Steven Wilson: Time Flies...

Wilson has branched out as a solo artist, but may go back to his Porcupine Tree roots...

It’s been five years since they last played together, yet the subject of Porcupine Tree’s reformation remains a prickly one for the group’s founder, Steven Wilson. Now, with a new box set revisiting their classic albums, prog’s figurehead reveals all about his band’s past – and whether still they have a future.

Nostalgia is a mischievous beast. Even as he further consolidates his reputation as modern progressive music’s most revered and successful exponent, Steven Wilson finds his unerring forward momentum to be intermittently subject to a strange sense of regression.

As prog has become less of a dirty word and more something the rock mainstream will at least consider as worthy of their time, the ongoing absence of the band that kick-started the genre’s renaissance in the first place remains a big talking point. Porcupine Tree ceased activities in 2010, not long after the release of grand conceptual opus The Incident, allowing Wilson to focus on his solo work. But despite many subsequent triumphs, the question he finds himself answering most often is: “Will you ever bring Porcupine Tree back?”

Speaking to Wilson today, it’s obvious from his wry smile and a faint rolling of the eyes that he regards discussing his old band as something between a necessary evil and a nagging pain in the neck that no amount of Ibuprofen can shift. But there’s a new box set to consider: The Delerium Years 1994-1997, a compilation of expanded versions of classic albums The Sky Moves Sideways, Signify and live set Coma Divine. It also fulfils the very specific purpose of richly illuminating the moment when Porcupine Tree transformed from a tentative but increasingly potent bedroom side project into a fully fledged rock band.

The music itself is as vivid and exciting as it was two decades ago, but as much as Wilson has skilfully tinkered with old music by other artists, this step back in time is obviously not his prime concern in 2016, not least due to the release of new mini-album 4 ½. That said, he’s also fully aware that his growing profile as a solo artist can hardly fail to revive and increase interest in the Porcupine Tree legacy. It’s a complicated business.

“There’s no question to me that Porcupine Tree is bigger now than it was when we stopped,” he shrugs. “I think part of it is that absence makes the heart grow fonder. The legend grows in your mind. I’ve always admired the fact that there are certain bands that have never reformed, because it’s always disappointing. Maybe not the Led Zeppelin one-off, but every other reformation I can think of has a sense of ‘Oh, fantastic, they’ve reformed!’ and the shows sell out instantly, but afterwards people say, ‘Hmm, they weren’t as good as they were first time round…’ Well, what did you expect?

“I think it’s better to just to let that legend exist in the memory, and that certainly seems to be true with PT. But also, the sound of that band has become quietly quite influential and it wasn’t something we were really aware of at the time. It’s only in the last six or seven years that it’s become apparent to me that whatever we were doing, or what I was trying to do with that band – that hybrid of metal and melodicism and a Floydian, intellectual core – I suppose was quite unique, and I hear it in a lot of bands now. So that’s very flattering, but it doesn’t make me want to go back now and do it again.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

His resistance to nostalgia’s backward gravity should surprise no one. Throughout his career, Wilson has made a point of remaining sonically restless and perpetually open to the thrill of the new. Luckily, memories of the mid-90s aren’t too hazy for most of us, and even without that prior knowledge of Porcupine Tree’s early work, the music in the new box set confirms that Wilson’s modus operandi has remained consistent for a long time. And while he admits that this retrospective release would have emerged whether he wanted it to or not, his meticulous attention to detail in the studio, not to mention a zealous enthusiasm for the limitless possibilities of recorded sound, are writ large across newly remastered versions of these revered relics.

“Yeah, I’m a control freak,” he laughs. “I felt for some time that I needed to remaster the albums, because the previous masters I did in the early part of the 21st century were over-compressed, over-EQ’d, as was the trend at the time, to make everything as loud as it could be. I regretted it in recent years. I can’t stop Kscope releasing these things so I thought, ‘Well, let’s make them as good as they can be!’ So we’re doing two box sets. The second one will cover the ’91‑’93 period, the solo years. This is the band years.

