The inside story of Marillion's Brave

In 1994, Marillion released their unsung masterpiece Brave. From its intriguing inspiration to recording in a chateau and the frictions that followed, the entire band look back on their great concept album of the 1990s

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Steve Hogarth never knew the name of ‘The Girl Who Didn’t Jump’. He can’t even remember when he first heard about her. It was sometime in the mid-80s, back when he was a member of How We Live.

Hogarth heard about her on a radio broadcast: how police had picked up a teenage girl who was wandering, lost and confused, on the Severn Bridge between England and Wales.

The bridge has been a suicide hotspot since it was opened in 1966, a magnet for troubled souls like the nameless girl. She refused to give her name, refused to even talk. Police appealed for information on the radio and TV, which is when Hogarth heard about her. It struck a chord with him.

“I thought, ‘That sounds like the first page of a mystery novel,’” he recalls. “I scribbled it down and forgot about it.”

But he didn’t, not quite. The story of The Girl Who Didn’t Jump stayed deep in Hogarth’s mind, floating just below the waves of his subconsciousness, not surfacing but not sinking either.

It was sometime in 1992 when Hogarth thought about her properly again. By then he was the singer with Marillion, the band he had joined a few years earlier. It was while Marillion were writing songs for a new album that Hogarth told his bandmates the story of The Girl Who Didn’t Jump – a story that would become the beating heart of the record.

The album they built around it, Brave, would turn out to be the most pivotal of their career. It would determine their future – or whether they even had one. It finally brought them together as a band while irrevocably damaging their relationship with their long‑time label, EMI, and pushing away a whole swathe of their fan base. It ultimately set them on a tumultuous, frequently painful path that brought them to where they are today.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

But if Brave seemed at the time like a huge gamble that backfired massively, today it stands as the great concept album of the 1990s and an unsung masterpiece. In an era when idiots ruled, it was a beacon of intelligence and depth.

The story of the girl on the Severn Bridge could be read as a metaphor for Marillion, only in reverse. The girl never jumped, but Marillion did.

“Brave was the point where the pieces of the jigsaw came together,” says Hogarth. “We became this other band, with me in it. We became the band we are now.”

