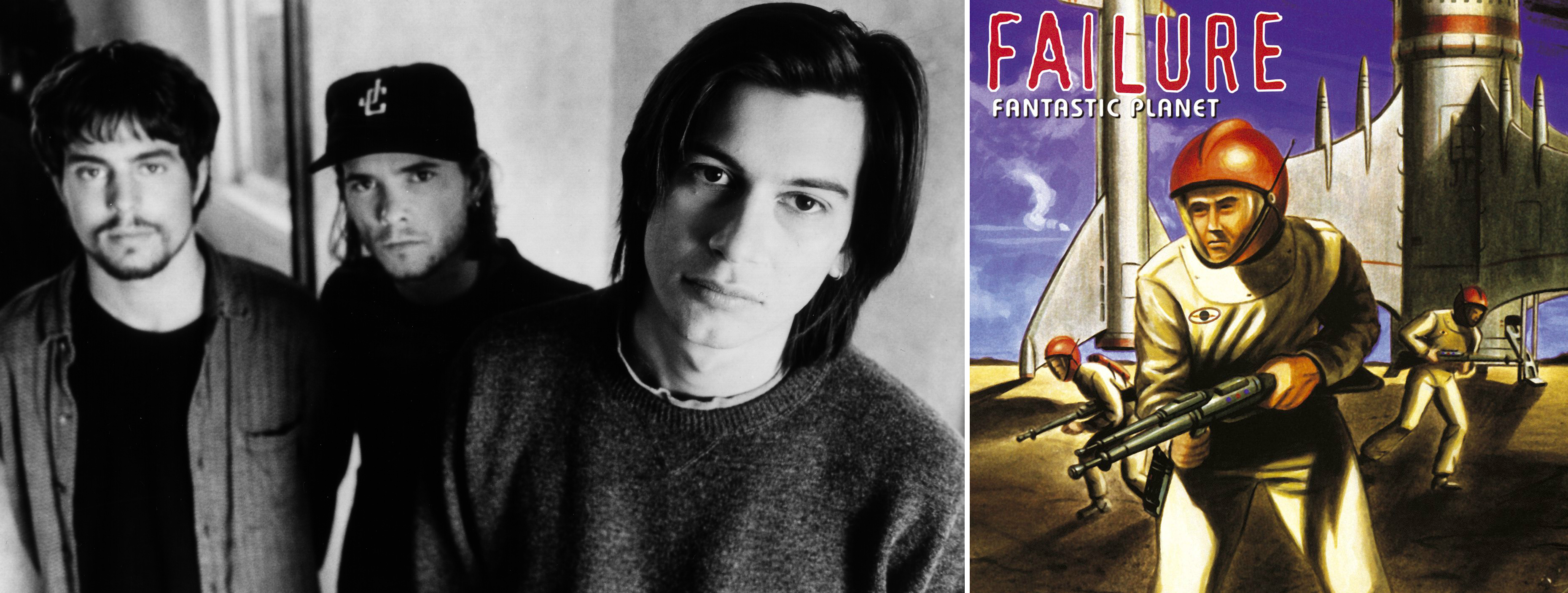

Failure's Fantastic Planet: An Oral History

The story of the trio's classic 1996 release, as told by the band themselves...

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

19 years ago this month, Los Angeles alt-rock trio Failure released ‘Fantastic Planet’.

Named after René Laloux’s stop-motion sci-fi film, their third studio album was equally epic in scope and ambition. With a running time of almost 68 minutes, the seeds of their self-produced 17-track effort were sewn in a rented house in Tujunga, just outside of Los Angeles – owned by Lita Ford, no less.

As the trio neared completion of the album, they were informed that their label was up for sale and would gather dust on a shelf for 18 months. Fantastic Planet almost fell through the cracks until Warner Brothers released it in August 1996.

While Fantastic Planet failed to trouble the Billboard Top 200 album chart upon its release, the band’s following perversely grew in the years following their split in 1997. Tool, Paramore, Cave In and Deftones have all cited the Los Angeles-based trio as an influence and this collection is regarded by many as their masterpiece.

Failure reunited in 2014 and recently released their fourth album, The Heart Is A Monster. TeamRock caught up with the band – Ken Andrews, Greg Edwards and Kellii Scott – to learn about the creation of this cult classic…

Greg Edwards (multi-instrumentalist/vocals): “Our last album, Magnified didn’t really fit anywhere. It was a pretty quirky record for that time. It was eclectic and it wasn’t grunge, which was happening right then.”

