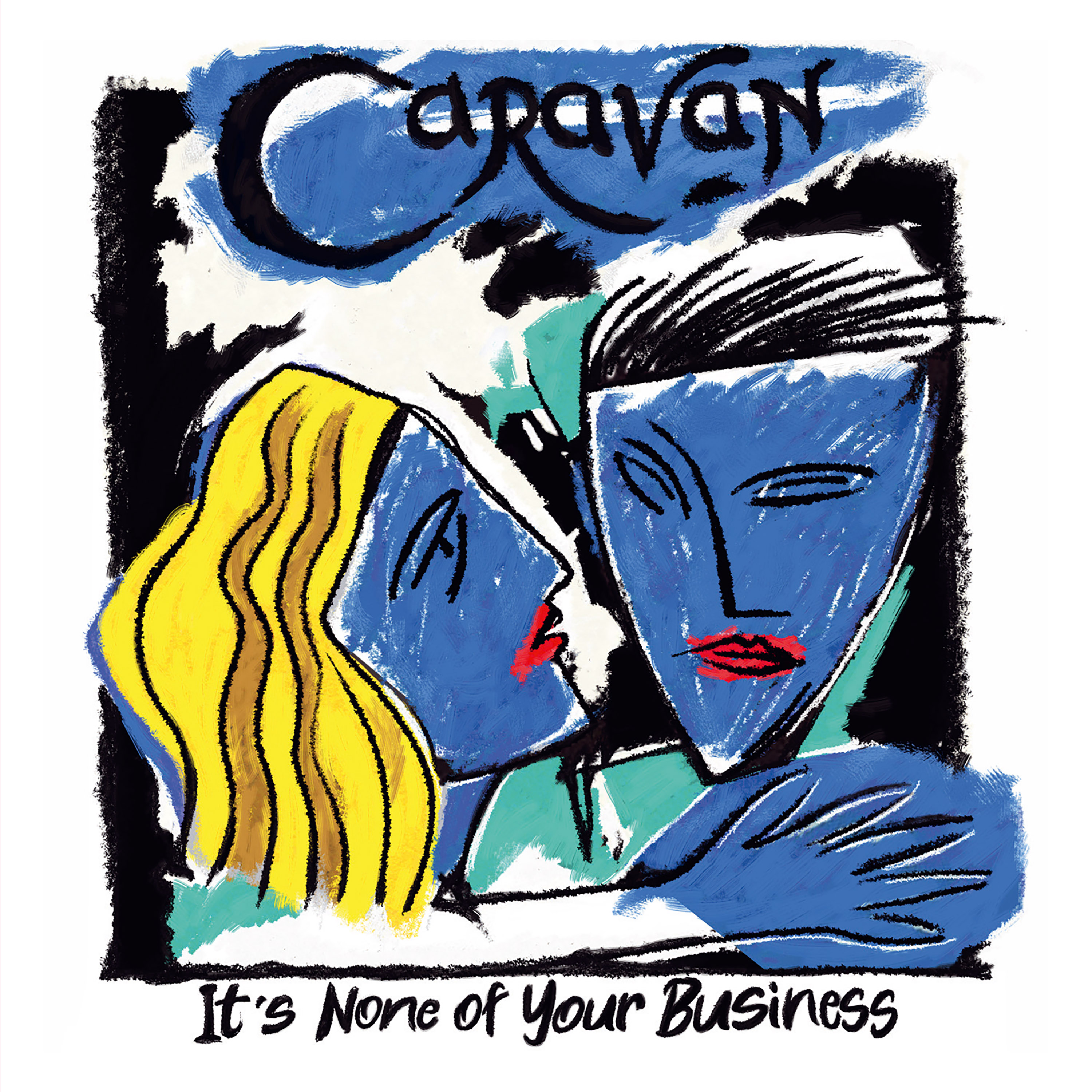

"It was the way to go in the early days, doing longer and longer tracks. To revisit that is a good experience." The story of Caravan's It's None Of Your Business

In 2021 a refreshed and reinvigorated Caravan released their finest album for years. This is the story...

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“I brought It’s None Of Your Business to the band and they said, ‘Great, a long number at long last!’” says Caravan guitarist and vocalist Pye Hastings about their new album’s title track, which clocks in at nearly 10 minutes. “But it came out really well. It was the way to go in the early days, doing longer and longer tracks. To revisit that is a good experience. It works now as it used to work then.”

“We rehearsed it and played it in real time as a long piece and enjoyed it,” says viola player and guitarist Geoffrey Richardson. “We were comparing it to Nine Feet Underground [from In The Land Of Grey And Pink], but that was edited together.”

On It’s None Of Your Business Caravan sound reinvigorated. The two long songs (I’ll Reach Out For You clocks in at over eight minutes) both nod back to their 70s heyday, while the shorter tracks have more vigour and energy than those on 2013’s Paradise Filter. But just before the recording sessions, bassist Jim Leverton quit. “He left because he is more of an R&B player and says he doesn’t like prog anymore,” says Hastings. “He wanted to do his own thing.”

Article continues belowAnd then there were four. But rather than Leverton’s sudden departure derailing the project, it brought the band together. Hastings, Richardson, keyboard player Jan Schelhaas and drummer Mark Walker went into Mike Thorne’s Rimshot Studios near Sittingbourne in Kent, with Pye’s son Julian producing, sat in the round in the main room and recorded the backing tracks live. “We wanted to do it the old-fashioned way,” says Hastings. “I think it comes out in the music that the band was having a good time. It was a bit fast in places, but there was a spark to it and I like that.”

