The Rutles: the strange and surreal story of the original Spinal Tap

Formed from the ashes of the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, The Rutles were a razorsharp pastiche of The Beatles with links to Monty Python and the Fab Four themselves

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Neil Innes would have liked to see the word ‘rutle’ in the dictionary. “As a verb,” he said, “meaning ‘to copy or emulate someone you admire, especially in music’.”

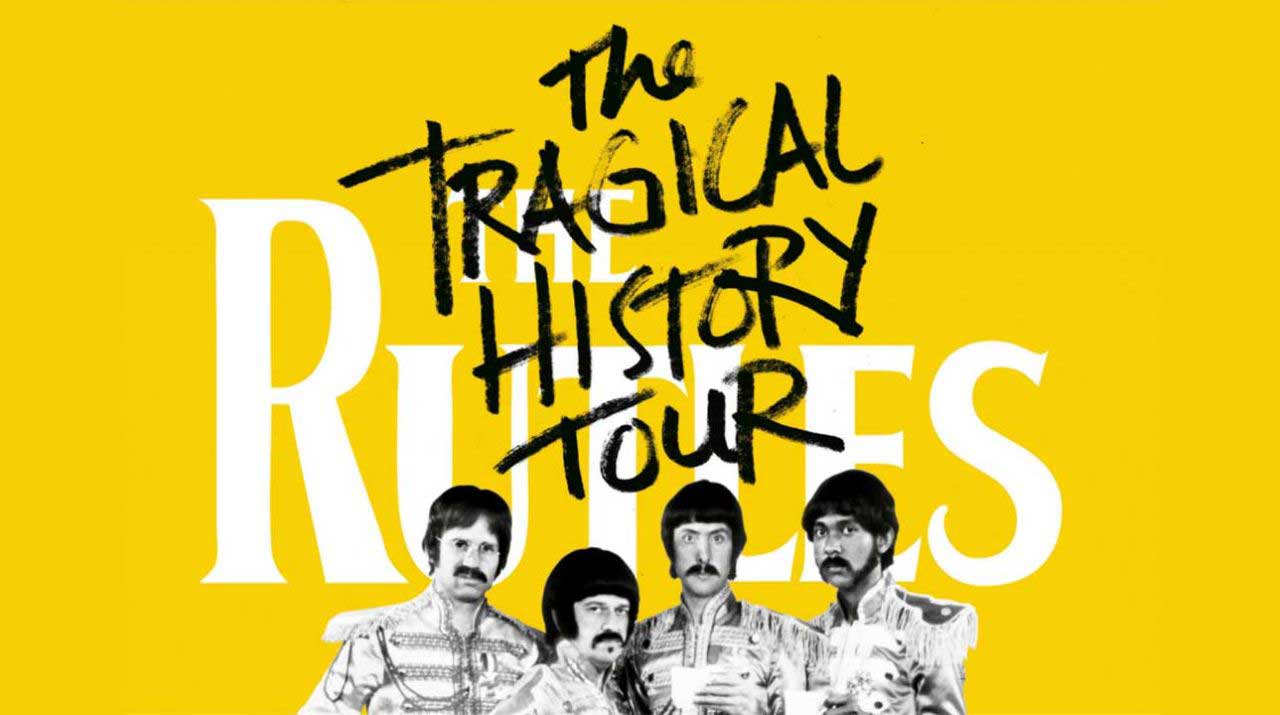

In 1975, Innes helped create The Rutles, a Beatles spoof for the BBC comedy series Rutland Weekend Television. Three years later, this make-believe band starred in the film All You Need Is Cash, a parody of The Beatles’ life and music. It included guest appearances by George Harrison and Mick Jagger, and later inspired This Is Spinal Tap. In May 2014, Innes revived The Rutles for a UK tour. Following the great tradition of rock reunions, it wasn’t be the original line-up, but that seemed somehow fitting.