Ken Andrews (vocals/guitar/bass/engineer): “That was a big problem then. We weren’t strictly a grunge band. We were heavy in certain aspects, but we had a lot of other stuff going on, like an exploration of dissonance and counterpoint. We were initially signed before grunge hit. Slash [the record label] signed us after seeing us play live, because we had no recordings.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Greg: “Our heaviness came from early Helmet and classic rock, like Led Zeppelin. Stuff like that. Grunge exploded between Comfort and Magnified, so we just did what we wanted to do. Going into Fantastic Planet, I think we just wanted to make an epic record. I think Magnified gave us a lot of confidence in terms of our ability to write interesting pop songs and still have a cinematic sensibility. I think we wanted to expand on that and maybe make a record which would hit people right off the bat.”

Ken: “I didn’t have the vision of such a sprawling record when we went in to record that Fantastic Planet. I wanted to make something brave and up the ante, and all that, but I have to give credit to Greg for wanting to put basically every song we did up there on the record, and in that sequence.”

Greg: “We rented a rehearsal space in this big blue building in California. I remember we got the recording equipment and that was the very beginning of do-it-yourself recording. I mean, we were one of the first bands to take that on ourselves completely, because Ken was such a proficient engineer. We used these ADAT machines and I think Pitiful was the first song idea we worked on.”

Ken: “We also had Sergeant Politeness and Daylight already, from being on the road.”

Greg: “Yeah, we had early versions of those. Somewhere in that period, I wrote this little acoustic song, The Nurse Who Loved Me at my parents’ house, up in the guest room. I had like a DX7 and just an acoustic guitar going into a little cassette four-track. The line ‘She acts just like a nurse with all the other guys’ and the whole thing came together really quick.”

Ken: “I had a similar thing with Saturday Savior. I had just got that Telecaster for $400 at the Guitar Center, went home and set it up with my tuner, Rat pedal and Fender Twin in my apartment. I’d bought a bunch of heroin and smoked some and sat down and played. We recorded a demo of that song at the rehearsal space so we wouldn’t waste time experimenting when we moved to the house to do the album.”

Greg: “At the rehearsal space, we’d record hours of us jamming. We’d go through the recording and find the good moments and make a tape and expand those ideas. I remember Paul D’Amour [Tool’s original bassist] did this in Replicants. He brought his H3000, Eventide H3000, which you know, is like a classic studio unit with great effects and weird pitch effects and delay effects. He brought that and left it there, and that’s how Heliotropic came about – that weird harmonised sound.”

Kellii Scott (drums): “I remember being very unsatisfied by everything I played during those sessions. I remember on Smoking Umbrellas, I was playing this really busy tom-snare thing. It just felt I was falling short of what I was trying to do. I was going out on a limb but learned how to hone things in, throw stuff away and make things more functional and simple. It drove me insane. I felt like a complete failure during those cassette sessions – I was very worried.”

Ken: “But we ended up pulling a lot of those ideas from the sessions.”

Kellii: “The Another Space Song beat was the one cool thing that I did. It was unlike anything I’d ever done in my life.”

Greg: “With the guitar parts? I remember. We had a strong foundation of very rough ideas going in.”

Ken: “Just nuggets, you know? We’d literally have eight bars of something which would sync up for a minute. Then we’d have to listen to it, analyse it and re-learn what we were playing and make it into a song. There were rarely any vocals, but we repeated that on the new album.”

Greg: “We were living in that house, so we’d be recording stuff and you’d go into your own bedroom, shut the door and take a nap. When you’d wake up from the nap, a lyric might come to you and you’d go back down the hall and inject it into the process. It was really fluid that way.”

Ken: “If you went to your room, sometimes the music would still be going. But from down the hall, you’d get this other level of objectivity and another way of looking at a problem. You could come back in a few hours later and be like, ‘I got it, I know what we should do in the bridge…’”

Kellii: “Some songs, though, like Solaris, for instance, were worked from the ground up in the studio. I mean, there was nothing in that song that existed before we were there.”

Greg: “It’s really common now for people to record in their houses now, but back then it wasn’t that usual.”

