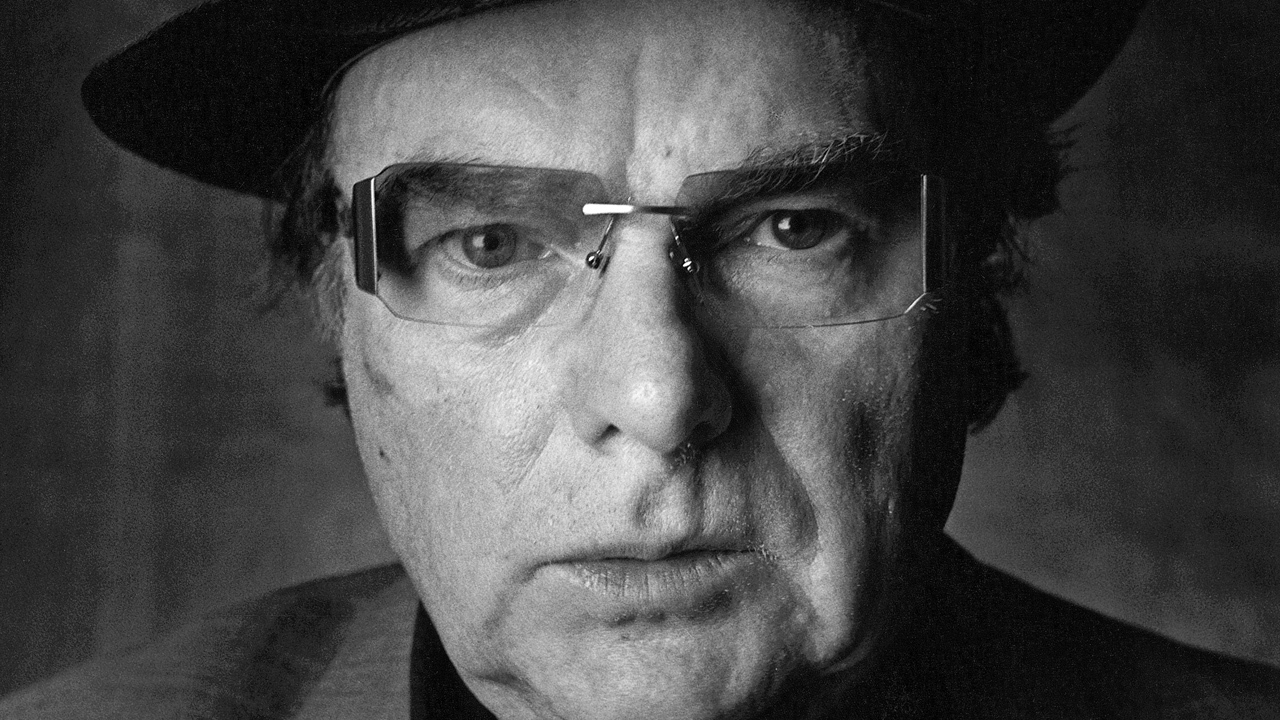

Van Morrison: Dark Knight Of The Soul

Van Morrison has lived an extraordinary life. Here, Van The Man looks back on it all with typical candour...

The Portobello Hotel, the venue chosen by Van Morrison to tell his story of the blues on a clear, late September afternoon, lies a short walk from Notting Hill Gate. A lot has changed in this West London neighbourhood since Morrison first came to the area from his native Belfast in the mid-60s.

Much has changed for Sir George Ivan Morrison too – the knighthood bestowed in this year’s honours list merely the latest of several belated symbols of prestige. An honorary doctorate, Grammy and Songwriter awards, a star on the Hollywood Walk Of Fame, a place on Obama’s playlist, a picture with Lady Gaga – all bear witness to a pre-eminent, world-shaking talent bred in the humble backstreets of post- war, working class east Belfast.

And yet, regardless of the wealth and material rewards his talent, tenacity and hard work have brought him, Morrison has remained forever bound to his early roots, both in song and in actuality. Just like the blues that first brought him there, Notting Hill and its surrounding area have been recurring staging posts in Morrison’s musical journey.

First mentioned in Them’s Friday’s Child and then in the torrid, end-of-his-tether, Bert Berns-produced solo recording He Ain’t Give You None, ‘The Gate’ and nearby Ladbroke Grove featured alongside his home city in the shifting cinematic scenarios of transitional, landmark 1968 album Astral Weeks. That album may have signalled a farewell to the haunts of youth but it seems that Morrison will never be done revisiting them.

After spending most of the 70s forging his reputation in the States, he could often be seen in the Notting Hill Gate area when he relocated to live in England and Ireland in the 80s. Often to be seen in local coffee shops, the wanderer returned to his home from home. In an onstage improvisation of the period he sang of ‘sitting down in the mystic church, in the Notting Hill Gate’. He last performed his latter-day revamp of Astral Weeks live in its entirety at the nearby Albert Hall in April 2009. That evening Morrison took some time to emphasise the connection between the album and his current location. Setting up the record’s senses-stalling blues tragedy Madame George, he offered a few words of explanation to the audience by way of introduction.

“The next song takes place in several locations, one of them near here. The protagonist…” As he spoke, an appreciative gathering hubbub from the crowd threatened to drown out his voice. So he raised it. “The protagonist,” he continued, “is given something to smoke – that contains opium. This explains what happens later.”

