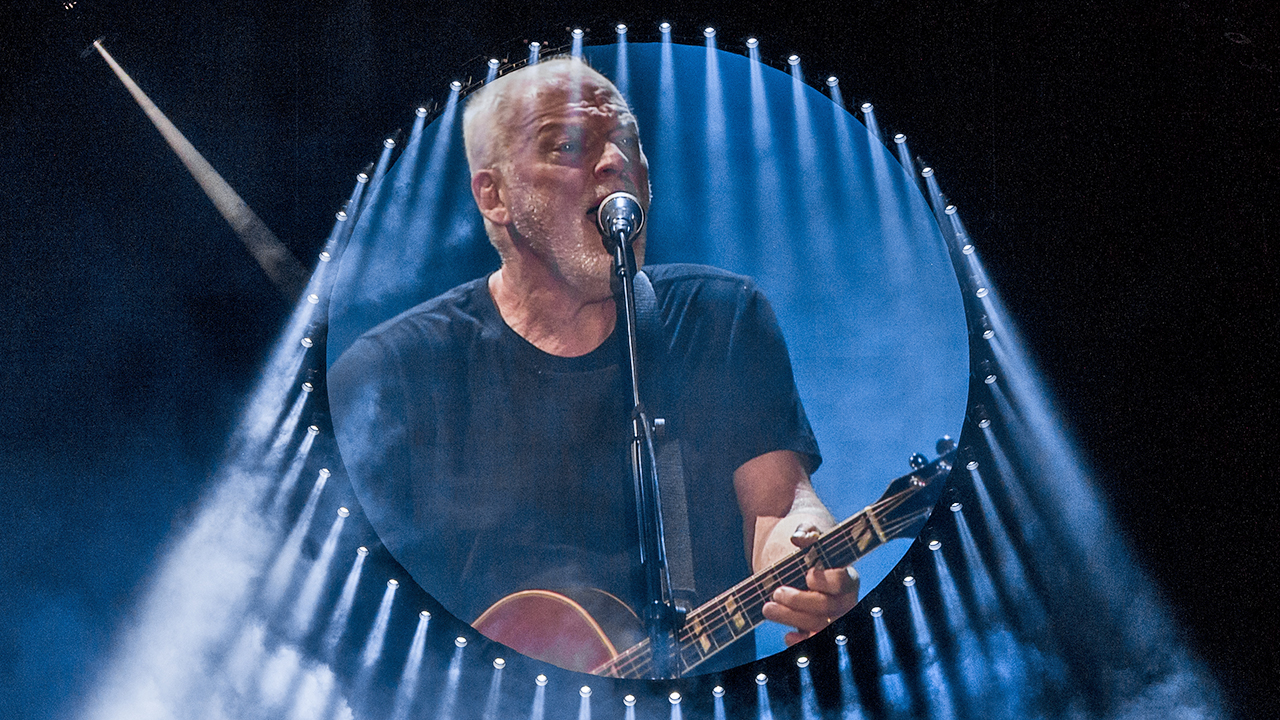

“I was about to sign the form when the recruiting inspector asked a question”: Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson was once seconds away from becoming a cop instead of a prog star

He expected to live at least three other lives. But subculture signposts led him to a career as a band leader who never made enemies – and a brief period as Tony Iommi’s boss

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

In a wide-ranging interview with Prog in 2015, Ian Anderson reflected on the three careers he’d expected rather than musician, the subculture experiences that led him to prog, and what kind of band leader he’d been since Jethro Tull formed in 1967.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Did you ever experience an epiphany – a moment that made you go want to be a musician?

It was more of a slow burn, starting as a four-year-old hitting a few notes on the piano to appease my ageing grandmother. If there was a tipping point it was Elvis Presley singing Heartbreak Hotel, but also skiffle in the form of Lonnie Donegan.

The key message with skiffle was: “You can do this.” Any 11-year-old could strum half a chord on a beat-up acoustic – so we did.

But at that point I still wanted to be an engine driver. Later I wanted to be a policeman.

You’d have made a good copper. How close did you get?

I was 17 and about to sign my name on the form when the recruiting inspector said, “Sorry, forgot to ask, do you have any O levels?” When I told him I had eight, he told me to come back when I’d been to university, and he’d get me a really good job in the police. I felt rejected, yes; but it was good pragmatic advice.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Like Pete Townshend and Syd Barrett, you’re a product of the post-war art school system.

