How The Pineapple Thief made Magnolia and entered a new era

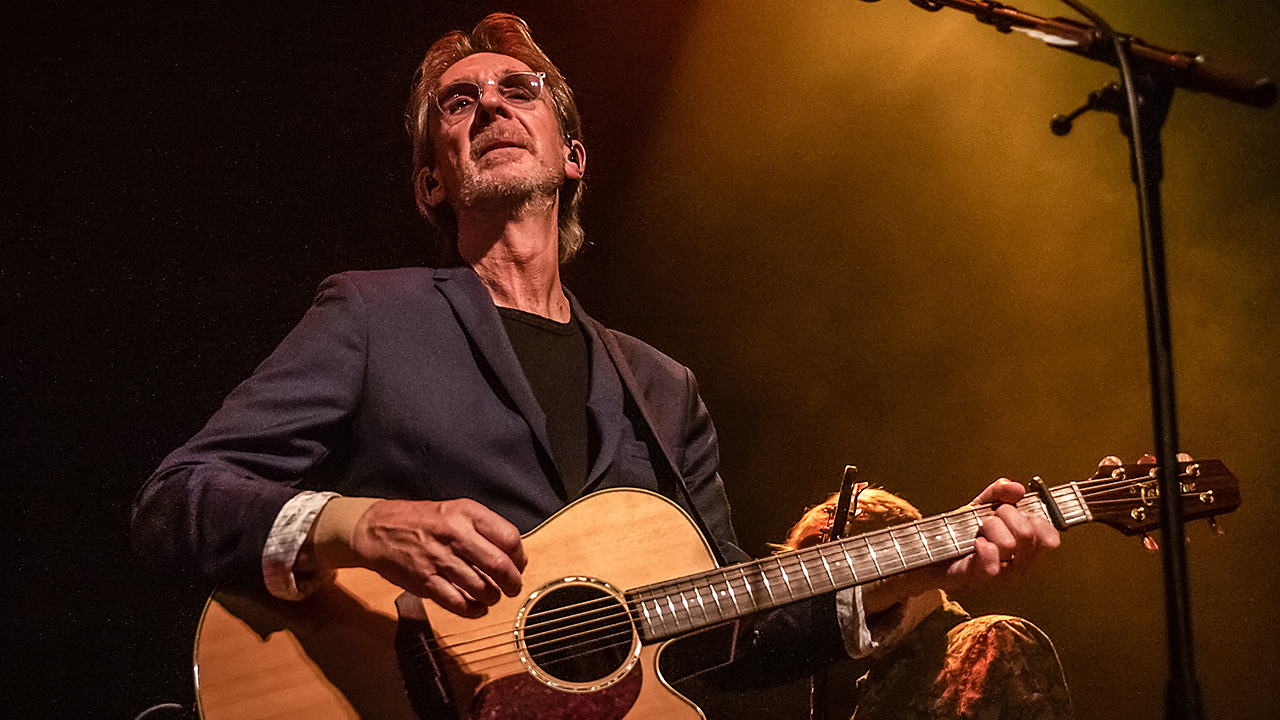

The Pineapple Thief's frontman Bruce Soord reveals the liquid inspiration, loss and life behind their 2014 album Magnolia

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Something’s changing in prog. Call it modernisation, call it a periodic shake-up, call it evolution… actually, ‘compression’ might be better. Or the dawn of the ‘post-epic’ age, if you will. Conceived boundaries of prog have been questioned, refreshed and sexed-up for a number of years now. Record label Kscope have played a major role, housing staples of the contemporary prog glitterati including Steven Wilson, Anathema and today’s focus, The Pineapple Thief. Dare we say it, this magazine has played its part in expanding prog horizons beyond the ’70s Yes/Genesis/ELP core, while still holding those guys close to our hearts. But most recently, certain acts have veered from the long-held ‘epic’ format, opting to contain lush, progressive imaginations within tight song lengths. Leading the charge are The Pineapple Thief, brainchild of Bruce Soord.

