How George Harrison made his masterpiece, All Things Must Pass

Hare Krishnas, Phil Spector and an all star cast: The story of All Things Must Pass, George Harrison’s epic triple LP

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

One weekday morning in early December 1969, George Harrison found himself in a motorway service station near Sheffield, sitting opposite Eric Clapton.

At that point, The Beatles were still officially a going concern. Their album Abbey Road had been released two months before and sold the usual millions. All four Fabs were as famous as they’d ever been; more so in the case of Paul McCartney, whose profile had been boosted recently by the weird rumour that he had been dead since 1966, and secretly replaced by an imposter.

But that day in South Yorkshire, with his face hidden behind a beard and his hair longer than ever, at least one Beatle was successfully going incognito. When a passing waitress stopped and stared, it was at Clapton, not him. “He is famous, isn’t he?” she asked George.

Article continues below“Oh yeah,” George shot back. “That’s the world’s most famous guitarist, Bert Weedon.”

Such was the unassuming start of Harrison’s post-Beatles existence: gigs in the UK and mainland Europe as part of the band that backed Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett, the husband-and-wife duo whose earthy mix of rock, country and soul had endeared them to Clapton when they toured the US with his supergroup Blind Faith. Now, he and George were backing them in such places as Bristol, Birmingham and Croydon.

For George, the fun had started on December 5, 1969, when the tour called at the Royal Albert Hall. “George met me backstage and said, ‘Could I be in the band too?’” Delaney Bramlett told me many years later. “I said, ‘Could you be in the band? Of course you can.’ He said, ‘Could you pick me up tomorrow morning?’”

The tourbus duly made its way to George’s home in Esher, Surrey. “I knocked on the door,” said Bramlett, “and he said, ‘I got a couple of things [to do] and I’ll be ready to go.’ I didn’t think [George’s wife] Pattie liked that – George going off with a bunch of hillbillies. He just said, ‘I’m going on tour – I don’t know how long we’ll be gone.’”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

These were the first live shows George had played since The Beatles stopped touring in August 1966. At the Liverpool Empire, he stepped out of the shadows and told the crowd, “This brings back a lot of memories.” Backstage, Bramlett told me, “there was beer flying everywhere”. That night, when Bramlett got up from his seat in the dressing room to make his way to the tour bus, George grabbed the seat of his new velvet trousers and tore them off. “There I was, running up the street, naked as a jaybird,” he said.

This, then, was not the perma-meditating, self-denying George that some people might have inferred from his more mystical associations. “Oh God, George let his hair down more than I ever saw before or since,” Bramlett laughed. “Having a drink? Yeah! We all were. They introduced me to Scotch and Coke. I took to it real easy.”

By the time they reached Copenhagen – where the band played three gigs, filmed footage of which you can see on YouTube – the touring party was missing the ex-Traffic guitarist Dave Mason, who usually played slide guitar on a song called Comin’ Home. A somewhat nervous George agreed to deputise – and so was born the technique that would increasingly become his musical signature.

While with Delaney and Bonnie, George also began to work on a new song inspired by the Edwin Hawkins Singers’ Oh Happy Day, the gospel single that was a top five hit in the UK and US in the summer of 1969. It would eventually be titled My Sweet Lord, and its signature riff would be played using the slide technique that he began to learn on the tour.

My Sweet Lord was the biggest single from the album that George would record with the core of musicians he played alongside on the Delaney and Bonnie tour: not just Clapton, but bassist Carl Radle, drummer Jim Gordon and keyboard player Bobby Whitlock. This group of virtuosos had backed Clapton on his first, self-titled solo album and – as members of Derek and the Dominos – would go on to create the jaw-dropping Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs. As well as those musicians, there would also be roles for Ringo Starr, Beatles protégés Badfinger, and, respectively playing uncredited acoustic guitar and congas, Peter Frampton and a young Phil Collins.