Thus Madame George was pulled back from the gentrified, £100-a-ticket setting, the polite murmur and the chatter, and restored to its rightful, transcendent, opiated, vernacular home on high.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In the years before and since, Morrison’s recordings and live performances have offered many examples of such a steadfast, determined attitude that has kept him true to his calling. Through Belfast and Boston, from Woodstock to San Francisco, through the £250 hotel gigs with dinner and the days of wine and roses.

Always taking time to pay tribute to his sources, Morrison has simultaneously celebrated and, through his own compositional and improvisational genius, extended the blues form. His endlessly autobiographical lyrics contain the names of early but eternal musical inspirations. Muddy Waters, Lead Belly, Ray Charles, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Gene Chandler, Mahalia Jackson and more ring out, touchstones and talismans on a tireless journey.

In his time Morrison has been a disciple and pilgrim, trailblazing originator and wandering exile – not just from his homeland but also from the machinations of fame, the record industry, even the material world itself.

Now, in his eighth decade, he stands as a blues champion and ambassador, a living repository of knowledge about the music he has spent a lifetime learning and listening to, often playing with the very musicians (Bobby Bland, John Lee Hooker, Lonnie Donegan, BB King, Ray Charles) that inspired him in the first place. However, as numerous of his songs have made clear, following and staying true to the blues has never been an easy path.

Shortly after he arrives in the Portobello Hotel drawing room, Morrison asks for the background music to be turned off, then orders leaf tea and a bacon, lettuce and tomato sandwich. He chooses a seat at the table by the window, nearer the light, almost in the garden.

Soon he’s recalling the first performers he ever saw live on stage while growing up in Belfast. There was the Jimmy Compton Jazz Band at his Orangefield secondary school, and Emile Ford And The Checkmates at The Kings Hall. At the Plaza Ballroom there was Screaming Lord Sutch (he of the Monster Raving Loony Party, mentioned in Whatever Happened To PJ Proby?) and local hero Brian Rossi (later of The Wheels – he’s the ‘shaved head at the organ’ on the title track of Hard Nose The Highway).

Around this time, Morrison and childhood pals were starting to play together in a series of bands. “Just starting – myself, George Jones, Bill McAllen, Roy Kane, a guy called Wesley Black…” But although he’d already been privileged to hear and fall in love with the seminal blues recordings collected by his father, actually playing blues seemed nigh-on impossible.

People just thought you were a nutcase if you wanted to play blues, y’know?

“Let’s forget about the mythology here, because there’s a lot of mythology flying around about this…” he insists, firmly. “At the time basically it was very difficult for anyone to play blues, y’know? It was kind of taboo, even the subject. To actually say, ‘Well, you know, I want to do this for real,’ it was a bit scary. Now all that has been reinvented, like everyone was doing it. Everybody wasn’t doing it.”

So why was it taboo? “Because it didn’t register.” Was racial prejudice a factor? “Nah, nah it just didn’t register as something people could do. Everyone was doing copies of Top 20 hits or whatever. It just didn’t… people just thought, you’re never going to do that, ‘You’re not going to be able to achieve this.’ They just thought you were a nutcase if you wanted to play blues, y’know?

“So I know history is being reinvented. It looks like, with a lot of these TV programmes and stuff that’s coming out, that everyone was doing it. They weren’t because, well, when I was doing it… just forget about it, it’s never going to happen. In fact, some of the people that I was starting to rehearse with actually got cold feet and started to jump ship before it ever got to the starting gate. It was quite different in those days. People didn’t think they could achieve playing blues then, especially in Belfast. It might have been different in London but in provincial areas it was taboo.”

So what gave him the determination to follow through and make good on his musical ambition? “Because I’d been hearing it all my life and then started playing it – in skiffle groups originally, and listening to the recordings – my father had the recordings. So I was practising, listening to recordings from when I was 12 or 13 or something.”

A few weeks before our meeting at The Portobello, Morrison was back very close to where this musical journey began, celebrating his 70th birthday with two shows on Cyprus Avenue in Belfast. A short walk but a social world away from the terrace house on Hyndford Street where he was raised, the tree-lined avenue’s grand houses represent a much loftier milieu to the one inhabited by the young George Ivan.

He says that although it was referenced in his rendition of On Hyndford Street and alluded to on The Healing Has Begun, he had never intended to play Cyprus Avenue at either show. This seemed significant – it was in Hyndford Street, after all, where his father and friends played the music on the family record player that would guide his future. “Basically Lead Belly and Josh White and Sonny and Brownie. Mainly Lead Belly and Sonny and Brownie.”

Why was Lead Belly in particular such a potent influence? “Well, it’s very difficult to put this in words. I don’t know, y’know? It just had a kind of resonance; it affected me in a way I can’t really put in words.” Were there particular songs of his that made an impact? “Basically, all of them. Like Take This Hammer, Ella Speed, Goodnight Irene, Stewball, Alabama Bound basically anything. There was a lot of variety in there.

“Also, there was a guy on TV when I was a kid called Rory McEwen doing Lead Belly and also other blues stuff, throwing it in, original songs in-between folk songs. A guy called Cliff Michelmore had the programme where Rory was doing that. That was pre-Donegan, pre-Rock Island Line explosion, I think, because obviously Donegan was playing it with Ken Colyer and all those guys before that.

“At the same time I was listening to Lead Belly I was also listening to Jimmie Rodgers – ‘the singing brakeman’ they called him – and Hank Williams. So it was all kind of going on at once.”

