“I was unusually nervous… You may be doing exactly the same set, but it can have a completely different vibe.” When David Gilmour revisited Pompeii and faced the ghosts of Pink Floyd

Safer pyrotechnics, local hero status and the benefit of a Wallace & Gromit movie helped make his 2017 concert movie a very different experience from Floyd’s 1972 release

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

In 2017 David Gilmour released Live At Pompeii, a movie that documented his return to the scene of Pink Floyd’s 1970s triumph the previous year. In a conversation with Matt Everett, he reflected on the experience of returning to a place full of ghosts.

David Gilmour has long been known to conclude a tour with a flourish, be it playing in the middle of the lagoon in front of St Mark’s Square in Venice with Pink Floyd in 1989, or at the historic shipyards of Gdansk in 2006. However, in 2016, he surpassed himself by bringing his show to a place firmly etched in world history, and Floyd history: the amphitheatre in Pompeii, the site buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

In 1971, of course, his old group, under the direction of Adrian Maben, shot their legendary Live At Pompeii film, which captured them playing in the amphitheatre, empty, save for the crew and a few local kids. In 2016, it couldn’t have been more different – Gilmour brought his entire touring operation along to perform a spectacular show in front of a paying audience. It was to be a time when ghosts were laid to rest.

Gilmour first had the idea of returning to Pompeii in 2015 as he was touring Europe and then South America. “I don’t get out on tour very often and I like to create a special occasion for people, so it’s nice to play in beautiful old places that have a special vibe to them,” he says. “We started at Pula in Croatia in an absolutely spectacular amphitheatre, a place I’d never been to before. We continued that idea all over Europe. In these beautiful places. There’s a whole added element of specialness that the building gives to it. Hopefully the audience will remember it forever.”

Playing venues such as this is not without enormous logistical issues. “Luckily I don’t get to hear about most of them,” he laughs. Production manager Roger Searle and lighting man Marc Brickman scope each location out,months in advance. “Roger is brilliant and completely unflappable,” Gilmour reveals. “He gets everything done and if you ask him to do something, he always says ‘yes,’ never ‘no’. We need people like him.”

The South American leg of the Rattle That Lock tour was a key experience for Gilmour. The continent has a reputation for audience intensity and complex logistics, with tales of missing payments and concert cancellations. “Through all those years of our Pink Floyd touring, no one ever managed to convince us it was worth going through all that, so we never did,” the guitarist says.

“But times have changed and things are now far more professional. We were playing to up to 50,000 people a night, which for me as a solo artist was quite a surprise, but the audiences are so fantastically enthusiastic, polite and welcoming. There’s a more even split between men and women, which is refreshing. Many people had told me over the years how great the South American audiences are and I would go, ‘Yeah, sure – it’s just the same as everywhere else really.’ But they were right. It really was a treat.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The Rattle That Lock tour lent itself to extraordinary venues and, as it progressed, it seemed to lead to one in particular. “I don’t want to get completely stuck only in amphitheatres, but someone suggested we try for Pompeii again. The minute the idea was mooted I said, ‘Go for it. Absolutely.’ I said, ‘We’ll never get it.’ I didn’t think they’d allow it.

“So we sent our trusty team off to negotiate with the town of Pompeii. It turned out that the mayor and the townspeople were thrilled with the idea and were very keen to expedite it. They all made it work fantastically well.”

Playing the venue was a huge statement. Although Gilmour did not watch the fabled 1972 film again, he was aware that by revisiting, and adding an audience, it would become a full-blown spectacle. “The statement element came along a little bit later. I don’t think we originally were that concerned – it was just one of a number of places we were playing. We thought, ‘We did okay with it back in ’71 without an audience – maybe it would be fun to do the DVD there.’ We recorded and filmed shows all over the world, but we thought this one would be something extra special, which indeed it was. The two shows went really well.”

We thought, “It’ll be just like Wallace & Gromit when the rocket takes off and all the mice put their sunglasses on!”