“I can’t say I like a lot of the music. I’m really proud of some of it but I was very inexperienced and the production’s not good. It was recorded on primitive equipment by today’s standards, and it sounds like it. It sounds a bit nasty and digital, so I’ve tried to get some warmth and vibrancy back into the music.”

“I think there’s a strong possibility that Porcupine Tree could do a new record, in our own time and for fun, and maybe do some shows too.”

There are moments when it suddenly seems better to not have Steven Wilson’s razor-sharp hearing. From a fan perspective, and perhaps with a little dash of that pesky nostalgia thrown in, The Sky Moves Sideways and Signify are cherished classics.

To their primary creator, they were tentative steps along a new road, as the solo experiments of 1993’s Up The Downstair and its hypnotic sibling Voyage 34: The Complete Trip mutated into the sound of progressive rock’s wholesale rebirth, with all the guitars, bass, drums and bluster that such a bold move seemed to demand. With hindsight, turning Porcupine Tree into a band could hardly have been a smarter decision, but it was one that Wilson was initially reluctant to make.

“I was very resistant to it becoming a band,” he nods. “After the success of the first few records, Delerium said, ‘You need to play live!’ I said, ‘I don’t want to. I hate playing live!’ – and I did. I’d done it with No-Man and hated it. But one day they came back and said, ‘Mark Radcliffe at Radio 1 wants you to do a live session…’ and at that point I couldn’t say no any more.

