It's 1992 and Buffalo Tom are mixing Hüsker Dü and Van Morrison to make one of the decade's greatest albums

30 years on: The making of Let Me Come Over, the album that showed that alt.rock could have some heart

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

The late 80s was an odd time to start a band like Buffalo Tom. If it wasn’t Springsteen hitting his commercial apex on FM radio, then it was bands such as Poison and Ratt who were filling the airwaves, even in Buffalo Tom’s sleepy Boston suburbs. For their part, singer/guitarist Bill Janowitz, bassist Tom Maginnis and drummer Chris Colbourn were at home listening to Hüsker Dü and The Replacements, guitar bands from the alternative rock scene who still had a live sound. The very not-live sound of radio rock was, according to Janowitz, the bane of music in the mid-to-late 80s.

“Oh, man,” he groans. “I still listen to classic albums from the eighties and I love the material, but can’t stand the production. Even something like Springsteen’s Tunnel Of Love, it’s an achievement of great songwriting, but the production really holds it back.” He pauses, then says with a laugh: “Is that heresy?”

Formed in Boston in 1986, Buffalo Tom recorded two albums – 1988's Buffalo Tom and 1990's Birdbrain, both co-produced by Dinosaur Jr's J Mascis – but even fans of that early work, with great songs like Sunflower Suit, Impossible and Fortune Teller, weren't quite prepared for 1992’s irresistible Let Me Come Over. It jangled, rocked and broke hearts, bringing a warmth and optimism to the bleak post-grunge landscape.

And Boston had been delivering bands like that way before grunge: Dinosaur Jr, the Pixies, the Breeders, Throwing Muses, the Lemonheads, Blake Babies, Big Dipper and more.

“There was a voracious appetite for that kind of thing in England and Europe,” says Janowitz. “Take a band like Pixies. I was going to the see them play to fifty people in Massachusetts, their own state, before they went to the UK and became very big there. Same thing for our friends Throwing Muses and Dinosaur Jr, too.”

For Let Me Come Over, the band parted ways with Mascis and moved into the picturesque Dreamland Studios, a converted church set among the woods just outside Woodstock.

“It was very beautiful, and so inspiring,” says Janowitz, “We did three days there and we loved it, but we didn’t have the schedule or budget so we did the rest back at Fort Apache studios in Boston.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Their first two albums had promised much, but Let Me Come Over was the sound of a band taking flight. “We were very much swept up in the whole thing,” says Janowitz. “I can’t believe we got to make three records! [The band have recorded nine studio albums so far.] I had never really sung before being in Buffalo Tom, so we were all just learning. Having this chance to go out and see Dreamland and Woodstock was a lot of fun.”

Let Me Come Over was also the first time the band really flexed their songwriting muscles. Previous albums had been built on the premise that if you had ten songs going into the studio then you had ten songs on the record. Now the process was more about selection and finessing the arrangements, experimenting with keys and harmonics.

“I specifically remember bringing in Mineral and running through that with the band in rehearsal and feeling: ‘Wow, we’ve got something different.’ This was us letting our influences of a band like Hüsker Dü meld with an artist like Van Morrison. And Larry felt like that too. It didn’t feel like anything else but a Buffalo Tom song. We hadn’t experienced that before."

The new songs owed something to a rudimentary device beloved of guitarists: the capo. "I’d never used a capo before, other than just fooling around on acoustic guitar at home," Janovitz told Magnet. "It came down to something as simple as that—a way to get the juices flowing. It was like, 'Wow, I’m playing all these cowboy chords, with all this big, wide-open space. If I just move this capo up the neck, oh man, my voice goes up here and there’s all these different harmonics.' When you apply that to an electric guitar and put it through a distortion pedal, you get songs like Larry or, later, Treehouse and I’m Allowed – those are all up in the same capo position."

Bass player, co-writer and co-singer Chris Colbourn felt it too: "It definitely was a step up, especially Velvet Roof, Mineral and Porchlight. Bill got away from all the other indie-rock bands and just wrote what he wanted to write. We were big Kinks, Beatles and Stones fans. Maybe that wasn’t very cool, but [we thought] this was going to be our last album, anyway."

And while Buffalo Tom were blossoming as songwriters, their producers at Fort Apache, Paul Q Kolderie and Sean Slade, were waiting for technology to catch up to the production vision they shared, utilising automated mixing – something of a rarity.

“We got the rough mixes, and [label] Beggars Banquet liked the material but they wanted it to go to a remix guy. I talked to Ron Saint Germain [Michael Jackson, U2, Living Colour], who was a hotshot mixing guy, on the phone. He was a character. He was like: ‘I’ll save your little record! I’ll come up on my private jet and get it done.’

"We got his mixes back and we were blown away – mostly in a good way, but some bad. We had him tone down some of the stadium rock, but he was a good sport and did a great job with it.”

