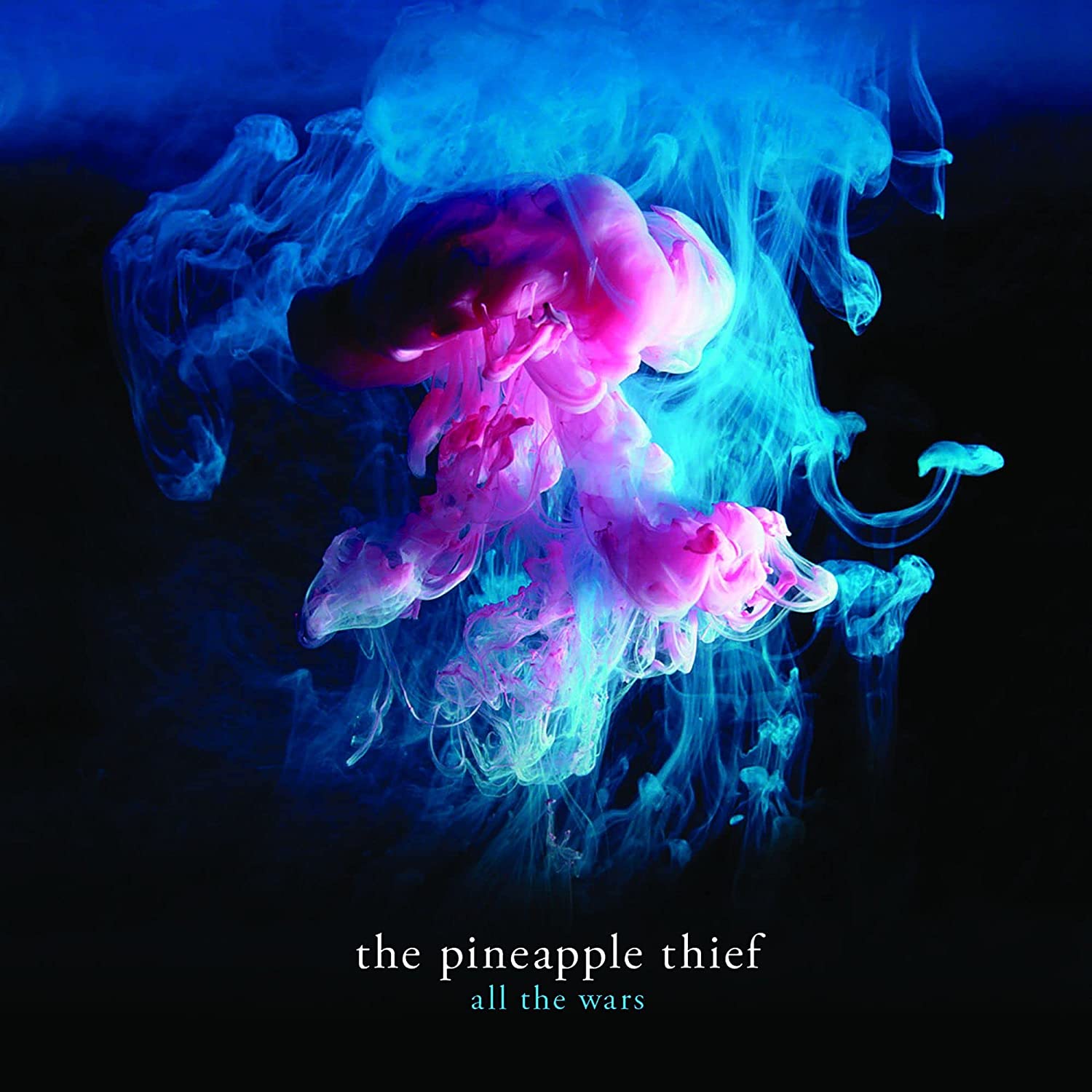

The Pineapple Thief and the making of All The Wars

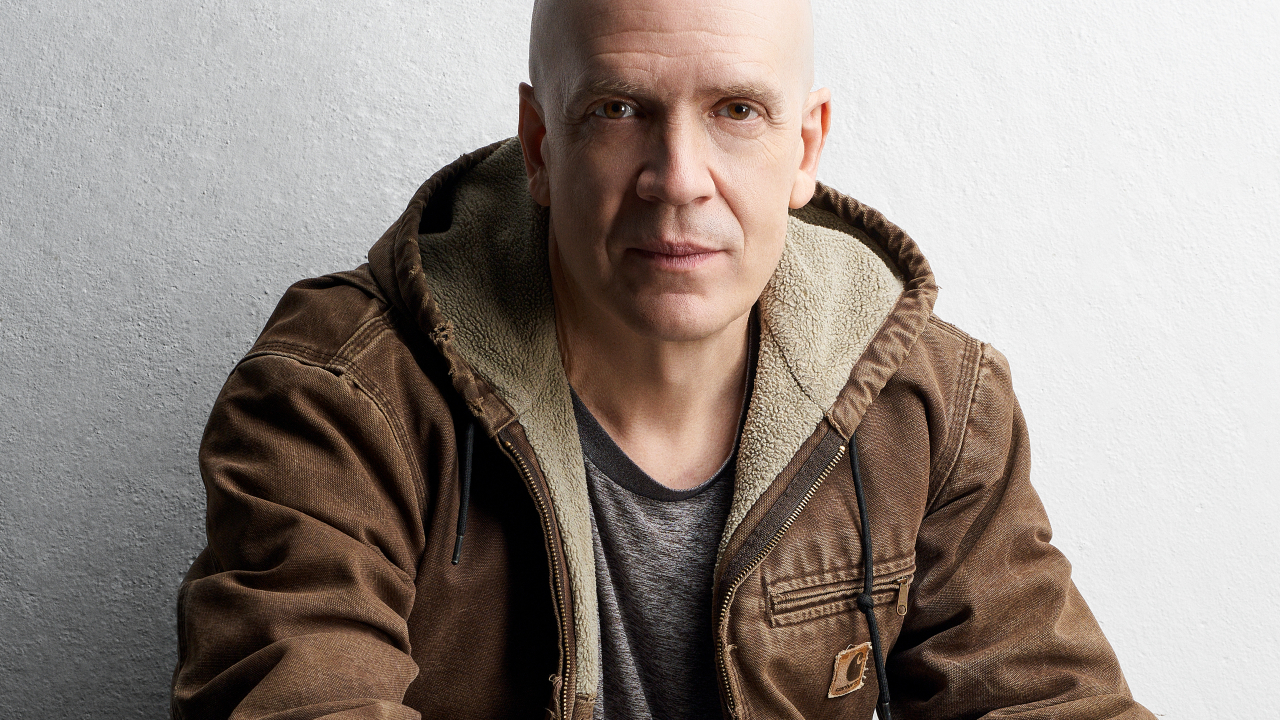

Bruce Soord discusses The Pineapple Thief's journey to making eighth album All The Wars

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It’s a lucky 13 years since the idea for The Pineapple Thief formed in Bruce Soord’s head. While many bands race out of the traps at the start of their career with their finest work – the one they spend the rest of their days trying to live up to – Soord has spent that time quietly honing his craft, getting better over time. And now he’s ready to unleash his band’s masterpiece, eighth album All The Wars.

While unmistakably progressive in its nature, from the soaring strings of the Prague Philharmonic to the weighty subject matter, All The Wars also bears a grungy, radio-friendly melodicism. This sees the band slot neatly alongside that scene’s more adventurous souls, particularly the Smashing Pumpkins, with whom Soord shares a beguiling, nasal vocal style.

The giant step forward they began with 2010’s acclaimed Someone Here Is Missing has been stylishly completed here, even if it took Soord 18 months of painstaking confinement to get there. “It was a real slog,” he admits. “But that’s only because I set the bar really high. I just basically had a shit filter from the very beginning. I’d work on an idea for a bit and if it didn’t work, I’d just put it in the bin and then wait for the next bit of inspiration to come along. So I knew it was going to take as long as it was going to take.”

