How heavy music saved me from my ADHD brain

Can heavy genres like punk and metal offer solace for neurodiverse people? One Metal Hammer writer shares her experience

Earlier this year, Distillers frontwoman and all-round badass Brody Dalle revealed on her Instagram that she’s been on medication for her inattentive ADHD for four years. Hearing that the woman who was my teenage hero also suffers from the same developmental condition that caused me such feelings of isolation, frustration and anxiety growing up was poignant. Even now, at 31, it made me feel validated, and I realised that she music she created may have spoken to me for a reason.

A post shared by Brody Dalle (@nerdjuice79)

A photo posted by on

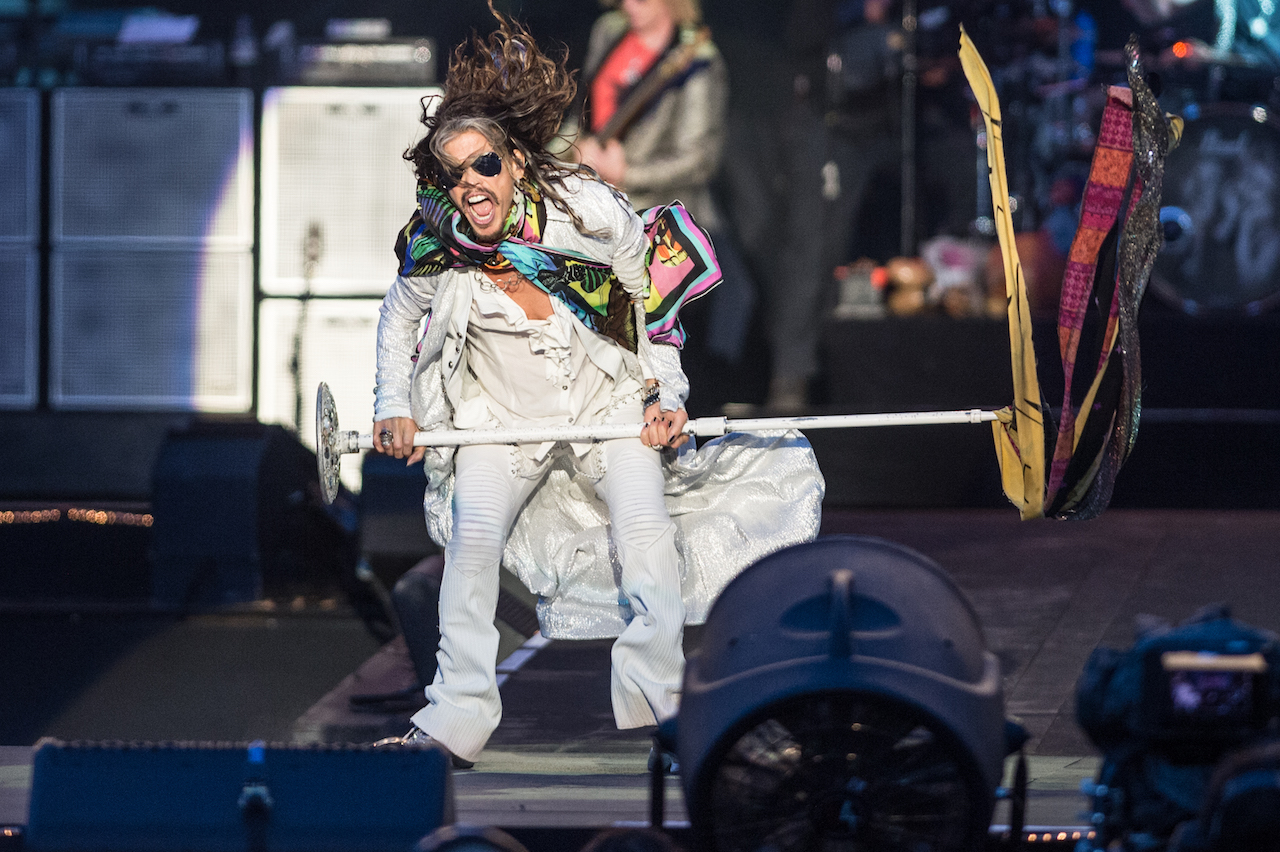

It’s incredible how many of my favourite musicians as a teen were also fellow ADHDers: Kurt Cobain’s ADHD is well documented, Courtney Love has battled with Adderall addiction and all three members of Green Day reportedly struggle with ADHD. Other rockers with ADHD include Stephen Tyler, Joe Perry, Dez Fafara, Brendon Urie, Dave Grohl, and reportedly the Prince of Darkness himself, Ozzy Osbourne. Heavy music was so important for me in managing my ADHD symptoms growing up, and it got me thinking: are us neurodivergent types particularly drawn to heavier sounds?

