Sex, death and Lulu: the real story of Metallica and Lou Reed’s explosive collaboration

Metallica and Lou Reed’s Lulu album is still metal’s most controversial collaboration. This is how two unlikely worlds collided

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

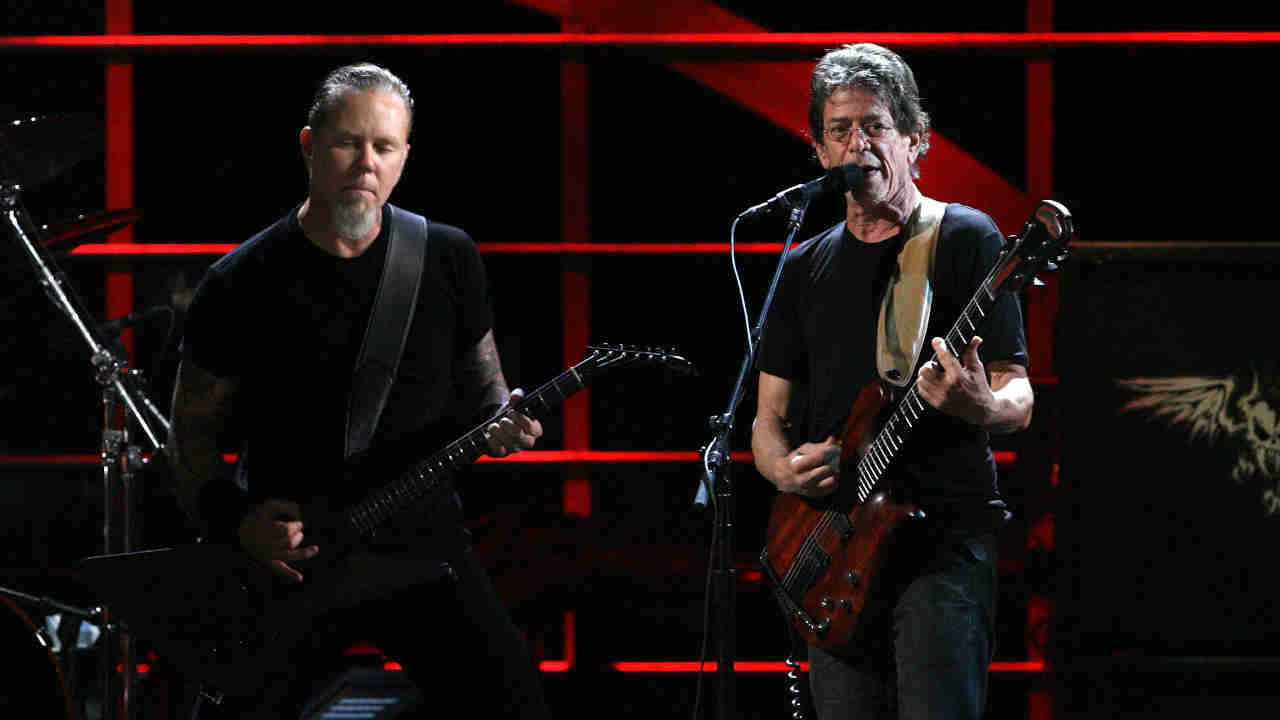

As I’m thrust into a suite at Claridge’s with four cameramen plus a girl pointing a fluffy boom mic up my nose, the sight of Lou Reed, James Hetfield and Lars Ulrich sitting on sofas opposite is oddly reassuring.

Freaky, and faintly terrifying, obviously, but reassuring to the degree that the story that Lou Reed and Metallica have made an album together, based on two relatively obscure plays much admired by Sigmund Freud, may not have been the deranged fantasy of an internet rumour-monger on disagreeable steroids. Like a restricted view of Mount Rushmore, the three rock gods stare at me, silent, impassive, possibly a bit knackered on this opening day of promo. Someone mutters, “Good to go.” To ease us all in, I ask the obvious question; predictable, entirely non-confrontational. So, I say mildly to a safe mid-point between Lou and James and Lars , how did this surprising collaboration come about?