Frank Zappa once posed the question: ‘Does humour belong in music?’ For Neil Innes, a man who poked fun at the medium with both The Rutles and satirical art-rockers The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and as the ‘seventh member’ of the comedy troupe Monty Python’s Flying Circus, the two were inseparable.

Shaven-headed and twinkly eyed when Classic Rock met him in 2014, Innes was an eloquent host. Yet in another great example of rock’n’roll tradition and life imitating art, the Rutles’ story has been blighted by lawsuits and clashing egos – just like a real band.

Innes helped create The Rutles in 1975, but the group’s roots reached back further. Like Pete Townshend, Jimmy Page and Keith Richards, Innes was an art student in the early 60s. By the time he graduated from London’s Goldsmiths college in 1965 he was performing with the Bonzo Dog DooDah Band, a group whose name was a play on the Dada art movement and who regarded themselves as the musical equivalent of Max Ernst or Salvador Dalí.

Their humour was offbeat and surreal, and their musical tastes reached back to the 1920s. The Bonzos recorded their own versions of what Innes called “songs from the age of The Great Gatsby and jitterbugging”, including I’m Going To Bring A Watermelon To My Girl Tonight and Hunting Tigers Out In India – which, he insisted, included “the best recorded raspberry of all time”.

Trad jazz, Elvis Presley and bubblegum pop were all parodied on the band’s 1967 album Gorilla, but the songs were often as well executed as what might be called ‘the real thing’. By the end of the year, the Bonzos had appeared in The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour film and on Do Not Adjust Your Set, a children’s comedy series starring future members of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. However, being ‘the real thing’ was never part of the plan.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“We thought we were being really subversive,” insisted Innes. “We had no ambition to become pop stars or appear on TV.”

The trouble was, mainstream success beckoned. By now, the Bonzos’ founder member, Vivian Stanshall, was a drinking partner of Keith Moon and Paul McCartney. When Stanshall complained to McCartney that the Bonzos’ manager, Gerry Bron, wouldn’t allow them sufficient time in the studio, McCartney offered to produce the group’s next single. Innes’s song I’m The Urban Spaceman, was inspired by post-war urban redevelopment and the space race. But its gentle satire also came with a cheerful sing-song melody.

McCartney co-produced the track, but only after teasing Gerry Bron (who would go on to manage Uriah Heep) by wasting the first 20 minutes in the studio playing a ditty he’d written the night before. “He said: ‘The Beatles haven’t heard this yet’,” Innes recalled. “Then proceeded to take forever winding up Gerry playing this dirge, Hey Jude.”

I’m The Urban Spaceman reached No.17, turned the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band into pop stars and earned its composer an Ivor Novello award.

“I didn’t realise what an honour it was,” admitted Innes. “I’m afraid I ended up using it as a doorstop.”

By 1970, the Bonzos had run out of steam, just like a ‘real’ band. “We hadn’t had a holiday in five years, we’d paid off three managers and we were all knackered.”

Innes formed a new group, The World, and made an album of Beatles-inspired rock titled Lucky Planet. The humour was subtler, but he couldn’t adjust: “Before we finished making it, I knew I’d gone too far down the conventional route.”

The World’s drummer, Ian Wallace, who’d refused Innes’s requests “to play a simple ‘boom, boom, crack’”, went off and joined knotty prog rockers King Crimson, “where he could go ‘boom, crack, boom, crack-boom’.”

Meanwhile, Innes took a phone call from Monty Python’s Eric Idle, and ended up appearing in Python’s third series, contributing songs such as The Most Awful Family In Britain. When Monty Python played their First Farewell Tour in 1974, Innes was part of the cast and played the piano between sketches. He toured again with Python in 1976 and ’82.

It didn’t take long for Innes to discover that Monty Python were just like a rock group, with the same delicate mix of egos and talent, from which John Cleese now emerges as the resident Roger Waters.

“Cleese left twice,” revealed Innes, “because he got fed up of arguing with Terry Jones. Terry used to drive John nuts.