Caravan needed a bassist pretty quickly and drafted in Mark Walker’s good friend and super-sessioner Lee Pomeroy, who has played with It Bites, Headspace, Rick Wakeman and ELO. He recorded some of music with the band, but most of his bass guitar was overdubbed.

“It’s brought the whole thing alive,” says Hastings. “He did it so bloody quick it’s unbelievable – he got the whole thing done in two days. It’s like Richard Sinclair’s bass playing but with a more modern feel; it works really well.” Although Richardson’s compared Pomeroy’s approach to another Caravan bass alumnus, John Perry, he also points out that he brings something else to the band as well. “Lee is superb, I love him,” he says. “He’s absolutely added a new dimension to the group.”

“I’m a fan,” says Pomeroy. “I don’t know their entire catalogue but I know some of the old classics like In The Land Of Grey And Pink. When we recorded the album, the weather was gorgeous and we’d stand outside in the sun when we took a break. That’s how to record!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Pomeroy also plays fretless bass on a couple of tracks. “I’d been listening a lot to the late, great John McKenzie, who sadly passed away this year, bless him,” he explains. “His fretless bass playing with Steve Hillage was so brilliant and that inspired me to take the fretless along to the session.”

Hastings says that he always writes the music first and adds lyrics later. He admits that this can be very easy, or the lyrics might take weeks and he might still be writing the words in the studio. But an unexpected benefit of the recent Covid lockdowns was that they sharpened up his songwriting process.

“I’ve got my guitar, wine, a nice house, the sun was shining, what else am I going to bloody well do? The songs poured out. It was great.”

But some of them are very serious. Hastings sings about those who didn’t make it through the pandemic on the touching Spare A Thought, while criticising the selfishness of “the people who deny” – the anti-maskers and the conspiracy theorists.

“I was thinking about the nurses who work all hours,” he explains. “I felt quite strongly about it. It’s a fantastic thing that we’ve got the NHS and they should be paid a lot more than they are. I wrote a song that highlights the whole thing.”

It feels like he’s taking stock and reflecting on what really matters in life on the tender love song There Is You, and particularly on Every Precious Little Thing. “It’s the small things in life that mean the most: love, things that spark off a memory. It’s extremely important.”

And in among the muscular Down From London is If I Was To Fly, a charming, albeit lightweight, ditty. It’s not particularly representative of the album and rather an odd choice for a single.

“In 1970 we played in Rotterdam with The Byrds, Soft Machine, Pink Floyd, Santana and in the middle of it were Mungo Jerry,” Hastings recalls. “It’d been raining and the sun came out when they came on stage and played In The Summertime. The crowd erupted – I’ve never seen anything like it. I thought I’d like to do one of those songs at some point and I explained to the band, ‘think “jug band” when you’re playing it’, and they got it first take. It’s a light-hearted number, I agree, but it’s good fun to play, a bit of a laugh. It’s not a serious attempt to say ‘This is Caravan’, but it’s part of Caravan.”

The presence of Pye’s elder brother Jimmy Hastings links the album back to the veryy soul of Caravan. He adds his characteristic melodic, finely poised flute lines on three of the songs and at the age of 83 his playing is as impressive as ever.

“He is a fantastic musician, the first-take genius,” says Hastings. “You play him the song once and he’s got it immediately, and he says, ‘record now’. And you think, ‘Where the hell did that come from?’” he laughs. “It’s quite extraordinary. It suits my songs, that’s for sure. It could be a family thing, an affinity.”

Speaking of which, does Pye get on well with Julian in the studio? “Yeah. We have arguments, father and son. He thinks he knows best and I say I know best. It’s a natural process and the end of the result is a good compromise. But playing in a band you have to compromise; if you just dictated it becomes a one-man thing. I’ll give [the band] the direction, but I want them to put their personality and style into it.”

Schelhaas uses a rich palette of keyboard sounds and styles, from jazzy piano to swirling organ lines reminiscent of Al Kooper on mid-60s Bob Dylan, to an extravagant synth solo on the title track. “I said, ‘Go mad on it, do what you like,’” says Hastings. “And when he’d recorded it I thought, ‘Oh, he has gone mad!’”

Richardson’s compositional contribution is the exquisite viola-led instrumental Luna’s Tuna, which closes the album. And on Hastings’ songs he plays some speedy, exciting guitar work. “Christ, it’s good!” Hastings exclaims.

“I’ve been focusing quite a lot on the guitar in the studio,” Richardson explains. “I built myself a guitar just before lockdown, a Strat, from the best pieces that I found on eBay, and I’ve been very chuffed with it. It’s a work in progress, lead guitar. I think of the cellist Pablo Casals who, when he was in his 90s, did hours of exercises, scales and arpeggios every day. A journalist asked him why he continued to put himself through this and his answer was, ‘Because I think I am making progress.’ I’m going to practise loud shredding guitar into my 90s if I can,” he says laughing. “And I also think I’m making progress.”

This article originally appeared in issue 125 of Prog Magazine.

Mike Barnes is the author of Captain Beefheart - The Biography (Omnibus Press, 2011) and A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s (2020). He was a regular contributor to Select magazine and his work regularly appears in Prog, Mojo and Wire. He also plays the drums.