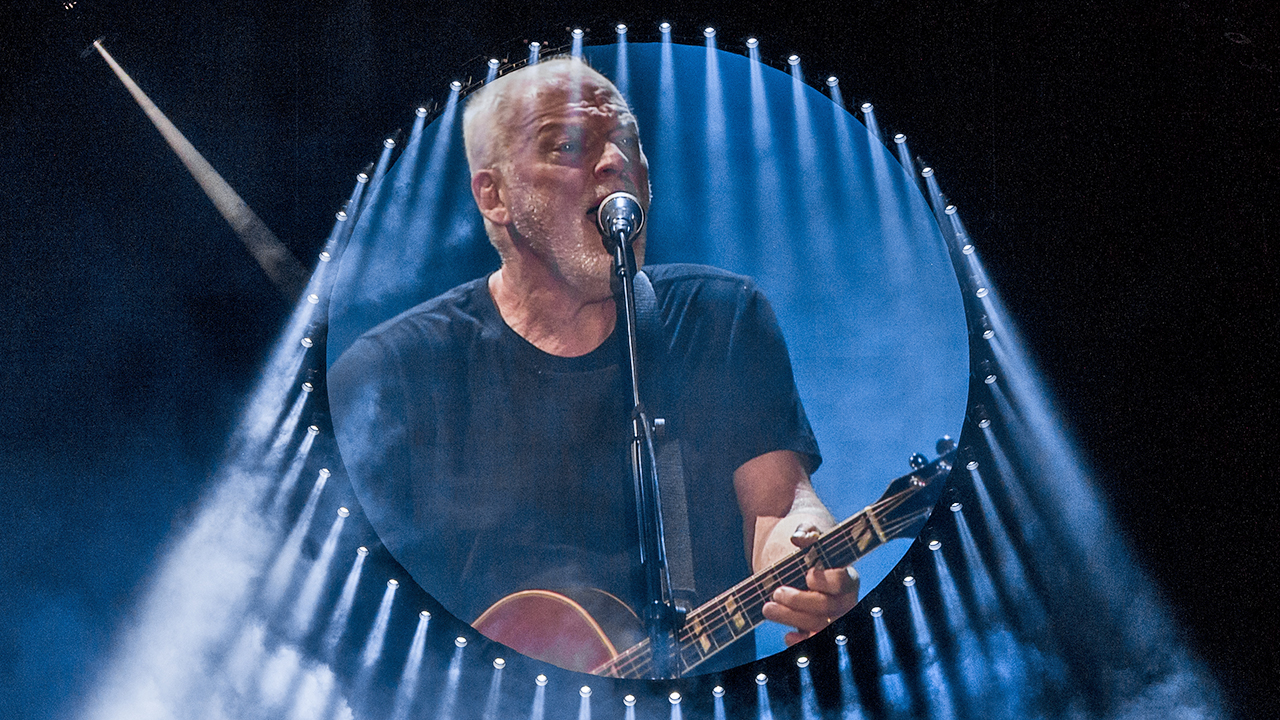

Marillion released Brave in 1994, but it remains fresh in their minds. Today, this is mainly because The Racket Club, their base/studio/lair on the outskirts of Aylesbury, is bustling with a team of people packing special vinyl editions of the brand new deluxe vinyl reissue of the album into large envelopes, ready to send out. Hogarth, keyboard player Mark Kelly and drummer Ian Mosley take turns to troop upstairs to the band’s office to look back on the album. Guitarist Steve Rothery and bassist Peter Trewavas reminisce over the phone and Skype respectively – both are out of the country, the former playing a solo gig in Copenhagen, the latter working on a mystery project in Baltimore in the US. “You’ll find out about it in due course,” he says enigmatically.

Fittingly, it’s here that Brave began to take shape a quarter of a century ago – or at least nearby, in another unit a few doors down, home of the original Racket Club. “I remember me and Steve H would go there when nobody was around and have these little night sessions,” says Kelly. “And the opening part of the album came in one of those night sessions.”

To get to the heart of the album that would change Marillion’s career, you have to understand what came before. Hogarth joined in 1989, after the departure of original singer Fish. This new partnership hit the ground running with 1989’s Season’s End, the first album they made with Hogarth. It was partly an act of defiance.

“A lot of people expected us to fail without Fish,” says Kelly. “But we were all very excited to be working together and it was all very quick. But we didn’t really stop to take stock and think, ‘What sort of band do we want to be now?’”

If they didn’t know themselves, their label, EMI, had a good idea. They figured that Hogarth’s background in poppier acts like The Europeans and How We Live would help push this sometimes complex band towards the musical middle ground. “If you liked Marillion, you didn’t really own up to it,” says Ian Mosley, wryly. “It was like something terrible had happened to you.”

For their next album, Holidays In Eden, EMI hooked Marillion up with Mike And The Mechanics producer Chris Neil.

“The record company were very excited about Steve and having a more commercial voice in place,” says Pete Trewavas. “They were thinking of Mike And The Mechanics and hitsville.”

Churning out hit singles to order was, of course, easier said than done. As the rush of excitement that had fuelled Seasons End began to wear off, the gulf between the two constituent parts of Marillion was becoming increasingly evident.

“With Holidays In Eden, we started it with a blank slate, then suddenly we were confronted with this problem that H liked to work quickly and wanted to write a song a day, and we were like, ‘You’ve got to let it mature, leave it six months, come back to it, see if you still like it,’” says Kelly.

“It was absurd,” laughs Hogarth.

The different modus operandi caused friction. At one point, the singer was even sent home from the residential studio while the band worked on the music. “It did create some tension,” says Kelly. “It still felt like us four and him really not quite gelling.”

Holidays In Eden didn’t quite turn Marillion into the new Mike And The Mechanics. The album reached No.7 in the UK charts, though it faded fast. It never reached the crossover audience their label hoped for, while the band’s hardcore fans were suspicious of its glossier approach.

