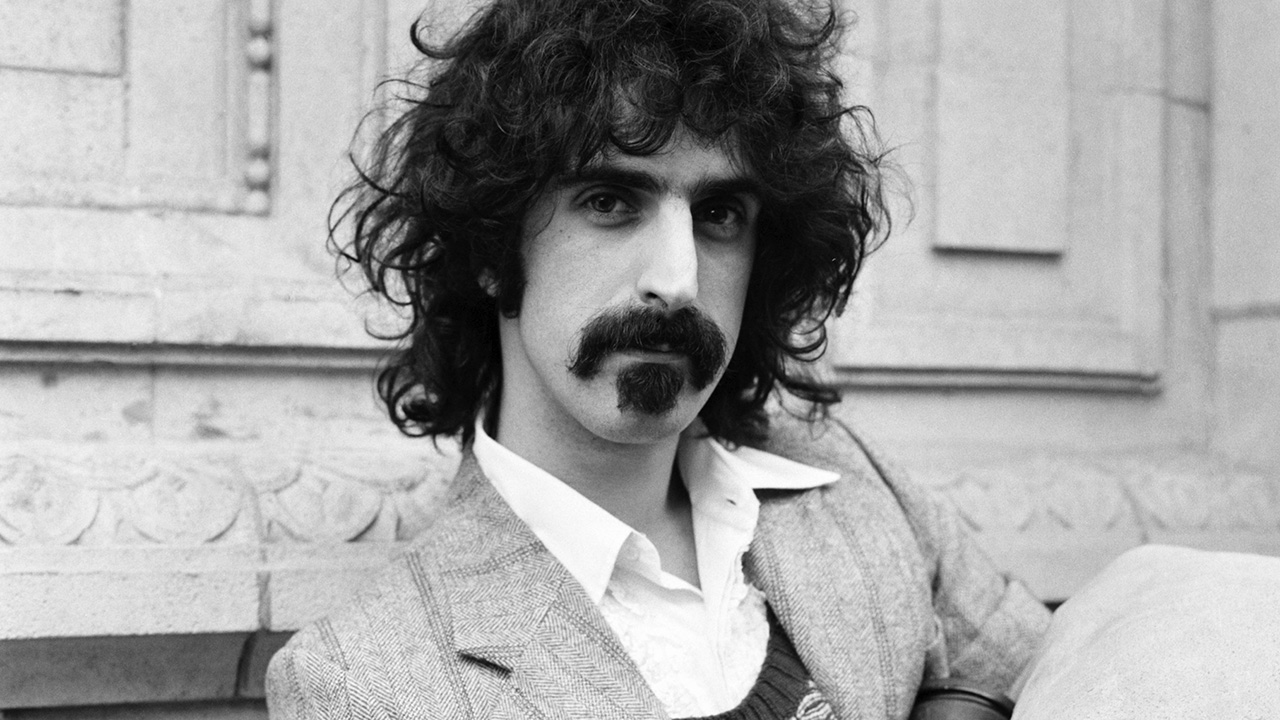

In 2013 Prog ran an archive interview which meant a lot to editor Jerry Ewing and writer Philip Wilding, as Jerry explained at the time:

”Cutting Edge was a magazine myself and Philip worked together on back in 1993, when we were younger and the world was a different place. Somehow we managed to persuade Frank Zappa’s UK PR to grant us an interview, which was duly assigned to Philip, the magazine’s resident Zappaphile. It would prove to be the great man’s final interview – although a noted music magazine would later run one conducted previously, claiming it to be Zappa’s final words.

“I recall the profound emotional effect it had on Philip – not least Frank’s parting words, which still send a shiver of emotion through me to this day. This piece meant a lot to us back then. It still does today. I hope you enjoy it.”

