The Managers That Built Prog: Andy Farrow

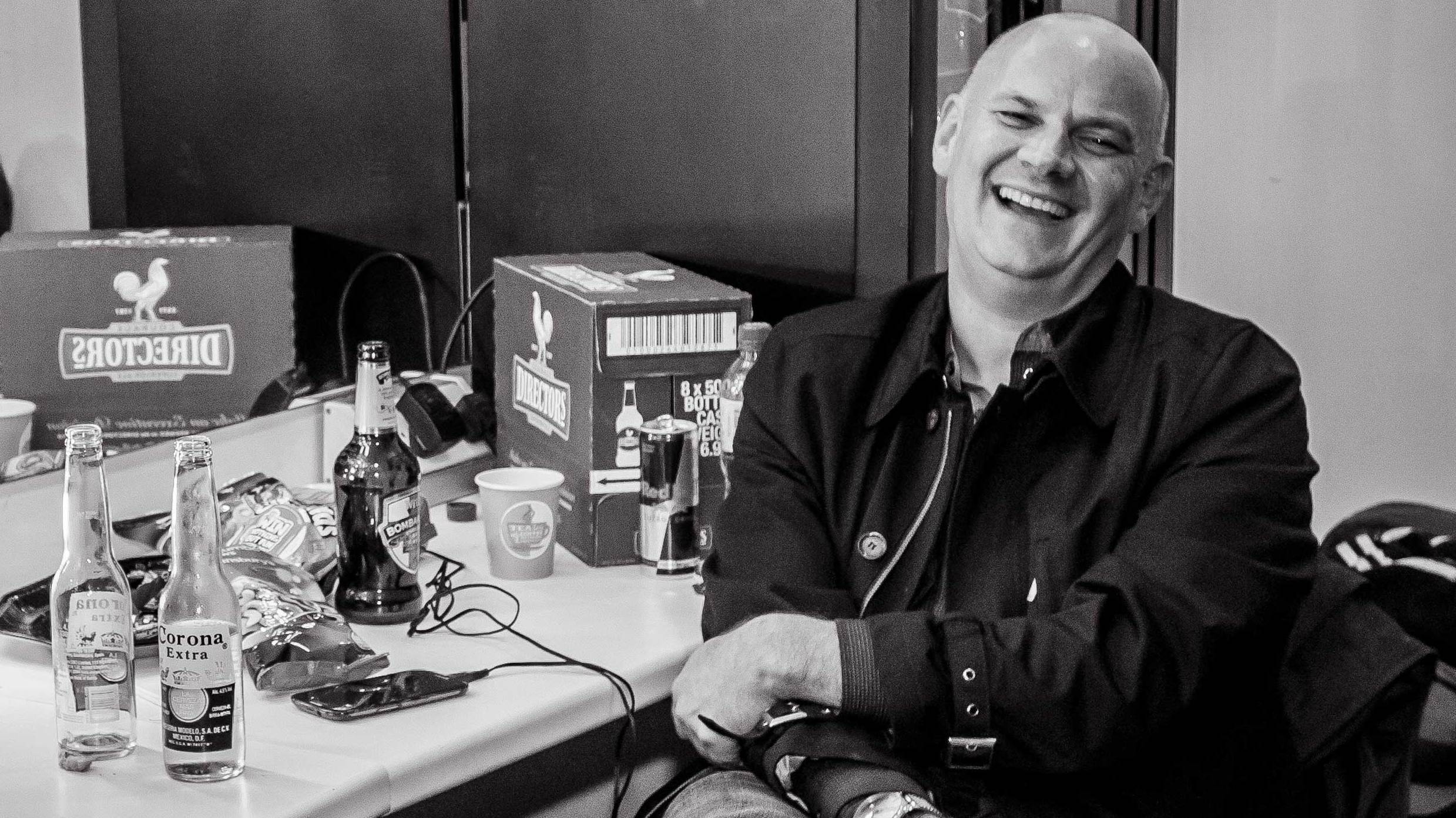

Cutting his teeth on punk, Andy Farrow has taken the DIY spirit of that genre into his work with progressive metal bands Opeth and Paradise Lost, thus redefining the role of the manager.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

From looking after Boneyard, who supported Manic Street Preachers on the Generation Terrorists tour, then got signed to Kitchenware before promptly imploding, Farrow met the band with whom he has enjoyed a long professional relationship.

“Paradise Lost had just released Gothic. I promoted a show in Bradford and they saw how well they did with merchandise. Their deal with Peaceville had come to an end, we had some talks and I went on and got them a few offers. In December, I’ll have been managing them for 25 of the 28 years they’ve been a band.

