"I couldn't believe how casual she was acting. Did she not realise how insane this was?" The story of the 15-year-old boy who flew to Rio to see Ozzy Osbourne

Stephen Rea's 40-year friendship with the Osbourne family began at Rock In Rio in 1985 - and he tells the story in a new book

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

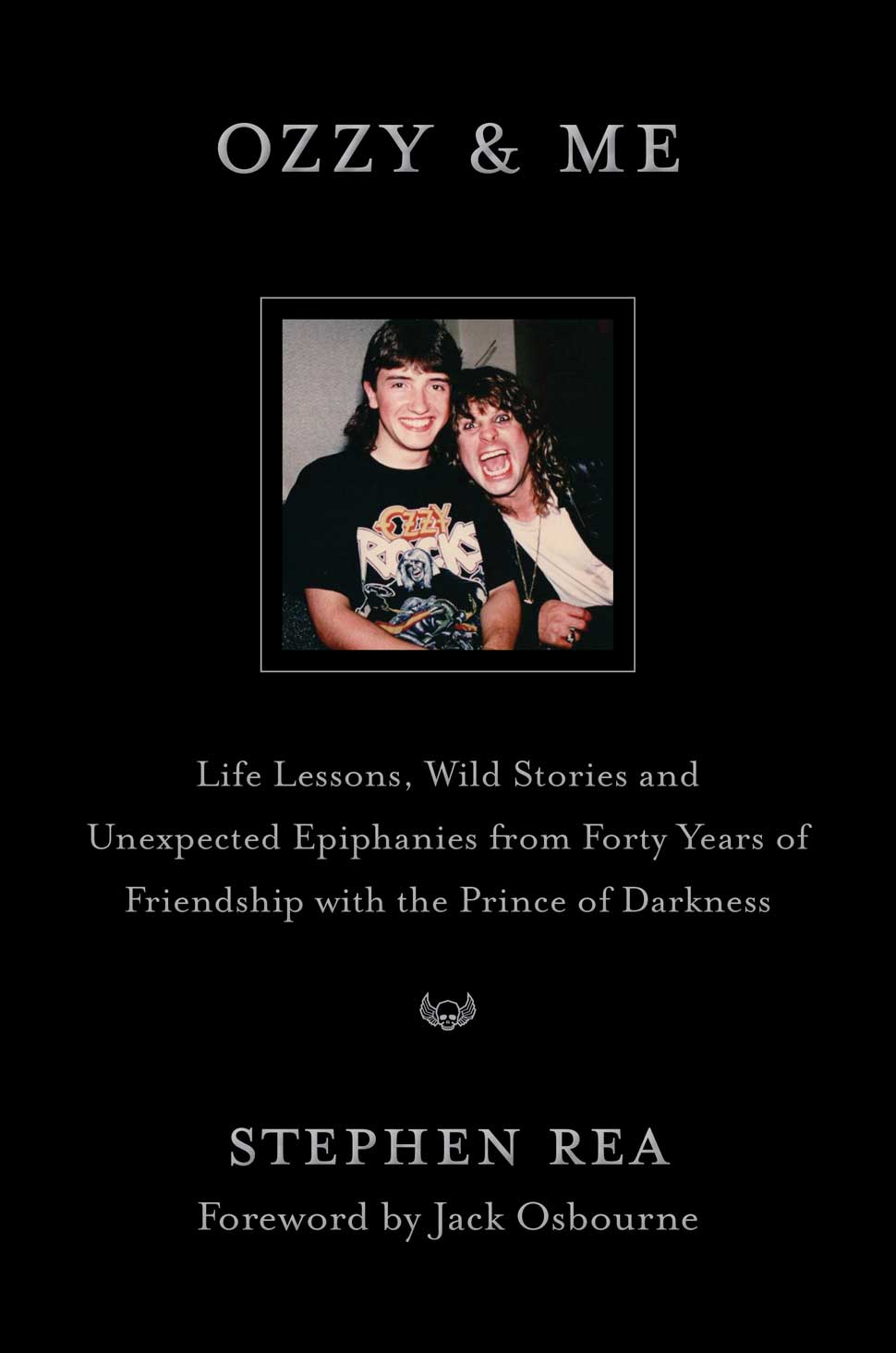

Stephen Rea's book, Ozzy & Me: Life Lessons, Wild Stories and Unexpected Epiphanies from Forty Years of Friendship with the Prince of Darkness, tells the story of a teenage boy from war-torn Belfast who reached out to Ozzy Osbourne and became a lifelong friend of the singer and his family, from Rock In Rio to Back To The Beginning and beyond.

In the excerpt below, Rea reveals how a muttered remark was the beginning of his miraculous journey.

At 6pm on Thursday, November 1, 1984, the local news played on a ten-inch portable black-and-white TV in our tiny kitchen. More death and destruction in dark, depressing Northern Ireland.

I was four weeks away from turning fifteen and sat on a hard, wobbly wooden bench at our worn, soft-pine table in my school uniform of black sweater, white shirt, black tie, and black trousers, my black-stockinged feet slick on the torn, muted-beige laminate floor. I was inhaling the usual dinner of fish sticks, fries, peas, and buttered bread. Head down, mouth full, I attacked issue 80 of Kerrang! Page three had a photo of Ozzy’s surprise appearance at a recent Iron Maiden gig, and alongside it a breakout box read:

