“We were the antithesis of Britpop – we really hated all that kind of thing." Every Idlewild album in the band's own words

Scottish rockers Idlewild are poised to celebrate their 30th anniversary with the release of their self-titled 10th album. Frontman Roddy Woomble talks us through the history of the band, album-by-album

It was when his band first appeared on Top Of The Pops that Roddy Woomble realised a life in the spotlight might not be for him. The Idlewild frontman had grown used to his status as the lead singer of a beloved cult band, and had become comfortable enough with the intense gaze of a small but dedicated fanbase that generally follows. But once the cameras turned on him, he felt that gaze begin to widen. “It was our first experience of TV,” he tells Louder. “Before, I would be able to wander around and maybe people following music would know who I was, but that was no problem, because they were music fans.

“But suddenly you're on Top Of The Pops and you're in like the supermarket, and people are staring at you. I didn't enjoy that. It made me think, ‘Maybe this is not a good idea’.”

If you’re familiar with Idlewild’s back catalogue you’ll know it’s one which can stand toe to toe with those of most British rock bands and, in many cases, emerge victorious. Formed in Edinburgh in 1995, in an effort to kick back against the mindless blokiness of the emergent Britpop scene, Idlewild were fed on a diet of American hardcore and college rock – a teenage stint in the US introduced Woomble to the likes of the Replacements, Minor Threat and Black Flag, who he eventually imported back to his Pavement and Nirvana loving bandmates – and inspired to create something that captured both the sophistication and raw energy of their US counterparts.

“We were really the antithesis of Britpop – we really hated all that kind of thing,” says Woomble. “So it was a bit of a reaction against all that, we wanted to make something that had a sort of romanticism, lyrically, but at the same time was really quite noisy and chaotic. The American underground rock scene was really artistic, really uncompromised, but at the same time really exciting and also quite often really catchy. Fugazi and all those bands I just mentioned were really good songwriters. They could write really great, memorable refrains and hooks – it wasn't obscure in that way.

“We never wanted to be an obscure band. We realised quite quickly we had a real talent for writing melodies and catchy bits.”

Those catchy bits did the trick. After building a fanbase through relentless touring and resolutely doing it themselves, they eventually signed to a major for their third album, The Remote Part, and went into the UK album charts at number 3. The band were poised to become British rock’s next big world-breaking export – which, of course, is when everything began to fall apart. Band members left, the music industry itself began to come apart at the seams. But when Woomble talks about Idlewild’s brush with the bigtime, it’s not in terms of missed opportunities or a career that could have been – even if that’s how other people can sometimes interpret it. “There's lots of people that used to say that Idlewild should have been big, or this, or that,” he says. “But at the same time I think that maybe it worked out better for us that the spotlight moved off us. We managed to become a far more interesting band when it did."

30 years on, Idlewild are on the cusp of releasing their 10th album – a celebration of the band’s three decades together, and one which is self-titled to acknowledge the fact that “it encapsulates a little bit of everything about all the other records that we made together.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

“The band have been around for 30 years, and we've made a brand new record which is really strong,” he says. “It's like a real celebration to be together and still be making music together 30 years after we started doing it.”

“I'm actually quite proud, in my own way, that we've managed to stick around so long.”

Here, to celebrate 30 years of Idlewild and the release of their new album, Woomble talks us through each of their 10 albums one by one.

Captain (1998)

Idlewild formed in 1995, and at that point bands like ours didn’t have any money or anything behind us. There was no access to recording studios, so we basically just played live for about a year. We’d never worked on covers – we always just did original material – and quickly we got a reputation for chaotic, noisy live shows.

This translated eventually to the fact there was a local label called Human Condition Records, and they were run out of Chamber Studios in Edinburgh. Jamie Watson, who ran the label, wanted us to record a single [Queen Of The Troubled Teens]. It was our first time in the studio, so it's not a great sounding song because we were used to playing live, and that instant response. The minute you don't get that when you're recording, it's really difficult.