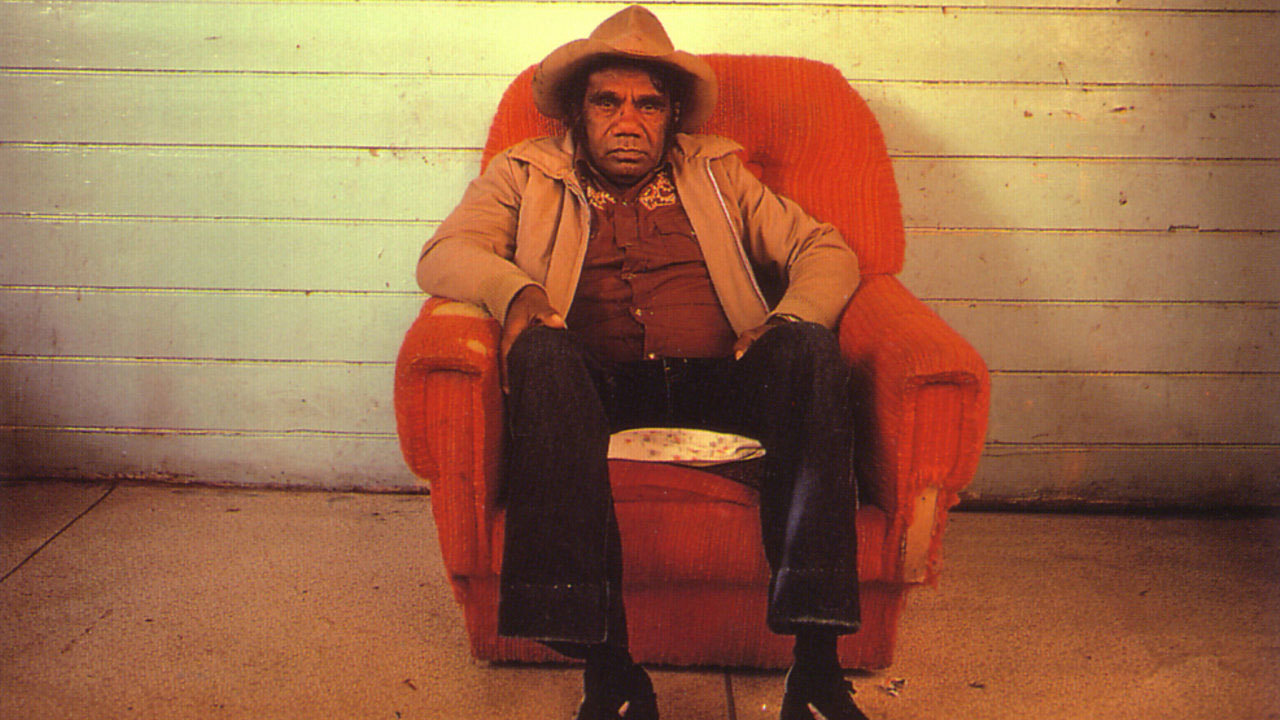

Released on 10 March, 1992, in a sleeve featuring a picture of an Australian Aborigine chief they had seen in National Geographic, Let Me Come Over took everyone by surprise. "There was some criticism about suburban white guys exploiting the black experience," drummer Tom McGinnis told Magnet, "and it sort of put people off-kilter as far as, 'Does it really represent the music?' But we liked that, in a twisted way."

A critical and commercial success, Let Me Come Over landed in a post-Nevermind landscape. “That record really did change our world,” says Janowitz. “It coincided with [the influence of] people we’d grown up with – college radio, DJ guys we knew who went on to MTV or to promote gigs. The lunatics did take over the asylum, so that bands like us were considered capable of mainstream hits.”

But what of the song that would come to typify Buffalo Tom; the anthem for disaffected teens that no Buffalo Tom show would be complete without – the elegiac Taillights Fade?

“Later on I felt that it was one of my first really crafted songs,” says Janowitz, “but I never thought of it as a stand-out single. It was pretty dark and depressing. It’s basically about being resigned, giving up, feeling older than your years, feeling apart and alienated. And being on tour was in, and of, itself a manic experience, and that cultivated that uncertainty.

“I mean, I like the song a lot, it means a lot to me,” he continues. “I’m glad to have any song, even if it was just that one, that meant something to somebody, and the fact that it meant a great deal to a lot of people. It’s obviously a well-crafted song and I’m proud to do it and I enjoy playing it.

“You asked if it’s like our Free Bird – something we always have to do,” Janowitz says with a laugh. “But you have to remember Free Bird is thirteen minutes long, and Taillights is just three and a half.”

Let Me Come Over is available on Amazon and all good streaming services. For news on Buffalo Tom, visit their website.

Philip Wilding is a novelist, journalist, scriptwriter, biographer and radio producer. As a young journalist he criss-crossed most of the United States with bands like Motley Crue, Kiss and Poison (think the Almost Famous movie but with more hairspray). More latterly, he’s sat down to chat with bands like the slightly more erudite Manic Street Preachers, Afghan Whigs, Rush and Marillion.