“Why?” rumbles a gruff voice from deep within Lou’s bowels. He’s a small man, frail, 69 years old. He moves carefully. But when he glares at you, believe me, you stay glared at. “Why is it surprising?” barks that leathery, bespectacled, iconic face.

Uh… two different genres… merging…

“And that’s surprising? Who would say that?” We’ve been going 25 seconds. I’m not convinced it’s going well. Then again, Reed once told me an interview had “started well, but now your questions suck”, and in 2004, when I asked if he was clean-living these days, drawled, “Oh, I’m smoking a fucking crack-pipe as we speak, can’t you tell?” So, you know, maybe this is promising. He demands to know which specific people on which specific websites have said this collaboration is “surprising”. Instinctively I start answering back, just random words really, realise I have no idea and that anyway this isn’t the point, then turn around to the director filming the interviews and suggest we take this from the top.

- On a budget? Here are the best budget turntables

- Best headphones 2020: supercharge your music listening

- Spotify vs Apple Music vs Tidal: which streaming service is best for rock and metal?

Lou, suddenly an impish, naughty little boy, goes, “But I only got to ‘Why?’ I was going to then move to where, when, in which language – English? Danish? In Esperanto?” There’s a twinkle in his eyes and he’s working hard not to laugh. “Go on,” he decrees. “Carry on, this’ll be good.” He all but winks. He’s just messing about. (Half a century of picking fights with interviewers must be a hard habit to break. “I’ve hidden behind the myth of Lou Reed for years,” he once said. “I can blame anything outrageous on him. I’m so easily seduced by the public image of Lou Reed that I’m in love with Lou Reed myself.”) From here on, he’s a pussycat, talking at length and with smarts, even out-talking Lars, which is unheard of. When we’re done, he chats for 10 more minutes about his recent solo shows. Beneath the bravado, he’s delicate, like a bronze head atop a body made of rice paper. Rising slowly to leave, he shakes my hand four times.

