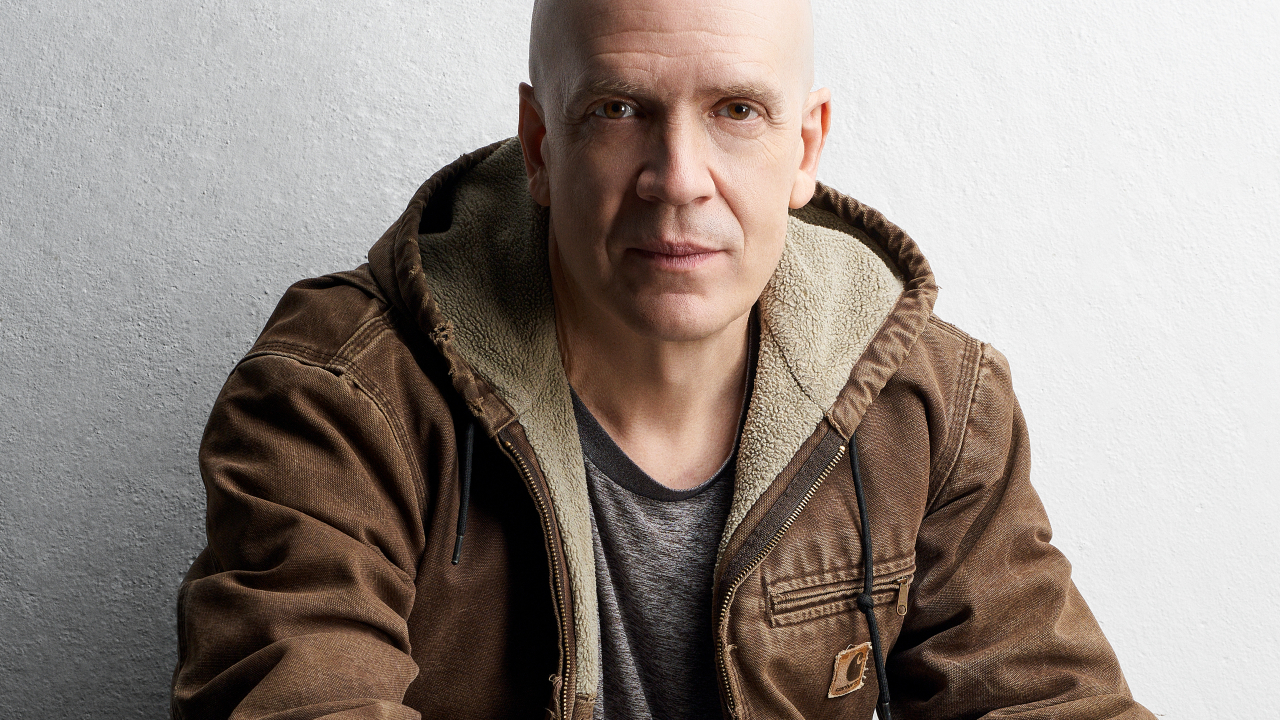

The Prog Interview: John Petrucci

The guitar guru ponders 30 years with Dream Theater, that fractious split with drummer Mike Portnoy, and how life is always better with good food, good wine and a set of barbells.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

John Petrucci has become one of the most influential guitarists of his generation. A founding member of Dream Theater, his distinctive style and technical skill have been mainstays of the band over the last 30 years. He’s also worked as part of the Liquid Tension Experiment project, which released two instrumental albums in the late 90s, and appeared as part of the G3 tour alongside Steve Vai and Joe Satriani. There was also a solo album, 2005’s Suspended Animation, but due to his constant workload, he hasn’t found the time to record a follow‑up. “It’s crazy and driving me nuts!” he says.