“They are an international band who understand the music industry these days. To earn a living, it’s very much about live and merchandising. You make a record that creates the hype and that’s the wheel that turns other income streams. Ironically, after managing them for 25 years, they have just got their second biggest record deal of their career, and a major publishing deal with Sony. This is an iconic band, very much a part of creating the gothic metal sound. I like to think a lot of my roster are leaders and not followers.”

Andy Farrow is one of today’s key players in prog and metal. He’s the epitome of a manager who lives and breathes his job, with a fervent belief in both his acts and the music they make. From starting young to looking after a handful of the most respected artists in their field – among them Paradise Lost, Katatonia, Devin Townsend, Anathema and Opeth – Farrow, and his company Northern Music, based in Saltaire in Yorkshire, is committed to establishing lasting careers for his performers.

For someone so renowned for metal and prog, however, Farrow’s roots are in punk. Returning to England in the summer of 1977 from Papua New Guinea, where he’d lived for two years as a child, he says, “I immediately got into punk. One of the first singles I bought was Promises by the Buzzcocks.”

His tastes were to expand from his diet of the Sex Pistols, The Stranglers and The Clash after seeing Motörhead on their Overkill tour when he was 14. “It was full of local bikers, The Satan’s Slaves. Motörhead were a band that it was okay for punks to be into. I morphed from punk into alternative, then into metal.”

Attendance at a local club, Griff’s Magic Theatre, exposed Farrow to Led Zeppelin, The Doors, Janis Joplin and Cream: “I went from being a punk to wearing necklaces and hippie-type gear. The sixth-formers at school were listening to progressive music and that influenced me too.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

With this open mind, the punk scene took Farrow into the music industry. “The whole anarcho-punk scene, with bands like Crass and Subhumans, enabled me to have a DIY attitude and get involved,” Farrow recalls. “I was in a band called The Living Dead. We weren’t that musical but because I used to do all the posters, flyering and the fanzines, we built up a pretty good following. I went from having my own band to managing Chronic, who were a cross between The Beatles and The Clash. At 16, I was ringing up pubs, getting them gigs.”

Later, Farrow set up a punk co-operative called Apathy Products and Crass played a benefit for them. “We used that money to put local bands into the studio to release the Apathy Compilation Tape, which we sold and tape-traded all over the world. I was still in sixth form at the time. I then went off to Sheffield Poly. I did a degree in case the way I wanted to go in the industry didn’t work out.”

However, Farrow was getting drawn to management. “It was a natural step for me, as I knew I didn’t want to be a frontman because I didn’t have the ability. I think my experience working in the underground and moving into signing bands gave me a reasonable amount of knowledge.”

By now there were plenty of tales of managers that had gone before in the business. “Peter Grant influenced me as he’d made a real difference to the way deals were done on the percentage of live income, merchandising, etc. It was a style of management that was a bit more gangster-ish and doesn’t go on now. Brian Epstein was clearly ahead of his time, yet when you look at The Beatles’ merchandising, there were big errors made. People didn’t know about that world then. [Iron Maiden manager] Rod Smallwood also influenced me.”

After completing his degree, Farrow formed Far North Music. At 22, he got thrash metal band Slammer signed to Warners. “At the time, Onslaught and Slammer got the major deals from the British thrash scene. It was quite an eye-opener because I had loads of labels after them. I even had the President of RCA America calling me saying they would better any advance we were offered.”

Sadly, Slammer were dropped after the first album, yet by today’s figures, they sold well. It proved a good experience for Farrow, and during that time, he decided that management was how he was going to make his living.

Farrow then looked after Loud, who signed to China, distributed by Polydor. “They did a couple of albums and supported Jane’s Addiction, Fields Of The Nephilim and Killing Joke,” he says. “Their second album was produced by Queen’s producer, [Reinhold] Mack, in Berlin. It was so far ahead of its time, they could have been compared to Muse. This made their audience wonder what they were doing and, like the bands I manage now, their music has changed over the years. I’ve always supported a band when they progress musically.”

Andy Black, MD of Music For Nations, told Farrow he had six bands that needed managing, one of them being Opeth. Noting the similarities to Paradise Lost, Farrow went to see them live. “Previously, the band hadn’t really toured. When I took them on, their feet didn’t touch the ground! They toured and toured. Their sales rose, as did their critical acclaim.”

It has been a long and lasting relationship. Farrow has had to deal with the frequently shifting line‑up of the band, and retains a strong relationship with their leader, Mikael Åkerfeldt. “The things I said I would get them, I delivered,” Farrow says. “I said I would get them the Royal Albert Hall and I did. They were the heaviest band to ever play there. I said they would play Wembley and they did. At first, it was part of ProgNation and now they’re headlining.