The album they all worked on had a thrilling sense of a talent suddenly set free, and music that was among the best its chief author ever created. Reflecting both George’s spiritual beliefs and the demise of the most famous and brilliant band in the world, it was called All Things Must Pass.

Though Paul McCartney’s 1973 album Band On The Run and 1970’s John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band run it close, All Things Must Pass arguably stands as the best Beatles solo album. In its vinyl incarnation, its 28 tracks – which include four instrumental cuts, known as the Apple Jam – span three discs. Though some of its songs date back as far as 1966, it is the crowning glory of the period when George found his feet as a singer and songwriter – which, in retrospect, had begun with his best contributions to the White Album and been gloriously revealed with his two contributions to Abbey Road: Something and Here Comes The Sun.

But on his first proper solo album, what his later work for The Beatles had hinted at was delivered in spades: songs of amazing depth and insight, played with consummate grace by the best musicians around, and sung by George in tones that mixed a new creative confidence with a real sense of emotion and vulnerability.

If the Delaney and Bonnie tour had introduced George to the musicians who would form the album’s core band, another set of experiences would define some of the music they worked on. In late 1968, George had visited Bob Dylan at his home in upstate in New York – where the pair of them co-wrote a new song titled I’d Have You Anytime, and George mixed with Dylan’s associates The Band.

In August 1969, he hooked up with them all again, when Dylan and The Band headlined the Isle Of Wight Festival. An all-star band – including George, Dylan, Ringo Starr, Clapton and Ginger Baker – indulged in an afternoon’s jamming at Dylan’s rented house; at that point, George was also inspired to write a song about his friend’s shyness titled Behind That Locked Door.

Ten months later, in May 1970, George met Dylan in New York, where the pair recorded a handful of songs – including, weirdly, an attempted cover of Paul McCartney’s Yesterday – and the countrified If Not For You. Another product of the same sessions, bootlegged for years, before it was included on the 2013 Dylan set Another Self Portrait, was Working On A Guru, a gentle send-up of George’s mystical inclinations on which he played countrified lead guitar that could have been taken from 1964’s Beatles For Sale.

All Things Must Pass was started only a few weeks later, on May 26. The first half of recording was overseen at Abbey Road by Phil Spector, who had recently finished his controversial rescue-job on The Beatles’ Let It Be – including the gloopy orchestral arrangement he stuck on to McCartney’s The Long And Winding Road – and now created a rock version of his Wall Of Sound, by commanding a crowd of musicians that usually expanded into double figures.

George later apologised for “the big production that seemed appropriate at the time”, but in truth, the album’s breathtaking dimensions were all part of what it made it so great. McCartney’s first solo offering had been the kooky, home-baked McCartney; Lennon would weigh in with the unbelievably stripped-back Plastic Ono Band. The fact that All Things Must Pass sounds so huge is still part of what makes it so thrilling: George suddenly and spectacularly revealing his talent, and thereby leaving his two supposedly senior ex-colleagues standing.

Bobby Whitlock recalled Spector complaining that in the UK, he couldn’t carry a gun. George said the producer’s biggest problem was having to “have eighteen cherry brandies before he could get himself down to the studio”. Spector left the sessions in July, returning only for the mixing – an absence George later put down to “a bad time with drinking”.

Thankfully that hiccup never threatened the sessions’ flow – a fact partly traceable to the talents of the musicians George had got together. Most of the former Delaney and Bonnie band – including sax player Bobby Keys and trumpeter Jim Price, soon to become part of the Rolling Stones’ touring set-up – had left the Bramletts after the 1969 tour and formed the heart of the group who toured the US with Joe Cocker in the early spring of 1970, recording the triumphant live album Mad Dogs And Englishmen.

Alongside Bobby Whitlock, they played a meld of rock and soul that was beyond compare. Put them together with such British musicians as Ringo, Ginger Baker, Procol Harum’s Gary Brooker and bassist and close Beatle-friend and bass player Klaus Voormann, and it was always going to soar.

