“Some guy who obviously didn’t recognise me said, ‘You just ruined a classic song.’ But another chap replied, ‘He’s allowed. He wrote the song!’”: Keith Emerson’s disastrous karaoke incident

The keyboard legend's jam-packed career saw interactions with a varied cast from the ‘strange’ Dario Argento to Motörhead’s Lemmy

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

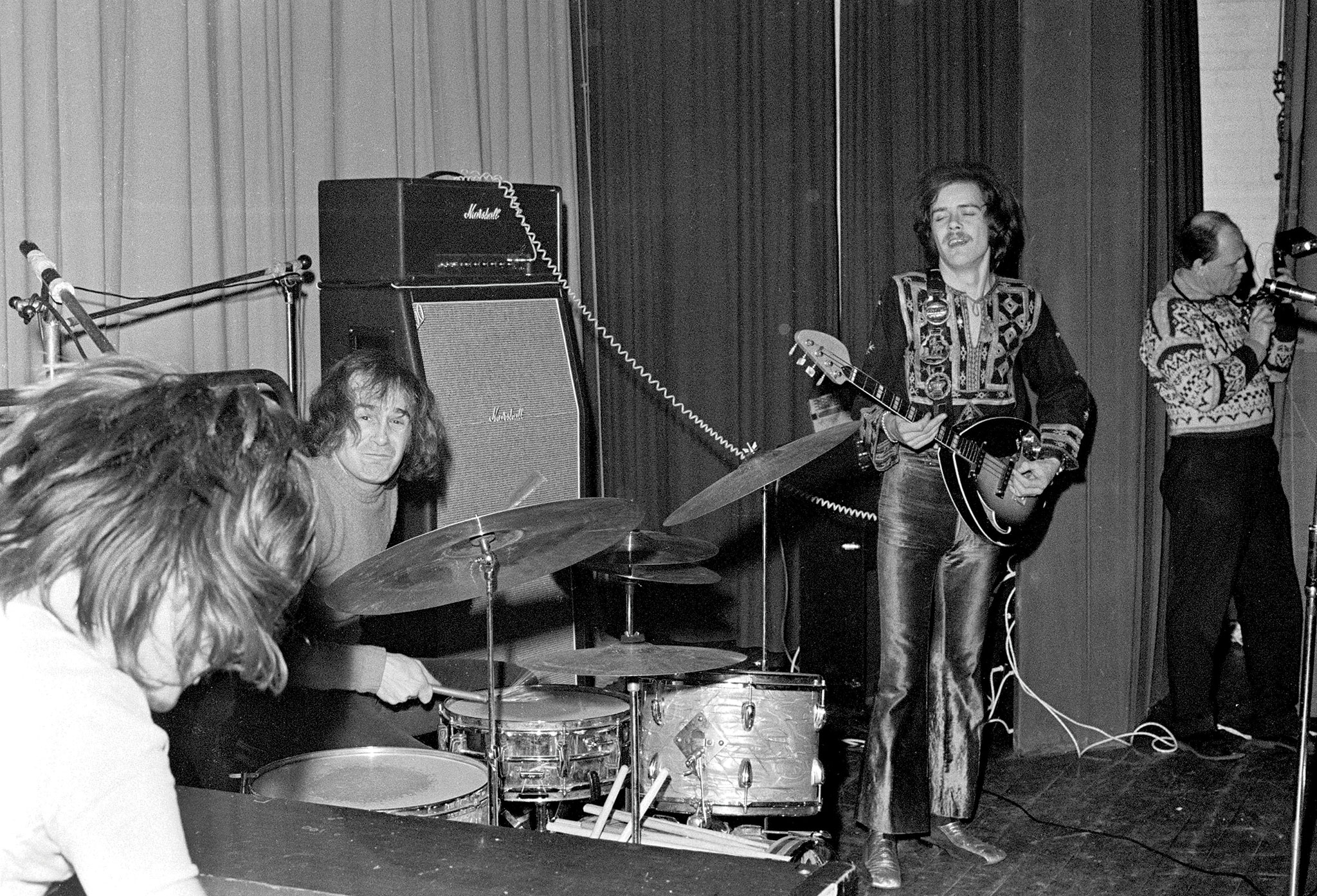

Mostly renowned in prog circles for being firstly a member of The Nice and then ELP, Keith Emerson built a reputation as a musical pioneer. Moreover, he was one of the most colourful characters in rock – whether stabbing his keyboard with knives or playing while suspended in mid‑air, he was always the centre of attention.