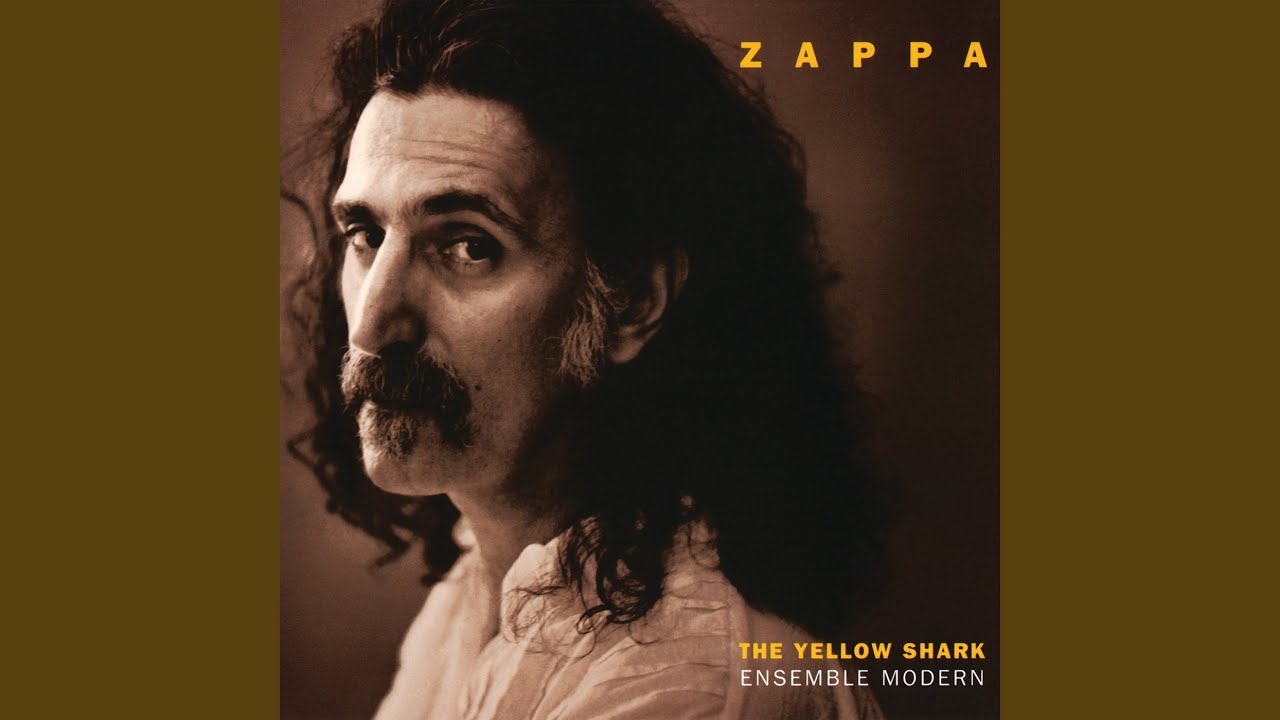

Frank Zappa’s early departure from a series of performances by the Ensemble Modern of his The Yellow Shark at the Frankfurt festival last year again set off rumours that his health was in a serious state of deterioration. Since the announcement by Moon and Dweezil Zappa of their father’s cancer in 1991, he has become the cause of speculation that has, for once, disregarded his supposed outrages, while once again simply choosing to overlook his music. At the time, he confirmed, “I’m not dead, and I have no intention of checking out this week or within the foreseeable future.”

The Yellow Shark is so named after a fibreglass fish that once rested against his fireplace. He finally turned it over to Ensemble Modern’s general manager, Andreas Molich-Zebhauser, with a note: “This is Andreas’ personal yellow shark,” to help it through Customs.

Consequently, the 90-minute piece, consisting of new transcriptions, alongside arrangements of existing Zappa work, Be-Bop Tango, Dog Breath, Uncle Meat, combined here as Dog/Meat, and at the Ensemble’s request, G-Spot Tornado, became The Yellow Shark.

On the given title, Zappa shrugs: “It sounds really good in German, but really dorky in English. What can you do?” A Cageian work, he gives credence to that composer for opening the door to a lot of the possibilities in modern music. It’s another milestone in his more opulent, avant-garde – some might say serious – musical output. Its body is elaborate and occasionally dense with a complexity that is as striking as it is ambitious.

“I’ve never had such an accurate performance at any time for that kind of music that I do,” marvelled Zappa afterwards. Taking up the baton himself to conduct the final G-Spot Tornado movement, as the La La La Human Steps dance ensemble performed around him, the result was a 20-minute standing ovation. The following shows, without Zappa on hand to introduce the work, still managed to sell out at all performances.

“I thought they might,” he admits on the phone from his home in Laurel Canyon. “The dedication of the group to playing it right would take your breath away. The rehearsals under conductor Peter Rundel, trying to get the details worked out, they were meticulous, they’d take your breath away.

"I mean, the organisers were amazed – we were averaging 2,000 people a night, a very diverse audience. And it was good to see that I didn’t have to stand there every night and be Mr Carnival Barker to bring those people in. They just kept coming.”