But the single came out and we were kind of blown away by the fact it was getting played on the radio. [Ex-NME journalist] Steve Lamacq, who had a Radio 1 show called The Evening Session, was the first DJ to play it. Because we were a bit naive about all, we just posted him a copy of the single – you know, an envelope to ‘Steve Lamacq, BBC’. We didn't put much information about ourselves in it. He played it on the air and said, 'If anyone knows anything about this band, can you get in contact with me?' So we did – we sent him a fax, because this was before emails, and things spiralled from there.

We did another seven inch single with Fierce Panda, and Steve Lamacq was involved in Deceptive Records, another independent label, who put out Elastica's stuff, so we agreed to do another single with them. Then it just morphed into, 'Why don't we just put all our best songs on it and call it an album, or a mini album?’

So that was the genesis of Captain. In the late '90s a lot of bands were being signed for a lot of money, and recording a record, but then the records weren't being released. It was almost like labels used to collect bands because they didn't want other labels to have them, and we were determined not to go down that path. We'd established ourselves a wee bit already by the time labels were really interested in signing us and had put ourselves in a really good position. That's not because we had particular careerist notions – far from it. We were interested in making up cool songs and playing them live, that exchange of ideas and the things that we got from bands that we went to see. But obviously, when the opportunities came along, I couldn't believe the first time I got a cheque for, like, 800 quid or something, and I could pay my rent and live off it. I was thinking, This is actually just from playing in a band!

Captain is very much an introduction to the band, and it still has a sort of power about it. It was recorded so fast, and so cheaply, and we were so new in the studio, that there's not much sophistication to it. But you get a really good idea of what the band was all about at that point. There were lots of possibilities within that the sound at that time.

Hope Is Important (1998)

We wrote and recorded Hope Is Important in between tours. It was mainly done in a studio in Lincolnshire called Chapel Studios, which is a residential studio. So we'd basically be on tour, then go and record for a week, and then go back on tour. We were rarely at home that year, and the record suffered slightly from that – there wasn't lots of consideration, we were literally just thinking ‘This song sounds cool, let's record it’. So we’d record it, wouldn't analyse it too much, and then go away on tour again, where we’d try and write a few more songs

We finished it in Dublin, actually, at Pear Street studios because it was cheap to use at the time. We knew it was a record on the way somewhere, but we hadn't got there – which is one reason why we called it Hope Is Important.

On the front cover I put one of my photographs of two of my friends looking at a rotten boat on the beach that's been washed up. There's two young people looking at this decayed thing, just wondering how even though it's never going to be pieced together again, it still exists with them – it's that idea of the past and the future and the present time. I think that's what I was getting at with all these songs like A Film For The Future and 4 People Do Good. Obviously there's naivety to my work at that point, because I was still quite new to writing words and stuff. But I think I was trying to get that it was a record about being young – obviously, we were all just out of our teens when we recorded it. It's got that feel that you can't really replicate unless you are young. We could never go back and write songs like tha, it would be really weird if we tried to.

It was also a record for young people, because most of our fan base were our age or younger. So that's why it's probably the most nostalgic record that we've got. When we play songs from it, there's people in the audience that were teenagers when it came out, and suddenly, it relights their youth, and they're teenagers again for the duration of the song.

It was a transitory record, going between Captain to something where we were developing our songwriting quite quickly, at a good rate of knots. And the label were really supportive of us. It was quite well received. There were a few bad reviews, but generally positive.

It did pretty well – When I Argue I See Shapes was in the Top 20 back when that was more of a big deal than it is now. We went to America and Japan and places like that, and we really did find ourselves thinking ‘Well, one, we're a proper band. Two, we really need to take this seriously, because there's millions of other bands, and if we're going to make another record, we need to kind of make sure that the songs get a bit better’. I think the leap between Hope Is Important and 100 Broken Windows is probably the most significant one that we made as a band.

100 Broken Windows (2000)

We put a lot of internal pressure on ourselves with this one, and there was a wee bit of a pressure from the label, but nothing significant. Everyone knew that they wanted the record to be more popular because it was like a major label – Parlophone, MRI. Our labelmates were Radiohead, Kylie and Blur; it's not a label for underachievers. Songs like A Little Discourage and Roseability and These Wooden Ideas had loads of hooks and lots of interesting, thoughtful lyrical refrains. We tried, we did try.

