“Flying model planes and covering the phone with a pillow was all I was capable of at the time”: The unexpected triumph of Mike Oldfield’s Hergest Ridge, an album he didn’t want to make

Overwhelmed by the success of Tubular Bells, he found peace in a solitary house on a hill and in playing ancient music in an old mansion. Even when his peace was shattered, he managed to create an uplifting and chart-topping record

In 1974, Mike Oldfield topped the UK chart with Hergest Ridge, the ambitious follow-up to his unexpectedly successful debut Tubular Bells. It was an album the overwhelmed 21-year-old struggled to make – and yet he delivered a work with astonishing uplifting energy.

How do you follow up one of the most innovative debut albums of all time? That was the challenge a young Mike Oldfield found himself facing in 1973. The debut in question, the now-iconic Tubular Bells, had been released that May via Richard Branson’s fledgling Virgin Records to widespread critical acclaim – and no small amount of commercial success.

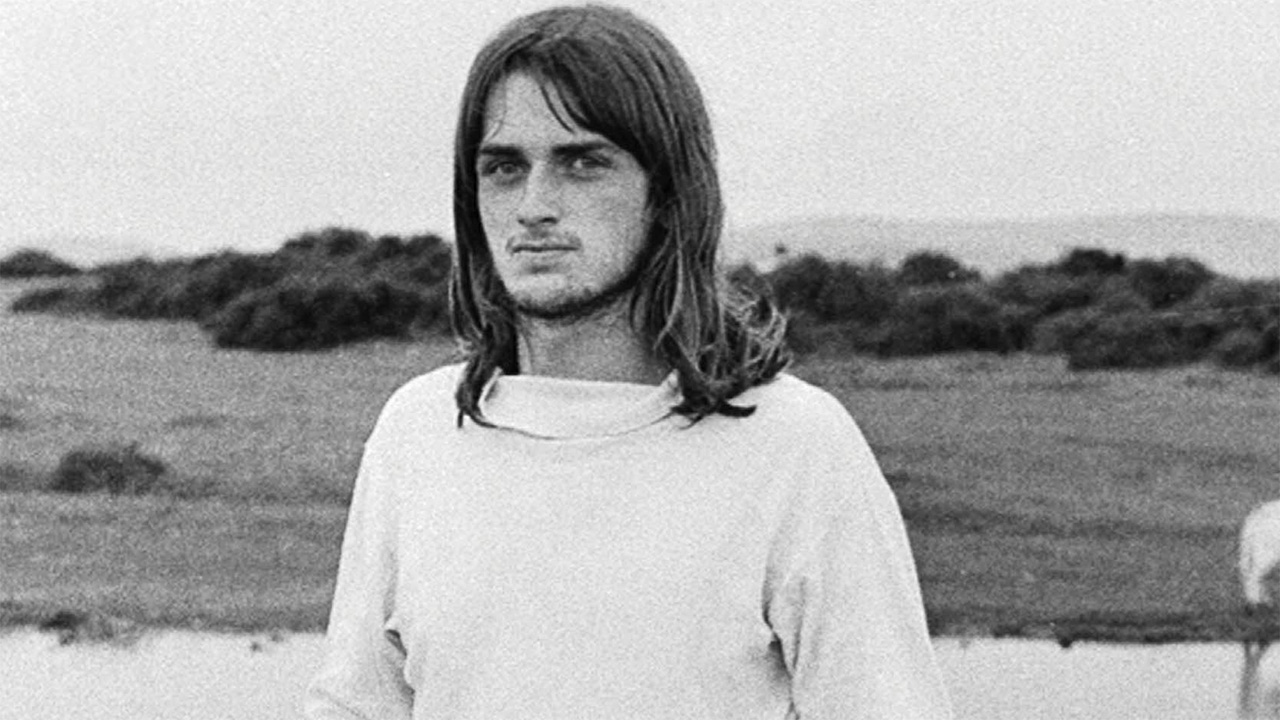

Oldfield had channelled oceans of hard work and angst into his music, and he desperately needed a rest. He took a drive in his reconditioned Bentley across the Severn Bridge, ending up in the small market town of Kington, Herefordshire, where he spotted an isolated house for sale on Bradnor Hill, with magnificent views across the Brecon Beacons. Without even viewing the property, he bought it.

"He’d seen it from afar,” recalls Mike’s sister, singer Sally Oldfield, “when he was driving down to Hereford, trying to escape all the press. It turned out to be a very rickety affair with no heating.”

His new home, named The Beacon, was to play a crucial role in the development of his next album, Hergest Ridge. Sally explains: “Tubular Bells was composed over a period of years. Mike said, ‘I was holding on to my sanity.’ Music was his escape from the mental anguish of having to take care of our mother during most of his adolescence.”

The siblings’ mother Maureen suffered greatly from mental health problems. Composer Terry, Mike’s older brother, recalls: “He wrote me a letter that said, ‘I may be able to find somewhere peaceful to live away from the world.’ That was The Beacon.”