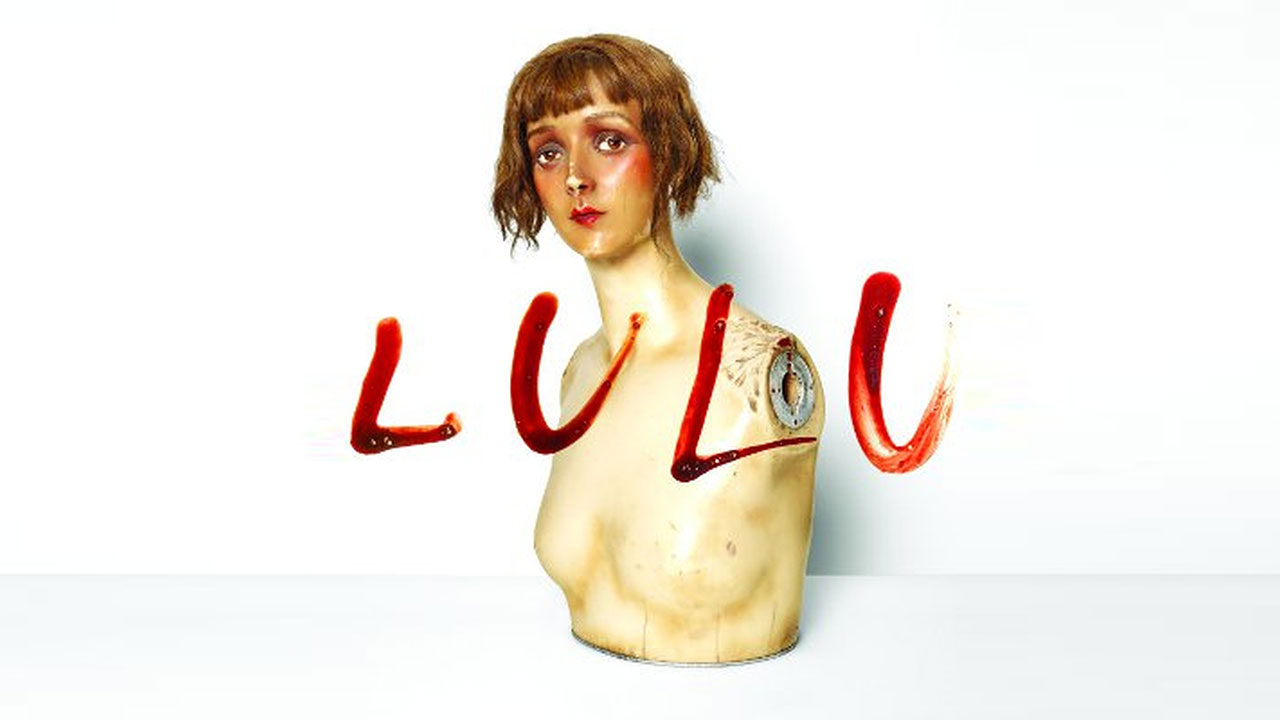

During the bulk of the interview the unlikely alpha trinity of Loutallica are at ease (if a little overtly “After you… No, after you, I insist”), singing each other’s praises, the air thick with mutual respect, all on message that Lulu is happening. Like it or not, believe it or not, it’s well and truly happening. “My Lulu had a head,” says Reed today, “but she needed a body.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

- Every Metallica album ranked from worst to best

- Master Of Puppets: how Metallica made the greatest metal album of all time

“It’s not a party record,” he observes. “It’s not one of those: ‘Hey baby, you sucked my dick, now let’s do a line of coke and get a tattoo on the weekend and see you later at grad school, hurrah.’ He pauses.

“Okay,” he muses. “So it’s not that.”

The venerable dark prince of New York avant-rock made unconscionably influential music with The Velvet Underground in the 60s before becoming a solo star on the back of Bowie collaboration Transformer and has since released a stream of diverse albums, from the punk tangent Street Hassle to the cacophonic Metal Machine Music, channelling the spirit of Burroughs and Poe. It’s safe to say that he thinks. Metallica, the world’s best-selling thrash-metal band have been wrangling speed and volume to shape sound in new ways (Ride The Lightning, Master Of Puppets) since forming in California in ’81. It’s safe to say that they rock. Today, Reed mentions in passing Tennessee Williams, David Cronenberg and the composer Strauss. James Hetfield says of the album, “We got to stamp ’Tallica on it, y’know? To make it heavy.”

Lars says a lot of things, admittedly after turning to the others and politely saying to them, “Shall I do the spiel then?” “Yeah,” says Lou, “you’re so good at it.” “Oh, thank you!” beams Lars, “and that’s coming from you!” I also talk to guitarist Kirk Hammett and bassist Rob Trujillo, who are equally enthusiastic. “On paper it does look strange,” says Kirk. “No one else in the heavy metal world has done anything like this. It’s a new animal.”

“It’ll definitely freak some people out,” says Rob, “and that’s good.”

If you think about sex, death and alienation, and you probably do, the album isn’t so very unlikely. Both parties have consistently dealt with these subjects lyrically, just with contrasting skill sets. The clash-marriage-collision-bonding of the two has delivered something as startling and strange as you’d expect, only more so. It works (and works you hard) on visceral and cerebral levels. Its 90 minutes of noise and neuroses are inspired by the Lulu plays (Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box), written by German expressionist Frank Wedekind. These plays, (set in the 1890s and published in 1895 and 1904 respectively) hugely controversial then and scarcely less so now, flash between the points of view of Lulu (a seductress-victimEve-mirror) and her lovers and abusers. There’s plenty of sex. Also, Jack the Ripper shows up. Director choreographer Robert Wilson hired Reed to come up with lyrics and songs for his modern theatrical production in Berlin (a city close to Reed’s creative heart since his brilliant 1973 album of that name). Overriding another mooted plan, Reed, in Ulrich’s words, “asked if we were game. And we’ve been forever touched and changed by the experience.”

“We wanted to add to the potency,” says Hetfield, “to make it rock.”