We started off recording it with Bob Weston from Shellac and were indulging our fantasies a little bit of all these American underground records he was involved with. It was a really amazing experience to record with him, but ultimately it produced something that the label weren't really interested in. So we got in touch with Dave Eringa who, at the time, had worked with Manic Street Preachers and lots of other bands. We started a relationship that continues to this day. The minute we met him everything clicked. He was just a wonderful guy who really understood what we're trying to do, and really, really helped us develop.

Sonically, 100 Broken Windows is a big, significant step from Captain and Hope Is Important. Everything - the melodies, the harmonies, the guitar sounds, the textures, stuff that we'd never really thought about - suddenly he was helping us get all that. That's why we’ve worked with Dave on pretty much all our records, and even when we don't work with him, we send him recordings and see what he thinks. He's a real part of the group, and the group's history.

We actually finished it off with Bob Weston in Chicago at Electrical Audio Studios, which is Steve Albini’s studio. We were going to go on tour in America, so we went over and spent a week there. There's a couple of songs on the record from that session, so there’s a real lovely mix against Dave’s stuff on this, because [Bob’s tracks] have still got a rawness to them, and an energy that's different from the stuff that Dave produced, which is a lot more melody-driven.

It’s one of those records you can't really plan. Everything just came together when it was supposed to, and because of that, it’s got a bit of magic to it. I think that's why it's an Idlewild fan favourite. The album artwork as well, it all works in with the romanticism of it, and mentioned things like post modernism and Gertrude Stein – all this kind of thing mixed in with riffs and distortion. It's still got youth, because we were 22 or 23 by this point, so still young, but we were starting to get a bit wiser about the world, and our place within it. It was reflective enough for people who were a bit older than us to now get into, so we weren’t just seen as a band for teenagers and started to be considered more as a legit British, Scottish rock band who’ve been around for a while and are getting better.

Suddenly we get a lot more press interest, and the record goes into the Top 20. We go on Top Of The Pops with a song about post-modernism, and started being on magazine covers, unlikely rock stars. It's a really significant record in Idlewild’s history, and probably one of the best things we've ever done.

The Remote Part (2002)

The Strokes and White Stripes and all the American bands that came over in 2001 really ignited people's interest [in alternative music] again. Partly because 100 Broken Windows was a bit of a hit in America, we ended up doing a bit of touring there, and meeting quite a lot of these bands, so we were weirdly more aligned with that than with a lot of British bands that came around.

It was at this point that everything had come together: it was the most popular that we've ever been commercially, certainly, with all the press and the TV and all the stuff around the record being released, and The Remote Part went into the charts at number three; Oasis, then Red Hot Chili Peppers and Idlewild. It was quite surreal in that way, suddenly, to be in that position – basically a mainstream band, but with the attitude that we weren't, and still not able to perform the way that a mainstream band would perform. Which is probably one of the main reasons why we were probably not as popular as we could have been. We just didn't care enough about the performance aspect of it.

Around the time of The Remote Part we opened for Coldplay on tour. Coldplay were on the same label as us, and they'd been signed after us. They actually supported us once as a fellow Parlophone band, and even then I was thinking, These guys are really pro, they really know what they're doing. And then on that arena tour, when it was Idlewild supporting, they were just… a fully formed arena band. And that had happened so quickly, and it was obviously the professionalism and their attitude towards live performance, and their ambition.

Idlewild just didn't have that focus: things were still breaking onstage and we were still falling over. I remember playing on an arena stage and people were just a bit like, What's this? Then you'd play a song they knew, like, American English, and they'd be like, ‘Oh, that's good’. But we just didn't have it together, all the elements weren't in place for us to be accepted by the mainstream. Even though the music got played on the radio and the songs were gaining popularity, there was too much of an outsider attitude to it. The man in the street doesn't really like that – he wants something presented to him in an exact way. That's when I realised that maybe weren't really going to get any bigger than that. It wasn't the fault of our songs.

The Remote Part was also where we had the first lineup change when Bob Fairfoull [bass] left the band, and Gavin Fox joined, and Allan Stewart joined as a second guitar player.