But there was also the small matter of George’s brilliant songs, some of which shone light on the traumatic demise of The Beatles. Wah-Wah was a cry of anger about his vexed relationship with McCartney, which he had written in the midst of the cursed filming of Let It Be. Beware Of Darkness sounded like a glimpse of the toll the break-up had taken on George’s emotions; All Things Must Pass, a song George had demoed during the Let It Be sessions, now seems like a very prescient admission that the game was almost up.

The same seemed to be true of Isn’t It A Pity, which made it on to the album in two different versions – one Beatles-esque and lushly orchestrated, the other featuring Clapton and Carl Radle, and that bit more stripped-back. By way of a tantalising reference to his old band, the first version lapsed into a la-la-la coda clearly meant to evoke Hey Jude. But as with another song titled Art Of Dying, Isn’t It A Pity actually dated back to 1966.

“I’ve always looked at All Things Must Pass like somebody who has had constipation for years and then finally they get diarrhoea,” George later reflected – a somewhat less-than-spiritual encapsulation of the fact now The Beatles were history, both old and new songs were suddenly pouring forth.

And for all the dark, tortured undertones of some of the music, his creative liberation also led to creations that brimmed with real joy: the euphoric What Is Life, I Dig Love, and Awaiting On You All, whose spiritual bliss masked a pretty obvious dig at John Lennon and Yoko Ono, and the two infamous weeks they spent in bed, so as to somehow further the cause of peace. ‘You don’t need no love-in,’ sang George. ‘You don’t need no bed pan/You don’t need a horoscope or a microscope/To see the mess that you’re in.’

The latter song – complete with its chorus of ‘By chanting the names of the Lord… you’ll be free’ – was essentially a companion piece to My Sweet Lord, the song whose creation spoke volumes about the sheer massiveness of the album’s signature sound. “We had two drummers, a bass player, two pianos and about five acoustic guitars,” said George. “I spent a lot of time with the other rhythm guitar players to get them all to play exactly the same rhythm so it just sounded perfectly in sync… The spread of five guitars across the stereo made it sound like one big record.”