Jimmie Rodgers’ style was possibly the most perfectly self- contained art form in music, ever.

“Yeah, that’s right, that’s right…”

What’s your favourite songs of his?

“Well, I actually got it loaned to me, a friend loaned it. My favourite track was T For Texas, T For Tennessee, T For Thelma, Blue Yodel Number 9 I think it was called. One of those blue yodels. Mule Skinner Blues was the same thing – everything he did was great.”

Morrison’s father’s record collection, the TV and even radio (particularly the Voice Of America jazz broadcasts alluded to on Wavelength) were sources for discovery. But Morrison doesn’t think Belfast’s oft-remarked-on status as a major port was particularly relevant in making the music he loved available.

“I don’t really get that,” he says. “There was a guy called Solly Lipsitz and he had a record shop called, believe it or not, Atlantic Records – before the ‘other’ Atlantic Records. This was in the high street in Belfast and my father used to go there. He got all his records at Solly’s place, and took me there when I was very young. He had the records and he wasn’t a sailor [grins], so, no – I don’t get that one.”

Morrison still retains most of his late father’s old collection of 78s, but tells us: “Unfortunately I don’t have time to listen to them, y’know?”

There’s another idea, partially fostered by the romantic and transcendent visions of Morrison’s own songs, that the pre-Troubles Belfast of his childhood and youth presented a mystic idyll, an Eden before the fall. This is another myth he’s keen to dispel.

“Was it idyllic? I don’t know, I’d have to ask some of the people I knew as a kid who are still around if they thought it was idyllic. I didn’t think it was idyllic from the point of view of getting a job or school or things like this. I think I was romanticising it. Some guy says to me, ‘I saw Cyprus Avenue – it’s nothing, it’s nothing.’ He was from Europe somewhere and I said, ‘Do you actually think I’m writing about the real Cyprus Avenue?’ And then he got it.

“They used to call it poetic licence – what happened to that? Everybody forgets this stuff. Occasionally I remember this. It’s not the real place and no song is, y’know, that kinda specific. You have an idea, an idea about something, and maybe the stuff I was writing later on idealised the situation. But in reality, I don’t think it was idyllic – it was pretty hard at that time. Apart from the music, other things were going on too.

“People were pretty basic and they didn’t take any shit – that’s the kind of environment I grew up in. But that didn’t have anything to do with how I described my childhood later on – in the poems or the songs. It was totally different. It was a pretty in-your-face kind of world. You could get whacked pretty easily, y’know? Punched for nothing. This was all going on at the same time.”

The meaning of the blues, from a very existential viewpoint, is that this is something you have to do – there was no choice.

Studies at Orangefield – his old school where he played two concerts prior to its closure in 2014 and which gave him the title for a standout track on 1989’s Avalon Sunset – held little interest for him.

“I was learning more on my own, reading outside of school. I don’t think they knew what they were doing really. It turns out later on that a lot of those guys in that school really didn’t know what they were doing. It was kind of like, ‘Hey you, want a job as a teacher?’ We found that out in retrospect. At the time you just thought it was weird. Later on you found out why it was weird. At the time you just think, ‘I’m not really learning much here.’”

Poets and authors feature heavily in Morrison’s songs, and Mezz Mezzrow’s Really The Blues was a key text in outlining his future course.

“It was hearing the music as well. My father had recordings of Mezzrow with Sidney Bechet so I was listening to the music as well, 78s of course, when I was reading that book. The guy was talking about how he loved the music.

“Basically, the message was ‘you do this because you love it’, y’know? That’s the only reason you’re doing it. The meaning of the blues, from a very existential viewpoint. This is something that you have to do – there was no choice.”

And it’s proved a hard love to have over a lifetime? “Yeah, exactly. Yeah yeah, that’s it.”

But you had no other choice?

“That’s it.”

Did any particular part of the book stick with you?

“There’s a part where he had a nervous breakdown. He’s just walking about and he sees kids playing in the street, and all that kind of gives him some kind of second chance after he had this breakdown. So, y’know, it’s like some kind of quote from the Bible – I can’t remember it but that’s a part that sticks.

“I was reading Kerouac at the same time, and this guy and Kerouac and the beat poets were writing in this kind of language. It was more the language, and the rhythm of the language, than what the story was, and the fact this was like some sort of connection with that rhythmic thing in language as well as in music. It’s hard to explain but I found a similarity with Kerouac, who listened to jazz when he was writing. He was constantly listening to jazz, so he was picking up the rhythm when he was writing.”

Jokingly, he recently described his father and his fellow blues-listening associates as being more “like Communists” than beatniks or hippies. Post-war Northern Ireland may not have had the Troubles (which commenced around the time Astral Weeks was released) but it surely contained the same societal restrictions the blues pushed against.

Was part of the taboo connected to playing – rather than simply listening to – the blues to do with it being regarded as a rebellious form?

“Not really,” he says. “It was just seen as like, why do you want to do this? It’s not going to make money, it’s not going to catch on. Why do you want to do it? You must be nuts wanting to do it. “Maybe it was rebellious, wanting to do it, but I never thought of it that way. I just thought, ‘This is the music I love and I want to do it.’ I wanted to do that more than I wanted to be in a showband or a rock’n’roll band. Then it began to get more poppy, so, well… maybe it was rebelling.”

Rebelling against pop music?