“I suppose you could say it was a bit of a ‘Marillion-lite’ album in some respects,” says Pete Trewavas.

More than a decade into their career, Marillion had learned a valuable lesson. “There was sense that we tried doing it EMI’s way, we tried making a commercial record, and it didn’t really work,” says Steve Rothery. “So let’s just do what we love – it’ll either sell or it won’t sell, but at least we’ll be artistically satisfied.”

Their next move would be to go in the exact opposite direction. If Holidays In Eden was quick, gleaming and ultimately a compromise of sorts, Brave was anything but.

Between Holidays In Eden and Brave, several significant things changed in Marillion’s world. Some of those things were in their control, others weren’t. One key decision they made was to fit out the original Racket Club with new equipment, using their advance for the next album.

“The label were really against it,” says Kelly. “But we said, ‘We can use it for multiple albums,’ which was a really good move. It basically set us up for when we later got dropped by EMI.”

It was there that the band started writing the new album. It felt like a chance for them to properly start working together after the false start of Holidays In Eden. “The feeling changed, the surroundings of what we were doing became a little earthier and not so glamorous,” says Hogarth. “That might have rubbed off.”

But something else had changed – something out of their hands. Marillion had been assigned a new A&R man, a young hotshot named Nick Mander. In the band’s telling, Mander wanted them to adopt a different approach to making the album.

Hogarth reveals: “Nick Mander said, ‘I’ve promised the boys upstairs there’s not going to be any of this long, sprawling, big budget, contemplating your navel for six months stuff – we’re going to get a producer in who is much more indie and down with the kids, we’re going to make a fast, rough, raw album.’ I was up for it. But, of course, I’m the one who likes to work quickly. They were all [worriedly]: ‘Ooh…’”

“We thought it was nuts,” says Trewavas. “We thought the poor chap was being hung out to dry. Being told to get Marillion to do something quick and snappy? We’re clearly not capable of that. We thought, ‘He’s having a laugh. Does he realise what we do and how we do it?’”

Mander’s first decision was to introduce the band to Dave Meegan, who had recently worked with fleetingly successful Manchester indie group The Milltown Brothers. He was unaware that Meegan already had a relationship with Marillion – he had been a young tape operator at Sarm East Studios in London, when they recorded Fugazi a decade earlier.

“It was a different band and it wasn’t,” says Meegan today. “Obviously, Steve’s a very different person to Fish, but the methodology of the band was the same.”

That methodology chimed with Meegan’s own. He learnt his trade working for Trevor Horn, and the Yes/Buggles producer’s meticulousness had rubbed off.

“We like to work slowly and explore all the alternatives and ponder the music and do a lot of chin-scratching and nodding of heads,” says Trewavas. “And Dave was exactly the same: ‘This is interesting, let’s see where it takes us…’ And between us, we just thought, ‘We’ll take as long as we want.’ And we did.”

The third thing that happened that changed the course of Brave, and by extension Marillion’s career, was that they were suddenly presented with the opportunity of recording in an honest-to-God chateau in the south of France. The castle, located in Marouatte in the Dordogne region, belonged to Miles Copeland, head of the band’s US label IRS and brother of Police drummer Stewart Copeland.

“We liked that idea,” says Hogarth. “‘Yeah, let’s find a house cos it’ll keep the costs down. We’ll get something with a vibe and go and work there.’ We all thought it would make for an interesting record and an adventure.”

And so, in February 1993, Marillion and their equipment found themselves en route to the south of France to start work on their “fast, rough, raw” new album.

“I drove down there with Mark through the night,” recalls Rothery. “We got there just after the dawn. You see it up on the hill, and it’s a Hammer horror house basically.”

Meegan set up the band’s equipment in the large, gothic living room, and his control at the other end of the chateau, in the master bedroom. “The big four‑poster bed was still in there,” he says, “so I put all my stuff around it.”