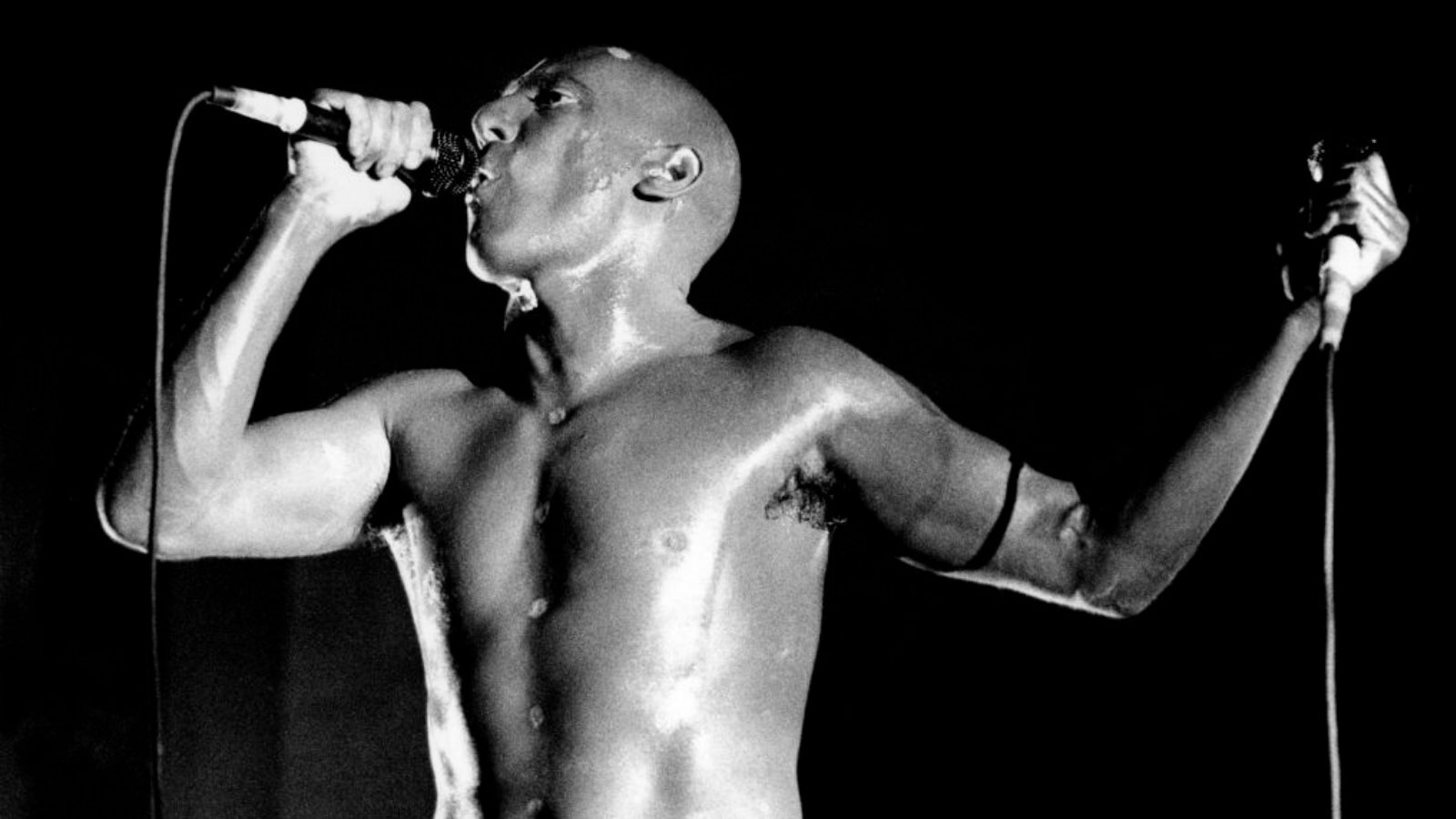

“So at that point I put together the live band for the first time. We did three shows – one in Coventry, one in London and one in Wolverhampton, and then one at the radio station – and I enjoyed it! I thought, ‘Wow, this band’s great!’ I didn’t necessarily like being the guy at the front and singing. I grew my hair long so I could hide from the audience, but eventually I was learning how to be the frontman of a rock band and I was enjoying it.”

Becoming a bona fide live entity made all the difference to Porcupine Tree’s career arc, enabling them to seek out the steadily growing number of music fans that either loved the prog ethos of old or were searching for an alternative to bland mainstream rock. And despite his initial reservations, Wilson was transitioning from DIY obscurity to the rock’n’roll circuit with something approaching childlike glee.

“Oh I loved it!” he grins. “Listen, when I was a kid I wanted to be a pop star like everyone else. I wanted to be on the cover of magazines and hear my songs on the radio and say to my mum and dad, ‘Look, I’m really something!’, you know? I wasn’t the kind of person who was gonna shy away from reaching a bigger audience. In fact, quite the contrary. One of the constant frustrations of my career has been not being able to do that – not being able to reach a wider audience and the prejudice that still exists for this kind of music – so I totally embraced it all [at that time].

“As you can probably tell, one of the things I most love to do is to talk about music and talk about my music. I’ve never had a problem with promoting myself or doing interviews. Point me in the right direction and let me go! So back then, I absolutely embraced that.”

While fiercely focused on his band’s burgeoning career, and seemingly loving every second, Wilson was also quietly and stoically campaigning on behalf of progressive music during the days highlighted by the new box set. As the 21st century dawned, the landscape slowly began to look very different, with a little help from Radiohead’s OK Computer but also from the simple fact that the prog genre began to blossom anew, with Porcupine Tree firmly at its forefront.

Looking back, it’s almost as if the band started their rise to glory in the wrong decade, and that they may have become far more successful had they emerged in the era of Muse’s stadium-conquering exploits.

“Yeah, that’s possible, but I don’t know. How you become hip or not is such an arbitrary, random thing, it seems to me,” Wilson notes with another shrug. “I don’t lose any sleep over it. I always say I would’ve loved to have been born 10 years earlier, because to have come through that crucible of early-70s experimental rock music, I think I probably would have sold millions of records, because the kind of ambition and that kind of experimental, conceptual rock music was at its absolute peak.

“The 90s was probably the worst possible time to be trying to make that kind of music… and yet, as I’m saying that, I’m thinking back to the 90s and there were bands like The Orb, making this hippie, ambient music, and I loved it. Everything about that is, on the surface, uncool, except perhaps the allegiance to techno and electronic music. And I think that’s the key to it. If you have that electronic element, you can get away with a lot more pretentiousness. So here I was, basically in what was an old-fashioned rock band, and I think that was a count against me.”