Ken: ”For rock bands at the time, the accepted way was: you wrote your songs, you would demo them and then the producer was hired, and selected, and scheduled. The producer would listen to your demos, make a bunch of notes, then you would go into rehearsal space with your producer and he would shape the songs and then you would go into the recording studio. Going into the actual recording studio was more of an exercise in getting good performances in high-fidelity recording.”

Greg: “It’s all the magic of the moment when you’re recording a demo and you don’t give a shit about the sounds. You can’t re-create that and that’s why demos often have the magic. Stanley Kubrick, for instance, didn’t do rehearsals; he would just keep going with takes until people were insane or forgot what they were even doing – then something interesting would happen.”

Kellii: “That’s exactly how we did the drums! I was like their drum machine… ‘Now we do this, now we do that, let’s change the arrangement, forget everything we’ve been doing for four hours…’ It was insane and I’ve never been so exhausted.”

Ken: ”The label actually wanted to release the Magnified demos instead of the finished album. They thought they were more interesting and had more life. But we always had intended them to be just a reference point for a real drummer to play, so, that was frustrating. So when it came time to do Fantastic Planet it was like, let’s just do the demos with our drummer, and that’s the record. That’s it, you know. No separate rehearsal, no going in to the real studio. The first time we do it, it’s for keeps.”

Ken: “There were a lot of creative battles, in terms of how I wanted to do things on Fantastic Planet. The drug problem wasn’t quite a problem yet, but it was definitely seeping in – in terms of the material and the content. The drugs? Mostly heroin and pot.”

Greg: “Before the heroin really took over for me, I’d wake up, make a bunch of coffee and drink a lot of Bailey’s Irish Cream. That went on for a period of time. Bailey’s Irish Cream and marijuana. Then heroin kind of came up underneath that and took over.”

Ken: “We were focussed in the way that we knew our whole existence was on the line because the first two records hadn’t broke through and sold. I felt some pressure there, for sure, so we were all in it together and the only real conflicts were creative ones.”

Greg: “Just tiny details.”

Ken: “We sweat the details in this band.”

Greg: “I felt we’d made something really substantial, you know? I remember driving around near the house and listening to a rough mix of Another Space Song and thinking that alone was what I’d wanted to do with music my whole life.”

Ken: “My creative satisfaction with the record was palatable, but it was unfortunately cut extremely short by the news that the album we were turning into the label wasn’t going to be put out because they were trying to sell themselves. We never overcame that. The whole problem was part of the downward spiral of the band, really. It came out a year and a half after we released it. It was beyond frustrating. Greg went off at the deep end with drugs and I was just beside myself with frustration and depression.”

Kellii: “We didn’t think this album was ever coming out.”

Ken: “Warner Brothers were the distributor for Slash Records, who we were signed to. They got a hold of the record about a year after we had finished it and the head of A&R and the current president loved it. But then, we had to wait another six months [because of contracts]. That was a nightmare, really.”

Greg: “I wasn’t feeling much of anything by the time it was released.”

Ken: “It was anti-climactic. I felt like the band was slipping away from me. We still managed to get some decent tours and did Lollapalooza in 1997. After that, my last attempt to keep the band together was to try and have some writing sessions with Greg because Warner Brothers wanted us to make another record. The writing sessions never happened and I called it off at that point.”

Kellii: “When [Ken] called and told me I was like, ‘OK,’ you know? I never stopped for a moment to think about the depths of like what just happened.”

Ken: “It was bad, it was bad. I don’t think anyone wanted it to end. It was just kind of a survival thing at that point and it was a really, really hard decision, very painful. That’s why this feeling of redemption [following their reunion and new album, The Heart Is A Monster] is quite strong.”

Greg: “When we completed Fantastic Planet, I think we had created something special. I think that just kind of felt like the music resonated with people and continued to do so over the years. There was never a time when Failure just disappeared off my radar. We were kind of like revolving around this central planet of gravity that was bringing us back to eventually working together again.”

Failure’s new album, The Heart Is A Monster is out now. For more information on the band, visit their official site. Want to read more? Check out this feature below.

Born in 1976 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Simon Young has been a music journalist for over twenty-six years. His fanzine, Hit A Guy With Glasses, enjoyed a one-issue run before he secured a job at Kerrang! in 1999. His writing has also appeared in Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, and Planet Rock. His first book, So Much For The 30 Year Plan: Therapy? — The Authorised Biography is available via Jawbone Press.