Still living on Long Island, New York, where he was born and raised, a few miles from where Dream Theater played their first live shows, Petrucci recalls his short stint at the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Boston, slicing salami in a deli, and the good fortune and sadder aspects of Dream Theater’s development over the last three decades. For all his onstage persona and adoration by fans and fellow guitarists alike, it’s clear from speaking to Petrucci that he retains a sense of self-effacing modesty that’s at odds with many of his contemporaries. He’s also appreciative of family life and appreciates the sacrifices that have been made to allow him to spend weeks away from home, and how, when he does return, there’s nothing he likes more than cooking food for his family on his garden terrace.

There’s also excited talk about the next Dream Theater album, while he quashes rumours that he once briefly fell asleep onstage during a performance of Metropolis – Part 1 in Japan. First, though, Petrucci looks back with a degree of astonishment that Dream Theater are still continuing to thrive and grow – and critically remain relevant – this far into their career.

Article continues below

The band are celebrating their 30th anniversary this year. Do you ever look back and think, “How the hell did that happen?”

Yeah, I think about that all the time. It’s really a long time and to be able to do what we’re doing, playing the style of music that we play, has been amazing. We really couldn’t have imagined this going back 30 years or so. We were young teenagers going to see Rush and Iron Maiden in concert, just dreaming of doing it, so it’s still crazy to me.

Were your parents horrified when you decided to leave Berklee College of Music after only a year?

Definitely! It took some convincing for them to send me to Berklee in the first place. I was always a really good student at school and my father especially was hoping I’d have other plans for my life. He would tell me I needed something else to fall back on. But I kept saying the same thing to him that every 17- or 18-year-old kid who is into music says: “Music is my life, I’m never going to fall back!” Fortunately for me, it was true.

It must have been a relief for them once your career took off…

Yes, luckily it worked out and my parents ended up being really supportive and my father was really proud, but deciding to leave Berklee after all that convincing? Let’s just say it was a fun conversation. Even after we left, we all got jobs working during the day and getting together at night to practise, but we still had this tunnel vision of making it.

I remember saying to my dad what every 17- or 18-year-old kid who is into music says: ‘Music is my life, I’m never going to fall back!’ Fortunately for me, it was true.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

You got a job working in a deli, slicing meat, so that must have motivated you even more.

Yeah, exactly. Eventually it got better as I could make money doing what I do in music. So if that meant giving guitar lessons in a music store, for me that was better than painting houses or whatever. It made more sense and helped me to hone my guitar playing as well.

Were there ever any times when you felt the band wouldn’t make it?

Oh yes, especially after the first album [1989’s When Dream And Day Unite]. Leading up to that album was exciting but after it was released, there was this whole period of nothing going on. We all had these day jobs and we started to think maybe that was our taste. Even though there was still that passion, the reality hit and it never worked out the way we felt it would.

Have you ever thought about what route your life may have taken if things had fallen apart for the band after that first album?

That’s a good question. I have to wonder. No matter what would have happened with the band and the guys I was playing with, I think I would always have been a musician and would have chosen a different route to get there. I got the bug when I was pretty young and was always into the creative arts.

Which arts were you into?

I used to draw and paint, write stories and draw, and then I got into music. So I couldn’t picture myself doing anything outside of the arts, even if at that time everything fell apart.

Do you think there was a certain amount of fortunate timing in the way the band eventually made it?

I’ve always thought that all the pieces have to be in place for success to happen. You can be out at the wrong time stylistically and in some ways, in the early 90s, we were. There was a bit of a void for what we were doing as the sound of 70s prog wasn’t there any more and metal was just getting bigger and bigger. I mean, I could be wrong but I don’t even think there was a term called ‘progressive metal’ back then. It was just what we did and what we wanted to do.

You took a lot of criticism for that attitude though, especially in your early years.

Yeah, well, you just ignore it. When we first started, we got a ton of that kind of criticism. They’d say our songs were too long, that we didn’t know how to write songs, how the music was too complicated, the arrangements were too busy and how everyone was overplaying. But we just continued to do what we felt was right musically because that was just the kind of music we wanted to play together.

