“Nothing in this band does what it's supposed to do”: how R.E.M. showed the world they were the real deal on 1985’s Fables Of The Reconstruction

The story of Michael Stipe & co.’s strange and brilliant third album.

Reflecting in 1985 on what it was that really made R.E.M. tick, frontman Michael Stipe said it was a matter of the unconventional. “Nothing in this band really does what it’s supposed to do,” the singer told Musician magazine. “The guitar doesn’t necessarily play the parts a guitarist is supposed to play. The bass is much more melodic than bass is supposed to be in rock’n’roll.”

At that point, the Athens, Georgia quartet were only three albums in but a pillar that remained right the way through to their split in 2011 had been set: R.E.M. were always the band who never did what they were supposed to do. A leftfield college-rock group weaving arty sensibilities and FM melodicism are not meant to go on to become one of the world’s biggest and most important rock bands.

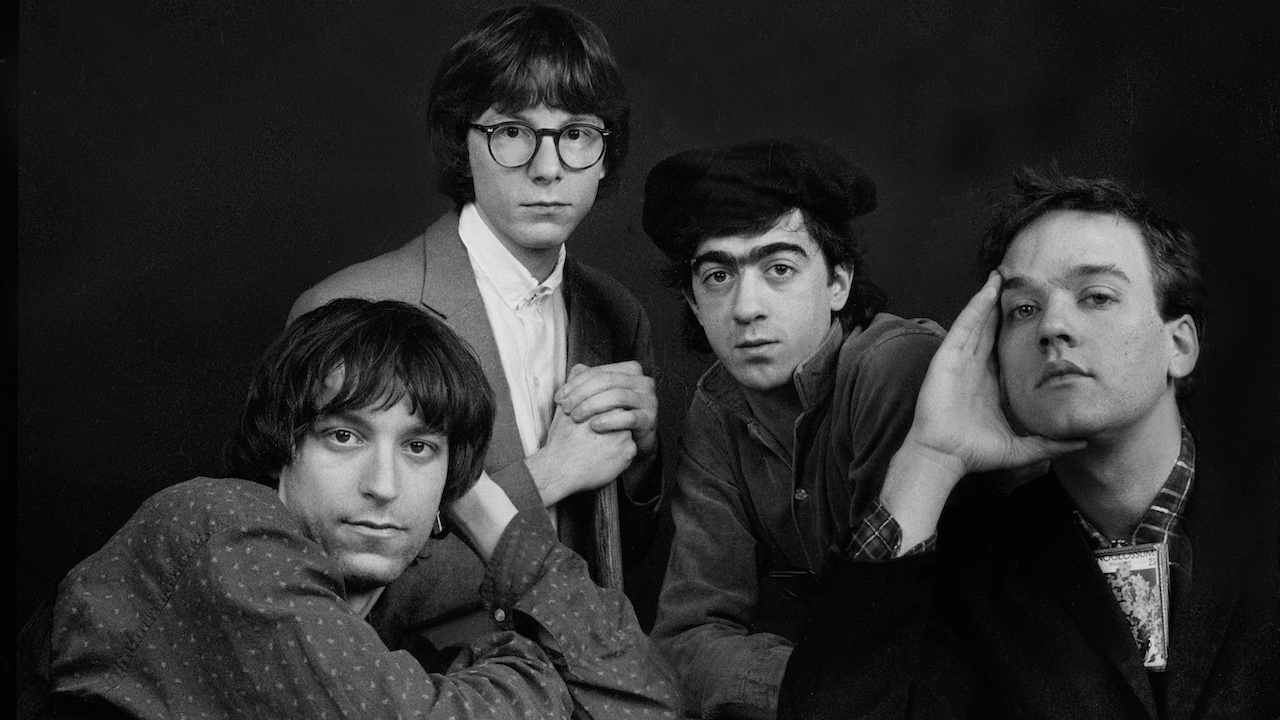

But that’s exactly what happened for Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, Mike Mills and Bill Berry. At the point that Stipe mused on the band’s DNA, they had just released their third album Fables Of The Reconstruction. For a while, it was a bit of an outlier in the R.E.M. catalogue, a tad unloved and under-appreciated next to some of the mightier 80s efforts that led to their pair of early 90s masterpieces Out Of Time and Automatic For The People.

But time has been good to Fables…, an album lacking in some of the big anthems that elevated its counterparts but one that remains crucial to the R.E.M. story. Because more than them being a rock band, more than them writing big hooky choruses or emotive, poignant singalongs, R.E.M. were a strange band. And Fables… is one of their strangest.

Lyrically, it’s also where Stipe came into his own, casting a Southern Gothic shadow over these tales of remote towns and their eccentric inhabitants, of time and distance and detachment. “Living in the South all my life, having all my roots here, transfers in a big way over to my contribution to the music,” Stipe said at the time. “We probably could be from Chicago but we’d sound a whole lot different if we were. Fables Of The Reconstruction has a lot to do with where we live.”