“This is the best thing I ever did,” announces Reed, “and I did it with the best guys I could possibly find on this planet.”

How, though, did these new best friends meet, plan to record, and then retain the focus, some time later, to get together and do it? Lars does the spiel. They first came together in October 2009 at the 25th Anniversary of the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame concerts, Metallica playing Sweet Jane and White Light/White Heat onstage at Madison Square Garden with Lou, who declares, “We knew from then that we were made for each other.” According to Lars, Metallica had been invited to represent “the left-field artists, the outsiders”. Reed was “top of our list to collaborate with. He’s like a solo version of Metallica, always done his own thing, reinvented himself, challenging not only himself but his fans.” It felt “effortless”.

- You might not rate St Anger, but it single-handedly salvaged Metallica's career

- We got Ghost's Tobias Forge to pick his dream Metallica setlist

Lou then suggested that they record together. Metallica “ran around the world three times” finishing their Death Magnetic commitments, and were “ready”. Lou’s first idea was to record “some lost Lou Reed jewels,” continues Lars, “and we’d do whatever it is we do to those songs.” That strategy hung in the air awhile. A week or two before sessions were to begin, Lou called up and sold them his “Lulu” plan. The band were intrigued, Hetfield happy to “take off my singer and lyricist hat and concentrate on the music, to put our ‘stamp’ on it”. (“Stamp?” laughs Reed. “It’s branded. And it’s not coming out.”)

Kirk reveals that the band was much happier with this arrangement, it being a spontaneous collaboration rather than Metallica playing on already-established songs: “We bowed to the magic.” Lars talks of being “psyched” by the structureless nature of Reed’s songs and of “inventing the wheel”; Hetfield of a “blank canvas”. They’ve tried before, they say, but never been this “far out there”. It was “authentic, impulsive… an exciting ride to be on.”

If there is any area in which the happy gang don’t quite have their story straight – and you have to squint to find it – it’s the slight gap between Metallica labelling the material Reed brought along as a “blank canvas” and Reed’s notion of them as songs. Put this down to everyone enthusiastically claiming credit: it’s honest, boyish zeal all round rather than ego-niggling. That he gave them “atmospheres, sound-scapes” seems to be the consensus, and they fleshed them out. (And lengthily – most of the 10 tracks are in the region of 10 minutes; Junior Dad runs to 19.)

Reed laughs heartily when I ask Metallica if the project took them out of their comfort zone. “Have you heard their comfort zone?” he says. He’s not reluctant, however, to emphasise that the ball started rolling with him. After one speech, it dawns on him that he’s hogging the interview, and he says to Lars and James, “I’ll stop, I’ll just stop…” “I’m enjoying everything you’re saying!” beams Lars. “Keep going! Ha ha!” Only the faintly awestruck “ha ha” hints at an excess of eagerness to please. “I’m enjoying it too, it’s good stuff,” I say, but in truth the three of them are performing for each other, demonstrating how into it they are, barely aware I’m still here. When later I’m signalled to wrap things up, Lars says, “Oh give yourself five more minutes, man!” James murmurs dryly, “We’re talking here. It’s a wonder anything gets done!”

- Jerry Cantrell says James Hetfield is the greatest frontman in metal and we're not about to disagree

- Metallica Mondays: Your ultimate guide to every show

“I’d worked on this thing for a while,” affirms Lou. He gives a back-story of the “immoral, no, amoral” play: how shocking to the bourgeois it was in its day “which I guess is why Wedekind wrote it”. He describes Lulu as the great “femme fatale”. Lou got what he calls his “paws” on it, and spent time fathoming the narrative with “my significant other, Laurie Anderson”. It didn’t come easy. “We had to figure out Lulu’s psychology, to bring her to life in a sophisticated way, but using rock.” He wanted “the hardest power rock you could come up with” and “Metallica live on that planet. Dream come true.”