Fast forward two decades, however, and demand for a Porcupine Tree reunion is greater than ever. Not that anyone with functioning ears is likely to discourage Steven Wilson from continuing his solo career, but whether through stubborn nostalgia or because the band’s music continues to resonate with and influence so many aspiring musical adventurers, it seems unlikely that requests for a reconvening of the classic PT line‑up will ever stop arriving in Wilson’s inbox. And that line-up, lest we forget, also included Colin Edwin, Richard Barbieri and Gavin Harrison.

“I think Porcupine Tree, over a period of time, developed a sound, and that’s a good thing,” he states. “One of the things about the band is that we’d make you think of a particular sound and it did become quietly influential in its own way. But by the last record I wasn’t sure what I could do any more with that band, that ideology, that philosophy.

“One of the things about being in a band is that it’s a democratic thing. That’s why I envy Mikael [Åkerfeldt, Opeth] in a way. He can do whatever he wants and the band go along with him. Porcupine Tree wasn’t like that. If the guys didn’t want to play something, they’d say, ‘I’m not playing that!’ And that’s fine, you know? [Laughs]

“We can’t always agree, so you go in a direction that you’re all happy to go along with. You don’t want someone onstage sulking. That’s the last thing I wanted, but a couple of the guys were very good at sulking when they didn’t enjoy something! So I think the expression ‘painted into a corner’ comes to mind. If we’d made another record after The Incident, it probably would’ve been a lot like The Incident and we’d have the law of diminishing returns and I think, at the very least, that we had to stop for a while.”

Five years have passed since Porcupine Tree wound down, and while Wilson’s solo work shares many characteristics with his former band’s music, it’s the freedom he now enjoys that seems to be the deciding factor in his resistance to reuniting the old gang.

“I didn’t necessarily like being the guy at the front and singing. I grew my hair long so I could hide from the audience.”

“One of the things I love about mixing these early King Crimson albums is that they used to like to use jazz, really experimental free jazz like Keith Tippett and those guys, and I wanted to do something like that, and that’s why I made Grace For Drowning,” Wilson explains. “But there’s one guy in Porcupine Tree who absolutely loathes jazz, and he’d take the piss out of the very notion of it. That’s fine. I have objections to certain kinds of music too. But then you think, ‘So, I can’t do that, so what can I do? More of the same?’ There’s this little area where you all cross over and it’s the kind of music we all wanted to play. Over time, they all got a little bit more power [in the band] because I gave it to them, but also because I felt less prepared to be the dictator. I did a solo record and having got to that point, I realised that I enjoyed this more now, so why would I go back to Porcupine Tree?”

And was everyone alright about that decision at the time? “Yes. But I don’t think they thought it would be as long or as seemingly permanent as this.”

Ah. Seemingly permanent. There’s a glimmer of hope in there somewhere, isn’t there? Perhaps more than any other contemporary musician, Steven Wilson pointedly and proudly represents a progressive mindset that’s instinctively opposed to backwards steps and comfort zones, and yet he’s not ruling out the possibility that, at some point when he’s not furiously busy with any of his myriad projects, Porcupine Tree might just be worth revisiting. Until then, the new box set offers an enhanced view of the past, but as always, it’s the future that most concerns Hemel Hempstead’s finest.

“If I’m honest, I’d say that if there was a new Porcupine Tree album, it would be a side project for me now. There’s no way I would go back to the band as my full-time job. But having said that, I think there’s a strong possibility, a strong argument, that Porcupine Tree could do a new record, in our own time and for fun, and maybe do some shows too. I’m not going away on the road for a year again. I’m happier now as a musician – for all the complaining I’ve done in this interview [laughs] – than I’ve ever been. I’m basically doing exactly what the fuck I want and I have an audience that seem to go with me, and it’s still growing. But do I think it would be lovely for the fans for us to do something at some point? Yes.”

