The sad story of White Lion, the band that was allowed to die

In the late 80s, with their live shows and second album punching hard, the rock press fighting their corner and the band gathering momentum, White Lion’s future looked bright. But it soon dimmed rapidly

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

When White Lion arrived in London in January 1988 to play their first ever European shows, the New York band seemed to have the world at their feet, and their incendiary second album, Pride, had set the rock press in a right old tizz.

“If White Lion didn’t exist we’d have to invent them,” Derek Oliver purred in his five-out-of-five review in Kerrang!, adding that Vito Bratta, the band’s guitar whizz kid, was “probably better than Eddie Van Halen himself”, and Danish-born frontman Mike Tramp was “blessed with a far better voice” than David Lee Roth.

Over the band’s three-night residency at London’s Marquee club, some claim that White Lion outperformed Guns N’ Roses, who had blown hot and cold on the same stage the previous summer.

After the European dates, Tramp, Bratta, bassist James LoMenzo and drummer Greg D’Angelo flew back to the US, where they then toured with Aerosmith, Ozzy Osbourne and AC/DC.

Thanks in a big way to the support of MTV, who got behind the singles from the album – Wait, Tell Me and the plaintive When The Children Cry – Pride went on to sell two million copies in the US alone.

And yet within five years this Lion was extinct. Stranger still, following the group’s hasty dissolution the music world heard nothing further from the extremely talented Bratta. How the ball was dropped from a position of such strength isn’t simple to explain.

Yes, like many others White Lion suffered from the rise of grunge. But what’s really astonishing is the complete lack of support they received from their record label and management – not to mention the way the self-coined ‘little fighters’ appeared to just give up, and collapse like a house of cards.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Nobody went in to bat for White Lion when we needed them most,” Tramp sighs now. “And because of that the band was allowed to die.”

It’s early 1987. Somewhere in the empty L’Amour nightclub in New York City, a phone rings incessantly during a White Lion rehearsal. Given that the band’s managers George and Michael Parente also co-own the building, most incoming calls are business-related. To this day, Mike Tramp has no idea what compelled him to jump off the stage and pick up the receiver.

“I had only done so once before, and the voice on the other end of the line was Kelv Hellrazer [of UK-based magazine Metal Forces], which led to White Lion’s first exposure in Europe,” the singer says. “The second time it happened, [producer] Michael Wagener told me that even though we didn’t have a label deal, he was taking us to his studio in Los Angeles to make a record.”

In early ’87, White Lion needed another break – and fast. Their debut album, Fight To Survive, had been recorded for Elektra Records, who shelved it but returned the rights to the band, leading to a deal with US indie label Grand Slamm. Several bassists and drummers came and went, although the band’s success in Japan was enough to nurture the faith of mainstays Tramp and Bratta.

The band then made a version of Pride which they themselves scrapped. When management heard that Atlantic A&R scout Jason Flom was headed to Florida to check out a band called Mannequin, at a show at which White Lion were the support, they sent Flom a limo with a fully stocked bar.

The move paid off. The way Tramp tells things, Flom didn’t even watch the headliners, but fell in love with White Lion and agreed to sign them – and then forgot all about it.

"It’s a true story," Tramp insists. "Back then, Jason was at a time in his life when he was drinking and taking drugs. He gets completely plastered, returns to New York and checks into rehab. When he came out, our Italian-American managers had to remind him about the offer."

Wagener had already worked with Great White, and also Dokken and Stryper, and would become one of the decade’s biggest production names. An original guitarist with German metalheads Accept, he brought a musician’s perspective to the studio.

“Michael became the fifth member of White Lion,” Tramp recalls. The air of sympatico was a bedrock element to Pride, which still sizzles with flamboyant, virtuoso musicianship and swaggering self-confidence.

“All of Vito’s guitar solos were songs in themselves,” Tramp says. “Pride was our live set at that point,” he continues, “and as those songs were laid down there were no arguments or debates, just smiles.”

In a strange coincidence, Pride was released on June 21, 1987, the same day as GN’R’s Appetite For Destruction.

“We were like two race cars lined up at the starter’s gun,” Tramp says, chuckling at the memory. “And although Guns N’ Roses eventually won the race, for a time things were neck-and-neck.”

The review in Kerrang! said Pride was “the most essential melodic hard rock purchase in years”. But progress remained slow, despite a North American tour with Ace Frehley and Y&T. Tramp admits now that “our management came close to giving up on the band”.

A chink of daylight emerged when a radio station in Minnesota started to play the album’s first single, Wait. Then a station in San Diego picked up on it. Gradually, more followed suit. With MTV it took intervention from Tramp himself to secure heavy rotation for Wait.