“For me personally, there’s a breed of progressive musicians who are trying to define ‘progressive music’ in a different way,” Soord says. His broad-minded curiosity makes sense, given that his CV now spans The Pineapple Thief, Wisdom Of Crowds, an acoustic stint with prog-metallers Katatonia and early ventures with extreme metal. “So yeah, I’d like to think there’s a new, credible, exciting progressive sound coming out. All I’ve really cared about is doing something which sounded fresh and new, but still had everything I love about progressive music.”

Moment of disclosure: Soord is probably one of the nicest interviewees you’ll ever come across. Not that other rockers are cyborgs by contrast, but the Pineapple Thief frontman is unquestionably ‘real’ in person; relaxed but switched-on, in a friendly, gently buzzing sort of way. He’s also really tall – unlike many famous types, who turn out to be surprisingly short in the flesh – and strolls into Kscope HQ with the look of a man just returned from the Caribbean. He hasn’t been in the Caribbean, just his Yeovil home in Somerset, though he does tan at the drop of the hat, courtesy of being “a bit foreign” (his dad came from Burma, via India, before meeting Bruce’s English mother).

‘Everything he loves’ comprises the depth, arrangements and intrigue that are synonymous with good prog. On 2014 album Magnolia, none of these are compromised – just compressed into immaculately formed, progressive vignettes, vitalised no end by the arrival of drummer (and production whizz) Dan Osborne. “He admits he’s got special needs because he’s so focused and becomes so involved,” Soord grins. “He pushed me on the performances so far that I just wanted to punch him in the face sometimes.”

Faces intact, the finished Magnolia is arguably more potent in its shorter songs, and remains luxurious amid lush string arrangements from Divine Comedy man Andrew Skeet. It’s an attention-commanding career moment for a band whose previous records all included at least one ‘epic’. The final effort with label Cyclops, What We Have Sown (a ragbag but beguiling collection of cuts from Soord’s studio floor) ended with a 29-minute beast, for crying out loud.

“When I put the tracklist together at the end of Magnolia, I was like ‘Shit, there’s nothing over five minutes,’” he remembers, eyes widening in mock shock. “Traditionally, people in the prog world go on about their ‘epics’ – as if it’s mandatory, if you’re in a progressive rock realm, to have an epic tune. But I think as I’ve grown older, and maybe wiser, I’ve just found I could say what I needed to say in a shorter space. So whereas before I would write a song and think, ‘Okay, now I’m gonna put in a middle section and make it go on and on, and then I’m gonna have a euphoric outro and that’ll go on for about four minutes…’”

He laughs a little. “I don’t need to do that any more. I’ve done it and I’m bored of it now. So even though the songs are shorter, I still feel there’s a lot going on.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The condensing process began, to a degree, with 2012 LP All The Wars. Fans lapped it up, critics were largely pretty ecstatic, yet Soord, ever the perfectionist, straight away describes it as “a difficult album”. Post-production problems dragged the process out for about five months. It was, he says, “a painful mix”, which left frustrations in want of resolving. “With Magnolia the production is much stronger,” he explains. “Some of the songwriting [on All The Wars] I look back on and think there were things about it that I wouldn’t let go of. Why did I do that? Why did I take that song in that direction? But then again that’s because I’m different now. I’m three years older than when I wrote those songs. Every songwriting process is at least 12 to 18 months. It takes ages. It’s a weird kind of torture.”

The torture lessened massively with Adam Noble on mixing duties, who had previously worked with such prog greats as, erm, Robbie Williams. Nevertheless, having initially brought him in to perfect the drum sound, Soord bonded with Noble over a mutual love of Beck – specifically 2002’s Sea Change album – and hired him to mix the whole record. “It was the first time I’d ever given that away and trusted someone with it,” Bruce smiles. “In fact, with this album I think I’ve trusted more to other people than ever before, which was a big risk and I lost a lot of sleep over it.”

Ultimately, however, it was this decision that freed up the necessary creative headspace (“That does sound wanky, I know, but that’s how it was!” he chuckles) for Soord to devote more focused time to the actual songs than ever before. Ideas were developed at home on an acoustic guitar – contrary to the techy impression one may glean from The Pineapple Thief’s electronic elements (and ‘nu-prog’/Kscope era association), he’s not one to leap on to a laptop at the first signs of a song.