“I was shocked at first because of how much they tore into each other,” he added. “We were in a railway carriage once, and it kicked off. Then John noticed my horrified face and said: ‘Look, Neil. We have this thing called ‘stick’ and we whack each other with it.’ Nobody was spared.”

On tour, Innes found himself mediating, just as Ronnie Wood would do in the 80s with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards in the Rolling Stones. “Every one of them would come to me about some problem and I’d say: ‘Look, you have to take the bigger view. I know, because I’ve been in a band…’”

It was all grist to the mill for when Innes and Eric Idle created The Rutles for Rutland Weekend Television, a Python spin-off sketch show about a low-budget local TV station. The Rutles were Ron Nasty, a pastiche of John Lennon played by Innes; Eric Idle was Dirk McQuickly (McCartney); session drummer John Halsey became Barry Wom (Ringo Starr); and TV actor David Battley was Stig O’Hara, based on George Harrison.

Innes wrote I Must Be In Love, a song that sounded like a 1965-era Lennon & McCartney composition, for a sketch that spoofed The Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night, and The Rutles were born. But what gave them a life was the sketch being transmitted later on America’s NBC Saturday Night (soon to become Saturday Night Live), a satirical comedy show whose clued-up audience were familiar with the cult British comedy Monty Python’s Flying Circus. As a vehicle for comic actors such as Dan Ackroyd, Bill Murray and John Belushi, “Saturday Night Live was the flagship satire show”, said Innes.

In January 1976, US concert promoter Bill Sargent offered The Beatles $50 million to reunite. A few months later, fellow promoter Sid Bernstein placed a full-page advert in The New York Times offering them $230 million to re-form for a one-off charity concert. “So Saturday Night Live had this running gag about The Beatles reunion story,” explained Innes.

In April, the show’s producer, Lorne Michaels, appeared in a sketch where he offered The Beatles $3,000 to reunite. “All you have to do is sing three Beatles songs,” he said. “‘She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah…’” That’s $1,000 right there. You know the words – it’ll be easy.” Apparently, Lennon and McCartney watched the programme in Lennon’s New York apartment, and even considered turning up at the studio for fun.

At the time, though, McCartney’s post-Beatles group Wings had just enjoyed a US No.1 album with Wings At The Speed Of Sound. Although McCartney, Lennon and George Harrison had all contributed songs to Ringo Starr’s new solo album, Ringo’s Rotogravure, there would be no reunion. “As of now, no Beatles!” an exasperated Starr told the press. “We just don’t need it.”

However, George Harrison gamely appeared on NBC Saturday Night in a skit in which he accepted Lorne Michaels’s offer and tried to keep the $3,000 himself. Shortly after, Eric Idle kept the gag going further by appearing on the show. “The joke was that Eric couldn’t get The Beatles, but he could get The Rutles for three-hundred dollars,” said Innes. “So they showed The Rutles sketch from Rutland Weekend Television.”

The clip of The Rutles performing Innes’s I Must Be In Love prompted an incredible response. “The mailbag the following week was ludicrous,” he said. “People were sending in Beatles LPs with ‘The Beatles’ crossed out and ‘The Rutles’ written instead.” Innes was convinced that this astonishing reaction was driven mainly by the American public’s desire for a Beatles reunion and their willingness to embrace a little make-believe.

“The Beatles were never going to get back together,” he said. “But The Rutles allowed the American public to pretend and to play a kid’s game, with air guitars or cricket bats as guitars. It was getting so silly with these Beatles reunion offers that someone needed to do something sillier.”

A year later, NBC had stumped up the money for Innes and Idle to make All You Need Is Cash, a film telling The Rutles’ story. “You could never do something like that today,” said Innes. “Put together an idea on a couple of sheets of A4, give it to a TV programmer and say: ‘We want to do this.’ It wouldn’t happen.”