The Avis trucks that had trundled round back in 1971 were replaced with fleets of equipment, all of which had to be wheeled carefully down aged paths so as not to damage the legendary structure. “All of that had to be negotiated,” Gilmour says. “Things like the fireworks and pyro are designed to look exciting and haphazard. You want it to look dangerous, but it’s very carefully controlled and our people know exactly what they’re doing. It’s a highly professional system, and so no damage was done to the site. You have to convince people that you are that sort of organisation.

“We’ve been through that in the 70s. That stuff was, in fact, highly dangerous in those days. Health and safety didn’t exist, pretty much, and there were a lot of very shaky moments on major tours. But these days it’s very slick.”

The spectacular concerts in July 2016 obviously opened doors in the minds of the media to a Pink Floyd reunion again, but Gilmour wasn’t concerned. “You can’t worry about the media – they’re going to find something to obsess about. The story of ‘will we, won’t we’ comes up time and time again, and it will never go away, I suspect, however convincing I try to make the argument.”

For Gilmour, walking back into that amphitheatre after a gap of 45 years was unforgettable. “It brought back all sorts of memories of the time we had there, and the Heath Robinson sort of setup. We had a Brenell 8-track tape machine sitting at the back and hundreds of little wires and a little mixing desk. It’s amazing we got anything as good sound-wise out of it as we did, doing take after take in the blazing sun. There are a lot of memories and ghosts in that place.”

Adrian Maben was there, as well as historian Mary Beard. “Entirely coincidentally, Adrian was there with an exhibition of photos from 1971. It was not connected to our visit. It was booked to be there anyway. We had talked about getting someone there to talk about the place itself. Mary was mentioned. It turned out that she was coming to the concert anyway. Things serendipitously just fell into place. Mary paints it as rather more prosaic than our idea of what it might have been like. Somehow that makes it feel even more real and more alive than watching Spartacus or something. The audience would have been sitting there with no beers, no refreshments and no loos.”

As the original performance and film has had an indelible impact on a whole generation, Gilmour had to go through the modern-day duties of meeting local dignitaries, being whisked off into the modern town and given the freedom of the city by the mayor. “There are a number of people there who had been kids when we did the 1971 show, who had managed to wheedle their way into the amphitheatre to watch. They said what a significant memory in their childhood that was, and for me to come back was such a thrill and a treat for them.”

The strict capacity limit in the amphitheatre gave the show a special resonance, one that translates well to the film. “I was unusually nervous, but we got to the end of the first night and thought we’d cracked it. It was really good; and the second night was even better. You may be doing exactly the same set, but it can have a completely different vibe. It’s one of those weird, magical things when you really don’t know what you’re going to get.”