He sent Lars some roughs. James says, “We sat there with an acoustic guitar, listening, and just let it take us where it needed to go. It was a great gift, starting from scratch.” Lou stays silent but his presence abides and James switches horses midstream. “Well, there was a body of work there, very potent lyrics, and… we got it together very quickly.” Lou turned up at Metallica’s HQ studios in California in April and, says Lars, “by lunchtime, we were fucking deep in it. Jamming, playing, throwing paint at the canvas. Happily and hopefully all the ‘record’ buttons in the cockpit were on.”

Whereas Metallica are notorious for spending ages in preparation, agonising over every riff, Lou’s rigid stares would let them know that the extended improv they’d just let loose with was a “take”.

“It was intuitive,” adds Lars, “I mean – 30 years here, but it was just so exciting to just… go. To just feel it, to respond to what was going on.” Work was finished in under a month.

“They said: let’s go, let’s do it, can’t wait,” says Lou. “I’d been submerging my psyche in Lulu and the various characters, and in the studio we’d examine this further. It’s not always Lulu singing; in my mind I’m switching gears, characters. It’s not easy. It’s like: what happens if you try to bring the whole thing up to the level of Selby, Poe, Burroughs, Inge, Tennessee Williams? There’s an argument that if you have to think, you can’t rock. But the mind is the most erogenous zone I know, so that’s an unusually dumb comment.”

James enjoyed the fact that there was “another powerful force in the room.” After a feeling-out period, “I’d think: I maybe don’t like that part, but should I say something? I don’t want to shut the door on stuff because I’ve been called Dr. No for 20 years. Now I’m almost the opposite, I couldn’t stop saying yes! We needed to agree that this was just awesome. Who’s steering the ship at that point? The moment is. Let go of that fear of no control, and you’re in heaven. So many great ideas coming at once: don’t mess with them. Celebrate that. A wonderful problem to have.”

- “Whose f**king idea was this?”: how Metallica’s made the spectacular S&M2

- Dave Mustaine reviews Metallica's Hardwired… To Self-DestructJerry Cantrell says James Hetfield is the greatest frontman in metal and we're not about to disagree

“Lou’s very literate,” says Kirk. “He doesn’t take any shit,” says Rob. Kirk adds that the band tuned their guitars down “to C” to give Lou more range vocally. “That helped him greatly.”

Asked if there were happy accidents, Lars says, “The whole thing was one happy accident after another.” James says, “There’s no accidents here. This was supposed to happen. I absolutely know that.” “Oh, me too,” concurs Lou. “We happened to kinda meet by accident, but again, there’s no such thing as an accident. I don’t think we ever disagreed about anything. It was just five guys trying to do this thing, whatever it was.”

Whatever it is, it’s not, as Reed rightly points out, a party record. With its unblinking beat lyrics and rants of jealousy, lust, violence and revenge, and its grinding riffs, tantalising tones and taxing drones, it’s a turbulent, caustic, gruelling, exhausting, uncompromising 90-minute voyage into…

“I wouldn’t call it the heart of darkness,” muses Reed. “I’d call it the heart of illumination.”

“It could be disturbing,” suggests Rob. “At the same time, it could be beautiful. It’s a marriage of attitudes. The very idea of Metallica improvising, literally, was new territory for us. So I personally feel that Lou’s made us a better band, more creative, which will definitely help us in the future.” “It’s next level,” says Kirk. “I hope our fans embrace it with an open mind. We’re kindred spirits. Mesh us together, it creates something graphic, cinematic and heavy.”

“There they were,” declares Lou. “Pushing me to the best I’ve ever been. By definition, everybody in there was honest. You say it’s an ‘odd’ collaboration? An ‘odd’ collaboration would be Metallica and Cher. This is an obvious one.”

“Lou knows,” says James, “I’ve been searching for something like this for a while. We needed it.”

So is it a one-off? Will this go down as one of rock’s most historic triumphs/debacles? Or are these loved-up best buds, these contrasts-in-arms, in it for the duration?

“We never go that far in our thinking,” says Reed. “It’s enough to me that we’re even on this planet. This thing has been shepherded into the world unsullied and will go out the way it came in. Pure. This is a new genre here, and we punch it out. This is where I like to exist.”

Published in Classic Rock #164

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.