Stranger still, after getting the money from NBC, Eric Idle persuaded Harrison to appear in the film. “There was a social connection between George and Eric, but it went deeper than that,” maintained Innes. “George was the first one to leave The Beatles and it was very painful for him. He thought there was a sunnier way to tell the story.”

If Harrison thought The Rutles would present a sugar-coated version of The Beatles’ tale, then he was mistaken. Harrison authorised The Beatles’ ‘fixer’, Neil Aspinall, to provide Innes and Idle with the candid interview footage that later turned up in 1996’s The Beatles Anthology.

When it reached the part where Beatles manager Brian Epstein died from an accidental drug overdose in 1967, the story went downhill. “We both suddenly went, ‘Oh,’” admitted Innes. “Because after that they all start suing each other and the story becomes a tragedy. We had to make it funnier, because people didn’t want to believe that was how The Beatles had ended.”

Despite Innes’s belief that “The Rutles made The Beatles’ story nicer than it was”, what makes All You Need Is Cash such an enduring film is the way it skewers the pretension and absurdity of the music business. Innes and Idle also didn’t flinch from parodying every aspect of The Beatles’ story and its many characters.

Brian Epstein, the homosexual former record shop manager who became The Beatles’ manager, was the inspiration for The Rutles’ Leggy Mountbatten, “a retail chemist from Bolton who’d lost a leg in the closing overs of World War Two” and who was attracted to the band because of their tight trousers.

Meanwhile, Epstein’s successor, hard-nosed US businessman Allen Klein, who would later serve jail time for tax evasion, ‘became’ Ron Decline, played by John Belushi. “Anyone was free to inspect his books,” claimed the voiceover, “but no one could find his accounts.”

For the film, The Rutles replaced their original ‘George Harrison’, actor David Battley, with former Beach Boy Ricky Fataar. Innes, meanwhile, wrote an album’s worth of songs that spoofed every Beatles era: from the sunny beat pop of Help! (in The Rutles’ case, Ouch!) to the 12-bar blues rock of Get Back (Get Up And Go), via A Day In The Life’s saucereyed psychedelia (Cheese And Onions).

Innes, Fataar, John Halsey and guitarist Ollie Halsall (Halsey’s bandmate in the prog-rock group Patto) performed the music on the soundtrack. But although Idle ‘played’ Paul McCartney – or rather The Rutles’ Dirk McQuickly – he didn’t sing or play on any of the songs – something that would later contribute to the friction between him and Innes.

All You Need Is Cash also included cameos by Paul Simon, Ronnie Wood, Mick Jagger and his then wife Bianca, who played McQuickly’s fabulously haughty wife Martini. “Bianca was supposed to be a terrible cow,” said Innes, “but she turned out to be an absolute darling.” George Harrison, meanwhile, appeared as a TV journalist reporting on the demise of Rutle Corp, a parody of The Beatles’ ill-fated Apple boutique and record label.

NBC broadcast All You Need Is Cash in March 1978, where it became, said Innes proudly, “the lowest-rated show ever to be shown on prime time.” Part of the reason for its failure was precisely because it was broadcast during prime time. Winning over NBC Saturday Night’s hip audience was one thing; competing with an episode of the hugely popular Charlie’s Angels was another.

“You can imagine how The Rutles must have looked on a TV set in Illinois,” said Innes. “But who remembers that episode of Charlie’s Angels now? I’m proud of the fact that it’s still the lowest-rated show, though it’s probably made up for it since.”

All You Need Is Cash failed to win over Middle America. But it won over The Beatles – almost. Innes isn’t entirely sure. “George was always on board,” he said. “John was the next Rutles fan. Ringo has always been diplomatic about it, but probably had a moment or two because of some of the drummer jokes.”

Which just leaves the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band’s former producer, Paul McCartney.

“Every time I’ve seen Paul, he always gives me a hug and there’s no problem,” said Innes. “But I heard that he didn’t like Eric’s portrayal of him.”