I thought I’d have this cul-de-sac career as an art teacher in a boys’ school somewhere in rural England. When I was 18 there was this growing subculture of blues, thanks to John Mayall and Eric Clapton.

Then there was Sgt Pepper and The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn in ’67. These were all signposts that maybe there was something in this for us.

You grew your hair, wore tight trousers, and apparently your father worried that you might be homosexual.

My father did go through a period where, unfortunately, he referred to me as… [deep sigh] a “jessie” an old Scottish term that didn’t quite define you as homosexual, just “girlie.” But it was all in his mind.

I grew up in that magic 10-year period that saw the emancipation of planet Earth – a respect for freedoms, equality for black Americans and a growing awareness that women shouldn’t just be baby-making housewife machines.

I’d much rather hear anyone singing in their own voice. Otherwise I’ll assume you’re fake

Unlike some of your peers, you’ve always sung in a British accent, though.

I lived and breathed black American blues, but I’d not done those stereotypical things I thought black American bluesmen did – picking cotton or working on a chain gang. It didn’t seem sensible to me to follow in the footsteps of some lower, middle-class white boy by trying to sing like a black American.

You must have tried it at least once though?

I supposed I did when I first tried to imitate those songs. I heard Mick Jagger, though, and that put me off. It’s the same with Elton John – I think, “Why are you singing in that stupid voice?” I don’t think it’s insulting; just a bit wet. Amy Winehouse would have been twice the person she was if she’d sung in something resembling her own voice.

This is clearly a bit of a bugbear for you.

It’s just plain silly. I’d much rather hear anyone singing in their own voice. Look how we loved Ian Dury and Alex Harvey. Otherwise I’ll assume you’re fake.

Throughout your career you’ve always been out of step with your contemporaries. Was there any sex and drugs on the road with Jethro Tull?

No. But it wasn’t because of any morality, it was because I was shit scared of catching some awful disease. I also didn’t want to risk my addictive personality by smoking anything stronger than cigarettes.

I’m not one of those people who could smoke a couple of cigarettes a day. I was smoking as many as I could afford. So I thought I’d better control that before I got involved with everyone passing around the standard soggy joint… which I thought was a bit like licking the handle of a gents toilet. Why would you want to do that?

Martin Barre had a fight with a dressing room chair once, which caused me no end of joy

There have been so many people through Jethro Tull since 1968. Have you made many enemies?

I haven’t made enemies, but some have made enemies of each other. There are people who still don’t talk to each other and I’m a bit miffed about that. It began with Mick Abrahams and Glenn Cornick. Right from the get-go, there was a problem. It got nasty. Not in fisticuffs, but physical threats.

Has there even been a Jethro Tull punch-up?

Martin Barre had a fight with a dressing room chair once, which caused me no end of joy, because Martin so rarely lost his temper. But luckily he chose to attack a chair rather than me or another band member.

Is the popular image of Jethro Tull as a “blokes’ band” inaccurate?

Our audience tended to be more boy/girl. But it can be slightly more male-oriented in certain cities. It also wasn’t unusual to see people of Indian and Pakistani origin and black Americans at our shows. Jethro Tull also found fans in Latin America and Asia.

Why do you think that is?

It’s a good by-product of the broad influences I had as a writer. I’ve always had an interest in other music, even when sung in a language I couldn’t understand. I drew from it all – whether it was Charlie Parker and bebop or some exotic Indian classical music.

If Tony Iommi did learn anything, it was that if you’re supposed to be there at 10am for a rehearsal, then be there

Tony Iommi played with Jethro Tull briefly in 1968, and said he was shocked by your work ethic, and tried to get Black Sabbath to be more disciplined.

Tony was never exactly a member of Jethro Tull. We were just mutually exploring the possibility of doing something together. But, yes, if there was anything Tony did learn it was that if you’re supposed to be there at 10am for a rehearsal, then be there.

Are you a tough bandleader then?

Probably a bit of a pain in the arse. But I’ve always been a stickler for punctuality. I’m not the archetypal pop person who fits the romantic ideal of the louche, laid-back character who just drifts in and out of things. Life’s too short. I like to get the job done and I enjoy finishing on time.

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.