Article continues belowBut, of course, the story stretches back much further. Bruce Soord was born in Germany, where his father was stationed in the army air corps. When he was two years old, the family moved to Somerset, and as the 1980s picked up momentum in a wave of bubblegum pop, young Bruce started to take notice of the songs on the radio’s Top 40 countdown, covering his bedroom walls with posters of Madonna and Howard Jones. And then, when he was 13, he met Neil Randall at school, the boy he’d go on to form his first band with and who would play a vital part in leading Soord down the prog path.

“I went round his dad’s house and he had this really, really posh stereo,” Soord remembers. “We sat around it and he played Tales Of Mystery And Imagination by The Alan Parsons Project, and that’s got loads of big string arrangements on it. It blew my mind – I’d never heard anything like it! All I’d listened to was throwaway pop, crappy Madonna songs, and all of a sudden I was listening to this whole new idea of what music was. Since then, me and Neil just had such a massive passion for music. We were those kids at school, the total nerds who would talk about nothing but music and wanting to start a band. And we did, we started a band together – it was terrible! But it was the start.”

From there until the time came to fly the nest for Leicester University, the boys would spend their time and money on day trips around the UK, scooping up armfuls of vinyl treasure from the bargain bins of the nation’s record shops. The positive side of being obsessed with music that wasn’t particularly cool at the time was being able to pick up gems for £1 a pop. Liverpool proved particularly fruitful, and they’d spend the long bus journey home poring over the 12-inch gatefold sleeves packed into straining plastic bags, imagining what clues the artwork gave to the music on the records inside. Bands like Pink Floyd, Supertramp and Yes, plus more underground figures such as Anthony Phillips, were revered. Later, in the 90s, the grungier sound of Faith No More, Soundgarden and Pearl Jam kept things fresh.

Soord’s most important youthful splurge was the £40 he spent on a nylon-string Spanish guitar – not that his parents understood the significance it would one day have for the budding musician.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I remember my dad saying, ‘What have you wasted your money on that for?’ Which was fair enough. He thought it was probably just another fad and I’d put it in the cupboard with my ham radio and my judo outfit. But I think when he said that, I was like, ‘That’s it, I’m not going to give up – I’m going to keep going.’ And it did take me a hell of a long time, because I didn’t have the faintest idea about music. I think it took me about a month to tune it up.”

More like-minded souls lay in the east though, and when he headed for Leicester at the age of 18, he quickly made friends with Jon Sykes, who’s now the bass player for The Pineapple Thief. They started a band together, finished university and headed to London, lured by the Camden circuit and the vague promise of fame and fortune.

Once arriving in the capital, it quickly became clear that the streets weren’t paved with the proverbial gold. There were, of course, hundreds of other bands vying for the attention of the A&R brigade, the venues were tiny fleapits, and promises of support from industry scenesters proved to be as empty as the band’s wallets. “I remember waking up and thinking, ‘This is just bollocks, I’ve had enough,’” says Soord. “And that’s when I started Pineapple Thief. It was something with no expectations that it would sell. I didn’t think anyone apart from my mates would hear it, let alone being here 12 years later still doing it. It’s amazing really.”

But that move back to the Somerset of his childhood proved, in retrospect, to be the best that he ever took. Locking himself away in a home studio, he started working alone on songs for the sake of the music, rather than chasing popularity. And, against all odds, people started to listen. His ‘unadulterated, undiluted vision’ spoke to a small label called Cyclops, who put out his debut album, Abducting The Unicorn. It took six months to sell 500 copies, but that was enough to get the ball rolling. To his surprise, Soord started gaining a bona fide fanbase.

“People started to ask for gigs and that’s how the band came together,” he says. “If you look at the journey that Steven Wilson had with Porcupine Tree, it’s a similar thing. He started it as a complete solo project as well.”

By 2004, demand was great enough that the inevitable next step was to get a full band together. Keith Harrison – whose prog claim to fame is that his uncle is Kerry Minnear, Gentle Giant’s classically trained keyboardist – came in on drums, alongside Sykes on bass. The original keyboard player departed because he couldn’t actually play keyboards. (“People were watching him and realising he was just pressing buttons,” laughs Soord. “He said it was just too embarrassing.”) Steve Kitch replaced him and the line-up has remained steady ever since. The only problem was that for the first couple of years they were, by their own admission, absolutely awful onstage.