Idle’s Dirk McQuickly captured every one of McCartney’s mannerisms, from the startled eyes to the head tilted coquettishly to one side. “I don’t think Eric meant any harm… but I do think perhaps Paul lays himself a bit open to it.”

In the end, it was The Beatles’ publishers, ATV, who bit back. “John Lennon advised us that we might have trouble with Get Up And Go because it sounded so much like Get Back,” sighed Innes, “so we left it off the album.”

ATV lodged a lawsuit anyway, which Innes eventually settled out of court. As a result, 50 per cent of his royalties for the 14 songs on the All You Need Is Cash soundtrack went to ATV. Meanwhile, Lennon and McCartney’s names were added alongside Innes’s on some of the songwriting credits.

“It’s brutal,” he said, his smile fading for the first time. “I couldn’t afford to get a lawyer that would go up against these big corporations. They’re like the banks – they’re too big to fail.”

Innes maintained that he didn’t analyse The Beatles’ music before writing The Rutles’ songs, but instead wrote everything from memory. “I knew I would be sunk if I went and listened to those songs. It all had to come out of my head.”

After All You Need Is Cash, Innes starred in his own TV show, The Innes Book Of Records, and had a small role in Monty Python’s Life Of Brian. At the film’s wrap party, he recalled John Cleese subjecting fellow Python Terry Gilliam to a prolonged and ferocious bollocking. Innes tried to intervene.

“And after the third time, John told me to fuck off,” said Innes, who seized the moment by quoting some dialogue from the film: “I replied: ‘How should we fuck off, oh Lord?’”

In the 1980s, Innes worked in children’s TV, and later made documentaries and radio programmes. After Monty Python played the Hollywood Bowl in ’82, Innes found himself at a party at Steve Martin’s house. Among the guests was the comedy actress Estelle Reiner, mother of actor and director Rob Reiner: “She introduced me to her son and told me he’d just made an excellent rock’n’roll film,” Innes recalled.

That film was the spoof ‘rockumentary’ This Is Spinal Tap, released two years later. “I fell about like everybody else when I saw it,” said Innes. “And I love that The Rutles was an influence on it.”

Innes and Idle revived The Rutles sporadically. A second, rather patchy, film, Can’t Buy Me Lunch: Rutles 2, emerged in 2002. “I persuaded Eric we should do it,” said Innes. “Then Eric emailed me and said: ‘I’m a one-man band on this, alright?’”

The relationship between the two founder Rutles later deteriorated to Saxon versus Oliver/ Dawson Saxon levels. “We don’t get on,” admitted Innes, smiling again. “We’ve drifted into a mutual irritation society. Eric expects the people he’s helped over the years to do as they’re told, and he’s remarkably selective with his memory.”

Innes took this new version of The Rutles out on the road without Idle’s blessing. Only drummer John Halsey remained from the original line-up. The rest of The Rutles 2014 were made up of Innes’s long-time musical collaborators, bassist Mark Griffiths, guitarist Ken Thornton and former Camel keyboard player Mickey Simmonds.

“There’s no costumes or wigs, though,” insisted Innes. “That was in the film. This is all about the songs.”

Ultimately, you couldn’t help wondering whether a songwriter capable of composing such expert pastiches wouldn’t have been happier as a ‘real’ pop star. But Innes said: “I’m not really in this business. I don’t like the idea of deifying people just because they know how to play three chords.”

Innes viewed the high-production Monty Python reunion shows at London’s O2 in 2014 with the same scepticism as he did for bloated rock bands re-forming for a quick buck. He preferred the accolade of having made a film that remains a tour-bus favourite.

“Most guys who play music and get in a van have to have a sense of humour to do it,” he said, “and you have to keep that sense of humour. George Harrison used to say: ‘It’s all very well being rich and famous, but if you’re lucky enough to become rich and famous you still have to work out who you are.”

Neil Innes, you suspect, knew exactly who he was.

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 197, in June 2014. Neil Innes died in 2019.

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.