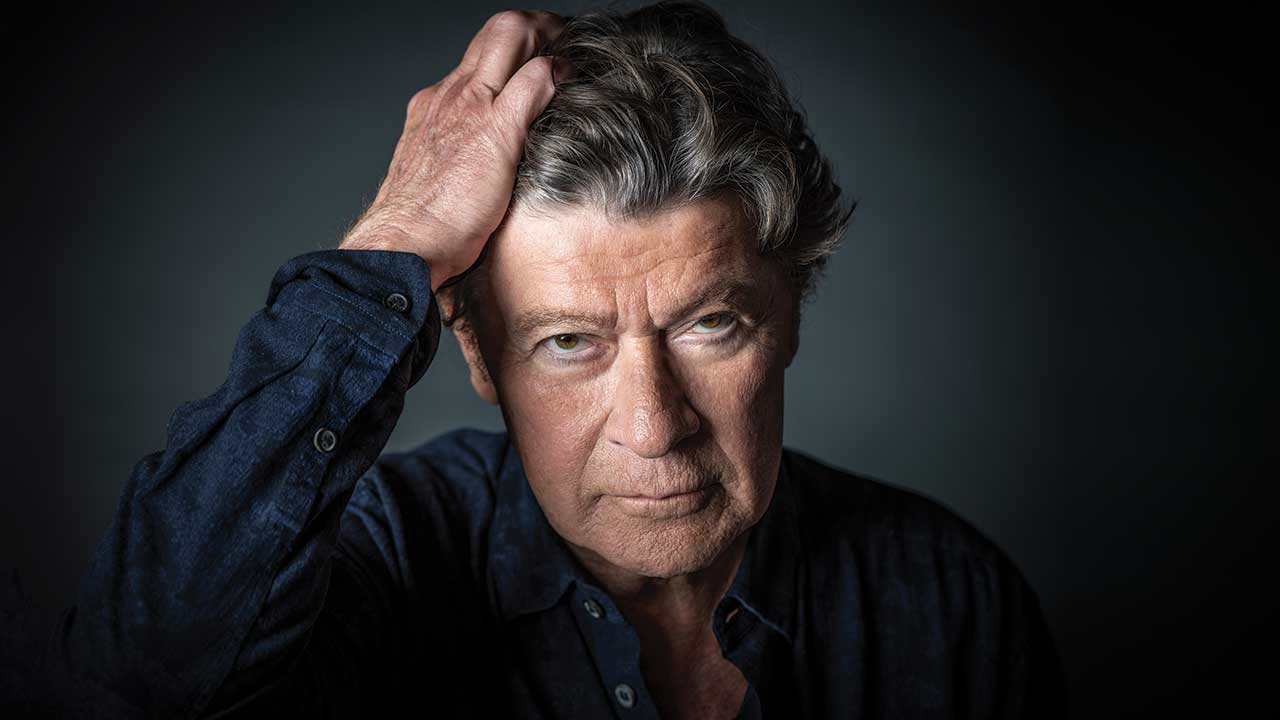

Robbie Robertson interview: life with Bob Dylan, Martin Scorsese and The Band

Few musicians called a ‘legend’ really deserve the accolade. Even if being chief architect of The Band was all he’d ever done, singer-songwriter Robbie Robertson is one who does

Robbie Robertson is trying to write his second volume of autobiography, but he’s not finding it easy.

“I’m about halfway in, give or take,” he says. “I’ve got my head down, but I’ve got a lot of other stuff going on. I just haven’t been able to do that isolation thing with it yet, finding that quiet room where I can go and shut off the outside world.”

Given his current workload, his predicament is understandable. First off, there’s the business of promoting Sinematic, his latest solo album. It’s a record that feels deeply personal and bracingly political in places, shot through with rich imagery and delivered in Robertson’s trademark leathery growl.

He’s also been busy with the soundtrack to The Irishman (the new gangster epic directed by his friend Martin Scorsese), as well as helping prepare a 50th-anniversary edition of The Band’s self-titled classic second album. Then there’s Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson And The Band, a documentary based on his 2016 memoir, Testimony. All of these activities tend to inform one another, so what emerges is a portrait of Robertson’s creative life using different angles and multiple timelines.