In 2015, the year before his death, he spoke to Prog about his life and times.

ELP made their proper live debut at the Isle Of Wight Festival in 1970. What do you recall of that concert?

Well, I know that nobody expected much from us. We’d done a warm-up gig in Plymouth. But even so, this was a leap into the unknown. We got a decent enough reaction, so much so that the camera crew who had initially ignored us suddenly wanted footage of the band. A lot of that still hasn’t been seen.

There’s a great story that you wanted Jimi Hendrix to join ELP. Is that true?

Ha, no. This was a myth invented by the music press when we started to become well-known. They thought the idea of a band called HELP was funny. I had toured previously with Hendrix, which might be where that story originated. But by then I’d had enough of working with guitarists!

Talking of Hendrix, you and he did have one thing in common: Lemmy was a roadie for each of you. He played an important part in your developing knife act on the keyboards, didn’t he?

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Ah, Lemmy, yes. I had already begun to stab knives into my keys, which I found helped the sustain. But these were small kitchen knives. So one day Lemmy came to me and said, “If you’re gonna put knives into the keyboards, then you’ve got to do it properly.” And he gave me some German army ones he had, which were much bigger. They certainly got noticed a lot more!

Greg Lake wasn’t the first choice for bassist in ELP, was he?

No. I wanted Chris Squire but he was too busy at the time. Carl Palmer always told me I should have gone for John Wetton…

Unlike some of your keyboard contemporaries, you never went to music college, did you?

No, I would say I’m self-taught. But I had three piano teachers when my family lived in Sussex. I had lessons from the age of three. Carol Smith, who was one of those teachers, once said that I was a very quiet boy and she couldn’t understand how I became a raving lunatic!

You were a quiet child?

I was very studious at school and really kept in the background. I never knew what to do with a woman until I was 22 – after which there was no holding me back! But I was a very serious child. I used to walk around with Beethoven sonatas under my arm. However, I was very good at avoiding being beaten up by the bullies. That was because I could also play Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard songs. So, they thought I was kind of cool and left me alone.

Would you regard yourself as an artist or an entertainer?

First and foremost, I’m a composer. When I think of entertainers in music, I think of people like David Bowie, who created characters onstage. I was nothing like that. If I had to choose between artistry and entertainment, then I would have to say that I am more of the former. But I would like to be known as a composer before anything else.

Yet you did become a showman, and that has certainly helped to define your career.

Well, when you’re stuck behind a keyboard then you have to do something to attract attention to yourself.

Like your flying piano?

Yes! The fact that I could play while suspended in mid‑air made me the centre of attention. And I have to say that I loved it. That was such an exhilarating experience. Dave Brubeck, the pianist who is one of my heroes, was keen to know how it was done. I met him a lot of times, but when he finally asked me about the flying piano, he was close to 90. I said to Dave that he shouldn’t even think about attempting it at his age!

It was a dangerous thing for you to do at the time, wasn’t it?

Oh yes, but I’ve always loved to challenge myself by doing things that others would call ‘dangerous’. And when you’re up in the air sitting at a piano, it really is more exciting than frightening.

Do you ever think about dying?

Not really. But when a good friend dies, as happened recently with Chris Squire, then it does hit home and make you appreciate that you have to ensure every second in your life counts.

Did you ever consider giving up playing the keyboard and taking up the guitar?

Actually, I did go through that stage. At one point I thought I would stand a far better chance of making it in a band. My father, who was an amateur musician himself, got me a guitar and I spent eight months trying to become proficient at playing the instrument. But it was hopeless. I was never gonna rival Jeff Beck!

Do you have a talent for singing?

You are joking. My girlfriend recently persuaded me, against my better judgement, to go to a karaoke club with her in California. It was a disaster. I looked at the list of songs they had on their list, and there was Karn Evil. So, I thought I’d try to do that. When the lyrics scrolled up in front me, they’d been changed. There were a couple of lines the club thought would be offensive, so they’d been cut. Anyway, I managed to bumble through the song.