“You might have something there. I think it was definitely rebelling against the pop music of the day… that was a part of it.”

There was no ready-made Belfast blues scene for Morrison to gravitate to playing in. Instead, he and the aforementioned pals found their outlet via the showband scene. “If you’re a professional musician, that’s what you did. You just did whatever you had to do to be professional.”

At this point in the interview, tea, water and a sandwich arrive. There’s no leaf tea. Morrison is unconcerned: ordinary tea will do just fine, he tells the waiter. “So,” he continues, returning to the matter in hand, “if you were a professional musician you just had to take whatever work you could get basically, y’know?”

Was that restrictive?

“Nah, nah, it wasn’t restrictive. It was basically copying other things and it wasn’t the same as trying to express yourself with something like the blues, which is coming from somewhere completely different, y’know?”

Certainly. And playing the blues is one thing, but playing your very own blues, that’s something else entirely again. When was it that you started thinking you could add to this form with your own material?

“Well, it didn’t all happen at once. That’s another part of the mythology – you were here and then suddenly you were there. It was a gradual kinda thing so I guess I started my own blues about pre- the first Them album, whenever that was, about a year or two before that. So by the time I got to that first album I had got maybe four or five songs that were blues-oriented.”

Inspired by the rhythmic mouth harp of Sonny Terry, the saxophone playing heard on records by the Bill Black Combo, numerous rock’n’roll hits and The Jimmy Giuffre Trio (who were seen onscreen by Morrison at a local Picturehouse screening of 1959’s Newport Jazz Festival documentary Jazz On A Summer’s Day), Morrison’s musical skills grew exponentially. Preparation for his future was being made, though it may seem surprising that the man who would become renowned as one of the greatest singers of his generation – right up there, in fact, with the very best in recorded history – was initially reluctant to go centre stage.

“I didn’t really want to sing that much because I didn’t really want to be out front,” he explains. “So there was another guy that was out front. I was part of the horn section, playing 50 times more than I’m playing now. So I didn’t really want to be an out-front singer until I wanted to get the blues thing together. That’s when I stepped out the front, because I knew how to do it – nobody else knew how to do it.”

Perhaps the reticence is not so surprising and is in keeping with the character – an outsider/ lone bluesman perspective and persona – that burns at the heart of Lit Up Inside, 2014’s career-spanning Selected Lyrics collection, published by Faber & Faber. The young Van, not yet ‘The Man’ , heard it all and soaked it all up – folk, gospel, jazz, rock’n’roll and classical.

“I can’t believe I put that in,” he laughed on stage in Cyprus Avenue after delivering the ‘Debussy on the Third Programme, early morning when contemplation was best’ line in On Hyndford Street. But it was always the blues – the blues as a music, the blues as a calling and the blues as a way of transmuting and understanding human experience – that hooked him and, to a large extent, still defines him. The blues is always there somewhere – real and potent – in every performance Morrison gives and on every record he’s ever made. Often it means the darkness presented alongside the light – for every happy, sunny, skipping Brown Eyed Girl a wracked troubled and tormented TB Sheets. Lucifer in human form, cast out of paradise, appears in the centre of High Summer and alongside the sweet song of optimism that is the title track on 1995’s Days Like This, the deeply revealing candour of the soul-baring Underlying Depression.

Alongside the blues, Morrison has referenced and investigated poetic, esoteric, religious and spiritual disciplines throughout the course of his journey. But the man who once sang (alongside Cliff Richard, no less) of Jesus healing the sick and the lame and included a dedication to Scientology founder L Ron Hubbard on the sleeve for Inarticulate Speech Of The Heart recently declared that, these days, he wouldn’t touch religion “with a bargepole”.

But Whenever God Shines His Light still features in the set and when Summertime In England gets an airing, the voice of Mahalia Jackson still comes through the ether. Does he define any difference between the blues and gospel?

“Same thing,” Morrison says. “It’s a mixture. Like with Sam Cooke, he was combining blues and gospel – gospel secular. He was changing the situation. It was just a unique combination. Soul came from gospel.

“There’s a quote from Ray Charles about Sam Cooke where he says, ‘This is soul, Sam Cooke is soul.’ Ray Charles came from that too. It all comes from the same source… obviously blues came out of gospel. It comes from the old church, going way back to here, England; it comes back to here. The blues is the secular version. When Sam Cooke was writing about a woman instead of Jesus, just changing the words. Blues came out of that particular musical form – they changed the words and started to put different chords in it. I don’t know when it became 12 bars. I think it was probably Jelly Roll Morton that invented the form of the 12-bar blues rather than WC Handy because I think… didn’t he steal it?”

Jimmy Witherspoon blew my mind apart. He has gotta be one of the best singers that ever existed – his timing, his phrasing, everything.

In keeping with the themes explored on the still officially unreleased Caledonia Soul Music and the mighty Listen To The Lion on 1972’s St Dominic’s Preview, Morrison has previously mused on the theory of the blues hailing from Ireland or Scotland.

“It probably did,” he says. “A lot of people are saying that, but it developed into something else. There’s nothing like the Chicago blues, nothing like that. Mississippi and Chicago Blues are something different, obviously – the black people created something different with it, a unique art form.

“It still is [unique],” he continues. “There’s been nothing to match the Chicago blues that came out of Chess, there was nothing that could come anywhere near it.”