And what a life it’s been. He was born on July 5, 1943. Raised in Toronto, Canada, Robertson began playing in bands in his early teens. The big break came in 1960, when rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins hired him for his backing band The Hawks, who included drummer Levon Helm. Alongside Richard Manuel, Rick Danko and Garth Hudson, The Hawks joined Bob Dylan on his infamous electric tour of 1966, before settling in at Woodstock in upstate New York to record Dylan’s The Basement Tapes.

Post-Dylan, The Hawks morphed into The Band and Robertson became their chief songwriter. Their inspired synthesis of R&B, gospel, country and blues redefined the parameters of roots-rock on timeless albums such as Music From Big Pink, The Band and Stage Fright, before the original incarnation – beset by the drug addictions that would lead to a schism in their relationships – bade farewell with The Last Waltz in 1976.

By the time his former bandmates reconvened in the early 80s, Robertson had already moved into production and Hollywood film soundtracks, and would continue as a solo artist. And the 76-year-old clearly is still going strong.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

How did Sinematic take shape amid your various other projects?

I was just in this mode, very much spurred on by everything that I was working on. And it was highly unusual for me to feel comfortable with just throwing everything in the soup. It’s partly to do with the story of The Irishman and the music I’m doing for the movie. The last track on Sinematic is Remembrance, which is used for the end titles. The movie has violent subject matter, so there were places in the songwriting where I went to that same place: Shanghai Blues, the beginning of Street Serenade and I Hear You Paint Houses, which I do with Van Morrison.

At the same time, we were working on the documentary about The Band and also putting together the fiftieth anniversary of The Band album. And I’m writing volume two of my memoirs, so all those things spilled into it. I thought: “Let’s just celebrate life and let everything be a part of it.” I really enjoyed embracing everything - all is one and one is all.

As a kid I had all of these big dreams, and I think some people felt challenged by that

Robbie Robertson

Were certain songs difficult to write? Once Were Brothers, for example, addresses the sometimes fraught relationships within The Band.

The fact that I’ve lost three of my brothers [from The Band] is devastating. And of course it’s sad. I needed to write this to help myself deal with that mourning. The fact that the song turned out the way that it did made us want to call the documentary Once Were Brothers. So it’s digging deep. But that’s part of really getting inside that place you want to go to when writing songs.

Dead End Kid seems very autobiographical. The song describes an attitude you were often faced with while growing up in Toronto: ‘They said you’ll never be nothin.’ When it came to making a career from music, how much of an incentive has that been over the years?

That kind of stuff can work two ways. I was a kid going: “My God, one of these days I want to write music and go out into the world. I want to do this and change that.” I had all of these big dreams, and I think some people felt challenged by that. People would say to me: “You’re just a dreamer. Everyone talks about this stuff, but those kinds of things don’t happen for people like us. You’re gonna end up working down the street, just like me. You’re gonna get your heart broken. Most of the people round here just end up in prison, so you might as well get used to the idea.”

So part of that is crushing, and the other part of it is: “Oh yeah? I’ll show you a thing or two.” I think I was able to hold my chin up and say: “I’m on a mission. I’m moving on. And if you look for me, there’s only going to be dust.”

You’ve said that you wrote your best songs in The Band after studying screenplays. Did films play a big part in your formative years?

Oh yeah. I was a movie bug from when I was very young, and from there it built and built. I became mystified by some of the extraordinary experiences watching movies, and wanted to know what was behind the curtain. That’s what drew me to wanting to read scripts. If I hadn’t have got so addicted to music at such a young age I would’ve ended up in movie land. I probably would’ve been a writer or a director.

Where did the love of music come from?

My mother was raised in a Six Nations Indian Reserve, then went to live with an aunt in Toronto at the age of six. So as a child, when we went back to visit, the instruments would come out and I would be exposed to all this music on the reserve. My parents bought me a small guitar and I would practice constantly. Then rock’n’roll suddenly hit me when I was thirteen years old. That was it for me. Within weeks I was in my first band.

You first saw Levon Helm drumming in Ronnie Hawkins’s band The Hawks. What did you make of them?

A local DJ in Toronto had booked my band to open for them. They were just the best rockabilly band around. I thought it was the most amazing thing I’d ever seen. When I eventually joined The Hawks, Levon was my closest brother, from the very beginning.