As I left the stage, some guy who obviously didn’t recognise me said, “You just ruined a classic song.” But another chap replied, “He’s allowed. He wrote the fucking song!” It made me appreciate what Greg Lake had to do for all those years.

It’s often been said that the three of you in ELP never got on.

I regard the three of us as having a similar relationship to the one Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend had in The Who. There was antagonism between us. But when you’ve spent 10 weeks out on the road together, as we often did, then you got sick of the sight of one another. That wasn’t just peculiar to ELP – it applies to any band.

But did this affect the band’s live performances at all?

Never. I can honestly say we were thoroughly professional. Once we stepped out on that stage, all thoughts of problems between us disappeared. All we wanted to do was do our best for the fans.

Your first movie soundtrack was Inferno, a Dario Argento horror film. Did you particularly want to get into horror?

What happened was that after ELP had done Works Volume 1, I told our manager, Stewart Young, that I really wanted to do a film soundtrack. I didn’t really care what genre it was in – I just wanted the new challenge. Now at the time, Stewart had been talking to Dario Argento, and he suggested I do his next movie. Argento was into the idea so I flew to Rome to meet him.

How did you get on with him?

He was a little strange, but maybe that was to be expected, given the films he’d previously made. He gave me the script and it was tough to follow. It seemed to be about witches and a house within a house. But there was one scene that hooked me. It has a guy who hates cats, and he piles a load of cats into a bag and takes them to the river, to be drowned. As he pokes them into the river with his stick, a huge epidemic of rats spill out and devour him. I thought that was great!

What was your reaction to seeing the final film?

I saw it at the premiere in Rome and there were so many people screaming in terror and walking out, it was brilliant. These days Inferno wouldn’t even raise a whimper, but back then, in 1980, it caused a sensation. I loved being a part of it, and it gave me the impetus to do a lot more soundtracks.

You recently made a live comeback in the UK, playing at The Barbican. But you’ve since been critical of the behaviour of some of the BBC Concert Orchestra who played with you. What went wrong?

Frank Zappa, whom I got to know quite well, once asked me what was wrong with British orchestras. I told him it was bureaucracy. Most of the BBC Concert Orchestra behaved impeccably, but there were two or three members who spoiled it for everyone by obviously putting earplugs in, and also making a show of walking offstage at one juncture. To be frank, I thought their behaviour was disgraceful.

Hasn’t there always been an ongoing problem between orchestras and rock musicians?

In the past, there has been, yes. But for the most part, it has disappeared. I’ve performed with world-class orchestras everywhere and there’s never a problem. But at The Barbican, there were difficulties. I became a nervous wreck during the rehearsals. They insisted we had to have a perspex screen erected around the Moog synthesiser, when the whole concert was to celebrate the Moog!

Has this put you off working with orchestras in the future?

Not at all. As I’ve already said, I’ve successfully worked with a lot of different orchestras all over the world, and I hope to carry on composing music that will be played by orchestras in the future. But what it does mean is that if the BBC Concert Orchestra is to work again with a rock band, then some of the members will have to change their attitude.

You mentioned that you were a nervous wreck after rehearsing for The Barbican show, which brings up the question of whether you still get nervous in general before playing live?

Oh yes. I’m still nervous every time I go onstage. But in my opinion, having a little stage fright is a good thing. It keeps you on your toes. If you don’t have that nervousness then you could easily become overconfident and lose your edge. So I would never want to lose that feeling in the pit of my stomach.

There has been talk of you putting together a documentary on your life. Is that still happening?

Oh yes. It’s a work in progress. I’m gonna call it Pictures Of An Exhibitionist. A lot of interviews have already been done for this and I’ve also found quite a bit of unseen footage which should make it very interesting. Right now I have no clue when it will be finished. The idea is for it to be a complete look back at my life, and it will hopefully give people an insight into what makes Keith Emerson the man he has become.

Some people would say that a lot of your music appeals solely to the male psyche, and not to the female one.