Being neurodiverse means that our brains learn, process information and generally think differently to the mass majority, who are known as neurotypical. Neurodivergents include those who are diagnosed with ADHD, autism, Tourette's syndrome, dyslexia, dyscalculia and dyspraxia, to name a few.

I wasn’t diagnosed with ADHD until I was 24, but the symptoms have plagued my entire life, from being an imaginative, daydreaming kid through to my anger-fuelled teens and beyond. ADHD has a whole host of symptoms, and it can be hard to explain them to neurotypicals when you have always seen the world through ADHD-tinted lenses.

I am often lost inside my own head, and with so much going on inside, the outside world can appear hazy. If I have something I need to do – from making a phone call to writing an article like this one – I am a master at procrastinating. In fact, it’s amazing how productive I can be in avoiding a project. But beyond avoidance tactics, I just find it almost impossible to focus. I grew up being told I just “wasn’t putting my mind to it”, and thinking I must just be lazy – but if I am so lazy, why am I always so tired?

My ADHD is like constantly being in a state of fight or flight. My adrenaline is pumping 24/7, making it hard to focus, sleep or sit still, and I am in a more heightened state of anxiety than everyone else. It means everything is exhausting, yet I have too much energy – my head is running round and round in circles and my body is struggling to keep up.

With a brain like that it’s no surprise that at the core of ADHD is executive dysfunction. This means that I appear forgetful and disorganised. My thoughts reel off too quickly to filter them. I’ll often lose my train of thought, and common words and phrases will disappear from my mind mid-sentence. I can seem too intense and fast-talking to some, while my crippling anxiety (caused from years of bullying and being berated for my forgetfulness or perceived thoughtlessness) and hyperactive mind can sometimes make me appear distant, cold or rude.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

On top of this, those with ADHD and ASD suffer with emotional dysregulation. This can often manifest as low frustration tolerance and rejection sensitive dysphoria. Any form of rejection or criticism can cause an emotional reaction in me that others would deem extreme. When I feel any emotion, I seem to feel it ten fold, and my brain will obsessively hyperfixate on things that bother me. Like with Autism Spectrum Disorder, those with ADHD are also prone to sensory processing issues, causing outbursts of emotion which are often met with hostility and offence. All of this can make it hard to feel understood and maintain relationships.

For me, all of these symptoms led to one thing: anger. I had pent up frustrations from years of feeling isolated and from feeling that I lacked the ability to just function as other people seemed to. Everyday life felt exhausting and unnecessarily difficult.

Enter Tony Hawks Pro Skater and the 90s teen movie soundtracks that introduced me to punk rock. After discovering the short-lived music channel P-Rock at my aunt’s house and picking up a brightly coloured ‘punk special’ of Kerrang! magazine, I was thrust full-force into the world of mohawks, Dr Martens and spiked leather jackets.

The speed and ferocity of punk rock satisfied my impatient nature. It gave me a productive outlet to vent my rage, air the frustrations I had about not fitting in, and to let out the extreme emotional reactions that overwhelmed me. Plus, with my aggressively feminist outlook, I loved that punk rock was full of equally angry female role models, who weren’t being berated for their hot-tempered attitudes. Instead of punching walls and trashing my bedroom, I’d blast Die For Your Government and Anti Flag would vent it all for me, allowing me a rare moment of calm.

As I got older I fell down a rabbit hole of heavy, and into the worlds of hardcore, thrash, doom and extreme metal – the ultimate antidote for an overactive, frustrated mind. Without it, I wouldn’t be the person I am today.