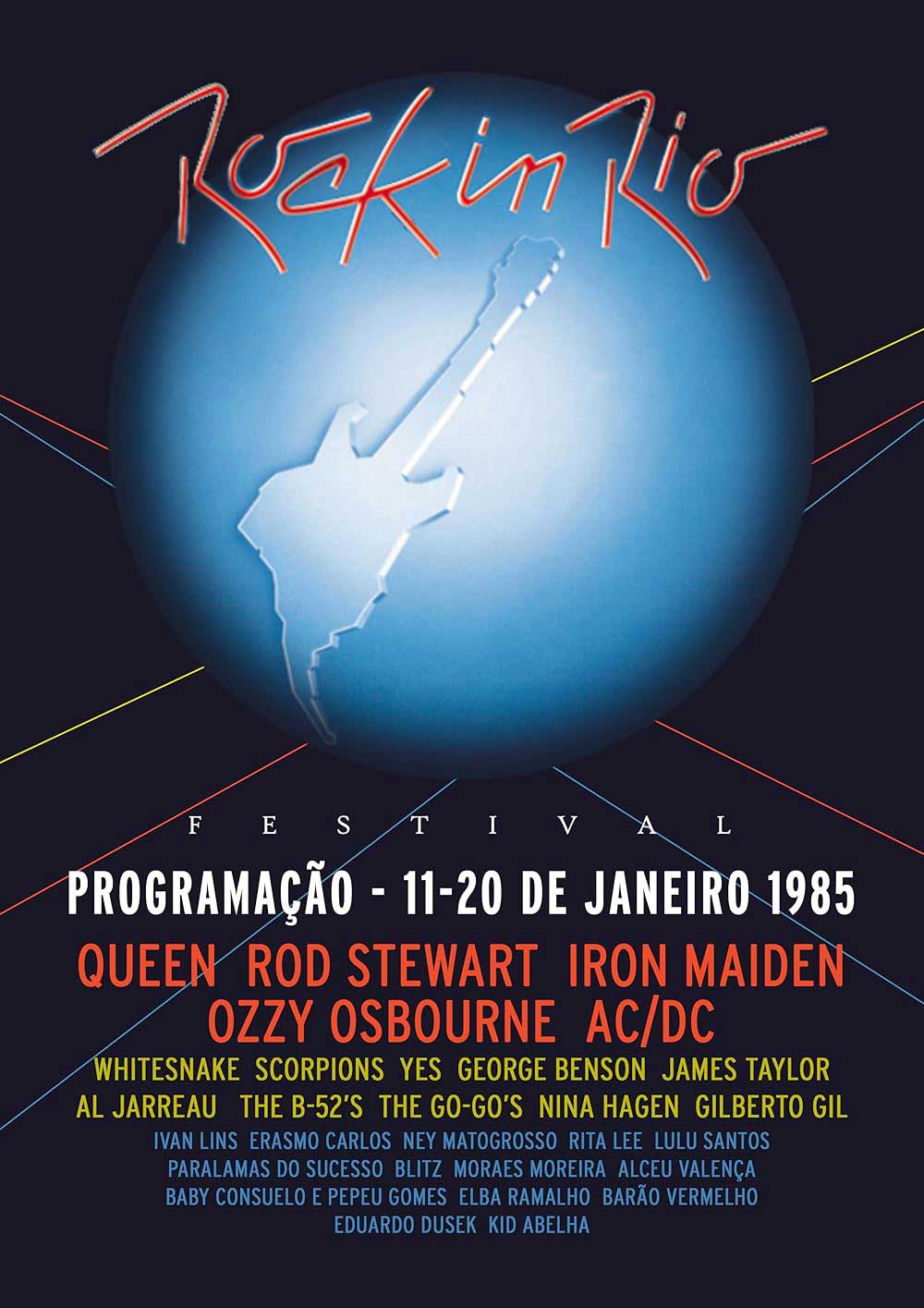

A major ten-day rock festival is to take place in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) between January 11–20 next year. Altogether, 13 international acts will appear alongside an equal number of Brazilian artists. Among the top names already confirmed to perform are Queen, Rod Stewart, Def Leppard, George Benson, James Taylor, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Nina Hagen, the B-52’s, the Go-Gos, Al Jarreau, Ozzy Osbourne, and the Scorpions.

I muttered, more to myself than anyone else, “Ozzy is playing a big festival in Rio.”

My dad, his attention on the screen, sipping heavily sugared tea, turned away just long enough to say, “Find out about it. I’ve always wanted to go to Brazil.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

My parents weren’t wealthy, but they believed in enjoying what money they earned and valued experiences over possessions. When my dad was 19, he and a pal tried to hitchhike to see our local amateur soccer club Linfield play in Portugal. They turned around a few days in. Their progress was slow, and they weren’t going to make the game. But that experience helped instil in him a love of travel, a love my mom shared.

When I was only a few months old, they took me to Majorca in the Balearic Islands, then a run-down backwater ruled by fascist dictator General Franco. They saved all year for our summer vacation: while most Brits went to the Mediterranean, in 1980 and 1981 we flew to Florida, though in 1982 we went to Spain for the soccer World Cup.

Nonetheless, not for a nanosecond did I think I would end up six thousand miles away in Rio. I figured my dad was joking, so I laughed it off and returned to my fish sticks and magazine.

He wasn’t joking. His shop was next door to a travel agency. He asked if they knew about Rock in Rio. They rummaged in their files and found a four-page leaflet – a half-assed sliver of a brochure from a London tour operator.

On the front and back were the most uninspired photos ever used to advertise one of the planet’s most exciting cities: a beach, a palm tree, a lily pond, those souvenir bottles containing scenes made from coloured sand. It listed the daily lineup and had a brief description of a thirteen-night tour costing £895 per person (about £3,600, or $4,700, in 2024).

It also featured the whimsical caveat: “The price does not include surcharges arising from unavoidable increases in costs due to Government action.” As Latin American specialists, they’d seen new administrations seize power and lobby a tourist tax. With connecting flights from Belfast and spending money, it would cost more than $15,000 today.

My mum wrote to the fan club looking for more details, mentioning my early membership status. The following Thursday, I arrived home from playing soccer. “Ozzy Osbourne’s secretary called,” my mum said nonchalantly.