His orchestral work has also been performed and recorded by Kent Nagano and the London Symphony as well as Pierre Boulez and the Ensemble Inter-Contemporain, the latter also commissioning Zappa’s The Perfect Stranger. While constantly composing new pieces, he’s recently finished an opera which he hopes to have performed in the Vienna festival next year, as well as completing the follow up to his avant-garde ballet, Lumpy Gravy, titled Civilisation: Phase 3, and piecing together a new work, Dance Me This, for use by modern dance groups.

I came back with some real hot news and they decided that they didn’t want to run it

He started composing chamber music at the age of 14, finally frustrated by the fact that he had no friends and if he did they were hardly likely to play it, he succumbed to the idea of his first garage band, the Black-Outs, named after a peppermint schnapps binge that resulted in some of the members collapsing. He later joined the Soul Giants, who by turn became the Mothers Of Invention.

Innovation came almost instantly. His fascination with composer Edgard Varèse – whom he once placed a phone call to in lieu of a 15th birthday present – and a love of the occasional doo-wop 45, which he later lovingly recrafted on Cruisin’ With Ruben And The Jets, ensured a seminal approach to his music that has yet to be equalled, let alone surpassed in its ingenuity.

Dogged by controversy because of a supposed gross-out contest with Alice Cooper, exposing himself on stage – “Ahmet’s probably guilty of all the things that I’ve been accused of” – he was personally attacked for songs such as He’s So Gay and Jewish Princess.

The latter was denounced by the Anti-Defamation League of the B’nai B’rith, who demanded an apology. Zappa, not surprisingly, said no. I mention this, and wonder if people do miss the humour in his music, and he offers a curt: “Usually. Some people get upset.”

Other targets for his ire have been Jesse Jackson, Surgeon General C Everett Koop (whose theory on the development and spread of the AIDS virus Zappa once described as “awful fucking thin”), and a host of televangelists and rednecks, who have all felt the finely-crafted sting of his rebuke.

He still admits to a genuine, sometimes mystified, anger now, though a moral battle of sorts has been won with the removal of Tipper Gore from the PMRC censorship body, offering her resignation as soon as her husband Al took the Democratic Vice Presidency.

I’ve looked foolish before, I’m sure I’ll look foolish again

“It wouldn’t have looked too good in the position she’s now in,” remarks Zappa dryly. Though that figurehead may have been dismissed, he still expresses genuine and quite understandable alarm at the introduction of the Child Protection Act into the American Constitution.

Originally designed to combat pornographers by allowing the justice system to impound their property and possessions, consequently it is now able to be upheld in a court of law if a judge deems any material obscene – the most obvious implication being album sleeves and lyrics. But the list of possibilities is endless.

When I ask why other artists don’t adopt a similar stand to Zappa – he defended Prince’s Darling Nikki before the Senate Commerce Committee, “but Prince failed to show up” – he sighs, noncommittally. “Because their managers sit them down and tell them to shut the fuck up.”

Perceived as having a total disregard for any so-called norms, but recognised as possessing an astute business mind, Zappa’s reputation preceded him when he was offered the chance to host a talk show on the Financial News Network (FNN).

“I went and did this special on the Soviet Union, did interviews and so forth and came back to put the show on air. But the people who ran FNN were so terrified they put a disclaimer on before the programme saying that, ‘Mr Zappa’s opinions are his own and blah-blah-blah.’ I don’t know what the fuck they thought I was going to say once I got on there. It was very strange.

“I had this interview with a guy from a financial research institute in Moscow who was talking about how many military factories they were willing to convert to the manufacture of consumer goods. And this was like three years ago. I had coverage of the first Russian beauty parlour. An interview with a guy from the Australian Embassy who was telling me about the Australians working in conjunction with the Russians to go into the Aerospace business together...” he tails off, mildly disgusted. “I came back with some real hot news and they decided that they didn’t want to run it.”

They told me that Jimmy Carter and myself were the biggest enemies of the Communist Czech State. Which was a real shock to me

I suggest, half-jokingly, that there’s an FBI file on Zappa somewhere. “I’m sure there is. I think they keep their eye on me. No, it doesn’t worry me at all.” He answers before I’ve managed to raise that question.

Firsthand experience of the failing Soviet system prompted him to set up the Why Not? Inc company to help develop business in the former Eastern Bloc community. “There’s this big sports complex right in the middle of Moscow. It’s where the Lenin Stadium is; they have all these facilities there and they were looking for some Western partners to come in. I managed to persuade a couple of people to go to Moscow and talk to this guy, Vladimir, who turned out not to be a very good businessman at all.