Before Them formed and their Maritime residency set Morrison on course for international fame and the shaping of his own Celtic soul-based blues tradition, he travelled with showbands. Stints in Scotland, London and playing American air force bases in Germany would make stepping up to the front of the bandstand an inevitability for the teenager. Encountering skiffle revolutionary Lonnie Donegan also opened him to new possibilities.

“It’s just that his whole thing was so different. I knew who Lead Belly was, but Donegan put his own stamp on it. He wasn’t trying to copy Lead Belly, he was doing something different with it. It was a window, yeah, definitely.”

Morrison would eventually record and tour together with Donegan but that was some way off.

“I didn’t meet him until the 80s,” he says. “Our paths didn’t cross, even though he was living not far from where I was living in California, but I didn’t really know at the time. He opened up some gigs of mine in the 80s and sat in with me and then we did the recording.

“He evolved, you see – he didn’t just stay there. Nobody stays the same. He was actually still evolving, that’s the thing never written about. Also, I never understood why there wasn’t more made of Donegan, especially in the UK. Because he was still a great singer. He still played the blues great, he played great blues guitar, and yet people seemed to be ignoring him. I never got that.”

I started the blues scene in Belfast – there wasn’t any before that.

When John Lennon returned from Hamburg with The Beatles, he told art college friends back in Liverpool that everything was different. Playing in Heidelberg with The Monarchs, then Frankfurt and Cologne with The Manhattan Showband, Morrison experienced a similar transformation.

“Oh yeah, because it was mainly American GIs, y’see, that you were playing for,” he remembers. “They were hip and they knew all the music. They were hip to the whole thing so they would kind of give you some suggestions, introduce you to the music. So you were getting it first-hand. There were no black American professional singers out there, but some of these guys that weren’t professional were actually very good singers. Where could you get that experience? You couldn’t get it in Belfast at that time.”

Morrison’s musicianship took a distinctive turn in Germany when an (almost) unknown soldier introduced him to the distinctively agitated, thumb-strumming electric guitar style that features in some of his most compelling performances, the current rendition of Motherless Child being a key example.

“I didn’t really have a guitar role model. What I picked up was from this guy in Germany that played guitar called Lee Reed – I never saw him again. He was a black guy who hung out with us in Germany. He came up on the stand, grabbed the guitar player’s guitar and was playing this stuff with his thumb and I thought, ‘Okay.’ I sort of picked up on that and that became my style.”

As a vocalist, Morrison’s horizons broadened too when one of the GIs gifted him a 45 of Bobby Bland’s Stormy Monday. Gradually featuring more and more Ray Charles and R&B in their set, The Manhattan morphed from showband to full-blown R&B band during their German sojourn. While still primarily a horn player, Morrison’s vocal influences continued to grow.

“It was Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley originally. Then it became, when I started getting more into singing, Sam Cooke. Not the ‘la di da’ commercial stuff but the other stuff, the stuff they weren’t playing on the radio. Gospel stuff, the Night Beat album, B-sides and things. Also, Jimmy Witherspoon. I saw him live round that time at a club in London. I forget the name of the place, it could have been anywhere. He was backed by the Harry South Trio and he just really blew my mind apart – I couldn’t believe it. He has gotta be one of the best singers that ever existed – his timing, his phrasing, everything.”

A jazzy bluesman or a bluesman with jazzy skills – either way Witherspoon was a singer after Morrison’s heart. The pair united on a memorable 1993 US tour captured, in scintillating form, on the brilliant 1994 live album A Night In San Francisco. That album also featured John Lee Hooker, Junior Wells and James Hunter among the guests in a full-tilt R&B review. The full flowering of an idea seeded in London in spring 1964 when Morrison decided to bring the blues back to Belfast had arrived.

“I was in Camden Town with The Manhattan Showband after Germany,” he says. “We were playing what’s called the Electric Ballroom now, something else then [The Buffalo]. This guy came on stage and said, ‘Go check this group out at Ken Colyer’s Club.’ We thought, ‘Oh yeah?’ so we went to Club 51 [just off Leicester Square, and currently being converted into a themed block of luxury apartments] and it was The Downliners Sect, and they were doing what was basically my record collection. So I just went back to Belfast and decided this can be done.”

Joining with the remnants of The Gamblers to form Them, setting up the historic residency at The Maritime didn’t happen immediately. “This is another myth. It took time. Quite a while, actually.”

Morrison’s talent was partly hereditary. His mother was a good singer but never wanted to be professional. His father and friends played music at home, not in public. It had been necessary for Morrison to leave Ireland to discover what a live blues club could be.

“There was no blues scene in Belfast then, no,” he says. “I started the blues scene – there wasn’t any before that. There was a blues singer called Ottilie Patterson who joined Chris Barber’s band – she was probably the first blues singer to come out of Northern Ireland, or Ireland. But she’d already left. Apart from that, no one was doing it. I was the first to do R&B, and there was a piano player in one of the trad bands, Jim Daly, who played blues. He was the real thing – he’d been to Chicago, played with Muddy Waters. He knew the stuff.

“I did my first solo gig with Jim Daly at Queen’s university in ’66. Like Solly, he was a family friend. My cousin actually played harmonica with him.”

The connection held strong, and at an invite- only 1990 pre-Christmas show at Belfast’s Errigle Inn, Daly’s Trio accompanied Morrison on a roaring, red wine-fuelled blues set.