Oldfield had his sanctuary – but his peace proved short-lived. “Richard Branson wanted a new album ASAP,” says Sally. “It was a terrible pressure for Mike, forced to do something immediately. But he did start to cobble things together.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

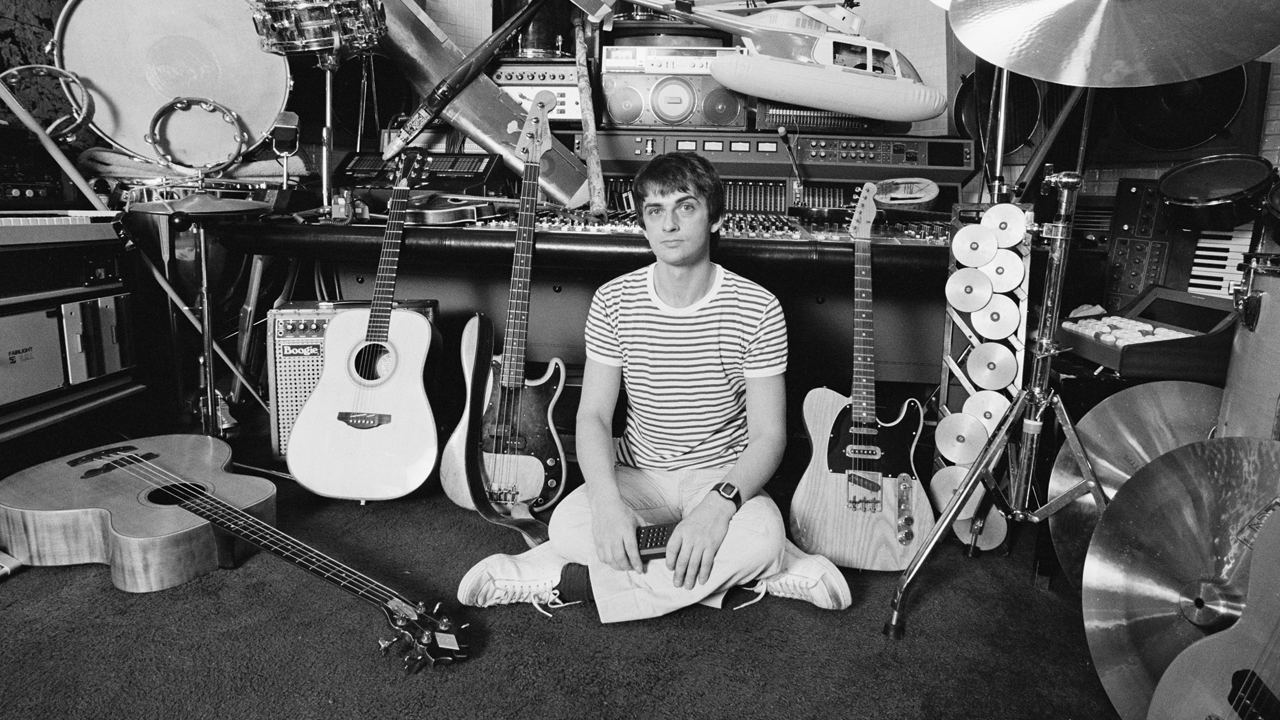

Terry adds: “One day I visited Mike at The Beacon. In the basement he’d covered all the walls and ceilings with egg boxes for sound insulation. He was doing a demo for Hergest, cross-legged on the floor with a four-track TEAC recorder, mixing onto a stereo TEAC.

“In his mind he was still the guy doing Tubular Bells – he wasn’t the guy who could ring Richard any time he liked and say, ‘Can you bring me a 24-track mixing console, please?’ He didn’t realise he could do that. He didn’t realise he was successful.”

As Mike himself states in his liner notes for the new edition: “I just wasn’t prepared for that level of attention and the sense of importance that was suddenly attached to me. People wrote about me as if I knew the answer to it all. I was 21 and trying to find my feet, let alone an answer.”

Initial progress was hampered by an unexpected event: American film director William Friedkin was working on The Exorcist and wanted music from Tubular Bells for the soundtrack. “The timing was quite critical,” remembers Sally, “because Mike was in the throes of composing Hergest. He got this amazing news about the Hollywood movie and all the pressure that came with it – ‘You’ve got to tour the States; America wants you.’”

In his 2007 autobiography Changeling, Oldfield recalled: “All I was interested in was flying my model aeroplanes on Hergest Ridge and covering the telephone with a pillow. It was all I was capable of at the time.”

But the respite he’d hoped for was being chipped away. “When he first moved in,” says Terry, “he was luxuriating in the peace and quiet. But as soon as everybody knew where it was, the press found him, and Richard would send someone down to talk to him. He really didn’t have that peace. I wonder if he ever found it.”

He had no introduction to the music at all, yet he played as somebody who understood it fully. His thinking takes place in notes rather than words

Les Penning

Oldfield did make friends in the area, though. Among them was musician Les Penning, who would turn out to be a big influence, and who’d also fallen in love with the landscape. “I’d just moved from Oxfordshire and bought a water mill on spec, 10 minutes from Kington,” Penning recalls. “It was extraordinary – high hedges, banks, roads that had been rutted by carts over millennia.”