Technically, it was Sharon’s assistant, Lynn. She had worked for Sharon for a year, and one of her many jobs was overseeing the fan club. No doubt she was permanently swamped, and answering mothers of teenage fans was low on her priorities. She could have ignored it or sent back a form letter referring us to a travel agency. Instead, she got our number from information and rang.

My mum had scribbled notes on the back of a torn envelope: the days Ozzy was playing, the hotel they were staying at, their arrival date.

“Lynn told me not to buy tickets to the concert,” she said like they were old friends. “If we make it to Rio, they’ll get us in for free. She gave me her number and said you should call her. She wants to speak to you herself.”

I couldn’t believe how casual she was acting. Did she not realise how insane this was? I wasn’t really going to fly to South America to see Ozzy, right? I went to bed bewildered and lay awake for hours.

Lynn and I were in constant contact that November and December. She regularly checked in on our trip planning, every conversation elongated by barrages of interruptions as her other line rang nonstop, her putting me on hold while she dealt with the important stuff she was getting paid for.

We connected instantly. I had no idea why she was so patient with me – I guess it was her genuine personality: warm, helpful. She was a twentysomething English secretary who had worked in the music business since leaving school, while I was a fifteen-year-old Irish youngster, but we chatted easily.

The first time we spoke, she told me about an embarrassing incident when Rod Stewart approached her table in a pub, adding, “Not even Ozzy and Sharon know that story!”

Right from the off, though, I knew my school, Campbell College, would be a problem. The festival was January 11 to 20, in the heart of the academic year. Unless they agreed to give me two weeks off, I couldn’t go. It was a traditional all-boys British boarding school (though it also had day students like me), an institution superglued to its history, where our exams were set by Oxford and Cambridge.

We wore a cap and shorts until we were thirteen – even in snow and sleet – and when an adult entered the classroom, we stood. At recess, the candy store was staffed by the principal’s wife, and the most you were allowed to spend was fifteen pence. We queued to wait our turn, and if she heard a noise – a whisper, a laugh, anything – she slammed the hatch closed, and it stayed shut until there was absolute silence.

The worst part was the six-day week. We had classes every Saturday. It was enriching and challenging, but occasionally like living in a Dickens novel, antiquated and conservative beyond belief. And not the type of educational establishment to grant students an extended absence to attend an Ozzy Osbourne gig. I begged my mum to write another letter, and I delivered it to the headmaster’s Victorian study, pleading the case I’d rehearsed eighty times.

He kept me waiting until the following week, when I came home and spotted an envelope on the floor, underneath the telephone seat, where it nestled after being aggressively projectiled through the letter box by our mailman. I picked it up, took a second to rub a thumb over the school crest embossed into the crisp white envelope, blew out my cheeks, and opened it.

There was a preamble about the request being most unsatisfactory... highly irregular... not wanting to set a precedent... but he had consulted with my housemaster, who described me as “pure gold,” and added, “A trip to Brazil has to have some academic value.”

Finally, the crucial sentence I can still recite: “I acquiesce, under protest, and ask that it does not happen again.”

The reason I recall it is because I didn’t know what “acquiesce” meant. I dived into my schoolbag and riffled through my dog-eared pocket dictionary. Elated, I couldn’t wait to tell my parents in person, and rang them at work.

It was on.

Excerpted from Ozzy & Me: Life Lessons, Wild Stories and Unexpected Epiphanies from Forty Years of Friendship with the Prince of Darkness by Stephen Rea, foreword by Jack Osbourne. Copyright © 2025 by Stephen Rea. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Not to be confused with the Hollywood actor of the same name, Stephen Rea is a former UK newspaper journalist and the author of three books: Finn McCool’s Football Club, World Cup Fever and Ozzy & Me. He also wrote a chapter in the official Ozzy Osbourne biography Diary Of A Madman, and contributed to the anthology Airplane Reading. He lives in New Orleans, where he teaches writing classes, both in person and online.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.