In the ELP days, what I composed was definitely music men liked, as opposed to women. It was Greg who came up with the songs that brought in the females. But that had nothing to do with any sexual preferences. It was simply an artistic expression. I think in more recent times, women have been attracted a lot more to my music than previously.

Did it sit comfortably with you being called a prog rock musician in the ELP days?

When I was in The Nice and then at the start of ELP, nobody had ever heard of progressive music. What we did had some jazz in it, a little blues and also had the classical references. It was only later on that people began to call our music ‘progressive’, and that’s when the genre began to grow. With hindsight, I’d say that ELP were the pioneers of progressive rock, though.

You were part of a very short-lived supergroup called The Best in 1990. What was that all about?

That happened because I used to jam a lot in California with Jeff Baxter of Steely Dan and The Doobie Brothers – well, he prefers to call himself Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter. We were good friends, and he called me up one day with the idea of putting together a band with him on guitar, myself, Joe Walsh of the Eagles on guitar, John Entwistle of The Who on bass and Simon Phillips on drums. Actually, Zak Starkey of The Who was the original choice of drummer, but he wasn’t available.

The band name was a little arrogant, wasn’t it?

I agree, but Jeff insisted on it. I’d have been more comfortable with a different name. However, I was outvoted by the other guys. Anyway, the idea was that the live set we did would feature songs from our respective careers.

But the band didn’t last long. What went wrong?

Nothing actually went wrong, but we found that our schedules were too busy to get the band off the ground. We did one show in Yokohama, Japan, and that went really well. It’s a shame we couldn’t have taken it further.

You’ve written your autobiography, which is also called Pictures Of An Exhibitionist, but do you have any ambitions to write other books?

Actually, I would love to write children’s stories. I have four grandchildren and they’re just so funny. They’re great, and I love reading to them. In fact, I’ve come up with some stories for them which I’ve written myself, but so far are unpublished. However, I am pursuing possible ways of getting these into the public domain.

What are they about?

I used to have a cockatoo that would sit on my piano and it was a great little character. It would react differently depending on what music I was playing at the time. So, I wrote some stories based around that bird. I think we can all sometimes forget how amazing children are, and I love having them around to remind me about how fantastic it is to be a child.

Talking of childhood, what is your earliest memory?

Well, I was born during the Second World War and I recall the sound of bombs dropping.

But you were less than one year old when the war ended.

It may seem strange, but I definitely do remember that happening. I also recall at the age of two going round all the bomb sites in the area looking for bits of shrapnel. At the time, they were as valued as marbles and conkers to a small boy. If you had cool pieces of shrapnel, you could swap them for almost anything.

We’re only two years off the 50th anniversary of The Nice. Can you see any sort of band reunion to mark the occasion?

Well, Brian [Davison, drums] died a few years ago [2008], and without him, how could we have any sort of meaningful reunion? It only leaves myself and Lee Jackson [bass], and both of us agree that there’s no chance of us doing anything under the name of The Nice. It would have to have been the three of us, but now that Brian’s no longer with us, The Nice should remain in the past.

Are you and Lee Jackson still on good terms today?

Absolutely. We talk all the time. Lee is my oldest friend from the music business, and one of my closest friends as well.

How about an ELP reformation for one final time. Could that happen?

I don’t know. I’m not thinking about that. I would rather look ahead to fresh challenges than think back and try to recreate what I’ve done before. I’m not definitely ruling it out because as long as the three of us are still alive, it’s always a possibility. But it’s certainly not on my radar right now.

Unfortunately, Greg Lake has been seriously ill. Have you been in touch with him at all?

I have reached out to Greg and tried to talk to him but so far I haven’t been able to do so. But that doesn’t matter. All I hope is that he’s going to be OK.

Do you have a list of things you still want to do?

Not really. But I do have certain things I’d love to do. For instance, it’s an ambition of mine to sit in the cockpit of a Spitfire. That would just be amazing. The closest I’ve got is sitting inside a Northrop P-61 Black Widow, which was an American plane from the Second World War. That was an experience, but nothing could compare to having the chance to be in a Spitfire!

What about on the musical side: are there things you still want to achieve in your career?

I am definitely still very active, and want to carry on composing music for orchestras as long as I can. That’s where my heart lies now.

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.