**

So there must have been a sense of satisfaction at the way things turned out?**

It’s kind of cool and it’s a testament to really sticking to what you believe in creatively and then coming out on the other side. You have to ignore those criticisms as it only creates self‑doubt and then you get uneasy about what you’re doing. If the music doesn’t come from the heart then it’s all over. Now it turns out those qualities for which we were criticised were actually the ones that were embraced and praised, and even influenced other musicians.

There are certainly many bands now who are releasing albums in the Dream Theater style. Does that put the pressure on you to try to keep ahead of the pack?

Within all of the guys in the band, we always want to push ourselves as musicians. There’s an element that’s almost a competitive nature where we say we have to continue to push ourselves. Whether we’re at the head or the back of the pack is anyone’s call, but we have to always want to do better.

Even given your success, that still drives you?

Oh yes. It’s just a competitive nature we all have and it’s healthy because there’s no malice in that. It’s just a drive and a push to want to always be the best.

I try to get in the gym five or six days a week, and being consistent with training on the road is a challenge. It takes discipline and determination.

It must still be odd to be referred to as a ‘guitar god’ though…

You know what, I’m really not comfortable with the term as it sounds so pompous! I understand the concept of younger players looking up to musicians as I viewed players the same way when I was a teenager. I just looked up to them and wanted to be that person. People like Alex Lifeson [Rush guitarist], I was totally floored by. I know people use terms like ‘rock star’ or ‘guitar god’ all the time, but it’s just so over the top and I would never refer to myself as that.

That acclaim must add pressure though. Are you self-critical?

Oh, hugely self-critical, but hopefully not to the extent that it becomes a problem. I think that’s a line that’s easy to cross and in the past I might have been micro concentrating on little details. You can get caught up in that but I think that’s part of learning, maturing and growing as a musician and a writer. Being able to step back and look at that.

As a band, you aren’t archetypal rock stars. How do you find other bands when you come across them at festivals?

Obviously there are people out there that define the real meaning of being a rock star. They’re eccentric or outspoken, march to the beat of their own drum or are just spectacles in everything they do. But I can say I’ve never met nicer people. I guess there’s that element of entertainment where you see some of these guys on stage and think, “That guy must be a psychopath, he’s probably drinking his own piss!” But no, he’s a really nice guy, more worried about the couple of pounds he’s gained on tour.

Do you still find it easy to get into the tour routine or is there a certain amount of dread that comes with playing live?

There are mixed feelings. With this current tour, we’ve been in the studio since January so I’ve constantly been thinking about the new album. We don’t usually tour in the middle of an album cycle so this is a little bit different. But at some point you have to commit when you realise in a couple of weeks you’ll be playing in front of all those people and you sure as hell better know the songs backwards.

Are you managing to lift weights and keep yourself fit when the band are out on tour?

Absolutely. Fitness is really important to me and weight training is a big part of my life. I try to get in the gym five or six days a week and being consistent with training while on the road is definitely a challenge. It takes discipline and determination. Generally the hotel gyms are okay but often I have to venture out into the city and find a local gym to get my workout in. At home it’s a lot easier.

How do you cope with the problem of jet lag? I remember hearing a story about you almost falling asleep on stage in Japan.

I didn’t literally fall asleep – I was just hamming it up! But that was extreme jet lag and that show happened shortly after we got there. It literally felt like it was three in the morning and someone has woken you up because the alarm is going off in the house. All of a sudden it hits you like a ton of bricks, and for some reason you’re awake and there are thousands of people in front of you. When you’re turned around by 14 hours or so, you can’t even picture yourself going on stage and playing.

**

It must be extremely difficult to be away from your family.**

That’s a big one and I wrote Endless Sacrifice [on 2003’s Train Of Thought] about that. The guys and I know we wouldn’t have been able to do this if it wasn’t for the incredible women we married. They work hard and make sacrifices too and our success is every bit theirs as well. It’s something we do together and if you look at all the months I’ve been away on tour, it’s a lot of time away. Everyone is happily married to the same women too, and I see it as something we all built together.

So when you do get home, what do you like to do in your spare time?