“It wasn’t until Fables.. where I really felt like I had created a little area where I could work and feel comfortable with my output,” Stipe told me a few years ago. “Until then, I was really recording stuff that we had performed live and some of it is complete nonsense. Murmur is largely [like] Sigur Rós and the Cocteau Twins, the human voice as an instrument and the experience of listening to something for its emotive and emotional attributes much more than any kind of narrative or sensible storytelling. It wasn’t until Fables… that I felt like I had created a little niche where I could work, where I felt like I really reached a level of discernible accomplishment.”

In contrarian R.E.M. style, key to the band starting to feel at ease with their own talents on Fables… was them taking themselves out of their comfort zone in dramatic fashion. Their first two records, 1983’s Murmur and 1984 follow-up Reckoning, were made with North Carolina producer Mitch Easter but here they chose to mix things up. “We wanted a different sound,” explained drummer Berry. “We didn’t want to seem lazy.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Living in Athens, Georgia, they enjoyed what Peter Buck described as a “laid back” life and they could hardly have chosen a more dramatic overhaul for making their third album. After considering Van Dyke Parks, Harvest producer Elliot Mazer, The Police collaborate Hugh Padhgam and Elvis Costello as options, the band settled on Joe Boyd as producer, with Peter Buck keen due to his work with Fairport Convention and Richard Thompson.

Deciding that Boyd would work best in his own London-based studio, they upped sticks to the English capital, Stipe a little too relaxed about the culture shock about to greet them. “I literally jumped on the plane wearing what I had on and a toothbrush,” he recalled. “I got over there and after about four days I started to stink a little and had to go out and buy a pair of tennis shoes, two pairs of socks, two pair of pants and a shirt.”

He may well have chucked a warm padded coat into the trolley too. The UK was in the middle of a miserably cold and wet winter. “It rained every day it wasn’t snowing,” Buck grumbled to Melody Maker’s Allan Jones, the band discovering that Boyd’s Livingston Studios, based in London’s Wood Green, was a very long way from home. “I hate to say it was hard,” Buck recently told Uncut. But… “It was a tension-filled time.”

Boyd himself attested to that in a chat with the Conversations With Tyler podcast. One issue, he stated, was that they had chosen to stay in a hotel in central London an hour’s drive from the studio rather than the local option he’d suggested and arrived at the studio “a bit battered” every day. The other, he explained, was that there was some internal friction going on.

“There were tensions in the group that I was unaware of when I was dealing with them,” he remembered. “The rainy weather and the hour-long drive to the studio did not help. But somehow, my way of working with them captured that mood. I did the tracks that I felt I could contribute something on.”

Recording in a hurry, as they had done with their previous two records (the bulk of second album Reckoning was done in just two days), the band decided that to rein it in a little, keen to see what effect working a little slower it would have on the music. “We were trying to relax in the studio,” said Stipe. That slowing down was entirely relative, of course – Fables… was still mostly completed in just over a week.

The unease in which it was created may well have sullied the experience for the band at the time, and for years fans assumed the band themselves were not that keen on the record. It’s a take that Buck tackled head-on in his liner notes to accompany a 2010 reissue. “

“Over the years a certain misapprehension about Fables Of The Reconstruction has built up,” he wrote. “For some reason, people have the impression that the members of R.E.M. don’t like the record. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In the 15 years since, that assertion has all but evaporated, Fables Of The Reconstruction now celebrated alongside the finest of R.E.M. classics. And so it should be, for what it offered there and then - the giddy, jangly new wave of Can’t Get There From Here, the moody, majestic guitar-pop of Driver 8 and the jagged, minor chord post-punk of Auctioneer (Another Engine) – but also for the signposts it erected for where they might go next. The subtle menace of Feeling Gravity’s Pull, for example, would eventually shapeshift into a more beautiful form on Automatic For The People, and rustic closer Wendell Gee might well be considered a blueprint for the swaying alt-country sound explored more fully on Green and Out Of Time.

Four decades later, what Fables Of The Reconstruction really sounds like is R.E.M. tapping in to all the things they could be for the first time. They had blown the future wide open.

Niall Doherty is a writer and editor whose work can be found in Classic Rock, The Guardian, Music Week, FourFourTwo, Champions Journal, on Apple Music and more. Formerly the Deputy Editor of Q magazine, he co-runs the music Substack letter The New Cue with fellow former Q colleague Ted Kessler. He is also Reviews Editor at Record Collector. Over the years, he's interviewed some of the world's biggest stars, including Elton John, Coldplay, Radiohead, Liam and Noel Gallagher, Florence + The Machine, Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Pearl Jam, Depeche Mode, Robert Plant and more.