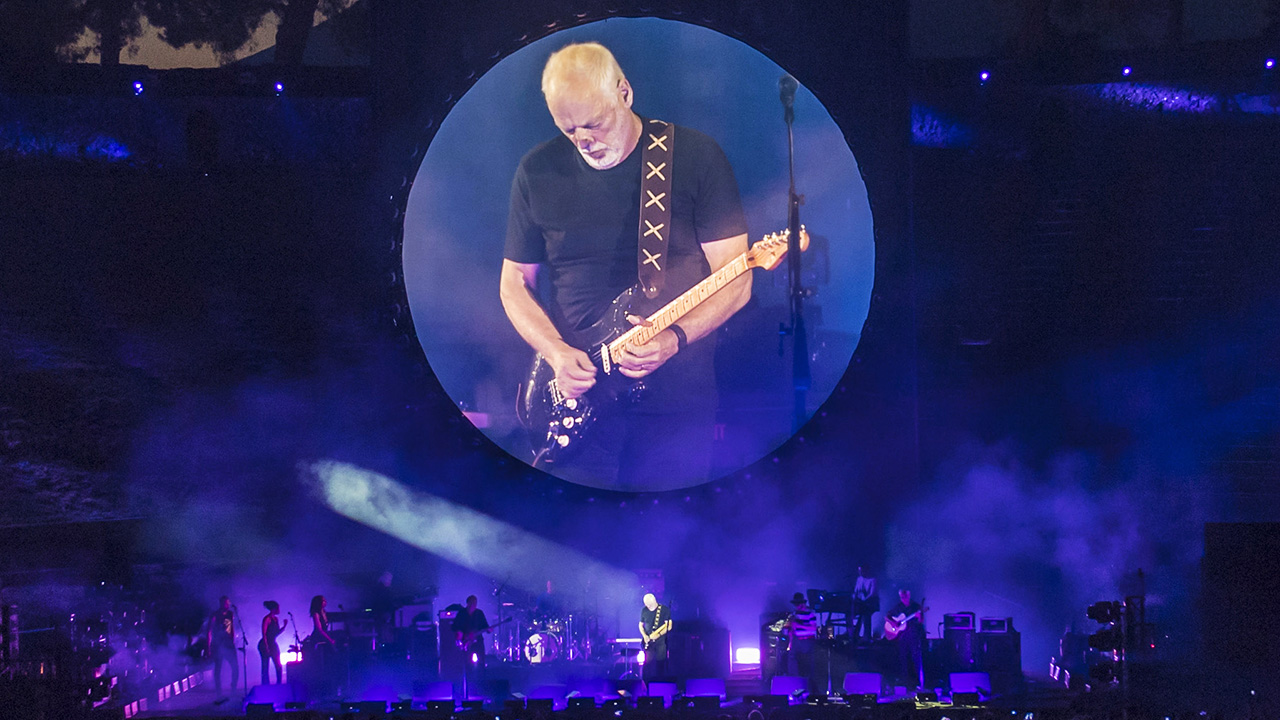

The show – as anyone who caught the tour would testify – was outstanding: the balance of new and old, of supporting players and the star wrapped in a major league son et lumière. “Putting it all together and fitting everything into that venue was a challenge for Marc Brickman. We had drones filming from about a mile away and you see a tiny little circle in the distance with light and smoke sort of pouring out and pulsing. It’s spectacular, and beautifully shot.”

Of course, being a Gilmour show, there are some bombastic moments. “I haven’t managed to grow out of those yet!” he laughs. “I keep thinking that bombast is a thing of the past, but it still sneaks back in.” One such moment is when the band don sunglasses during Run Like Hell. But as with a great deal of Gilmour’s work, it’s borne out of practicality.

I’m dying to watch and hear it in a cinem… the sound and the occasion, having a lot of people together enjoying that moment

“There are the strobes that Marc is using at that moment and you actually cannot see a thing. With the flashing, it makes your brain do strange things and it’s easy to forget where you are. Someone wanted to wear sunglasses and we thought, ‘Yeah, let’s get everyone to do it and it’ll be just like Wallace & Gromit when the rocket takes off to go to the moon and all the mice put their sunglasses on!”

With a show in two halves that builds to a climactic finish, Gilmour added The Great Gig In The Sky to the set for Pompeii. “And of course, we did One Of These Days, which we hadn’t been playing on the tour. That’s the only song that we played there back in 1971.”

Pompeii is a place of ghosts, and it would have been impossible for Gilmour not to be touched by their presence. “There are songs that Rick Wright wrote [The Great Gig In The Sky], and there’s A Boat Lies Waiting, which is about Rick, for which I wrote the music and Polly [Samson, Gilmour’s wife] wrote the words, which we put into a sequence.

“Wish You Were Here always reminds me of Syd when we play it. And in a place like Pompeii, those things are heightened because of the time we spent there all those years ago, and because of the special occasion. These things all come on to you while you’re performing and hopefully heighten the emotion of the occasion for the audience as well.”

Gilmour had around six shows before Pompeii to break in his new touring band, which he introduced after the first leg of the tour, with only himself, bassist Guy Pratt and vocalist Lucita Jules remaining constant. The group gelled well.