The Delerium Years 1994-1997 and 4 ½ are both out now on Kscope. For details, see www.stevenwilsonhq.com.

Four (and a half) play…

Before solo album number five, Steven Wilson teases us with a mini-LP of unreleased and reworked tracks.

As if he hasn’t been prolific enough over the last few years, Steven Wilson is following 2015’s Hand. Cannot. Erase. and recent vinyl compilation Transience with the release of 4 ½. This self-proclaimed “interim” effort comprises songs recorded during sessions for Wilson’s last two studio albums, plus a brand new and radically different version of Don’t Hate Me from Porcupine Tree’s 1999 album Stupid Dream.

“I’m a great believer in writing more than you actually need and then cherry-picking… not necessarily the best songs, but the songs that have the best flow, the best continuity,” Wilson explains. “These songs were written for one of the last two records but they weren’t left off because they weren’t good enough, but because they didn’t fit in with the stories. It’s like a movie. You’ve got a scene and you love the interaction of the characters, but it doesn’t really progress the story and it slows it down a bit. That’s true of these songs too. I really like them and I didn’t want to throw them out as bonus tracks because I thought they were too good.”

Four of the songs on 4 ½ hail from sessions for last year’s Hand. Cannot. Erase., and while they work perfectly well as stand-alone tracks and in collective form, they all exude the same sense of unease and isolation that made the album such an absorbing experience.

“Yes, four of the songs are connected to the last album. The female lead from the album does occur, certainly in My Book Of Regrets on this record. In a sense, I always write the same song anyway!” he laughs. “I’m being facetious, but there’s an element of truth, in that every songwriter ultimately ends up writing about the same things throughout their career. We’ve recorded a new version of Don’t Hate Me, and that’s also a song about the loneliness of living in a city, so I discovered to my horror that I’ve basically been writing the same songs, or songs that deal with similar subjects, for years!”

He may have loosened up when it comes to revisiting his PT past, but Wilson remains dedicated to realising the next great idea, rather than relying on past glories. The new version of Don’t Hate Me is markedly different from the original, both in terms of production and arrangement: an upgrade rather than an update.

“Don’t Hate Me was a song I always loved and Porcupine Tree didn’t play it live very much. I guess that also added to this feeling that it was my song and not necessarily a Porcupine Tree song. The band’s reaction was a bit ‘Do we want to do that? Nah…’ But I always really wanted to do it,” Wilson recalls. “When I listened to the studio version I felt like we took it a little bit too fast, so I slowed it down a bit and it feels a little more lonely. It was also written very much as a duet, with the chorus sung by a different person from the verse, so finally I’ve been able to do that, with Ninet [Tayeb, who also featured on Hand. Cannot. Erase.] singing the chorus and me the verse.”

Given how prolific he’s been in recent times, it seems unlikely that 4 ½ will be Steven Wilson’s only release of 2016. He is, of course, already working on material for the full-length follow-up to Hand. Cannot. Erase., and while it’s far too early to predict where his freewheeling solo career will go next, he does imply that fans of his heavier material may be in for a few extra treats this time round.

“One of the very conscious decisions I made when I started my solo career was to get away from metal and move more towards exploring things like jazz, which I definitely did on Grace For Drowning, and things like the music I grew up with, like new wave bands, 80s bands like Cocteau Twins and Wire and XTC, and I explored that on Insurgentes.

Then there was The Raven…, which was kind of my homage to the original 70s progressive rock. And HCE was really the first time that I went a little bit back to what I was doing with Porcupine Tree, which was almost to bring in all of these elements, including, for the first time in a while, a little bit of metal riffing. It’s almost like now I’ve left it for a few years, I can enjoy it again. I’m writing now for my next record and yeah, there’s a little bit of it in there too. Some big rock riffs, for sure!” DL

Dom Lawson began his inauspicious career as a music journalist in 1999. He wrote for Kerrang! for seven years, before moving to Metal Hammer and Prog Magazine in 2007. His primary interests are heavy metal, progressive rock, coffee, snooker and despair. He is politically homeless and has an excellent beard.