“It wasn’t pure hatred all the time”: Pink Floyd’s The Wall movie and its feuds, falling-outs and friction

Bob Geldof ruthlessly baited Roger Waters, Gerald Scarfe feared he’d created a new skinhead movement and the media hated the morbidity – but the third part of the multimedia trilogy was a triumph

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Appalled by the behaviour of Pink Floyd’s audiences, in 1977 Roger Waters hit upon the idea of building a wall between them and the group. By the end of 1982 The Wall had become a multi-platinum album, a groundbreaking live show and an acclaimed film. In 2019 Prog revisited the making of the movie.

The final part of Roger Waters’ The Wall trilogy was the 1982 film. It followed the notoriously difficult creation of the album and its subsequent tour – but the movie production was where the wheels really fell off the juggernaut.

Although David Gilmour looked after the musical side of things, Waters and Gerald Scarfe had a key vision they wanted to see through. More shows were arranged in 1981 for the film’s director, Alan Parker, to shoot, but it became clear it would be unworkable. A dramatised version incorporating Scarfe’s animations was the alternative course to take.

Waters himself screen-tested for the lead role of Pink, but, as Parker said later, he was “closer to Albert Speer than to Albert Finney”. The director had someone else in his sights to play Pink: Bob Geldof. He was of course aware of Pink Floyd; but not a fan.

“I bought See Emily Play and Arnold Layne when I was a kid,” he recalled. “They were fantastic pop records. Then I heard The Piper At the Gates Of Dawn. I thought it was very unconvincing. ‘Piss-poor At The Gates Of Yawn,’ we called it. ‘I’ve got a bike, you can ride it if you like’ – now I think it’s a fantastic thing, but back then I just thought, ‘Fey English nonsense.’ The Floyd, liquid gel and all that. My association with all that was people around my area who I thought were twats. I was a mod, for fuck’s sake, not some platypus-collared, flowery-shirted faux-hippie!”

But Parker was very much out to get him. A fabled argument in the back of a cab between Geldof and his manager, Fachtna O’Kelly, resulted in the singer railing against both the Floyd and the film. Unbeknown to him – and unbelievably – the cab driver was Waters’ elder brother, John. Geldof was summoned to meet Waters.

“It was in some restaurant,” Geldof recalls. “You know if you meet a hero, you’re very intimated; you gabble or you’re silent. I wasn’t, because they weren’t really my guys, like, say, the Stones. He was pleasant enough, but he wasn’t all ‘hail fellow well met;’ he was quite chippy. We went back to his beautiful house and played snooker. I kept winning, much to his annoyance. We kept playing until he won a game.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“He asked me at one time to write something about the meeting at the restaurant. I remember his opening gambit: ‘I really like I Don’t Like Mondays.’ He said: ‘There’s some great ideas in there. You should have extended them out into a longer form.’ I replied: ‘Thank you very much. The Wall is a really good album. Maybe you should have reduced it to a three-minute single.’

“He says he didn’t say it, so the piece didn’t appear anywhere. I think we’re

quite like each other – y’know, chippy, smart-arsey, a bit of ego in there – just a little bit, obviously. And of course he’s annoyingly a tad more successful. What a songwriter, though. We’re friends, which I like.”

Intrigued by the process of film-making, Geldof eventually signed on, and shooting of The Wall began at Pinewood Studios in September 1981. Twenty minutes of Scarfe’s animation would be used. “Parker was always very laudatory about my work,” Scarfe says. “He was quoted as saying that the reason he wanted to make the film was because of my flower sequence.”

But fissures opened up almost at once, with Waters and Scarfe on one side, and Alan Parker and producer Alan Marshall on the other. There would be several hissy fits, all in the name of the art. Parker encouraged Waters to take a six-week holiday. Meanwhile it became clear that more music would be required, so Geldof recorded a new version of In The Flesh, teasing James Guthrie and Gilmour with a cod-Irish accent every time they went for a take.

They were cutting the hammers into their hair and having it tattooed onto their arms. I thought: ‘Shit, have I started a new movement?’