Them’s greatest recordings stand with any from the R&B beat boom. Highlights include Morrison recasting Dylan on It’s All Over Now Baby Blue; fusing Magwitch from Dickens’ Great Expectations with a Bo Diddley beat on the blistering Mystic Eyes; channelling Bert Berns’ pop R&B in excelsis on Here Comes The Night; and, of course, Gloria, the B-side that became a global garage-punk anthem. But Morrison’s memories are clouded.

“It quickly became very complicated once the Solomon Brothers became involved,” he explains. “It became complex. Something very simple to begin with… then we got involved with the contracts and all. They were the in-between for Decca Records, the production company that signed us. So then it became a whole mess very quickly.”

In the past Morrison has said The Maritime was where the group really lived and died. Attendees remember unforgettable performances – Morrison rolling on the floor, jumping on tables, an extreme, physically engaged frontman.

“Well, it had been very physical before, when we were kids and we were playing rock’n’roll at a place called Chamberlain Street, a corrugated iron hut,” he says. “We played there every week, and there was a lot of leaping around all the time so this was nothing new. Very physical wasn’t anything new for me. That’s why I ended up standing still.”

You got too tired?

“No, not too tired. Because everyone else was doing it, people were saying, ‘You’re copying so and so.’ I would say, ‘I’m not copying anyone – I was always doing this.’

So the way the press were writing about it was the problem?

“I was going, ‘Well, fuck you then,’ and I’d stand still and sing. So that’s what happened.”

Was it easier to sing that way?

“No – harder. It’s actually harder – it’s more focused. It worked better because you have to evolve more as a singer. You couldn’t depend on the physical thing – you just depend on your voice, and that was it. I had to keep evolving as a singer.”

Evolve he certainly did, and meeting musical heroes was a key part of the process. Chess star Little Walter gave him harmonica lessons. “Only a few – I could never come up to the standard of Little Walter,” he says. “He was Little Walter, the best harmonica player who ever existed. He was very relaxed and laid-back when I saw him back at the hotel. He didn’t say very much to me – he just wanted me to go for Chinese food. So, I went for Chinese food and was asking him about the harp.

“He opened his case and showed me this chromatic [harp] and said, ‘This is what I’m into now.’ He picked up this huge harp and started to play really complicated stuff and he said, ‘Why don’t you play a bit?’ So I did this Sonny Terry thing and he went, ‘Man, I don’t play that John Henry shit any more,’ y’know? He was putting me down. But he was great. I actually played guitar on a gig with him. He hadn’t a guitar player that night and he took me along, just playing rhythm guitar.”

It was during this time that Morrison first met John Lee Hooker too, forming a friendship and musical association that endured throughout the boogie man’s career, until his death in 2001.

“It was ’64, ’65 in the Aaland Hotel Bloomsbury [London] when I first met him. It was just like breathing, I used to listen to him. I wouldn’t be that presumptuous as to play with him. He was in the lounge just playing acoustic. I just used to sit and listen. It was mesmerising. Mesmerising.”

Jimmy Page famously played uncredited lead guitar on Them singles during his session man career, but Morrison wasn’t put out by that. Quite the opposite, in fact.

“Jimmy played on everything then. He’s playing rhythm guitar on Here Comes The Night and he’s playing on Baby Please Don’t Go. He’s playing a detuned six-string guitar, so he’s actually doubling the bass part, then when it drops down low he’s playing this thing behind the vocal – it’s a tuned-down guitar but it sounds like a bass.

I loved it. Why would it piss me off? It didn’t bother me at all. There really was no band – by that time the band was disintegrating anyway, so there was only a couple of guys and myself that were left. No, that didn’t piss me off at all. That was somebody else, somebody put me in an interview saying something that one of the other guys said. Maybe one of the others was pissed off but I loved it.

“I loved the drummers, too. There was Alan White and Bobby Graham, who were both great. You could learn something from these people. Why would you be pissed off?”

Them’s career came to an end in Los Angeles in 1966, their final hurrah including a show with The Doors and Jim Morrison, with Van jamming with his namesake on elongated versions of Gloria.

“I’d double over when they did Alabama Song. They used to kill me when they did that. I was just doubled over laughing, I couldn’t believe it, it was so weird. I didn’t know the song at all. I thought they were having a laugh, it was such a weird song. They would do Back Door Man and then do that… you’d think, ‘Okay, this is different.’”

The Lizard King’s performances made a lasting impact. “Ah, he was great. He didn’t move about that much but he was acting – a great method actor, that’s what he was. It was drama, basically. The whole thing, drama.”

Morrison had previously described his own performances as akin to method acting, but today he fine-tunes that description. “The dynamics of being able to do it, I’d say it’s more like ritual than drama. A non-religious ritual.”

Back on stage at Cyprus Avenue in 2015, all Morrison’s years of learning and paying dues came to bear in spectacular fashion. The set embraced his history and influences, and Sonny Boy Williamson’s Help Me was there, as it invariably is. After his own Moondance and Gloria, it’s the song he’s performed on stage more than any other (843 times according to the unofficial but exhaustive Vanomatic website). What’s the key to its enduring appeal?

“I don’t really know,” he admits. “I just always connected with it from the first time I heard it. I mean, totally connected with it. I can’t explain why. It’s like John Lee Hooker said, ‘I can’t explain what it is. It just is.’”

Jim Morrison was acting – a great method actor, that’s what he was. The whole thing was drama.