“It was such a relaxing experience,” Soord smiles, “which is completely the opposite to how All The Wars went.”

Thematically, however, The Pineapple Thief have never shied from unrelaxed, darker matter, nicely offsetting atmospheric swathes and pretty vocal melodies. 2005’s Little Man, for instance, articulated the pain of Soord and his wife losing a child at birth (they went on to have twins), All The Wars conveyed fraught regret and love, and much of Magnolia arose from similarly sombre territory.

“And I was probably drinking too much,” Soord concedes, with a knowing look. “But the truth is, the best songs on the album were when I was in the studio, probably late at night, having drunk too much. Obviously at any other time in the recording process, alcohol is a terrible thing. But on the songwriting side, for some reason the best stuff came out when I was in this dark place. Which I really wish wasn’t the case, but it’s the truth.”

A number of songs stemmed from the sudden loss of close friend Steve Coe, formerly of ’80s prog/world act Monsoon, who proved a pivotal kindred spirit and mentor for Soord.

“He was so pure about it, he wasn’t interested in any money. He’d just phone me up with ideas and he’d edit new arrangements and play them for me. And we were going through the album like this, and then…”

Soord pauses, clearly not on the verge of tears, but looking quietly sad, “he basically just dropped dead.”

Listen to the almost classical, orchestral feel of From Me and the sense of loss is especially tangible. “I wrote that after going to Steve’s funeral,” Soord says. “Because trying to put any kind of sense to it just seemed impossible. That’s why it starts ‘This makes no sense’, because that was all I could think. But at the same time, even though it’s dark and a little bit morbid, I still feel like it’s cathartic for me.”

And that’s a lovely thing about this – and pretty much all of The Pineapple Thief’s records. Despite the dark notions, it doesn’t feel like a depressing album. The title track especially is beautifully tragic, without being heavy handed. It’s delicate, with Soord’s Thom Yorke-tinged vocals, and stirring too, as crescendos swell to leave every hair on the back of your neck sprung to attention.

“I always say to people that I write about the darker side of life, but the contradiction is that I absolutely love life,” he beams. “I’m not religious or anything like that, but I absolutely adore waking up every day and living life. So I like to think that comes across.”

Soord is a thoughtful soul, but with a zingy musical geek streak conceived in his teens. Disenchanted in the late ’80s by new romantic hits, along with Stock, Aitken and Waterman smothering the airwaves with “terrible, terrible pop music”, the young Soord turned back to the ’70s to find “some interesting music – progressive music, basically”. And as The Pineapple Thief prepare to present Magnolia to the public, he hopes to fulfil similar cravings within today’s generation.

“I still think there’s a mass market out there of kids who, if they knew this kind of contemporary prog existed, would go out there and buy into it,” he says earnestly. “Porcupine Tree were doing it before. If you went to one of their gigs, the range of the demographic in the queue was huge. You could see that Steven had managed to cross over to these kids that loved it.

“But I’m wondering, is the [contemporary prog] scene coming of age? Is this the second coming of progressive music, in a way? Am I on the edge of it? I hope so. I mean, judging by the audiences that we’re getting… I’m not saying I don’t want the older generation coming to gigs because I do, I love them to bits! But when I see a lot of the young kids coming through, it feels really great.”

This begs the question of whether Soord, on some level, wrote such shortened material on the new album with the specific view of reaching more (maybe younger) fans?

“It’s a really good question, because the motive is to write music, of course,” he muses. “But the other motive is that I want to share my music with as many people as possible. I’d hate to think that that was ever going to influence the way I wrote a song, thinking, ‘We’ve got to reach a new audience, let’s do an instantly catchy song to drag people in so they can then discover the rest.’ And maybe that did influence me, I don’t know. But at the end of the day, I like a decent catchy tune as well.”

He has no issue with admitting that the goal, for all of them on Kscope, is ultimately much the same as any ‘commercial’ act – to sell as many records as possible. “A lot of people when they hear Magnolia, they go, ‘Sometimes I think you’ve found this sort of new… commerciality!’” he says, feigning an appalled gasp, before laughing, “As if this is a dirty word! And I say, ‘I don’t care! As long as it's good, I’m happy.’”