Gerald Scarfe

But he immersed himself in the role. His blankness and wild, staring eyes took Pink into his numb, alienated existence. He remembers one scene with tremendous affection: when he throws a TV out the window in One Of My Turns. “I went to Parker, ‘Listen, if I throw the telly out the window and it doesn’t break, can I keep it?’ He said I could. So I put two mattresses underneath the window. It looks like a skyscraper, but it’s only a few feet off the ground. If you look at the scene, you see me chucking it out the window very gingerly. So it lands on the mattresses, and I still have that Sony Trinitron at home in Kent.”

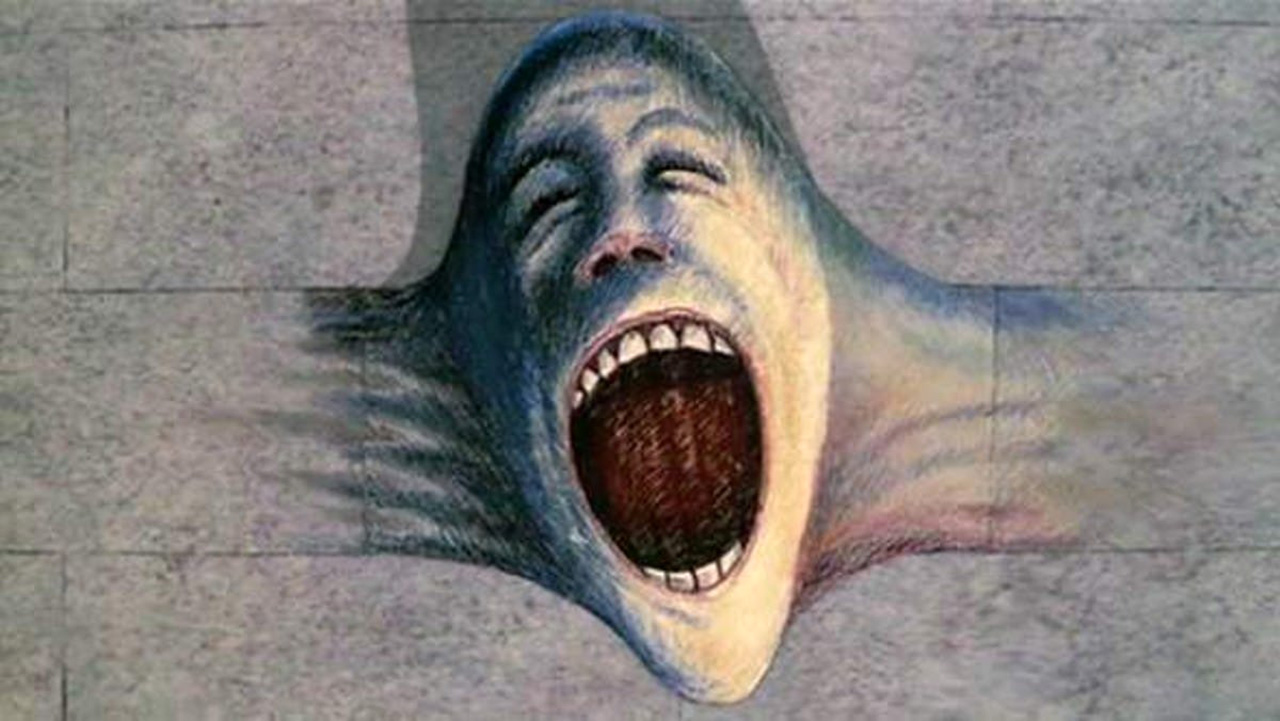

One of the classic scenes in the film is the fascist rally, featuring extras in the form of infamous Essex skinheads the Tilbury Trojans. “I worried about the skinheads,” Scarfe says. “They were cutting the hammers into their hair and having it tattooed onto their arms. I thought: ‘Shit, have I started a new movement?’”

Some of the most amazing sections are when his illustrations are brought to life, such as the armchair and the battlefield. “I called it the alien landscape,” he recalls. “It used to amuse me when people working on the film would say, ‘Where’s Bob gone?’ ‘Oh, he’s gone up the alien landscape.’ This thing that had been in my mind was suddenly a real place.”

He adds: “There was a lot of bonhomie. It wasn’t pure hatred all the time. We got on because we were working on the same bloody project. You can’t keep walking off every time someone shouts at you.”

At the end of production the props were sold off. Waters and Scarfe went to the sale. “I have got Bob’s lamps from the room he went crazy in,” Scarfe says. Parts of The Wall – along with Geldof’s Sony Trinitron – are kept in houses in the south of England.