My childhood friend Nicole Harris was diagnosed with Asperger’s (a high functioning form of autism) at age 14. Nicole has found that metal helps her in a similar way that it did for me. “Heavy music makes me feel like I’m expressing my emotions in a way that wouldn’t be possible otherwise,” she says. “I’ve just always found it hard to express anything properly. I think I have a lot of emotions and it’s hard to manage them without feeling overwhelmed.”

Dutch writer Wessel Broekhuis was diagnosed with Asperger’s when he was four, and in 2010 he wrote an autobiography about his experiences. “Metal is often about big emotions – aggression, despair, etc,” he explains. “It’s larger than life in many ways, which was great because I could understand these emotions that were so clear, while a lot of emotional expressions that I encountered in daily life among my peers were confusing and unintelligible for me.”

Wessel also finds that metal satisfies his Asperger’s tendencies to obsess over complex topics. Metal and its plethora of subgenres allowed him to indulge his obsessive, “extremely geeky” autistic hyperfixations.

Music is scientifically proven to help ADHD brains. According to ADDitude, a brilliant online resource for ADHDers: “Music is rhythm, rhythm is structure, and structure is soothing to an ADHD brain struggling to regulate itself to stay on a linear path”. Music therapist Kirsten Hutchison says, “that structure helps a child with ADHD plan, anticipate, and react”.

Personally, this resonates with me. I need my music to hold a structure – it may be a heavy, distortion-filled structure, but it’s structure none the less. Interestingly, Dan Watson, an IT consultant from Bristol who was diagnosed with ADHD in his 30s, prefers his time signatures and rhythms to keep him on his toes. “I always liked the mad energy of metal,” he says. “It’s anarchic, it’s like organised chaos. The high-octane intensity of the likes of Strapping Young Lad and Gojira matches the intensity of everything going off in my head.”

Music publicist Luke James Milne feels similar. “My ADHD has a tendency to make me feel mentally restless, always needing some sort of stimulation,” he says. “Where more repetitive genres of music might stagnate quickly for me, causing me to lose interest, there are few things more mentally stimulating than the high-octane, larger than life, in-your-face world of rock and metal. Every drum fill, change in vocal style, time signature change or guitar flourish is a new spark that keeps my attention glued in place. I can't lose focus, because there's so much to focus on.”

He also explains that while emotional dysregulation can throw up some challenges in everyday life, when it comes to music, it’s actually a blessing. “I'm not just hearing or recognising the power, aggression or rebellious intent of the lyrics of a song,” he explains. “I’m feeling them, first-hand, every time.”

For Wessell, metal felt empowering, and helped him to find his feet in a world that seemed alien to him. “It gives me a backbone I’ve often lacked and helps me make sense of the world and push forward in everyday life.”

I agree. The music speaks to you, and gives voice and credibility to the tornado of emotions you feel as a ND, as well as a providing a safe haven in which to express them: the pit.

By the time I was 13, I was attending gigs regularly, and without the live music scene, I can honestly say I would not have met 90% of my dearest friends. At some of my first punk shows, I’d slip in the pools of beer and fall flat on my arse, just to be picked straight up again by a ramble of people. We’d all skank in a circle at ska gigs, linking arms as if we’d known each other a lifetime, but we’d never spoken a word. I also find that, the more extreme the genre, the more friendliness I’ve encountered.

Filmmaker Noomi Spook is in the process of getting her diagnosis, but her experiences heavily mirror my own. “When I met other metalheads I bonded with them in a way that was almost instantaneous and before I knew it, I had a crowd: real friends, people I had something in common with, people who understood my perspective and enjoyed my company,” she explains.

“20 years later I am still really good friends with most of the people I met during this time of my life, and as it happens, most of them have also been diagnosed as ADHD or Aspie. I think there is definitely a connection between the way my brain is wired and the music I like, and it would appear that this is common in my circle of friends too.”

The acceptance I’ve felt thanks to heavy music is unparalleled, and my fellow NDs agree. Wessel puts it perfectly: “How amazing it was to enter a world with clear (unwritten) rules and rituals, such as raising the horns, and the mosh pit and picking each other up. It was both exciting and very comforting, and while I was dead nervous when I first started going to shows – because it was new, but also because of being in big crowds – I immediately felt at home.”

See www.additudemag.com for more about ADHD.