Not to blame Bob, but he was definitely quite an erratic personality and quite an erratic musician. That brought a certain punk rock attitude to things, which was amazing when we were playing clubs, but when you get on bigger stages it doesn't translate when the rest of the band aren't doing that. So it caused a bit of conflict in terms of artistic direction.

Eventually he left the band midway through our biggest ever tour. It wasn't ideal, and that was another reason why things didn't go really according to plan. We had to regroup, and spent a lot of time in the Highlands of Scotland in an old house there, recording what was to become Warnings And Promises.

Warnings/Promises (2005)

We'd signed to Parlophone for four records, and we knew that they weren't going to re-sign us because we weren't as popular as they wanted us to be. But also we could just see that the industry was changing, with Napster and streaming. Loads of our friends at the label were starting to get made redundant and it seemed like every second month things were developing in a different way. So it actually worked for us in a way; we finished a record deal and we walked away having benefited massively from being on a major label -with all the tour support and all the fans we gained through their promotion and help - into a position where we were basically an unsigned band again.

We all took some time off, and I made a solo record and started working on music with different people. We didn't find it difficult to get re-signed because we were quite a popular band, but we signed to an independent label to make Warnings/Promises. But within six months that label had folded because of all the changes. And then we started realising, ‘Wait a minute, no one really knows what's going on here, so we can probably put a record out ourselves now’. That's when a lot of bands that had been around for a while started doing that, started just using distribution and making the music themselves. So that was also a big change artistically, because before that, a lot of music you’d hear on the radio, the bands had to go through the process of the label, the A&R, have all these people commenting on the songs, to get the songs to one place. Suddenly bands are just doing things themselves, nearly like the late '80s DIY scene again. You're answer to no one, you're just putting out the music that you want to put out.

Following the success of The Remote Part, there was a little pressure on us. We went up to the Highlands again, and we wrote 40 or 50 song ideas. We started recording them with Dave Eringa in Sweden at a cool studio, Tambourine Studios in Malmö. We recorded six songs, and the label were like, ‘Nah, we don't really like where you're going with this’. So they suggested Tony Hoffer, who was an American producer who’d just worked with them on Supergrass and Air. They wanted us to make a different sounding record, and obviously we wanted to do that too – we were never interested in making the same record.

The thing about Tony that was very appealing was he worked out in Los Angeles, at Sunset Sound, which is a legendary studio for a music fan. So we all went over to LA for two months. It was just glorious. It was such a memorable, wonderful experience. We all knew that we're probably not going to make another record on a major label, so we just thought, ‘Well, we may as well use this budget and have a great time’. It was one of the best times in my life, really, just waking up in the morning and driving a hire car to Sunset Boulevard, recording at Sunset Sound, and then in the evenings we just made loads of friends, loads of bands, hanging out, partying and having fun and just living a life that was very temporary and wasn't a true reflection of what most people experience in Los Angeles, which is full of massive divisions of poverty and wealth. We were just dipping into a rock fantasy... and it produced a really good album too.

We were still quite serious about what we were doing, but I think the laid back way we were approaching and recording this is all over that record, and it's quite a different sounding record to The Remote Part. Maybe it was too different- sounding for people in a way, we got a wee bit of a backlash, saying there's too many acoustic guitars and it's too much like this, or too much like that. It was maybe seen as a move too far, like we were trying to be something different but Idlewild were always trying to be something different. That's the whole point of creative collective work; it's not to do the same thing.

It's one of my favourite Idlewild records and by any standard nowadays, it did really well. It sold 200,000 copies and went into the [UK] Top 10. I look back at it with fondness and reflection. I'm not bitter in any way about anything, I think it was a wonderful experience.

Make Another World (2007)

With Make Another World we wanted to basically recreate what we'd done before, It wasn’t a backlash to Warnings/Promises, that's too strong a word, but certainly we wanted to reference earlier records.