Pink Floyd – The Wall debuted at Cannes on May 23 1982. It premiered in the UK on July 14 at London’s Empire Theatre with, in aid of Nordoff Robbins and attended by the band, Geldof, Pete Townshend, Andy Summers and Superman Christopher Reeve, among others. When it opened In LA, instead of seeing the film, Geldof and Waters went off and played pool.

Record Business said of the production: “Roger Waters’ view of mankind is totally and morbidly hopeless.” But it made respectable money. The VHS home video boom carried it through Christmas that year, and it quickly became a student favourite.

Initially, there was talk of a soundtrack album, but there was hardly a great deal of material. However, when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands in April 1982, and Margaret Thatcher responded by sending a task force to the South Atlantic, Waters suddenly had subject matter – and so the soundtrack mutated into The Final Cut.

It’s a great band despite everything. They’re just too good not to make an astonishing record

Bob Geldof

The Wall lives on. The most poignant version was the Waters’ concert in Berlin seven months after the Berlin Wall came down in 1990. “I was so very impressed with Roger Waters’ speed in putting it on so soon after,” said flautist James Galway, one the many stellar guests who took part. “It was rather like doing Wagner’s Ring with only one rehearsal!”

In the 00s Waters took the show on the road again. It had become a far wider- reaching spectacle, looking at the desire – as he told the BBC – “to break down the walls between ethnicities, religions, nationalities.” In 2011, for one night only, Gilmour stood atop that wall again, at London’s O2 Arena, singing Comfortably Numb and playing that spinetingling solo. Nick Mason joined him and Waters in the rubble at the end.

The Wall remains immovable object : an ambitious piece with a compelling backstory of feuds, falling-outs and friction; memorable songs, spoken-word passages that have passed into the lingua-franca of men of a certain age; and, in Comfortably Numb, Pink Floyd’s definitive anthem.

“Roger’s a great songwriter, as is Dave,” Geldof says. “Much as they may argue about the content of the record, and who did what, it’s just one of those things. It’s a great band despite everything. They’re just too good not to make an astonishing record.”

Roger is not very dictatorial. He was always a brilliant person to work with for an artist

Gerald Scarfe

Scarfe is delighted that Waters keeps forging ahead, playing the very stadiums that had once so revulsed him. “Last time I saw him, he said: ‘Well, what’s not to like? I’m playing to thousands of people all the time.’ I’m certainly glad I worked on The Wall. I am mostly known for working with Pink Floyd, because they are universal.”

The three fronts of The Wall – the album, the tour and the movie – are testament to Waters’ collaborative process. Could he have made it without the rest of Floyd? “Not this album,” producer Bob Ezrin says. “And he couldn’t have made it without me or James [Guthrie, engineer], either.

“Everyone’s personality and ideas adorned the work, and the band’s distinctive sound and style permeated the whole piece, even in places where we introduced other players, orchestras, choruses and, yes, schoolkids. Everybody got out on that ledge together during the recording and took risks.”

“Roger is not very dictatorial,” Scarfe states. “He was always a brilliant person to work with for an artist. He was very easy to get on with in that way.”

“It was a privilege, a joy, sometimes a real challenge to work on The Wall with them,” Ezrin adds, “and the result remains remarkably relevant today.”

The last word goes – perhaps surprisingly – to James Galway, who said after he’d played with Waters in Berlin: “Every musician should know The Wall. If they don’t, they should be ashamed of themselves. It’s one of the greatest things written in rock.”

Daryl Easlea has contributed to Prog since its first edition, and has written cover features on Pink Floyd, Genesis, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel and Gentle Giant. After 20 years in music retail, when Daryl worked full-time at Record Collector, his broad tastes and knowledge led to him being deemed a ‘generalist.’ DJ, compere, and consultant to record companies, his books explore prog, populist African-American music and pop eccentrics. Currently writing Whatever Happened To Slade?, Daryl broadcasts Easlea Like A Sunday Morning on Ship Full Of Bombs, can be seen on Channel 5 talking about pop and hosts the M Means Music podcast.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Pink Floyd - The Wall Movie - The Trial [4k AI Upscale and Restoration] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/w0zBKIneldI/maxresdefault.jpg)