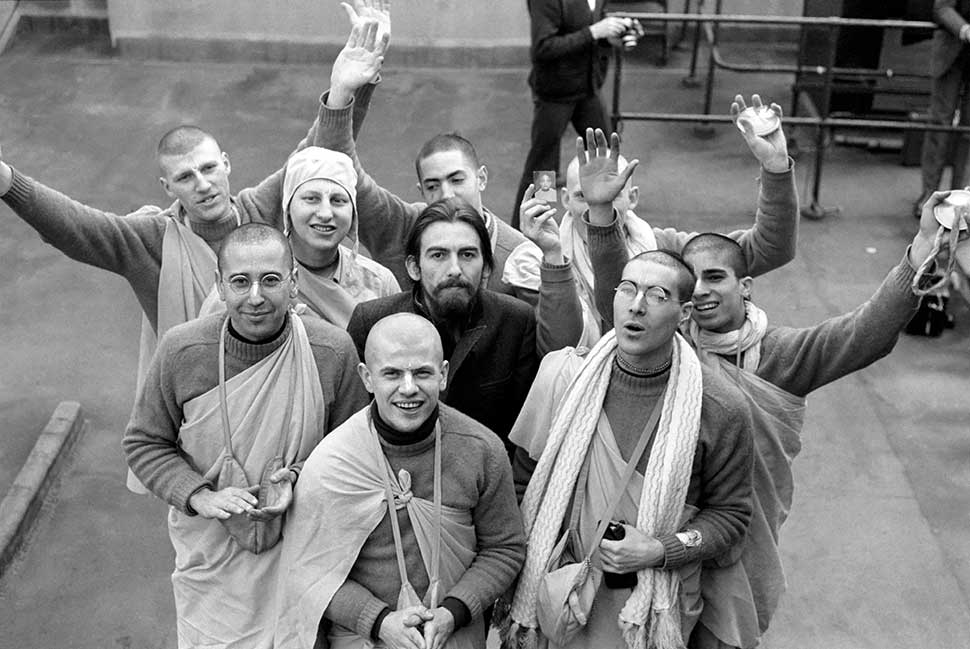

As the album’s great musical edifices took shape, there was only one distraction: a gang of followers of Hare Krishna, the offshoot of Hinduism that George had lately immersed himself in (as evidenced by the transition of My Sweet Lord’s backing vocal parts, from ‘Hallelujah’ to ‘Hare Krishna’). A number of Hare Krishna families were invited to stay at Friar Park, the huge house and estate in Henley-on-Thames that George and Pattie moved into in March 1970.

Bobby Whitlock later claimed that some of the devotees’ children came close to drowning in the estate’s fountains, thanks to their parents’ conviction that whether they lived or died was down to a higher power. Less alarmingly, the Hare Krishnas also intruded on the sessions at Abbey Road.

“At one session, we were halfway through one of the tunes, and a Hare Krishna guy jumped out of the piano,” said Badfinger’s drummer Mike Gibbins, employed at the sessions as a percussionist. “He was hiding in there! He jumped out and started dancing. George had to shut the session down and kick him out. ‘Hare Krishna!’ ‘Fuck off.’”

“We’d be playing, and here come all these Hare Krishna guys, bouncing in, slinging out flower petals and giving out peanut-butter cookies,” Whitlock told me. “We were recording! I thought these guys were fairies, with their bald heads and paint and shit. George had a whole shitload of ’em, living out at Friar Park. They were all camped out in some kind of commune. They were everywhere.” Whitlock was born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee; this kind of Eastern mysticism was probably never going to be quite his thing. “Peanut-butter cookies out their ass, I ain’t kiddin’ you,” he said.

When the Krishna devotees either quietened down or left altogether, the sessions proceeded in a spirit of easy participation and co-operation, as Peter Frampton later recalled. “Everyone was there because they were great players,” he said, “and when you get a bunch of great players, you don’t say, ‘I want you to play it like this.’ You just say, ‘Here’s the song, what can you bring to it?’ The only thing George ever said was, ‘That was a good one’, or ‘Let’s try it again.’ No-one was left out, no-one was treated as a session musician… He was sort of ego-less – which was strange, because he was a Beatle. Or maybe that’s why.”

All Things Must Pass was released in November 1970. Its cover, taken in the grounds of Friar Park by the American photographer Barry Feinstein, was a monochrome shot of a glum-looking George surrounded by four gnomes: a pretty obvious reference to The Beatles, whose break-up was by then heading towards the High Court. The album went to No.1 in the UK, US, and beyond; though My Sweet Lord would eventually snare its author in a legal action based on its resemblance to the Chiffons’ 1963 hit He’s So Fine, its incarnation as a global hit single only confirmed a huge sense of triumph.

Everything flowered again, moreover, when George persuaded a gaggle of star names – including Ringo, Dylan, and Clapton, who was by then struggling with heroin addiction – to appear with him at Madison Square Garden in August 1971, in aid of the famine-hit country of Bangladesh. He took to the stage in a white suit, and played a set that included not just While My Guitar Gently Weeps and Something, but Wah-Wah, Beware Of Darkness, and the inevitable My Sweet Lord.

In retrospect, there was a sense of all this having being enough. The follow-up to All Things Must Pass, the comparatively understated Living In The Material World, didn’t appear until the summer of 1973, and George’s solo career never again achieved the wonders he had managed three years before. Those 28 songs remain his definitive artistic statement, capturing not just love, loss and spiritual wonderment, but The Beatles’ split and its immediate aftermath.

Many of the people from this chapter of the post-Beatles story – Delaney Bramlett, Carl Radle, three-quarters of Badfinger, and George himself – are no longer here. But All Things Must Pass endures: a monumental piece of great art, on which The Quiet Beatle suddenly roared.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #222. The 50th anniversary editions of All Things Must Pass are out now.