They weren’t going into the sessions cold. They had riffs and chords for the songs that would become The Great Escape and Hard As Love, worked up back in Aylesbury. Rothery had written the intro to the album’s closing track, Made Again, for his newborn daughter.

“Brave was the first album we’d actually written between the five of us,” says Rothery. “It was the first time we had to knuckle down. And because it was a concept album, the rest of us found it easy to get our heads around what we were trying to do with it.”

It was Hogarth who came up with the idea of making Brave a concept album. “I’d got a song that became Living With The Big Lie about what human beings are capable of getting used to. We’re hardwired to get used to anything, no matter how obscene – it’ll shock us again the second time, then the third time it’s just how things are,” he says. “That took me back to the girl on the bridge and the radio broadcast.”

Hogarth floated the suggestion past his bandmates. “And they all jumped on that as though I’d laid them out a clotted cream tea: ‘We’ll have some of that!’” he says.

Marillion had been here before. Their last fully fledged concept album, 1985’s Misplaced Childhood, was their biggest hit and had rescued their career. But if the idea of a concept album had been uncool back then, it seemed positively suicidal now.

“Oh yeah,” says Hogarth. “But we didn’t give a fuck. We learned ages ago that not caring about those things was the way forward.”

They quickly fell into an efficient work pattern: breakfast, a morning of work, break for lunch, return to work, eat, maybe have a few wines and then continue working in the evening. Ian Mosley’s drums were the first thing to be recorded.

“We spent quite a while getting the drum sound and experimenting,” says Mosley. “Dave really did like experimenting, sometimes to the point where I thought, ‘I’m not going to play this one any better.’”

“Dave started editing drums, and just carried on,” says Rothery. “For days and days and days and days. We just sat around going, ‘What’s he doing? Is he losing the plot?’”

The days turned into weeks, and the weeks began to stretch out. By the second month, the band were starting to get antsy. They called a meeting with Meegan in the chateau’s dining area.

“We said to Dave, ‘Can we have a chat?’” says Hogarth. “We said, “We’re all a bit worried about how long it’s taking, Dave.’ And he said, “Well, the way I see it, we can either make a record or we can make a masterpiece. And I think this could be it. So you tell me what you want me to do.’ And we all went, ‘Let’s make a masterpiece,’ and that was the end of it.”

As Meegan and the band worked, the songs began to take focus, as did the overarching concept – not so much a straightforward narrative about the girl on the bridge as a series of snapshots that showed how she got there. According to Hogarth, many of the lyrics featured thinly disguised autobiographical elements: Living With The Big Lie, Brave itself, and especially The Hollow Man.

“The Hollow Man was a piece of confession about where I was at, personally,” says Hogarth. “I was coming unhinged. I was becoming increasingly shiny and Jean Paul Gaultier-clad on the outside, and lost inside. My wife used to find me fetal on the lounge floor sometimes when she came in. It was touring, trying to be the father of two small kids and not being cut out for it, or so I felt; being in love with too many people and too many things. And just trying to balance all that and deliver some kind of amazing piece of work that would revive the band’s fortunes.”

Not all of the songs fitted the concept. The pulsing hard rock of Paper Lies, included at Meegan’s insistence to give the album’s otherwise moody musical flow a kick, was originally inspired by the death of crooked newspaper tycoon Robert Maxwell and was only retrospectively crowbarred into the existing narrative. In a nod to the song’s subject, who died in mysterious circumstances after falling from his yacht, it ends with an enormous splash – something the band recorded by throwing a boulder from a home-made raft inside a cave near the chateau. This level of detail was admirable, but it didn’t impress the band’s paymasters at EMI. Not that Marillion themselves were concerned.

“We weren’t bothered by the fact that Nick Mander was starting to come unhinged by the fact we hadn’t done very much,” says Kelly. “As long as we didn’t get the plug pulled on us, which we didn’t think we would.”

