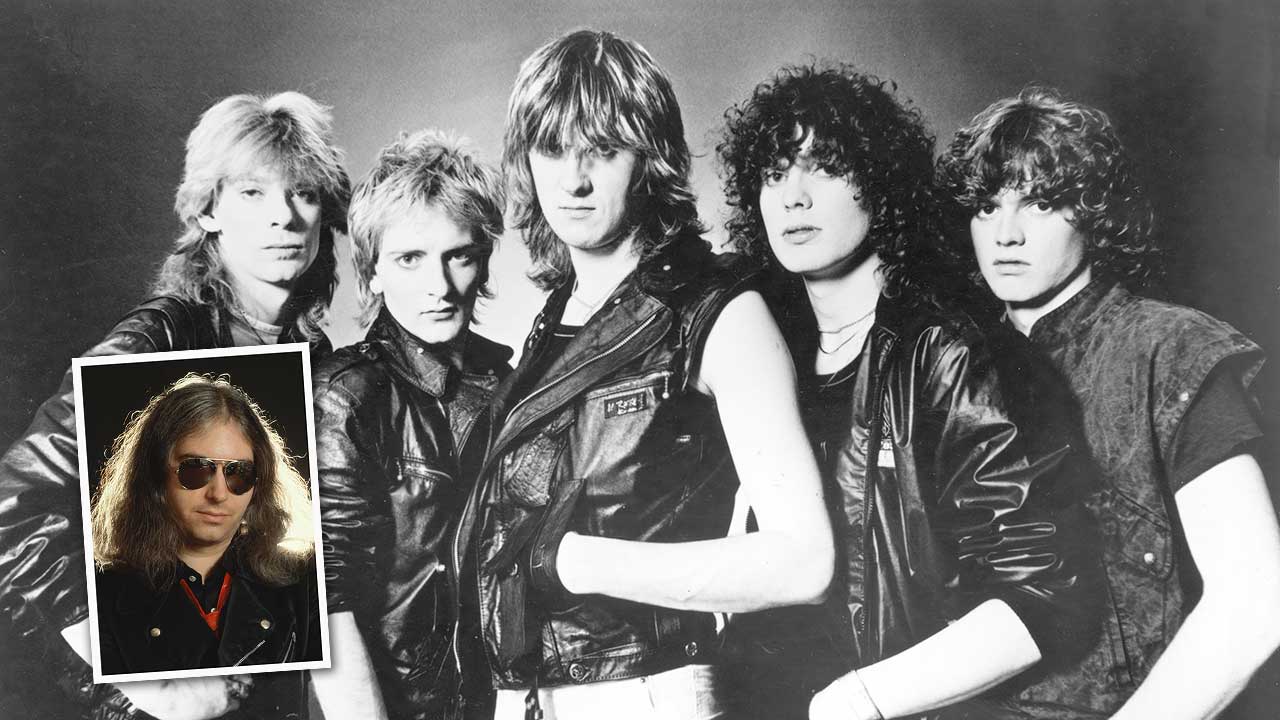

The story of Def Leppard's Jim Steinman sessions, the most expensive unreleased album ever

When Def Leppard teamed up with Jim Steinman they expected big things. What they got was a huge food bill

The first time Jim Steinman met Def Leppard, in the summer of 1984, he delivered an emphatic mission statement: “I think we can make beautiful music together.”

Steinman had just signed up to be the producer of Leppard’s fourth album, the follow-up to their six-million-selling Pyromania. The band had already begun work on the album, and had recorded several demos on a rudimentary four- track machine.

A self-confident New Yorker, Steinman carried a big reputation as the creator of one of the biggest rock albums of all time: Meat Loaf’s Bat Out Of Hell. And when he arrived in Dublin to meet the five members of Def Leppard at the house they shared at 1 St Helens Road, in the Booterstown area, he gave them the full charm offensive.

“We all sat in the living room drinking tea,” recalls Leppard singer Joe Elliott. “And Jim says: ‘I’ve heard your demos. I really dig ’em, man!’ It was that very American bullshit.”

Guitarist Phil Collen was impressed by some of what Steinman said. “He talked about recreating Phil Spector’s ‘Wall Of Sound’ while staying true to Def Leppard. It sounded like it could be cool.” But as Steinman laid it on with a trowel, alarm bells started ringing in Joe Elliott’s head.

“Jim was a funny guy, very eccentric,” Elliott says. “But you could sit down with Charles Manson for 20 minutes and probably come away saying: ‘Hey, he’s not that bad.’ And in that first meeting, we realised that Jim was in a completely different orbit to us. I got this uncomfortable feeling."

It was too late. The deal had been done: Steinman was their man. And what resulted was one of the most expensive mistakes in the history of rock’n’roll.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Jim Steinman was Def Leppard’s producer for just eight weeks before they cancelled his contract. None of the recordings that the band made with him were ever released. And it was only after Steinman was replaced by ‘Mutt’ Lange, the producer of Pyromania, that Leppard were able to complete the album they named Hysteria. For Def Leppard, working with Jim Steinman was a disaster.

“We thought we’d got the Ferrari,” says Collen. “In reality, we’d got a second-hand Cortina.

The truth is that Def Leppard never wanted Steinman as their producer in the first place. They had planned to work again with Lange, whose influence on Leppard’s sound, as producer and co-songwriter, was so important that he was considered their “sixth member”.

But in April 1984, after Lange had written several songs with the band in Dublin, he told them he was too exhausted to produce their new album, having worked flat out for years on end, making hit records for AC/DC, Foreigner and The Cars as well as Leppard.

“When Mutt dropped that bombshell, we had an emergency meeting,” Elliott says. Present were the band and their co-managers Peter Mensch and Cliff Burnstein.

