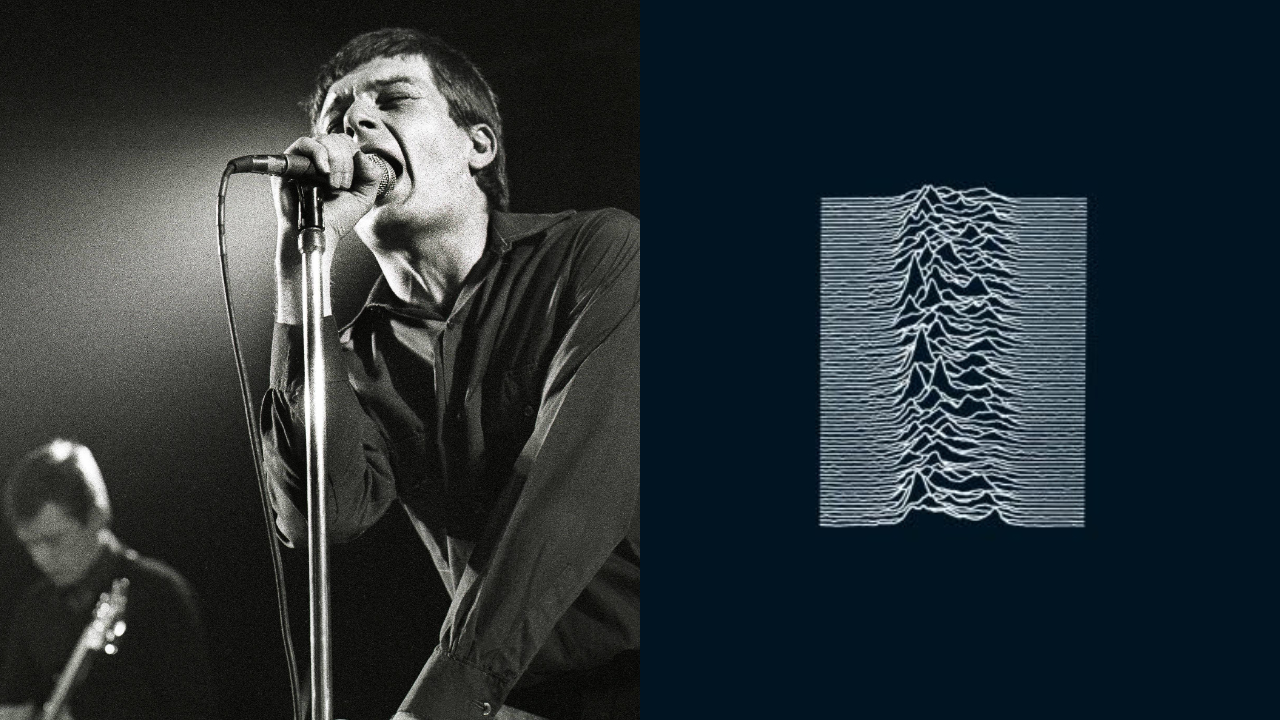

“We don't want people to know what we think”: Why Joy Division's Unknown Pleasures may be the most important record to emerge from the UK punk scene

Released on June 15, 1979, Joy Division's bleak, beautiful masterpiece has lost none of its power or stark dread

In 2018 former Black Flag frontman Henry Rollins was interviewed on the Youtube channel The Sound of Vinyl, whilst holding a copy of Joy Division's debut album Unknown Pleasures.

“When they finally write the real book on rock and roll,” he said, “when all the dust settles and the truth is finally told, when they get it right, one of the bands at the top of the mountain, along with all your David Bowies and Rolling Stones will be Joy Division.”

No one could have predicted it at the time, and it took a cast of some of music's most unusual characters, plenty of butting of heads, a truly unique group chemistry and no small amount of tragedy to get them there, but although it may have sold a fraction compared to iconic albums by Bowie or the Stones, Unknown Pleasures fully merits that glowing testimonial.

Formed originally as Warsaw, after the David Bowie song Warszawa from the album Low, Joy Division were initially just another Northern punk rock band willed into existence after school friends Bernard Sumner (then known as Bernard Albrecht) and Peter Hook attended the Sex Pistols' infamous gig at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall on June 4, 1976.

It was the guitarist and bassist's decision to recruit a young man they knew named Ian Curtis on vocals that would prove to be the making of Joy Division. Curtis was asked to join the band without having to audition: Sumner has since claimed that they let him in just because they liked him, despite only knowing him as a bloke with a jacket that had the word 'Hate' emblazoned across it.

Curtis grew up in a working-class family in Macclesfield and was a gifted child, receiving a scholarship at the Macclesfield Independent School at the age of 11. There he discovered a flair for language, and began to write poetry, having discovered the free verse stylings of British poet Thom Gunn as well as Phillip Larkin and Elizabeth Jennings. By the age of 16 he had already won numerous awards in recognition of his work, but had grown tired of the education system, instead discovering and obsessing over David Bowie and Jim Morrison. Indeed he turned his back on further education and instead decided take a job in the employment sector of the Civil Service as an Assistant Disabled Resettlement officer.

All of these things coalesced to create Curtis’ unique vocal, lyrical and performance style. In a scene of angry punk rock bawlers, Curtis’ deep, baritone croon, so full of pathos and anguish, was immediately captivating. He also suffered terribly from epilepsy, which would affect him often during or immediately after shows: the more he performed and toured with the band, the more the fits and condition worsened.

