rock medicine go down.

Its subtly paranoic opener Sunday Morning immediately lulls the listener into an entirely false sense of security, with its Cale-rendered celeste intro and gently lulling vocal tones from Reed, before I’m Waiting For The Man’s two-chord riff-driven clangour drags the unsuspecting observer straight uptown to Harlem with leering narrator Reed, impatiently clucking for a fix, drawling and insistent. Pop’s rosy-cheeked childhood suddenly jars into a delinquent rock adolescence over the course of four-and-a-half minutes. And nothing can ever be the same again.

Nico takes centre stage for Femme Fatale, an entrancing beautiful song haunted by an underpinning discord that yields once more to relative tumult. The still astounding viola-yowling, brain-jangling riff of Venus In Furs grinds by at funereal pace as Moe T. marks time with two beats of a bass drum, one shake of a tambourine. And then there’s the S&M-charged lyric: ‘Shiny, shiny/Shiny boots of leather’. We’re not in Penny Lane now, Toto. Four songs in and history’s already been made at least twice. Anyway, no-one’s here to walk anyone through an album that can feel akin to the Valley of the Shadow of Death hand-in-hand, track-by-track.

Save to say things get even darker - a nihilistic junkie Reed mainlining fatalistically on the unprecedented and unvarnished Heroin, the caterwauling sonic maelstrom of The Black Angel’s Death Song and the ear-splitting, off-the-hook finale, European Son - and even more breathtakingly beautiful: the diaphanous Nico-breathed I’ll Be Your Mirror.

Best album ever? Well, I wouldn’t bet against it in a knife fight with The Dark Side Of The Moon.

Great pink banana-stickered Warhol-conceived cover, by the way… But that’s another story.

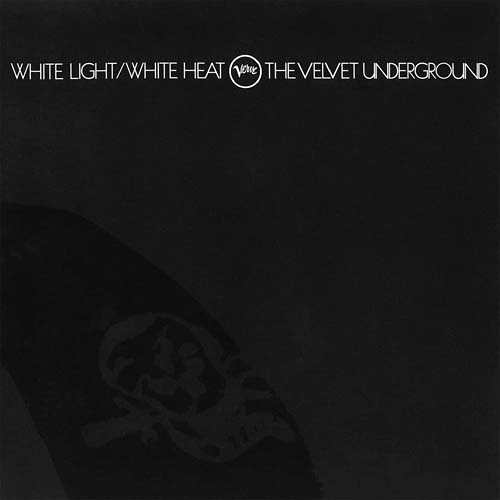

White Light/White Heat (1968)

While The Velvet Underground And Nico’s gradual seduction of posterity was facilitated by former Pickwick hit-chaser Reed’s finely-tuned, if often reluctantly deployed ear for the commercial (that saw him instinctively counter every avant-garde challenge with a comforting, milkman-friendly whistle-able tune), White Light/White Heat marked the moment he removed his kid gloves and made an uncompromising album for the ages.

Despite significant press and persistent gigging their debut sold poorly, so Reed sacked Warhol and dispensed with the services of Nico. Tom Wilson, who had been the first album’s producer in all but name was retained for White Light/White Heat and entering Mayfair Sound in Manhattan the band recorded loud, fast and furious. Employing the same cranked-to-distortion, improvisational modus operandi as they had for recent gigs, they casually set about subverting the future.

WL/WH’s title track is punk incarnate, a template for slack-jawed aggression, repetitive, insistent, undeniable, yet despite its jarring amphetamine chomp, Reed’s lead vocal retains its louche, shades-indoors languor. As this particular performance arrived into 1968, it might not have been the coolest thing that anyone had ever heard, but it might as well have been. Everything that the seventies would be had already arrived.

Follow that…

The Gift combines John Cale’s spoken word performance of a deliciously morbid Lou Reed short story with a feedback-peppered blues-rock grind (warning: threat, injury detail), Lady Godiva’s Operation applies another Reed narrative, this time concerning a grisly, morphine-woozy, gender-reassignment procedure, that appears to go horribly wrong, as the band supply appropriately disorientating Eastern-tinged accompaniment and Cale manfully impersonates an iron lung. Here She Comes Now, originally written for Nico, is the closest the band come to contemporary pop-rock and offers brief respite before side two delivers the Velvets in excelsis.

If you are in the market for a Dexedrine-babbled psychedelic Wuthering Heights-in-reverse then you’ve come to the right place. Frantically Tuckered, hectically ejaculated garage rock seizure I Heard Her Call My Name is all of this and more. Reed’s mind splits open, in a searing catterwaul of Hendrix-with-a-head-injury guitar squalls, at least twice over the course of this extraordinary, borderline necrophiliac assault on the senses.