“There are a number of songs that have moments for improvisation. I get to do most of it, of course, but Chuck [Leavell], Greg [Phillinganes], João [Mello] and Chester [Kamen] are the new people on this leg of the tour and they all get their moments to stretch out.

“I’m into perfection in a way, but at the same time, I don’t want the songs played perfectly as on the record. I want it to be live music. I want people who play with me to have some autonomy to be able to change something that suits them and suits the mood of the moment. And, of course, if that goes wrong, we discuss it afterwards! But I would rather that we go for something and enjoy actually playing, rather than holding them tight to a format.”

One of the highlights of the tour was the sax playing of young Brazilian Mello, who handled Dick Parry’s legendary parts with great elan. “He’s a beautiful player, really good. He had his 21st birthday when we were in Brazil, playing in his home town, and it’s kind of special to think of all the different ages playing in a band and feeling like you are part of something together.”

He thoroughly enjoyed shooting the film, and it shows. It’s directed by Gavin Elder, who helmed the capture of his 2006 show in Gdansk.“It looks fantastic,” Gilmour enthuses. “I’m dying to go in and watch and hear it in a cinema, with those big bass speakers that make sound travel through a room in a way that speakers in a small room don’t quite have the wavelength for. It’s very special.

“I’ll be sitting there in September watching it in that proper way for the first time myself. A cinema release is the best way of putting it out there – the sound and the occasion, having a lot of people together enjoying that moment. I can’t wait.”

So with the magic of Pompeii captured on film, what’s next for David Gilmour? He’s stated that he won’t tour without new music, and as we know, that takes him a while to make. “There are several songs that are close to being complete that didn’t make it onto this album for one reason or another. You never know what you’re going to do until you start; and when you do, you find that something you absolutely loved before doesn’t fit quite into what you’re trying to do now.

“You just have to wait and see what comes up. It took 10 years last time. I’m really hoping, without making any promises, that it won’t take 10 years this time, but that I will get back in soon and start working again. Then, following that, I’ll be out again.”

And will Gilmour ever return to Pompeii? “Of course. Most of the places I played I’d go back to. Verona is such a lovely place, we played both times in 2015 and 2016; Orange; Pula; and the great places in America. We did a couple of nights at the Hollywood Bowl – it has a magic to it. Marc Brickman did some new films to project. Usually we project onto the circular screen but you can project film onto the whole of the inside of the Hollywood Bowl’s dome.

“The Chicago Auditorium is a beautiful old theatre that I’d played with Pink Floyd in the early 70s. I had a half-memory of doing it. You think, ‘God, oh I hope I was right, it wasn’t just a fantasy.’ Thankfully, it truly is a beautiful venue. Radio City Music Hall in New York, which we’d also played with Pink Floyd, is one of those special places. Madison Square Garden is always a favourite. It has a great sound and a great atmosphere.”

So, David Gilmour: Live At Pompeii claims Gilmour’s share of his old group’s legacy in the way that Roger Waters did with his live show of his portion, The Wall, several years earlier. However, ironically, the performance, in such heightened nostalgic surroundings, serves to underline the greatness of Gilmour’s music now, more than merely being frozen in time.

With the concert, film, the DVD and audio, does David Gilmour think, in a way, that doing Pompeii again was a nice way of drawing a line under that one part of his legacy?

“Let’s hope so!” he says.

Daryl Easlea has contributed to Prog since its first edition, and has written cover features on Pink Floyd, Genesis, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel and Gentle Giant. After 20 years in music retail, when Daryl worked full-time at Record Collector, his broad tastes and knowledge led to him being deemed a ‘generalist.’ DJ, compere, and consultant to record companies, his books explore prog, populist African-American music and pop eccentrics. Currently writing Whatever Happened To Slade?, Daryl broadcasts Easlea Like A Sunday Morning on Ship Full Of Bombs, can be seen on Channel 5 talking about pop and hosts the M Means Music podcast.