I was sixteen years old and Levon was like my older sibling, someone who knew the ropes and was from the Mississippi Delta. I mean, come on, this is the real shit here. Ronnie wanted to have the best band around, so he depended on Levon and I to help him choose the best young musicians out there. That’s how we ended up with Rick, Richard and Garth.

The documentary does much to underline the sense of camaraderie that existed in The Band before the fallouts later on.

Once Were Brothers was inspired by my book [Testimony], where I wanted to somehow get to the truth of that. I wanted to convey that feeling of this story of The Band. The documentary is really about the brotherhood, for the most part – the things that we went through to get to the point of where we were going. It was a crazy ride, an unbelievable ride. And a dangerous ride.

At the same time, there was a musical desire and a sound that we built inside of us. What we did – first with Ronnie Hawkins, then as The Hawks, then with Bob Dylan, and after with Music From Big Pink – didn’t sound like anything else. At all.

The Hawks backed Dylan on his infamous electric tour of 1966, when there was heckling almost every night. It was too much for Levon Helm, who quit midway through. Were you able to take any positives from that experience?

What was really enjoyable was when Bob and I would get locked into all of these things and sometimes we went into our own world. And with the rest of the guys too. We had these signals with the eyes, or maybe with me bracing the neck of my guitar at a certain point.

When we got locked into our own space, we could feel the magic in that. And it meant we had a barrier around the booing and all of this other stuff going on in the outside world. We were just in such a musical sanctum that we were unstoppable. Musically, we were bulletproof. So we had wonderful times, doing what we did. We knew that this was a tremendous rebellion, but we thought we were right. And time has proved that we were on to something.

How crucial was it to find the right conditions for recording Music From Big Pink?

I had this idea, this dream, and we just needed to find a place. It didn’t matter where, but one thing led to another and eventually we ended up in Woodstock because of Bob and [Dylan’s manager] Albert Grossman. When we got there we found this house, this sanctuary, and started to put Music From Big Pink together.

It was like a clubhouse, where we could shut off the outside world, and it was my belief that, because I knew these guys, something magical would happen. I knew their capabilities, I knew them inside out. And I thought I knew what was best for us. And some true magic did happen.

Can you remember the first time the magic happened?

It wasn’t so much of a moment, it was a growing period. In the back of my mind I was thinking about Les Paul. He had his own studio, he had his own place of creation where he had these tools. When you first hear records by Les Paul and Mary Ford you think: “Nothing sounds like that! This thing must be an interesting idea, because you’re not doing what you do in a formal atmosphere.”

It was a matter of going inside a cave and doing something that has nothing to do with anything except your own creativity. We had this basement down there at Big Pink, and an engineer friend of ours came in. He said: “This is going to sound terrible. You’ve got cinder-block walls and concrete floors and there’s a furnace over here. This is an awful place for sound.”

And again, like we were saying earlier, it made me feel like: “Oh yeah? Really?” We’d been working with Bob Dylan, so breaking the rules wasn’t anything new. We’d been breaking rules all of our life, where we’d played and the way we came up. I took Bob out there and showed him our little set-up and he got it in a second. He gravitated to it.

So it was this procedure of making our own sound in there, first as The Basement Tapes and then Music From Big Pink. It proved my theory that it could work. And at that time, with the exception of Les Paul, nobody was doing that.

What made you want to move from New York to Hollywood to record the follow-up, The Band?

It had nothing to do with Hollywood. There was a lot of snow in Woodstock and it was slowing down the process. So we thought how about we go somewhere where it isn’t going to be snowing and we can get the equipment, all live together and lock in again. So finding somewhere on the West Coast was just a convenience.

When we decided not to use a proper studio, Capitol Records in Los Angeles said: “This is the most ridiculous thing. Why are you doing this?” But because of the acclaim that Music From Big Pink got, I was able to use that to insist that this was something we just had to do. So they helped us get the equipment over to [legendary entertainer] Sammy Davis Jr’s pool house, where we could do this experiment.

You wanted to have a “woody, thuddy sound” on The Band.

Yeah, we’ve referred to it like that. We wanted to avoid the formality of normal studios, where they have these particular surfaces in there. Music From Big Pink came out pretty good, but we took it a step further on The Band, because there was no recording engineer and no studio at all. Again, when that record came out it didn’t resemble anything in the world. So it became something with its own identity and character. And that’s what I was shooting for.