By 1977 Joy Division had been through three drummers and had found their fourth in Stephen Morris, cementing the classic line up of the band. They released a four track EP, An Ideal for Living, in 1978, which has its charms, but is barely recognisable as the band Joy Division would become just a year later.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

It was good enough, however, to get the band an invitation to make their TV debut on local news show Granada Reports from the show's presenter and local gig promoter Tony Wilson, after Curtis had berated Wilson at a gig for not having already asked them to appear. “You bastard,” Wilson recalled being told. “You put Buzzcocks and Sex Pistols and Magazine and all those others on the telly -what about us then?”

In fact, Wilson was an early enthusiast and later approached Joy Division to contribute a pair of songs for a sampler for his new record label, Factory Records. A Factory Sample featured the songs Glass and Digital, showing significant growth in the quartet's sound, with the latter going on to become one of their most beloved songs.

Initially signed to RCA, Joy Division were unhappy with their early demos for the label and requested to be released from their contract, instead signing with Factory, partially due to manager Rob Gretton’s unwillingness to travel to London for meetings. And in the spring of 1979 the group entered Strawberry Studio in Stockport to make their debut album for Wilson's label.

The album's producer was Martin Hannett, a man who already had production credits for John Cooper Clarke and Buzzcocks as well as the two Joy Division tracks on A Factory Sample. This was to prove a crucial decision; Hannett was a difficult man, but a visionary producer, and with Joy Division’s lack of studio experience Hannett had free reign to indulge in his wildest ideas. The band were, in his words, “a gift to a producer. Because they didn’t have a clue, they didn’t argue.”

So, the band who had come in to record a punk album came out with something entirely different. Sumner and Hook have both admitted since that they despised the recording of the album, indeed Hook has compared the production to Pink Floyd (although his stance has softened over the years). The bassist told the BBC: "Derek Bramwood of Strawberry Studios said that you can take a group that have got on brilliantly for 20 years, put them in a studio with Martin and within five minutes, they'll be trying to slash each other's throats...” But he also conceded “but now I can see that Martin did a good job on it ... There's no two ways about it, Martin Hannett created the Joy Division sound.”

Sumner was a little more cryptic when he added that the band had created a black and white picture, and it took Hannett to colour it in.

Hannett used a series of loops, echos and tape modulators to warp and distort the sound of the band, as well as recording the ambience from a variety of different areas in the studio including, in the basement toilet, the sound of Rob Gretton smashing bottles, and the spray of an air freshener during a drum take that nearly led to Morris passing out by the climax. Morris seemed to take the worst of Hannett’s indulgences, with the producer insisting that each individual drum be recorded separately, so that there was no bleed in the mix. Despite this Morrs says he was impressed by the various techniques Hannett employed.

When Unknown Pleasures was released on June 15, 1979, it was incomparable to anything else in the genre.

Therapy?'s Andy Cairns, one of countless musicians inspired by the record (see also Billy Corgan, The Smiths, Robert Smith, U2, Depeche Mode, Interpol, Bloc Party...) describes Unknown Pleasures as “the birth of post-punk.”

“It sounded really strange,” he says, “it was a true musical democracy. It was a gateway for me, into things like literature and Kraftwerk and dub records, it showed me that being heavy wasn’t about being tuned to A.”

That democracy was key, as each individual element of Joy Division sounds perfectly balanced and equally essential on Unknown Pleasures; the dubby bass of Peter Hook gives the album momentum and groove, Sumner's choppy and wiry guitars keep the punk and art rock aesthetic, that drum sound that Hannett so agonised over is phenomenal, Morris adding an inhuman, robotic, machine-like whirring rhythm to the songs. And then there is Ian Curtis. His voice is so filled with sorrow, melancholy and dejection, his musings on life's purpose and his own inner turmoil so genuine that they still chime with millions of disenfranchised people decades later.

It’s most apparent on what is possibly the album’s definitive song; She’s Lost Control. Inspired by a young woman who regularly came into his work while he was a Civil Servant and would regularly have an epileptic fit in the office, when she stopped coming Curtis assumed she had found a job: in actuality she had passed away. The song showed Curtis at his most empathetic and relatable, even though it was an event that obviously spoke to his own personal fears.

Not that Joy Division were keen to share what those fears might be. Asked about Curtis' lyrics, Peter Hook told NME, “[People] ask us what our lyrics are about and we say, 'Well they're whatever you hear, really'... We don't want to say anything. We don't want to influence people. We don't want people to know what we think.”

Just 10,000 copies of Unknown Pleasures were initially pressed, at a cost of £8,500: released on June 15, 1979, 5000 of those sold in the first week. But commercially the album was a slow burn. In the wake of Curtis' death in 1980, at a point when it appeared as if Joy Division were about to break through to a larger audience, the album peaked at number 71 on the UK albums chart. But this stat is irrelevant, really, for that chart position in no way reflects the importance, impact, influence and quality of what is, undeniably, a masterpiece.

From the artwork, up there with Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon or Nirvana’s Nevermind as one of rock's most iconic album sleeves, to the influence it had on the music of its hometown, from The Smiths to The Fall to The 1975, to the music itself, with that alien production, and songs as dark, unusual and moving as Disorder, the harrowing Day Of The Lords, the moody Shadowplay, the punky Interzone and the beautiful New Dawn Fades, Unknown Pleasures is a monolithic totem in popular culture.

“In many other hands Joy Division's relentless litanies would appear pompous, tasteless or just plain vicarious,” noted NME's Max Bell in his original review of the record, published in the July 14, 1979 issue of the magazine. “The Sex Pistols, for example, turned out to be all three. But Joy Division are treading a different tightrope; what carries their extraordinary music beyond despair is its quality of vindication. Without trying to baffle or overreach itself, this outfit step into a labyrinth that is rarely explored with any smidgeon of real conviction. By the time they experiment with the dialogues of schizophrenia on I Remember Nothing, they have you convinced of their credentials.'

Listened to today, 44 years on from its release, its unique power has not diminished.

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.