They spent three months in Marouatte in total – more than enough time to make a record. But Marillion and Meegan were nowhere near finished. In the summer, they decamped to Liverpool’s Parr Street Studio to continue recording. Down in London, EMI were getting increasingly frantic about the length of time it was taking to make this ‘rough, ready, quick’ album.

Relations were becoming increasingly strained. The band say that Nick Mander blew his top when they bought a £30 coffee machine. Another time, Hogarth told the label that he needed a week off.

“I was either going to go on this family holiday or get divorced, which was perfectly reasonable on my wife’s part,” says Hogarth. “And it was like, ‘EMI have gone nuts. They say you can’t.’ So I got on a train and went to London to see the head of A&R face-to-face and say, ‘I know you think we’re all just sitting on sun loungers, but we’re working very hard and making a great record.’”

Hogarth got his holiday, but EMI refused to ease the pressure. They wanted a Marillion album, and they wanted it as soon as possible.

“Their theory was that it was still going to be finished sooner with pressure than it would have without,” says Meegan. “But that sort of album, you should be feeling pressure and tension – that’s what’s most of it’s about.”

Marillion spent another four months in Parr Street on top of the three months they’d spent in Marouatte. Neither the band nor Meegan say they were concerned about the album ever spinning out of their control, but Mark Kelly admits that the occasional nagging doubt crept in.

“We got to the end of it and I remember thinking, ‘What if it’s shit? What if no one likes it?’” he says. “When you get that far into it, it’s possible that there might come a point where you’re just not willing to admit that it’s terrible, because of the time you’ve invested in it.”

“We didn’t know, even when it was finished, what it was,” says Hogarth. “I remember feeling very nervous listening to the mixes. Being excited but at the same time thinking, ‘This sort of sounds like Quadrophenia or something. I don’t know what people are going to make of it.’”

There were other storm clouds gathering on the horizon. EMI were distinctly unimpressed by the length of time it had taken Marillion to make Brave. The “fast, rough, raw” album had come several months late, and certainly not cheaply.

“By the time we got to the end of that seven months, the writing was on the wall regarding our relationship with the label,” says Rothery. “We’d made a fantastic record and we had to hope that it was going to be successful enough to justify this huge expense and the damaging of our relationship with the label.”

Still, EMI weren’t so pissed off that they didn’t plan a big release party for the album at the London Planetarium. The idea was to invite assorted journalists and radio executives along without telling them who it was they were listening to.

“That was a big fuck up by EMI,” says Kelly. “They basically tried to make people believe it was a new Pink Floyd album, which was a huge mistake – they thought if they did that then more people would come along to the playback. But of course people came along and went, ‘What the fuck’s this? This isn’t Pink Floyd!’”

For a group who had long been critical whipping boys, Brave was surprisingly well received. Q magazine praised the album, calling it “dark and impenetrable”. Hogarth beams at the description. “I liked that. That’s a compliment.”

But “dark and impenetrable” doesn’t traditionally equate to commercial gold. Brave scraped into the UK Top 10 by the skin of its teeth – their lowest-charting album to date. The first single, The Hollow Man, reached No.30. The follow-up, the snappy Alone Again In The Lap Of Luxury, didn’t even make the Top 50.

In fairness, Marillion’s timing was lousy. Brave was released just as the nascent Britpop movement began to take shape. A 70-minute concept album about a suicidal girl was always going to struggle next to Blur or Oasis. But it was more than just the nation’s pop kids that Marillion failed to entice. The album left sections of their own fan base cold.

“We knew it wasn’t immediate,” says Trewavas. “We just hoped that people would give it the time of day and allow it to grow on them.”

If Brave started to separate out the fair‑weather fans from the diehards, then the tour finished the job. The band elected to play the album from start to finish, with Hogarth acting out characters from the songs in time‑honoured Peter Gabriel fashion. At one point, this involved tying his hair into pigtails and putting on lipstick to play the girl herself. It was a deliberate challenge: are you with us on this journey?

“The atmosphere in the concert halls was, like, ‘Fucking hell, what’s all this?’” says Mosley. “When we came on and did the encore and played songs that weren’t from Brave, it was a completely different show. You could physically see people sigh with relief.”