“We had a very kind core fanbase, ’cos we did some pretty bad gigs but they still loved us,” says Soord. “We went all the way to the States and did this terrible gig and then we had to fly all the way home again. We just weren’t ready – we were rabbits in the headlights. It was awful. There was a moment a couple of years ago when we did a gig at the Half Moon in Putney and everything went wrong. In the dressing room after you’ve done a shit gig, it’s the worst feeling. Then you’ve got to get back in the van and drive all the way down to Yeovil. We all had a conversation and said, ‘Right, we’ve got to start taking this seriously.’ And we just sorted ourselves out.”

The final piece of the puzzle came in the shape of Kscope, the UK’s buzziest prog label, home to Porcupine Tree, Anathema and North Atlantic Oscillation. Suddenly, they were surrounded by the biggest names in modern prog – it was time to step up and join them.

All The Wars was written at a time of emotional intensity, and it shows. With its focus on growing older, the loss of loved ones and the need to make amends before it’s too late, it’s both deeply personal and entirely universal. “It’s not like I’ve gone through some hideous life,” says Soord. “It’s just the same things that happen to everyone. You start to lose people who you love, and more often than not, there’s going to be someone that you love who’s going to die tragically, or you’ll be estranged from someone. So it was witnessing that happen. My wife’s father died; he had a very slow and horrible death from cancer. Watching that happen, and the impact it had on everyone around him, it just made me think about love, life and death, the recurring theme through most of my albums.

“This album is called All The Wars because it’s about the conflict that we have with the people we love. That’s quite striking to me, because it’s only when someone dies that all of a sudden you look back and think, ‘Oh God, why did we have so much conflict and war with people that we love, and then it’s too late?’ Just talking about it is dark, but I always like to think there’s a cathartic, positive side. The songs are never without hope, I’d like to think.”

They’re certainly not without ambition either. After tracking drums at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios and then heading en masse to take up residency at The Chapel in Lincolnshire, they went to the Czech Republic to record with the Prague Philharmonic. The lush strings on the record were arranged by Andrew Skeet, orchestral wizard and keyboard player for The Divine Comedy.

“It’s not very rock‘n’roll,” says Soord, ”but when we did that, I was just sat in this room with 22 string players and it was so emotional I must confess I did tear up a bit. It was so intense and such a proud moment, because ever since I was a kid I dreamed of having a string section. I remember when I was young and I was going through record shops, sometimes I’d buy records purely because on the credits they’d have loads of string players. That’s what influenced me as I grew older, that classic 70s progressive use of strings.”

And with another dream ticked off, The Pineapple Thief are at a point where they can leap into prog’s pool of big hitters. The scene is the healthiest it’s been in years, with a passionate league of followers. It’s a secret society of millions, and Bruce Soord is ready to become one of its leaders. “There is a sense of belonging,” he notes. “When I was at college there was always a scene that you could be a part of. Now I’m looking at the kids and thinking they’re spread out so far that the new progressive scene is getting big enough in a cool little niche that people hook onto. It does feel really quite exciting.”

And there are a few people closer to home finally embracing The Pineapple Thief in all their glory – most importantly, Bruce Soord’s dear old dad, who was once so scornful of that £40 guitar. “It’s funny,” says Soord. “It’s only recently – ’cos bless him, he’s still not got a clue about music – but when I show him a magazine or our new album or photos from a gig, and he can see we’re not actually playing to 40 people in the local pub, we’re playing to 350 people in London, you can tell that he’s really proud. Every time I go round, if he’s got family or friends there, he always puts my albums on. It’s really embarrassing!”

This article originally appeared in issue 29 of Prog Magazine.

Emma has been writing about music for 25 years, and is a regular contributor to Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog and Louder. During that time her words have also appeared in publications including Kerrang!, Melody Maker, Select, The Blues Magazine and many more. She is also a professional pedant and grammar nerd and has worked as a copy editor on everything from film titles through to high-end property magazines. In her spare time, when not at gigs, you’ll find her at her local stables hanging out with a bunch of extremely characterful horses.