“I delivered because they’re not a band that are concerned with total commercial success – it’s more about a creative success. I’ve always marketed them to labels by saying, ‘You’ve got to see this band as today’s Led Zeppelin or Pink Floyd.’

“Managing Opeth is challenging at times, but every time I go to see them live, they never disappoint. It’s all about the music. Obviously the Opeth brand is powerful, and that has enabled us to do huge merchandising and also set up the company Omerch, which I own with the band. The idea of that is to be an artist-owned company. In the long term, it’ll be the band’s pension.”

Another act Farrow has nurtured is the genre-defying Devin Townsend. “I’ve managed Devin for the best part of a decade. I’ve marketed him as a Frank Zappa of this generation – you don’t always know musically where he fits in. I’m hoping I can make Devin into a much bigger star. He’s done The Retinal Circus at the Roundhouse, the Royal Albert Hall that sold out in four days without advertising, made acoustic albums, and now wants to do a symphony.

“He’s very hard to keep up with, but I’m hoping I can take him to greater success in terms of record sales. We’ve seen an upward swing on the last couple of records, particularly Epicloud. I want to see his record sales grow.”

Farrow remains thrilled with his roster. “Some of the songs Anathema are writing now are a long way from where they started – it’s very emotional music,” he notes. “And Katatonia are on an upward swing. I love their songs. Hopefully through touring they’re going to become a bigger band. Both acts have been going for a while and seen their record, ticket and merchandise sales rise.”

Although there have understandably been some misses in the past (Farrow passed on Million Dead singer Frank Turner when he went solo, despite having managed Million Dead, and he never made the journey to see Bullet For My Valentine), he is justifiably proud of his achievements and displays boundless energy for the future.

Nowadays, his companies fall under the Northern Music Group. With its 10-band roster (as well as producer Jens Bogren and graphic artist Travis Smith), Northern Music Co is Farrow’s management company. His empire also includes AMF Music Publishing, Graphite Records, worldwide booking division NMC Live and the aforementioned Omerch. He also has shares in Film24Productions; I Like Press, a Leeds-based PR company; and Versity Music, a management, production and rights company based in Stockholm.

“My latest venture is a shareholding in the Be Prog! My Friend Festival, based in Barcelona, which this year featured the likes of Opeth, Steven Wilson and Between The Buried & Me.”

So what advice would Farrow give to those starting out? “Well, there are various music industry degrees. I co-run my own course/webinar at www.howtomanagebands.com. Otherwise you learn day to day. If you’re a young manager and it starts to take off with your band, try to get a job with a management company so you have people you can talk to. Look for an internship within the industry or a management company, or if you have a band with a friend, try to go to a management company as soon as things start to happen.

“It’s all about knowledge: if you’re new, you only learn by experience. It’s very much about working in the field. You can learn stuff from a book but experience is everything.”

And, importantly for Farrow, the music has to matter. “Even if I think a band will make some money, I’ll only do it if I’m into it musically. I support the artist’s vision. Obviously, Opeth have changed their style and Devin takes various musical approaches. It’s a challenge, but what you have to do is take their piece of art, market it and support the artist in what they want to achieve.

“Something I recently found out after 30 years of doing this is that I have to like the band as people too. I’ve taken on some bands where it’s not worked out personality wise, because I’m definitely not a puppet manager and I will push to get my ideas through, which with some artists is a problem.

“Today you have to be a jack of all trades and know about every aspect of the music industry. I’ve been able to take bands that have come from the underground with a specific style and set them up as companies and made them a successful business that allows them to make a living. Not necessarily a great living, but I’ve set up a structure that allows them to be professional with artist-friendly deals.

“You have to make sure you own your masters later on, to have control of direct-to-fan sales, etc. Because in 10 years’ time, it’s all going to be about aggregating your fan base.”

Andy Farrow has updated the manager’s role for the 21st-century. Adapting with the times, he may not be the cigar-chomping barfly of old, but with his energy, creativity and love of music, he ensures the manager has an indispensable role going forward.

Daryl Easlea has contributed to Prog since its first edition, and has written cover features on Pink Floyd, Genesis, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel and Gentle Giant. After 20 years in music retail, when Daryl worked full-time at Record Collector, his broad tastes and knowledge led to him being deemed a ‘generalist.’ DJ, compere, and consultant to record companies, his books explore prog, populist African-American music and pop eccentrics. Currently writing Whatever Happened To Slade?, Daryl broadcasts Easlea Like A Sunday Morning on Ship Full Of Bombs, can be seen on Channel 5 talking about pop and hosts the M Means Music podcast.