“The video had already been around for seven months, but now that the song was big on the radio I picked up the phone and managed to get through to somebody who agreed the situation was unfair,” he recalls. “The following week we began to climb. Why hadn’t the record company done that?”

Wait took White Lion into the US Top 10, but follow-up single Tell Me stalled at No.58. It took When The Children Cry – a politically inspired ballad with lyrics Tramp wrote after watching Live Aid – to return the group to the chart’s upper reaches (in this case No.3) and to prove that they could offer something out of the ordinary; this was a protest song in the days of hair-metal.

“I still find it hard to believe that a kid from Denmark sang about there being no more [US] presidents, and the ending of all wars,” Tramp marvels. “The truth is that I always found it difficult to write about sex or innuendo. Although I got close with a couple of my songs.”

Tramp still finds it difficult to believe that (as he discovered in recent years) Atlantic actually opposed releasing Children as a single. “Our managers had to threaten bringing all their wise-guy friends from Brooklyn to make it happen,” he jokes.

Gradually, things fell into place for White Lion. The band’s three gigs at the Marquee were sell-outs, and are rightly regarded as being on a par with early UK visits from Twisted Sister, Y&T, The Rods and Anvil.

“In London I shared a hotel room with my manager, who in the middle of the night shouted excitedly: ‘Oh my god, we got it!’ We had been confirmed for a tour with Aerosmith,” Tramp remembers. “And a week into that tour we learned that two days after it finished we would begin three months with AC/DC. I couldn’t name one single hour on those two tours that I didn’t enjoy. We had worried about booing from AC/DC’s fans, but each night twenty-five thousand Bic lighters would go up in the air.”

Going out again with Kiss, who were promoting Crazy Nights, was a little less satisfying. “We were on the worst tour Kiss ever had,” says Tramp. “But as the support band we continued to go down well, so that didn’t really affect us.”

Pin-up looks notwithstanding, White Lion had an image problem – they were just four ordinary guys. The group even summoned their publicists and lawyers for what ended up being a fruitless meeting to cook up some kind of “cool rock’n’roll” press stunt.

“While our rivals were overdosing or driving cars into swimming pools, we were like: ‘Who ate my slice of pizza?’” Tramp says, laughing. “That had a lot to do with the story of our band.” With two million US sales, Pride peaked at No.11 on the Billboard chart. White Lion could – and should – have gone on to bigger things. But Tramp admits they were “burned out” from the road.

Worse still, he and Bratta had begun drifting apart. With their label pushing them for a rapid followup, within days of coming off the road the pair found themselves at a motel in Palm Springs writing their next record. Only this time there was an added pressure – hit singles.

Atlantic strong-armed them into including a cover of Golden Earring’s 1973 hit Radar Love. That next album, Big Game, went gold in June 1989, but all four singles from it – including Radar Love – stiffed.

In those days, reviews in print could make or break a band, and Tramp still considers Kerrang!’s damning one-out-of-five assessment of Big Game – “This is the lamest, most pussy record I’ve heard in a long time” – to be as significant as the plaudits they had received for Pride.

He admits that he began to lose the plot, and recalls being backstage at Wembley Arena when White Lion were the meat in a sandwich featuring Mötley Crüe and Skid Row in November ’89.

“I told a journalist from the Melody Maker that we were more like The Beatles than those two bands,” he says, laughing. “What was I thinking?”

Their fourth album, Mane Attraction, released in 1991, was an improvement on its predecessor, but by then strong winds of change were about to start blowing in from Seattle. The writing was on the wall when Atlantic forced them to re-record the first album’s Broken Heart – and then slammed down the shutters.

“I went to see [Atlantic president] Doug Morris when nobody from Atlantic came to our show in New York,” Tramp says. “To get into the office I had to pretend I was Sebastian Bach – by then I already knew there was a new kid in town.”

At the tour’s conclusion in Boston four days later, Tramp, still reeling from the latest rejection, told Bratta: “Tonight is the final White Lion show”, and was then taken aback by the guitarist’s casual response: “Okay.”

Twenty-nine years later, Tramp is now sanguine. “In all our times together, Vito and I didn’t have a single argument,” he states. “The problem was that we were very different people, with no friendship outside of the band.White Lion could have had a future, all we needed was to take a break and regroup, get a new haircut and catch our breath.”

Tramp wasted little time in forming Freak Of Nature, intended as the band of close-knit brothers he had always wanted White Lion to be. But two albums was all they managed.