We’ve been talking for nearly an hour and a half and Morrison indicates he’s starting to tire. One of his management team, Graham, has been sitting nearby throughout and he asks if we can wind up. Just back from playing shows in Canada, Morrison and he have business to discuss – there are follow-up releases to the recent Duets: Re-working The Catalogue album to be organised and scheduled.

There’s still a bounty of unreleased live and studio material in Morrison’s archives, and he’s spoken of doing a straight blues album, but nothing is finalised at the moment. Plans can go awry, promising business relationships can turn sour. In a BBC Radio 2 documentary last year, Morrison told broadcaster and sometime band member Leo Green of his disappointment that during his time with Blue Note in the noughties, the label failed to deliver on a proposed big band album.

Despite the accolades, the knighthood and his astonishing performing consistency, Morrison still feels his deep blues get overlooked. “There’s a lot of blues songs I’ve recorded that nobody knows about. Like Too Many Myths, Big Time Operators, Goldfish Bowl, Fame, Keep Mediocrity At Bay. I can’t remember them all. More of the adult themes are not addressed because people always want to go back to the stuff that was done in the late 60s or early 70s. That wasn’t even my reality at the time – it’s hardly going to be it now. But there seems to some kind of conspiracy against, I don’t know, telling the truth. Don’t ever tell the truth about the music business or how it really is, y’know? People say, ‘You’re against the music business.’ I’m not against the music business at all. I’m just talking and writing about my experiences. I don’t have anything against any of it, I just have my truth and I’m saying it.”

When you write a song that’s a blues, are you in a particular frame of mind?

“Well, usually it’s stressed or just plain pissed off, really. Like in Too Many Myths, just trying to stay in the game. People think it’s this way and assume these things about you that aren’t true – that song was simply about that. They want to superimpose their interpretation on your reality, no matter what you’ve lived. They aren’t really concerned about your reality. People go, ‘But what are you talking about, you’re trying to stay in the game? You are at the top of this, top of the tree.’ Well, that’s as may be, but whether you’re on the top, the middle or the bottom, it’s hard to maintain this, wherever you are.”

Do you feel a duty and a responsibility to the music, to carry it on?

“Maybe, yeah,” he considers. “You’re responsible once you put your name up there. You can hide behind a group name, you can hide behind

that, but once it’s your name up there, you’re responsible for all of it, good or bad. So I guess from that point, you feel total responsibility.”

You finished the Cyprus Avenue show with the rap about the eternal presence and it “always being now”. Does recreating the blues anew each time you perform remain a focus?

“Yeah, it does actually, that’s right. Well, it’s the thing that keeps me connected. It’s harder to get that in the studio nowadays, I don’t know why. Maybe studios are more complicated now. I find it’s better live. Maybe it’s because there’s an audience as well. That puts more pressure on it. You have to just get on with it and do it. Whereas I think in the studio it’s become very complacent. They aren’t really good environments for making music any more, I don’t think.”

Can’t you create your own studio?

“Well, you can, but I don’t know what that would be now,” he says. “When I started we were recording live. So you’d rehearse it and do it live. There was no overdubs, no 24-track boards. That was it – you just did it, usually in-between doing gigs. So it wasn’t a complicated thing. Now engineers don’t know about this stuff. Some people are actually afraid of it. They don’t understand it. When we started, that’s how it was because they came from a different era. We would think of the performance and then get it down, but they think the equipment is the most important thing. It’s not. Performance is the most important thing, not the equipment.”

When you get tired of the blues, just put on Howlin’ Wolf. You’re not going to be tired any more.

The time to end the interview is nigh. It doesn’t feel right to press on further. Since I first saw him perform in 1982 I’ve seen Van Morrison perform more than any other artist. Those one-of-a-kind, non-religious rituals, those endless affirmations of the blues’ enduring power – there’s no one like him. He’d already given me enough, long before he walked into the Portobello sitting room.

Asking for a selfie feels inappropriate too, so I ask him to sign a copy of Lit Up Inside. I also mention Mick Green, The Pirates guitarist whose playing propelled 1999’s Back On Top, Morrison’s outstanding end-of-the-century blues set.

Green’s presence augured in a particularly purple period of Morrison’s live performances. At a filming of Jools Holland’s Later… the axeman was in spectacular form and Morrison knew it. The studio floor filled for Gloria’s climactic encore with members and friends of fellow guests Blur, Wilco, The London Community Gospel Choir. The camera stopped rolling but the pandemonium rose even higher when Morrison gave him the nod and Green’s guitar was let loose.

Morrison remembers the occasion well, proudly noting that another guest, Southern soul queen Candi Staton, elected to provide backing vocals.

“Mick Green, yeah, I really miss Mick Green –

he was so good, unbelievably good,” he says fondly. “Mick was something else, totally unique. Been there since the beginning. There is no one like that any more. See, it was fun going in the studio with him, but that all seems to have died out. These people are not around any more. You can’t really replace somebody like Mick Green – he’s irreplaceable. So where do you go from there?”

Such weariness and despair have long been part and parcel of Morrison’s blues-based world view, but there’s something that can always perk him up.

“I never tire of the blues,” he’d said earlier. “Especially if I go back and listen to some of the stuff, it’s still amazing. I mean, Howlin’ Wolf. You get tired of the blues, just put on Howlin’ Wolf, y’know? Then you’re not going to be tired any more. There’s so much energy there – he lights you, really lights you up.”