No sooner has Reed’s tortured guitar clicked into blessed silence than Sister Ray enters the fray. For many the Velvets’ defining statement, Sister Ray recounts a lurid, blurry tale that involves drag queens, sailors and smack. An orgy inevitably transpires, though not a particularly energetic one, the police put in an appearance and there’s an awful lot of ding-dong sucking going on. As this extraordinary John Rechy/Hubert Selby-styled narrative plays out the band hammer their way through an ever-more-disturbed combination of Booker T. and Ornette Coleman. And, oh yes, it goes on for 17-and-a-half minutes.

White Light/White Heat is an album that you really ought to own. It may not be as immediately palatable as its predecessor, but to those with a taste for uncompromising rock… Well, it’s kind of the reason we’re all here.

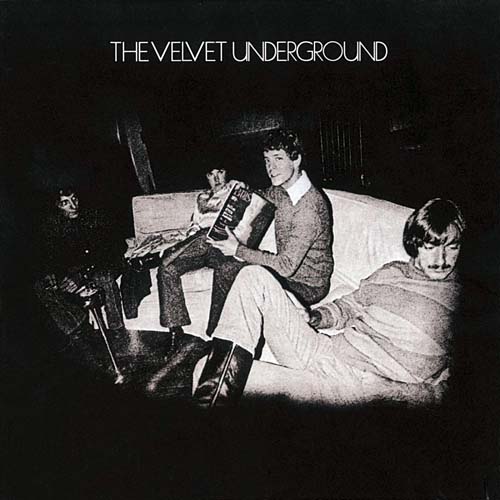

The Velvet Underground (1969)

Placing your stylus on The Velvet Underground’s eponymous third for the first time you could be forgiven for thinking that you’d been supplied with the wrong disc. Delicately rendered opener Candy Says could not be further from the sordid delinquent brutality of Sister Ray. The Velvet Underground sound like a different band, and in many ways, they are. John Cale, the band’s strongest link with the avant-garde and the experimental, was sacked within days of White Light/White Heat’s completion. Lou Reed, tired of arthouse anonymity, had a record company demanding hits, and Lou? Lou had had his heart set on becoming a rock'n'roll star since forever and, at 27-years of age, wasn’t getting any younger.

Multi-instrumentalist Doug Yule (effectively a younger, prettier version of Reed) was recruited to replace John Cale, and took lead vocal on Candy Says (outwardly beatific, an enduring song laced with paranoia and self-loathing, and one of Reed’s best). The Velvet Underground was self-produced in Hollywood, and aside from The Murder Mystery (a disorientating, schizophrenic, self-consciously challenging melange of simultaneous vocals: Reed and Yule in the right stereo channel, Morrison and Tucker in the left, allied to raga spirals and manic piano), followed a relatively conventional, almost spiritual, path.

What Goes On blazes along in a style that can only really be described as catchy, Doug Yule’s central organ solo introducing a hitherto unexplored keys element, Some Kinda Love’s mantra-esque intimacy tickles along lasciviously as Lou waxes salacious before Pale Blues Eyes, possibly one of Reed’s finest love songs (that he’d been working on as early as ’65 with Cale), gentle, understated, propelled by the most unassuming tambourine in rock: the album’s first real masterpiece.

Beginning To See The Light brims with apparent spiritual and emotional confidence, before concluding with the significantly more revelatory coda ‘How does it feel to be loved?’. While the album’s final track, where Moe Tucker takes centre-stage to sing After Hours, supplies a charming, post-Murder Mystery denouement. Despite the Velvets’ change of tack, The Velvet Underground failed to chart. Astonishingly, it sold even less than both its predecessors. That said, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it. Other than the fact that it exists in such exalted company. After all, even the Velvets can’t make their best album every time.

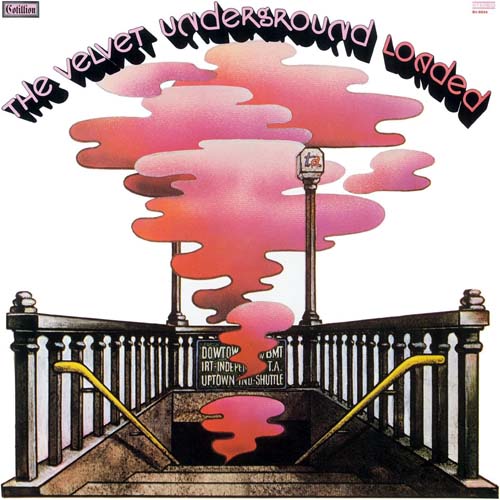

Loaded (1970)

The Velvet Underground’s fourth album was aimed squarely at radio. An impatient Atlantic demanded an album ‘loaded with hits’, and Lou Reed set to work delivering a brace of stone cold classics in the shape of Sweet Jane and Rock And Roll. Both tracks were significantly beefed-up, and their proto-metal/proto-punk credentials boosted, on solo Reed’s ’73 live album Rock ’N’ Roll Animal, but here, in their original studio incarnation boast a warm, subtle power that’s hard to beat. Reed’s vocal performances on both acoustic guitar riff-driven songs are without doubt the very best of his career. How could they not have been hits?