Meanwhile, Bratta dropped off the radar completely. In what little contact that followed between the two men, their relationship was tense. The guitarist was angered by the singer’s new-millennial attempt to reprise the band without him as Tramp’s White Lion.

In 2008 Tramp released the album Return Of The Pride, billed as a White Lion record but with no input from Bratta. It was too much for Vito, who, in his first interview in 15 years, revealed to broadcaster Eddie Trunk that after White Lion he’d spent half a decade helping his mother care for his terminally ill father, and after that suffered a hand injury that severely impaired his guitar playing. A decade on, the condition of his hand had improved a little, but he remained unsure how much of his ability would return.

“I’ve never said no to a White Lion reunion,” he told Trunk. “But it’s like a girlfriend that you break up with who says: ‘If you don’t get back with me, this is what I’ll keep doing.’ The more she cheats, the more you’re not going to get back with her. I have to keep watching this stuff. I wish Mike luck, but the more he does it the less I want to be a part of it.”

Relations between Tramp and Bratta (who declined to be interviewed for this story) are now better than they have been for years, although a renewal of their partnership still remains extremely unlikely.

“For Vito [the continued stonewalling] is his way of dealing with a situation that has no real solution,” the singer says.

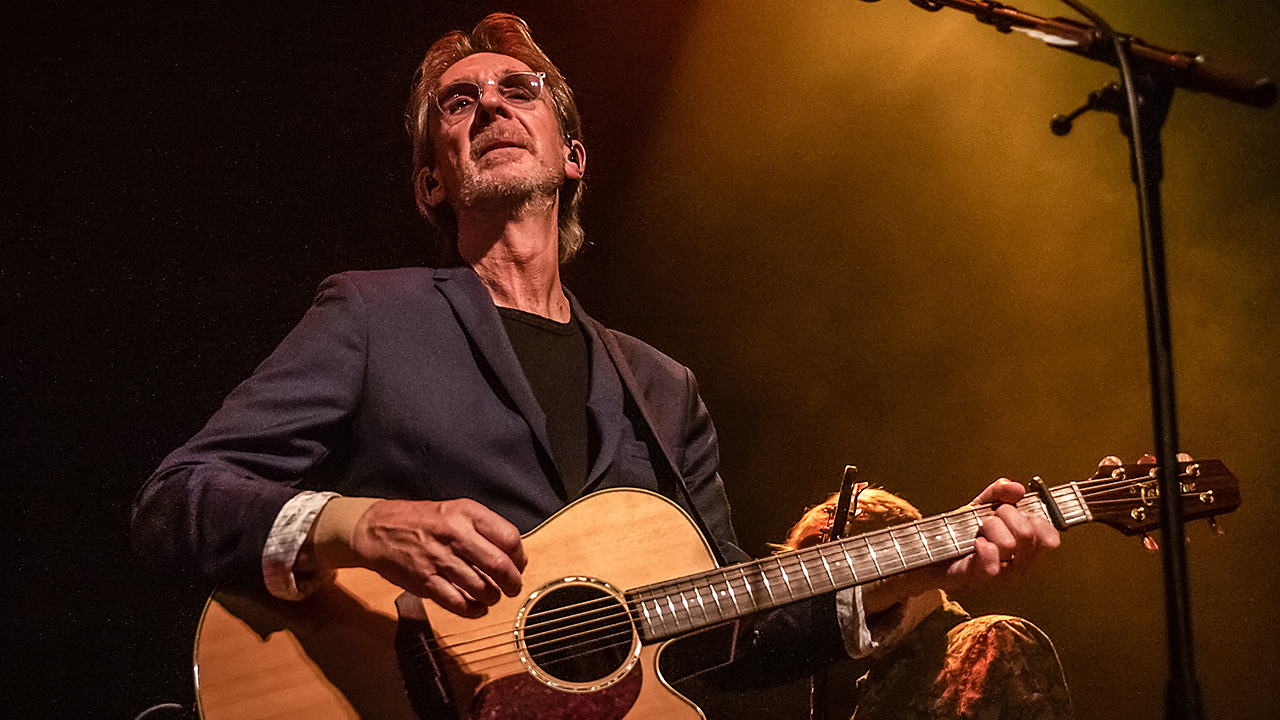

Tramp continues to record new music and tour. His twelfth and latest solo record, Second Time Around, ploughs an observational singer-songwriter furrow. A planned tour of all-White Lion material has been delayed by COVID-19.

“I turn sixty in January. It took some time, but I’m at peace with what happened. And I still love those songs – so long as I don’t have to reproduce the 1988 versions,” he explains. “Performing them the way I do now feels completely natural.”

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.