We tried to shut ourselves off from the rest of the world all the way up to Shangri-La [the Malibu studio], when we made Northern Lights – Southern Cross [1975]. The Band was like a table with five legs that really stood strong and supported one another. And, as it says in the documentary, if one of the legs gets broken it doesn’t sit straight any more.

You wrote all of the songs on The Band, sometimes along with another member of the group, but you don’t sing any of them. What was it like hearing Levon’s spectacular vocals on The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, for example?

In making this record, I was casting these guys to play a part. I knew Rick had to sing The Unfaithful Servant, I knew Richard had to sing Across The Great Divide, and that Levon could only do The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. I wanted to write something that Levon could sing better than anybody else in the world. And I was right about that.

After addressing the subject in Testimony, has making the documentary somehow helped you come to terms with the difficult relationship that you had with Levon in later years?

That wasn’t an obligation of mine. I never had an issue with Levon. He had his own issues, and most of his issues were with himself. Sometimes he turned it on Rick, sometimes he turned it on Richard or Garth, and sometimes, later on – by that I mean ten or fifteen years after The Band wasn’t together any more – he turned it on me. And I wasn’t surprised by that.

I never even responded to it, because I knew Levon and the trip that he was on. He was having a tough time, and he blamed me. He was so great at playing and singing, but he wasn’t great at taking responsibility for stuff. It was his thing, and I didn’t really play a part in it, other than the fact that he pointed those arrows at me.

Another figure who looms large in your life, and most recently with The Irishman, is film director Martin Scorsese. Did the pair of you hit it off instantly when you first met in the seventies?

I just met him in passing to begin with. It was after he’d made Mean Streets [1973], and they did a screening of it for me. Afterwards he showed up to say hello. It was obvious watching that movie that there was talent lurking in there – the attitude, the use of music, Robert De Niro in one of his first real roles, everything that Marty did.

There was so much to be respected in his knowledge of film as well. Later on, when I asked him if he’d be interested in directing The Last Waltz, I realised that I really liked him.

I never had an issue with Levon [Helm]. He had his own issues, most of them with himself

Robbie Robertson

One of the songs on Sinematic, Beautiful Madness, alludes to the two of you sharing a bachelor pad.

We shared a house up in Beverly Hills, then we had a place in New York, a hotel suite that we shared for a couple of years. Were we a bad influence on each other? I don’t think that we were doing anything bad to one another. In our friendship and everything else, we were trying to look out for the other person. It’s just that we weren’t that good at it.

After Scorsese directed The Last Waltz, you threw yourself into feature films, writing, producing and starring in the 1980 film Carny. Was that an enjoyable experience, or a bit of a culture shock?

All of the above. Some of it was amazing and some of it was me biting off more than I could chew. There were a lot of things to overcome in that experiment. It was a tough combination: real-life carnies, real-life freaks, real movie people, actors, this whole thing. There were hugely conflicting lifestyles among all of these people. And somehow, in the midst of it all, I became the middle man.

Then after all of that I ended up doing music for the movie with Alex North, who was somebody that I thought was amazing [North’s film scores include A Streetcar Named Desire, Spartacus and Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?]. So the experience was phenomenal, but I didn’t know enough going in. It’s instinct. Sometimes you gamble on somebody and it works out, and sometimes it doesn’t live up to what you hoped.

It’s like with Once Were Brothers, where I gambled on this young director [Daniel Roher], who was only twenty-four when he started working on it. The producers thought I was crazy, but I said: “I’ve got a feeling about this and it’s what I want to do.” And because it was my thing, they couldn’t argue too much. So that worked out. But Carny was a combination of a lot of madness.

Is there a parallel to be drawn with The Band there too, in some ways?

There could be. Maybe I was still on the wavelength and I didn’t know it.

Do you ever ponder how The Band’s story might have turned out had addiction not taken hold?

To be honest, I don’t have a lot of time for pondering. I’m really busy and more concerned with working on what I’m doing today and what I’ve got to do tomorrow. I have such tremendous, deep memories of my experiences with these guys. But that was then and this is now.

Sinematic and The Band: 50th Anniversary Edition are both out now via UMG.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.