Neither the tour nor the album did much to build Marillion’s audience – or even retain it. Brave sold around 300,000 copies – good numbers today, but less than half of what Seasons End had sold five years earlier. “It was certainly a step down from where we’d been before, sales-wise,” says Kelly.

Brave’s protracted gestation, coupled with its apparent lack of success, was noticed at the top at their label. EMI’s European boss, Jean-François Cecillon, called a meeting with the band.

“He said, ‘I need you to give me a single on your next album or that’s it,’” says Kelly. “His exact words: ‘I want Cry Me A River.’ We came up with Beautiful, which was the closest thing to a single we had. But I’m not sure we were the right band at that time to be having hit singles.”

They may not have been able to write hits to order, but Marillion conceded that they should at least think about working faster on their next album. That record, Afraid Of Sunlight, came out just over a year after Brave. But it was too little, too late. As they suspected, the writing was already on the wall. The label dropped them soon after.

“We just went back to being the band the media hated,” says Kelly. “As far as the mainstream music press was concerned, we didn’t deserve to live. It was business as usual.”

What happened next to Marillion is a story in itself: how a disastrous deal with independent label Castle saw their stock plummet to rock bottom, how they hit on the idea of crowdfunding a US tour and the subsequent Anoraknophobia album, how they created a brand new business model that didn’t just secure their survival but sustains them – and so many other bands – to this day.

But Brave has its own story too. This “dark and impenetrable” record proved a tough sell at the time, but it has taken on an afterlife of its own. They have revisited it twice during the past 20 years, playing it in full in 2003 and again in 2011.

“We lost a lot of fans on Brave,” says Hogarth. “It wasn’t well received. Everybody now looks back and goes, ‘What a great album.’ But nobody was saying that the day it came out.”

“I think it needed at least a year or two after its release before people saw it for what it was,” says Rothery. “It’s definitely us going, ‘This is what we do, this is who we are – we hope you like it, but this is the course we’re committed to.’”

One of the reasons for its longevity is musical: its careful pacing, its shifting moods, the attention to detail that saw them recording the sound of rocks splashing into water in caves in the south of France. But it also represents something else: this was the ultimate underdog record by the ultimate underdog band.

“People that listened to us are willing to invest the time,” says Mark Kelly. “They’re willing to go, ‘Oh, I didn’t really get that, I’m going to give it another listen,’ rather than ‘I didn’t really get that, I’m going to move onto the next thing.’”

If Brave’s impact seemed negligible at the time, today it feels like a landmark. It proved that there was still space for intelligent, intricate conceptual music in the charts. You can trace a line from it to Radiohead’s OK Computer (released just three years later) and on to Anathema’s masterful The Optimist, which unconsciously echoes Brave’s psychogeographical journey to Marillion’s own F.E.A.R., an album which shares so many characteristics with Brave.

“We aren’t here to play nice shiny music that you can hear anywhere,” says Pete Trewavas. “We’re here to do something different and shake a few trees and make people think. Hopefully we did and hopefully we still do.”

And what about the girl on the bridge who inspired the album, The Girl Who Didn’t Jump? Steve Hogarth remembers reading that her parents came and collected her and took her back to the West Country. “I think they all lived reasonably happily ever after,” he says, but he doesn’t know anything beyond that. He suspects they might know about the album, though they’ve never been in touch. Why would they? Brave was a heavily fictionalised version of a turbulent event, and not the sort of thing they’d want to stir memories of.

But Marillion did jump, and it would eventually be the remaking of them. Their dark masterpiece started off a chain of events – some of them painful, some of them not – that culminated in their eventual rebirth.

“It was us putting two fingers up to the music business,” says Steve Rothery. “That came back to bite us on the backside, but it also allowed us to chart a course of our own making. It was responsible for our subsequent path and the whole crowdfunding thing and the reinvention of how a band can work. And that’s why we’re still here.”

This article was originally published in Prog 87.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.