I really enjoy cooking using the barbecue and a smoker. Sterling Ball [bass designer and Music Man CEO] turned me on to it a few years ago and not only is it fun and creative, but it’s a good way to bring the family together and enjoy some great food. My wife and I are also really into enjoying amazing wines and there’s no better combination than great food and great wine. This past Christmas I did a full bone-in rib roast and it came out amazing. I posted some photos on my Facebook page if you want to see how delicious it looks.

I remember you saying after Mike Portnoy left in 2009 that Dream Theater never had a leader. Yet with all of the things you do now, surely that’s a role you fulfil?

Yeah, that’s true. The reality is that there have to be leaders. People have their own strengths in what they do. It’s important you recognise that and people are able to fulfil where their strengths lie. You’re right, but it’s really important to keep a certain perspective on things. Whether or not you’re the type of person who likes to be more involved or has a strong creative spirit or whatever, you have to do that in a way that facilitates all the qualities a band needs. You can’t do that in an autonomous or non‑inclusive fashion.

There’s a love that exists among band members because there are so many things you did together. All of a sudden that gets cut off and that person isn’t in your life any more. It’s definitely weird.

Is this something that’s changed over the last six years?

You know what, that’s a hard thing to say. I don’t want to say anything bad about the past or how things were done. Since Mike [Portnoy] left the band, I think I’ve risen to that in a much more fulfilling way. Mike was always someone who liked to take charge of that type of stuff, and constantly has a lot of ideas, opinions and energy and is a proactive person, as can be seen from what he has been doing away from Dream Theater. So without him in the band there has been more of an opportunity to do that.

Did you enjoy producing the band’s last two albums (2011’s A Dramatic Turn Of Events and 2013’s Dream Theater) by yourself?

Yes, and I have to say it has been great for me as I really love producing and it’s something I would love to do for other bands.

Looking back on that whole period when Mike left the band, do you wish certain things could have been done differently?

I don’t have any regrets. I think things happen for a reason and bands naturally evolve and sometimes that involves members leaving. I think in any situation like that, you’re looking back and I wish it could have been smoother, but in a lot of ways it was probably as smooth as that kind of thing could have been.

Surely there’s a sadness given that no matter what happened with the band, a friendship has been lost?

I know. There’s a brotherhood that happens in bands. Whether you have a strong or contentious relationship with someone, there’s a love that exists among band members because there are so many things you did together. All of a sudden that gets cut off and that person isn’t in your life any more. It’s definitely weird and it’s strange how that happens. I’m sure it happens in other businesses and careers where people have been together for a long time. It’s a natural part of life and isn’t something that’s easy to deal with. It’s a strange feeling.

As for the new album, you’ve been writing for a lot longer than normal, which suggests either writer’s block or a double album.

There’s certainly no writer’s block and there’s been no shortage of ideas. Without going into detail, this is a huge undertaking, what we’re doing. We’ve been working really hard and probably longer on this than other albums in the past. But you’ll see why.

Some fans suggested you played it too safe with the last two albums, whereas with Train Of Thought or Octavarium you took different approaches. Will this new album address those concerns?

Absolutely. This new album is definitely not like anything else we’ve done before. Sometimes you feel like you need to make a change and do something totally different like this, and that’s when the albums like the ones you mention come out. But those albums were also very polarising and a lot of people said they hated them at first. So you take a huge chance whenever you do anything like that, but it’s part of the growth of a band and is massively important to keeping things interesting and keeping the spirit alive, and keeping people engaged, ourselves engaged, and excited.

It’s not going to be a blues album, then?

No, it’s not a blues album! But we felt like we needed to do this, and that we needed to do something right now that is going to ground us. This album absolutely addresses that.

In the past, it’s been mentioned that if Dream Theater are unsure about something, you use the maxim: “What would Rush do?” Does that still hold true?

Ha, yes, it does in a lot of instances. Even for us, there are iconic bands out there who we still look up to, and we may try to emulate some of the decisions they would make. You could be sitting there, trying to make a decision, and think, “Hmm. Would Geddy do that?”