We recorded it in our practice room outside Edinburgh, and we made it in two weeks. So it had that spirit that Hope Is Important and Captain had – you weren't lingering over things, you were literally finishing writing the song, recording it, and it's for that reason I quite like it. David Eringa came and produced it in our practice room, so it does have a slight punk rock vibe about it. But at that point we were a band who could linger over things and make them more interesting, we had that ability, so it maybe suffered a wee bit from that of attitude of like, ‘No, that's fine. It sounds fine’. Rather than say, ‘Maybe we could add this’, or ‘Maybe we could do this differently’, which is what we doing previously on records like Warnings/Promises and The Remote Part.

It was a kind of a statement. It was supposed to be referencing ourselves for the first time, because we realised that we were a band that had a sound. It’s a wee bit like the new record, to be honest – we feel a bit empowered by what we've done; there's a pride going through that.

I remember at the time I had lots of theories about the songs, which I can't remember anymore. Now I just listen to it as a record. When you make records, you're thinking about the songs a lot, but the minute they're out, they belong to other people. You don't really think about them again.

Make Another World was always weird because people called it return to form. But I thought the record we made before was actually better [laughs].

Post Electric Blues (2009)

The label that Make Another World was on was no more, so again, we were unsigned. So we make a record ourselves. Rod Jones our guitar player is pretty proficient at recording and David Eringa was involved as well. We recorded again pretty quickly. Nothing was too lingered over.

The record is probably – not to be dismissive of it, because people do like it – but probably the weakest Idlewild record we've made, I think. The first three songs I think were really strong, it had a really good opener, but towards the end of the record, there's some songs on there that I don't think we would have taken beyond demo stage around the time of The Remote Part. It felt very much like a working band at that point, which was never really the the way we viewed the band. We viewed the band as an artistic thing, rather than as a thing that helped you pay your rent.

It started to feel a wee bit like that for everyone, not just for me, and at this point everyone branched into doing different stuff. I had quite a few solo records, Rod had started getting into recording and was really wanting to try and build his own little studio and work on that kind of thing. Everyone had started working with other bands as well, and after we'd finished the tour for that record, it really felt like a good time to not do the band anymore for a while, because it really felt creatively, we didn't really have a direction, and everyone's attitudes and priorities were in different things. It was no longer the main focus.

Even the title, Post Electric Blues, is a bit melancholy. It was after I'd started making acoustic records, and someone had said to me, ‘Don't you want to be a rock band again?’ and I said something like, I think I just have post-electric blues. So it was just this whole weird time for the band: it wasn't negative, everyone still got on and still really enjoyed playing gigs, but it felt like the creativity drained out into other things. Life had also taken over in that way that everyone was now in our early 30s with families and that kind of thing. It wasn't a situation where we thought that we would never see each other again or make music again. It just felt like, let's just see what happens over the next few years.

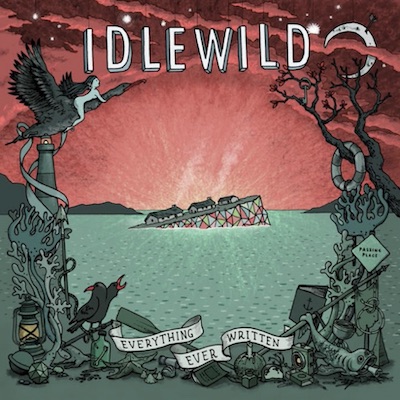

Everything Ever Written (2015)

What happened with Everything Ever Written was really very, very natural. We didn't see much of each other for a couple of years – we kept in contact via emails and things like that, but the band was basically put on the shelf. Everyone got on with different things. Idlewild have never lived in the same place for years; Rod is the only one that still lives in Edinburgh. Everyone else moved to different places, and now we're all over the place, from London to the Hebrides. So everyone went to their own corner and did their own thing.

When me and Rod started working on songs for Everything Ever Written it was just the two of us, and it felt like starting again the way that we'd done when it was just the two of us back in 1995, when we were in his bedroom coming up with songs. So that's what we did, me and him just got together until we had about 10 or 15 ideas that we liked – and then Colin (Newton, drums) got involved, and the three of us fleshed out a lot of these ideas.