When he saw that he actually had Western businessmen sitting in his office taking notes he decided to triple the price of everything he had quoted to me. They just walked out saying, ‘This guy’s crazy.’”

A pause. “I’ve looked foolish before, I’m sure I’ll look foolish again. And I’m not doing anything with Why Not? now. It’s very difficult for me to travel at the moment and you can’t do that kind of business sitting at home. I just had to let it go.”

That said, his connection with the former Eastern Bloc remains. His brief appointment as Czechoslovakia’s Special Ambassador to the West on Trade, Culture and Tourism was instantly scuppered by the then-Secretary of State, James Baker, who allegedly carried a grudge against Zappa after his remarks that Mrs Susan Baker was simply a bored housewife who had nothing better to do than join forces with Tipper Gore and the PMRC.

He also invited prominent Czech politician Vaclav Havel (whose favourite Zappa album is Bongo Fury) onto his FNN chat show. The interview never happened, but the interest in Zappa from behind the Iron Curtain became very apparent.

“I heard that when I was in Prague. Apparently, my stuff had been slipping in there since 1966 or 1967. They were really big fans of the Absolutely Free album, specifically, I think, because of the song Plastic People. It became some sort of underground anthem. They told me that Jimmy Carter and myself were the biggest enemies of the Communist Czech State. Which was a real shock to me.”

Basically, it’s dangerous to even go to the schools because of the guns and the drugs

You were right up there alongside Jimmy Carter? A brief, throaty chuckle. “I don’t know about that; he’s a born-again Christian. I don’t think I belong in that category.” But you were a good Catholic boy? “No, I got out while the going was good. They only had my brain until I was 18, then I wised up. I was out of there.”

Zappa chose to remove Dweezil, Ahmet and Moon out of the Californian education system at the earliest possible moment, when they were 15. Diva, 13, still has two years to go. Didn’t that in some way hamper their upbringing? “No, it didn’t detract from their education or upbringing.”

Dweezil now describes that upbringing as, “Not being a problem in the slightest. He [Frank] was totally supportive in everything we did. But I was never one of those kids anyway.”

“Basically, it’s dangerous to even go to the schools because of the guns and the drugs,” says Zappa, his voice now noticeably husky and a little dry. “That’s one thing. The other thing is that what they teach is so worthless and behind time, it’s more like a warehouse to keep your teenagers out of your face for a couple of hours per day. It’s not a place of education.”

And before they skipped the system? “I made them do their homework just like they were supposed to.”

Whenever I’ve interviewed both sons, most recently for their Shampoohorn record, they’ve had nothing but a genuine respect for you. They’re very well adjusted coming from what most people would purport to be a genuinely baffling background. “I got lucky. They like me, I like them too. We, all of us, like each other. We have a very nice family.”

Before the formation of the Zappa and Barking Pumpkin labels, he’d taken legal action against both his former labels, Warner Brothers and CBS, attempting to rectify the situation by setting up the short-lived Straight Records. “We were doing it with independent distribution, and that way you don’t have any money to collect from local retailers. You ship to them, they pay you within 90 days, and if they don’t you have to sue them. But you have to sue every one of them in the State where they live.” A sigh. “That’ll fuck you up pretty good.”

There’s a few stations that’ll play Zappa; very few, and then usually after midnight

Like having to get them in their hometown over here? More laughter. “Oh yeah, look at my track record – me and the Old Bailey are just like that,” he chuckles, recalling a long-distant and failed attempt to sue the Royal Albert Hall for cancelling one of his shows.

We chat some more. About his foreshadowing of the LA Riots and the AIDS debate with The Blue Light and Thing Fish respectively. About what kind of hope, if any, is left (“depends on what you’re hoping for”), his much-loved Synclavier (“It cost as much as six Lamborghinis; my work wouldn’t have been so prolific without it – it makes the process faster”) and the suppression of his music in the States (“There’s a few stations that’ll play Zappa; very few, and then usually after midnight”).

And then we discuss his announcement in 1991 that he would run for president. “The system is as archaic as the Soviet one that’s just fallen apart. It’s so clumsy, so stupid, so inequitable and so expensive. It should just be scaled down and parts of it done away with. The ability to govern should be returned to local regions. But I don’t think you could get elected on a platform like that.”

He falls silent for a moment. “But it’s too late to talk about that. I’m getting tired now, have you got one last question?”

Only as to how you’re feeling.

“It’s up and down.” he says quietly. “And today, I’m not having a good day.”