A passionate devotee of early and medieval music, he soon made connections and appeared at a local attraction. “I cobbled together a small quartet and we ended up playing at Penrhos Court – not for money, just for the joy of doing it.” A group of Grade II-listed buildings dating to the 13th century, it had been bought by entrepreneur Martin Griffiths in 1971 and converted into a hotel and restaurant.

“We were playing 18th-century dance tunes and much earlier stuff,” says Penning. “One day Martin said, ‘I think there’s room for somebody else to join you. I know somebody who lives up the hill who plays guitar; maybe you should give him a call.’”

Penning admits: “I’d never heard of Tubular Bells – it just simply wasn’t in my world. But I gave Mike a call and he said, ‘Come up and bring an instrument.’ So I went up to The Beacon, this very nice house overlooking a vast area of Herefordshire. I took out my recorder and we played.

“Then he wanted to show me what he was doing, so he pulled out a single, which was a bit of Tubular Bells on one side and Froggy Went A-Courting on the other, which I really, really liked.”

The safest I’d ever felt was sitting in front of the fireplace, playing medieval tunes with my strange recorder-player friend

Mike Oldfield

Soon Oldfield started playing with Penning’s group. In Changeling he wrote: “The safest I’d ever felt was sitting in front of the fireplace at Penrhos Court, having drunk most of a bottle of wine, playing these simple, undemanding medieval tunes with my strange recorder-player friend.”

Penning recalls: “It was a marvellous thing. He had no introduction to this sort of music at all, and yet he played it as somebody who understood it fully. I had loads of curious instruments, and when he came to dinner he’d pick one up and start playing. I think he’s done that from time immemorial. He has this tremendous facility – his thinking takes place in notes rather than words.”Impromptu gigs at Penrhos continued for months and influenced Oldfield’s work from then on. “There are dance tunes on Ommadawn which are straight out of 1640,” Penning says.

Work on Hergest Ridge proceeded as, bit by bit, Oldfield built up his studio at The Beacon. “He had this Farfisa organ with matchsticks stuck between the keys to keep them playing, up and down the keyboard,” Penning recalls. “It was absolutely fascinating.”

Sally and Terry both contributed to the new music. “He invited me down to sing on it in the summer,” says Sally. “It was always lovely working with Mike, because he’s just so into his world. He knows exactly what he wants and he’s a very good communicator. Once you’re in there and doing a session with him, all the angst goes out of the window; he’s just focused on what he loves to do.”

Other musicians drifted in and out. Clodagh Simonds – singer with prog-folk band Mellow Candle – and arranger/composer David Bedford were both visitors to The Beacon, as were June Whiting and Lindsay Cooper on oboe, Ted Hobart on trumpet and the Trinidadian drummer Chili Charles. Demos were finally complete by February 1974, and engineer Tom Newman, who’d worked on Tubular Bells, returned to help sculpt the finished product.

He wasn’t ready to do another album. He wasn’t in the right frame of mind

Tom Newman

Sessions were held during February and March 1974, first at Basing Street Studios, London, then at Chipping Norton Studios. Oldfield found both locations oppressive, and those sessions were abandoned. Instead work took place at The Manor, with mixing at AIR Studios in London. “Michael really wasn’t ready to do another album,” Newman recalled in a 1997 interview. “He didn’t want to do a follow-up; he wasn’t in the right frame of mind for it.”

Released on August 30, 1974, Hergest Ridge was even more complex and nuanced than its predecessor. It delivers a bucolic, pastoral feel, almost classically composed in two parts, illustrating Oldfield’s astonishing ability to move fluidly from one idea to another, with sumptuous guitar playing to the fore. There are wilder moments, such as the crashing sheets of sound halfway through Part Two, but what shines through the meticulous music is a warm, bright haze of emotion.

Critical reception was mixed. Nevertheless, Hergest Ridge reached No.1 in the UK charts, reamining there for three weeks until it was displaced by none other than Tubular Bells. “I thought it was a wonderfully peaceful album,” reflects Sally. “Very soothing. There’s a magic in Mike’s music – I remember how stressed he was at the time, but he was still able to create something spiritually uplifting.”

Oldfield wrote: “Hergest Ridge was a real struggle to begin with, but having pushed myself to get started, it was like piling twigs on a fire. It took on a life of its own.”

Somehow, he’d once again transmuted struggles and stresses into an album that’s stood the test of time. The newly-released 50th anniversary edition breathes new life into old magic. To quote its creator again, from his new liner notes, it’s an album composed “with the breathtaking scenery and the changing seasons as my inspiration.”

Chris Wheatley is an author and writer based in Oxford, UK. You can find his writing in Prog magazine, Vintage Rock, Longreads, What Culture, Songlines, Loudwire, London Jazz News and many other websites and publications. He has too many records, too many guitars, and not enough cats.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.