At this point, Allan and Gareth (Russell, bass), they were doing different things, working with other bands and stuff, so they weren't going to be involved in this record, and so we needed to find new members. Then Lucci (Rossi, keyboards), who was a friend of mine, joined, because we decided that rather than go down the two guitar approach, we'd have just Rod playing the guitar like at the beginning. Lucci is a brilliant musician - he's the only musician in Idlewild that's ever been trained - so he just straight away added different things.

That was a really good thing, because the familiarity is the fact that we've made lots of records together, and people like that sound of the combination of me and Colin and Rod together, but there's a new element with Lucci bringing something different to it. So when we all got on board with it the record came together really quite quickly, even though it was probably about a year and a half of just working on ideas in various places.

Andrew Mitchell joined towards the end as our bass player. And then suddenly we were a band again, and we found ourselves in a position we hadn't been in for the years previous, with the last two records, that people were really excited about hearing our music, and it was getting played on the radio, and the tour sold out. It almost felt like people had missed us!

Interview Music (2019)

I suppose the whole infrastructure of how we worked had changed quite a bit, because from 1995 to 2010, that was 15 years we were a full time band, all of us working for the band – our focus was just on that. But after the break it was just not like that anymore, in terms of how the band meant something different to us all now. Everyone had diversified and was doing different things and working on different projects, artistic and otherwise, or just simply being parents. It felt in many ways more special and when we actually focused on it, we produced really great things.

We actually started work on songs for Interview Music quite quickly after Everything Ever Written, and we recorded some of it just after we did some American dates in 2016, when we spent 10 days in the studio in Los Angeles and recorded probably about five or six songs.

It wasn't until we did the gigs for the 15th anniversary of The Remote Part that we really brought the focus back into the band. Playing that record in front of people that love that record really made us realise that our music has soundtracked a lot of people and their growing up and that made us want to finish the album. You can see this recurring theme of us pondering for ages, losing track of what we're doing, and then suddenly something clicks, and we focus on it, and then it works, actually quite fast.

Dave Eringa was a bit of a catalyst to Interview Music because he got involved on that record and really made us finish. It was the longest record we've ever made. It's 13 songs, and it's got little ambient bits between the songs, it's probably the most experimental thing we've done as well. I really like it, and I don't think it got the attention that it maybe deserved.

Idlewild (2025)

The songwriting for this started straight after Interview Music, but it was stopped for basically two years, due to the pandemic. During that time I made several solo records and started touring solo again when we were allowed to tour, and that was mainly my focus.

But when we did The Remote Part 20th anniversary shows, we decided 'Let's write some songs'. We did that in 2024 in several songwriting sessions, some up here in the Hebrides and some in Edinburgh at Rod's studio. We just got a group of really good songs together. And then at the start of this year, we just spent two weeks in Rod's studio recording them. He produced it and mixed it.

We didn't linger over the recording too much, but we did spend a lot of time on the songwriting, and I think you can really hear that. I think the songs are really well constructed, and they have a lot of things that like people like about Idlewild, I think. There's lots of really catchy melodies and great guitar parts, and there's a simplicity to it as well.

It does reference 100 Broken Windows and The Remote Part, but also references Interview Music and other records that we've made. It's got a little bit of everything, actually – maybe not the teenage Hope Is Important vibe, but then that would be a bit inappropriate, if lots of men in their late 40s were trying to be 18. I think it's a really good record.

We put our shows on sale before we'd announced the record, because we were approaching it with caution, thinking how there's so many bands out there trying to sell tickets. We'd no idea if we'd be able to sell out. But some of the shows sold out so quickly and there seemed to be a real anticipation again. It feels similar to when we announced Everything Ever Written – it's been a six year break between albums, and we've hardly played shows at all. So it really feels that people are quite excited about seeing us play again – as are we to play gigs and actually put a record out.

Idlewild's new album, Idlewild, will be released on October 3 via V2 Records.

Briony is the Editor in Chief of Louder and is in charge of sorting out who and what you see covered on the site. She started working with Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Prog magazines back in 2015 and has been writing about music and entertainment in many guises since 2009. Her favourite-ever interviewee is either Billy Corgan or Kim Deal. She is a big fan of cats, Husker Du and pizza.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.