Top 10 Van blues collaborations

RAY CHARLES – CRAZY LOVE

Morrison recorded this Moondance ballad with the high priest for the latter’s 2004 Genius Loves Company duets album. A live pairing features on 2007’s Best Of Van Morrison Volume 3.

BUDDY GUY – FLESH & BONE

Featured on the Chess guitar legend’s latest album Born To Play Guitar. “Buddy is one of the last people who does the real stuff,” says Morrison.

JOHN LEE HOOKER – NEVER GET OUT OF THESE BLUES ALIVE

“That was just ‘show up and do it’ – I was ad libbing a lot of my part. But we did that a lot, never the same kind of thing twice, making it up on the spot,” Morrison recalls.

CHRIS BARBER – OH DIDN’T HE RAMBLE

A New Orleans standard recorded in 1976 but not released until 2011’s Memories Of My Trip, where it was one of three collaborations with Morrison.

GEORGE MELLY – BACKWATER BLUES

A 1927 blues anthem concerning a flood disaster provided the focus for this 2006 tribute to Melly’s heroine Bessie Smith, released on the late, great writer and raconteur’s Ultimate Melly album.

BOBBY BLAND – TUPELO HONEY

Honoured in Them’s cover of Turn On Your Lovelight and Ain’t Nothing You Can Do, Bobby Bland recorded this with Van at Bristol’s Wool Hall studios in 2000.

JIMMY WITHERSPOON – LONELY AVENUE

This 15-minute medley turns the Doc Pomus song into a rolling epic, Morrison’s fierce delivery providing a magnificent contrast to Witherspoon’s velvety insinuation.

BB KING – EARLY IN THE MORNING

Louis Jordan’s blues standard was recorded in London in spring 2005 and released on the BB King & Friends album later that year. Matching King’s gruff vocal glory, Morrison’s aching mouth harp gilds BB’s quicksilver guitar too.

MOSE ALLISON – PERFECT MOMENT

Allison’s droll songwriting was such a key influence that Morrison recorded a whole album of his songs, Tell Me Something, in 1996, joining with the great man himself for this self-descriptive closer.

THE BAND – 4% PANTOMIME

Featuring a vocal summit with the late, great Woodstock-era drinking buddy Richard Manuel, this featured on The Band’s 1971 album Cahoots.

Van the showband man: How Morrison paid his dues on the Northern Irish live circuit

Van Morrison’s earliest publicity picture features him in the front row of The Monarchs’ nine-piece line-up. The toothsome grins, matching trousers, socks and jackets place the band firmly in the then-popular showband tradition. First named in 1955 by Belfast- based orchestra leader Dave Glover, these bands featured cover versions and variety turns.

Like cross-border contemporary blues enthusiast Rory Gallagher, teenage Morrison had no choice but to find a way toward playing the music he loved via the showband scene. In a short stint with rival outfit The Olympics, Morrison learned a hard lesson in showband audience expectations when his rendition of Blue Suede Shoes brought one Saturday night country dance to a stunned silence.

In The Monarchs he got with the programme, suitably garbed to perform knockabout sax routines on Neil Sedaka’s I Go Ape and The Coasters’ Yakety Yak. With a different band of the same name holding sway across the Irish border, the now International Monarchs moved further afield, even recording a one-off single in Cologne.

Back home in Belfast in early 1964 after The Monarchs split, Morrison failed to persuade several pals to leave their respective showband slots to form an R&B band. Then an offer came from his old pal Billy McAllen to join The Manhattan Showband. With Van and his madcap older pal Geordie Sproule on the bandstand together, The Manhattan pushed at the edges of showband acceptability. Indeed some of their playful-cum-surreal routines still get referenced in the knockabout call-and-response routines Morrison features in his contemporary set.

Being based in a part of Ireland predominantly identifying as British may have favoured Morrison’s desire to explore life beyond the showband cultural straitjacket. The Manhattan’s setlist extended to allow covers of songs by The Beatles, and Manfred Mann’s proto-R&B chart-topper 5-4-3-2-1.

Down south of the border, the band incensed audiences and club owners alike. In Drumshanbo, County Leitrim, a particularly testy audience inspired a composition later released on the Philosopher’s Stone collection.

The end of Morrison’s time in the peculiarly Irish showband tradition came to a close when The Manhattan travelled to make a St Patrick’s night appearance in a London Irish pub. What he witnessed in the big city would light the touchpaper for Them’s R&B revolution at The Maritime. But it’s fair to say that Morrison’s performing identity still owes something to the long-gone showband scene.

Duets: Re-Working The Catalogue is out now via RCA

Late NME, Daily Mirror and Classic Rock writer Gavin Martin started writing about music in 1977 when he published his hand-written fanzine Alternative Ulster in Belfast. He moved to London in 1980 to become the NME’s Media Editor and features writer, where he interviewed the Sex Pistols, Joe Strummer, Pete Townshend, U2, Bruce Springsteen, Ian Dury, Killing Joke, Neil Young, REM, Sting, Marvin Gaye, Leonard Cohen, Nina Simone, James Brown, Willie Nelson, Willie Dixon, Madonna and a host of others. He was also published in The Times, Guardian, Independent, Loaded, GQ and Uncut, he had pieces on Michael Jackson, Van Morrison and Frank Sinatra featured in The Faber Book Of Pop and Rock ’N’ Roll Is Here To Stay, and was the Daily Mirror’s regular music critic from 2001. He died in 2022.