“We were desperate,” he admits. “Who the hell do you get to replace Mutt Lange?”

Approaches were made to Roxy Music/Sex Pistols producer Chris Thomas, and Trevor Horn, former member of The Buggles and Yes and producer of Frankie Goes To Hollywood. Both said they were too busy. Phil Collins was also briefly considered.

It was Cliff Burnstein who suggested Steinman. But there was a flaw in his logic: although Steinman wrote the songs for Bat Out Of Hell, it was actually Todd Rundgren who produced that album.

“Steinman was not a producer,” Elliott says. “I pointed that out. But because Mutt was a producer who assists in songwriting and arrangements, Cliff thought we might need help more in the songwriting department than in the sonics of the record. Cliff got that completely wrong. But at the time, Steinman was literally the only option we had, so we ended up going with him.”

When Steinman was hired, Elliott consulted Lange, who told him: “Give it a go – and if it doesn’t work, get rid of the guy.” Elliott laughs when he reflects on that advice. “It was exactly what happened,” he says, “because Steinman was less than useless!”

August 11, 1984 was Steinman’s first day in the producer’s chair at Wisseloord studios in Hilversum, Holland. Working alongside him was Neil Dorfsman, described by Collen as “a fucking brilliant engineer”. But from the start, Elliott sensed trouble.

“That first afternoon, we were warming up,” he says. “We played a loose, Stones-y version of Don’t Shoot Shotgun – just the riff and a part of the melody. We didn’t even have the chorus then. And Steinman says: ‘I think we got that one.’ We all looked at each other, and Phil said: ‘We haven’t even tuned up yet!’ Steinman says: ‘Yeah, but it’s got a vibe.’ That wasn’t a good sign.”

It went downhill from there. In the days that followed, Steinman suggested some song titles. Use It Or Lose It was one. “What he assumed was a good title, we thought was shit,” Collen says. “His ideas seemed a bit hokey. Maybe it was a class thing. It was obvious that we were way more ‘street’ than he was. Jim’s stuff was a bit theatrical, which is great, but it wasn’t us. We were polar opposites.”

This cultural divide was also evident in another of Steinman’s ideas. For the balls-out Run Riot, he proposed a Bat Out Of Hell-style flourish.

“He wanted to put a synthesiser run on it,” Elliott says. “Diddle diddle diddle… Like Rick Wakeman on Siberian Khatru by Yes. You couldn’t have come up with a worse idea, in our eyes.”

Across eight weeks, Steinman and Def Leppard worked on seven songs. In addition to Don’t Shoot Shotgun and Run Riot there was Animal, Women, Gods Of War, Love And Affection – all titles that would make it on to the final version of Hysteria – plus a song called Love Bites that was later rewritten as I Wanna Be Your Hero.

“They were works in progress,” Collen explains. “They sounded… okay. But we’d sold six million of Pyromania, and for the follow-up you didn’t want to do less, you wanted to do more.”

“We didn’t want to make Pyromania II,” Elliott says. “We were looking to make a masterpiece of production and songwriting. We didn’t want to throw out an album that would have sounded like anything else that came out in 1985.”

Jim Steinman simply didn’t understand Def Leppard as Mutt Lange did.

“There was a flow of ideas and inspiration that we got from Mutt,” Collen says. “That’s what we were waiting for from Steinman. And it never happened. Mutt wants to create something spectacular – almost like a third dimension, wildebeest sweeping majestically past… Steinman just came in and let us record. And what he recorded was just ordinary. It didn’t even sound as good as our original demos.”

Adding to the band’s frustration was a sense that Steinman was not fully focused on the job at hand.

“We’d be in the studio at 11am,” Elliott recalls. “Steinman would stumble in at 3pm because he’d been up every night writing Bat Out Of Hell II. He wasn’t giving us his full attention.”

Elliott also claims that Steinman racked up an enormous bill for food. “He would look at a menu and order one of everything. Every night, on our dime, there would be a fucking banquet of food.”

But it was when Steinman demanded a better quality of carpet in the studio’s control room that Elliott decided he’d had enough. The singer told the rest of the band: “We should be changing the producer before we change the fucking carpet.”

Another of Def Leppard’s emergency meetings was called. This time it was just the five band members.

“The problem was that Steinman wasn’t adding anything,” Collen says. “And if you’re going to pay someone to produce your album, you want them to be better than you are – at the very least.”

When the meeting was over, a phone call was made to Mensch and Burnstein. The message was: “Get rid of this guy!”

By mid-October, Steinman was gone. Neil Dorfsman went with him. The band brought in another engineer, Nigel Green, who had worked with them on Pyromania. They recorded with Green until the Christmas break, during which the unthinkable happened – drummer Rick Allen lost his left arm in a car crash on New Year’s Eve.

It was while Allen was recovering in hospital that he persuaded Lange to come back on board and finish the album. With Lange, the band re-recorded every track from scratch.

Hysteria was finally released in August 1987 and went on to become a huge hit – the biggest album of Def Leppard’s career, with more than 20 million copies sold to date.

Steinman never got his new carpet, but he got his payoff – “a big six-figure sum”, according to Elliott. “We had to sell a lot of records to pay him off. Jim Steinman made a lot of money out of Def Leppard for doing very little work. He’s a lucky man in that respect.”

Almost 30 years down the line, Elliott still has a box of tapes marked ‘Hysteria: The Steinman Sessions’. And he thinks it is best for both parties that these tapes remain unheard.

“We would never release that stuff,” he says. “There’s nothing finished. It’s like the worst bootleg you’ve ever heard. Those tapes are locked away in my library. And that’s where they’ll stay."

Visit the Def Leppard Vault for archive material that is being released.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”