It’s just a shame that such ambitions don’t come cheap. Magnolia cost about twice as much to make as All The Wars, with investment in the A-list skills of Noble and Skeet, as well as recording string sections with top-end players (fresh from touring with Peter Gabriel) in London. There’s no way round it – the band are now completely skint. “We’ve got no money, and we’re going to have to sell three times as many records to recoup our costs, so… for us, yeah, we do wanna sell more records!” Soord laughs. “Because unfortunately you need money to be able to function, and taking the band on tour costs money…”

Indeed, the flipside to The Pineapple Thief’s activity is that they all have to do other work to pay the bills. Bruce does production and mixing for other artists, keyboardist Steve Kitch runs a mastering business, and bassist Jon Sykes is an engineer “building things that go on satellites”, Bruce explains. “I think he’s working on some space telescope at the moment.”

It’s hardly a rare situation, in today’s band climate, but for Soord it’s all worth it. While Stateside touring is a costly prospect (though they do have fans there), enthused Pineapple Thief crowds in Europe are commonplace these days. “So it’s coming together now. I mean, with the tour we’re doing in November, if it goes well, we make money. If it doesn’t, we lose money. So it’s a roulette wheel, but it’s exciting!”

With an album of hard-hitting songs to showcase, a sparkling line-up capped off with newbie Dan Osborne on drums, and Soord’s live experience with Katatonia last year (learning 17 songs in the process, both guitar and vocal parts), The Pineapple Thief are well equipped to deliver on their upcoming winter tour. This lavish spread of skills seems a far cry from Soord’s homespun early days. At college and school, at weekends while their contemporaries were out getting trashed, Soord and a friend would hire a drum machine and a four-track and write death metal songs.

“And Jonas [Renkse] and Anders [Nyström, of Katatonia] were doing the exact same thing at the same time!” he reveals.

Still, from teenage experiments with extreme metal outfit Dominus (they never gigged), Soord moved on to duo Vulgar Unicorn, and subsequently The Pineapple Thief – initially a solo venture, in which he did battle with a synthesizer. “I remember buying my first synthesizer and setting it up and not having a clue how to work it,” he says fondly. “And in those days studios at home were quite difficult. It wasn’t a case of ‘buy a computer, put ProTools on it, all your sounds are already there.’ I was there all day and night trying to make it right.”

Still, come Variations On A Dream in 2003, he’d assembled a band to support Canterbury legends Caravan at a festival slot. It was a shock afterwards to find a giant queue at the merch stand, demanding Pineapple Thief CDs. It was a seminal moment, realising his bedroom project had serious legs. “So when I look back on little old me on my own in the studio, I do occasionally allow myself to smile and think, ‘Yeah, it’s gone alright.’”

In the aftermath of recording, life can function at a slightly less fraught pace – a pace that can, at last, incorporate football. “I’m like a not-very-skilled Robbie Savage,” Soord grins sheepishly. “I run around annoying people, running and running because I’m quite fit. But playing football is such a release because you’re not thinking about anything else. You’re thinking about that ball. Whereas when you’re writing songs, all you’re thinking about 24 hours a day is that song that’s in your head.”

Otherwise it’s all about listening to music, maybe knocking up a good curry in his kitchen in Yeovil.

Ultimately, the album-rooted lifecycle continues: release, tour, attract new followers, start writing again, repeat. “I don’t think I could ever see that routine stopping,” Soord admits. “I think I’d go mad if I didn’t write.”

He pauses, looking ready to say something deeply philosophical. “Until I start writing absolute trash, and then someone needs to tell me ‘Bruce, stop it!’”

This article originally appeared in Prog 49.

Polly is deputy editor at Classic Rock magazine, where she writes and commissions regular pieces and longer reads (including new band coverage), and has interviewed rock's biggest and newest names. She also contributes to Louder, Prog and Metal Hammer and talks about songs on the 20 Minute Club podcast. Elsewhere she's had work published in The Musician, delicious. magazine and others, and written biographies for various album campaigns. In a previous life as a women's magazine junior she interviewed Tracey Emin and Lily James – and wangled Rival Sons into the arts pages. In her spare time she writes fiction and cooks.