How indeed… They weren’t even released as singles.

There are fillers on Loaded, and while the likes of Cool It Down, Train Around The Bend, Lonesome Cowboy Bill and, inexplicably lengthy closer, Oh! Sweet Nuthin’ are not without their modest charms, they’re all a bit ‘let’s run it up the flagpole and see if anyone salutes’. Desperate attempts to contrive commercial material that don’t really work. And Reed (specifically aggrieved by an unauthorised re-edit that saw Sweet Jane’s bridging section excised from the album’s final mix), left the band three months before Loaded’s release.

Arguments continue to rage as to whether Loaded would have been a better album if the band had waited until Tucker (pregnant with her first child) was in a position to record her drum parts, Doug Yule, his brother Billy, Adrian Barber and Tommy Castagnaro all deputised, but Moe’s idiosyncratic style was missed. Most especially by Reed. That said, the enduring commercial appeal of Sweet Jane and Rock And Roll may not have been quite so mainstream-friendly if not for Doug Yule’s relatively pedestrian four-to-the-floor.

Other than the obvious time-honoured, Metallica-covered all-time greats, there are a pair of often-overlooked always-the-bridesmaid classics secreted on Loaded, both of which Lou Reed selflessly handed to Doug Yule to sing. Upbeat opener Who Loves The Sun? is two-minutes-forty of mega-pop pizzazz weirdly hobbled by a very poor, very obviously edited-in, self-sabotaging ill-judged and off-kilter guitar tangle, while New Age, a bewitching vignette concerning a chance meeting between a film fan and an over-the-hill actress, boasts a melody line just unorthodox enough to inveigle its way into your subconscious forever. Not to mention, a coda to die for.

So that was that then. Following the departure of principal songwriter, Lou Reed, having delivered four of the greatest and most influential albums of all time, The Velvet Underground bowed to the inevitable and called it a day. Except they didn’t.

Squeeze (1973)

Lou Reed left The Velvet Underground in August ’70, Sterling Morrison followed a year later. Moe Tucker was all set to appear on the band’s widely unanticipated fifth album. Until she was unceremoniously sacked. Sole remaining member Doug Yule - originally recruited as aging juvenile Reed’s slightly less craggy, mangenue-voiced stunt double - elected to record the entire thing himself (with unlikely assistance from Deep Purple’s Ian Paice on drums). Result: no original members; no direct link to the pioneering Velvet Underground line-up that recorded White Light/White Heat. Just Doug. And a moonlighting Purp.

The resulting record, Squeeze, is not a bad album, it’s a surprisingly unremarkable album in many ways, but it’s not actually bad. What it is not, is a Velvet Underground album. It’s a Doug Yule solo record.

Lou Reed’s first few solo records - his eponymous debut, Transformer and even Berlin are far closer to being Velvet Underground records than Squeeze in that they are populated with a significant number of tracks that found their genesis as Velvet Underground songs (Ocean, Andy’s Chest, Satellite Of Love, Caroline Says II).

Squeeze’s material isn’t edgy (Doug Yule’s lyrics as far from transgressive as the average vacuum cleaner instruction manual). They’re a bit like McCartney songs that never quite made it to the final cut of the White Album (the piano driven Crash especially, with its ill-advised deployment of unsophisticated stereo-panning). Which, again, is not to say that they’re bad.

Mean Old Man cracks along nicely, Friends exhibits lessons learned at Lou’s right hand, but even Doug Yule realised that he was out of his depth, calling the album “A nice memory, but an embarrassment” and defining Squeeze’s autonomous recording process as "Me leading myself (was)… like the blind leading the blind”.

In February 1973, as Squeeze arrived into record stores with minimal fanfare, John Cale released his third solo album Paris 1919 to positive reviews (Rolling Stone calling it ‘a masterpiece’), Nico was filming Les Hautes Solitudes with French director Phillipe Garrel and preparing material for her fourth Cale-produced solo effort The End, Sterling Morrison was studying at The University of Texas (he’d eventually attain a PhD in Medieval Literature) and supplementing his income as a tugboat deckhand in Houston, Maureen Tucker was raising a family in Phoenix, Arizona and Lou Reed - his typing career behind him - released Satellite Of Love as the second single from his second solo LP, ’72's David Bowie/Mick Ronson-produced, Transformer.

The first single from the album, Walk On The Wild Side had finally afforded Lou Reed the hit single (top 20 in the US, top ten in the UK) that had always eluded the Velvets.

Squeeze, meanwhile, true to proud Velvet Underground tradition in one respect at least, quietly stiffed on its lily-white arse.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.