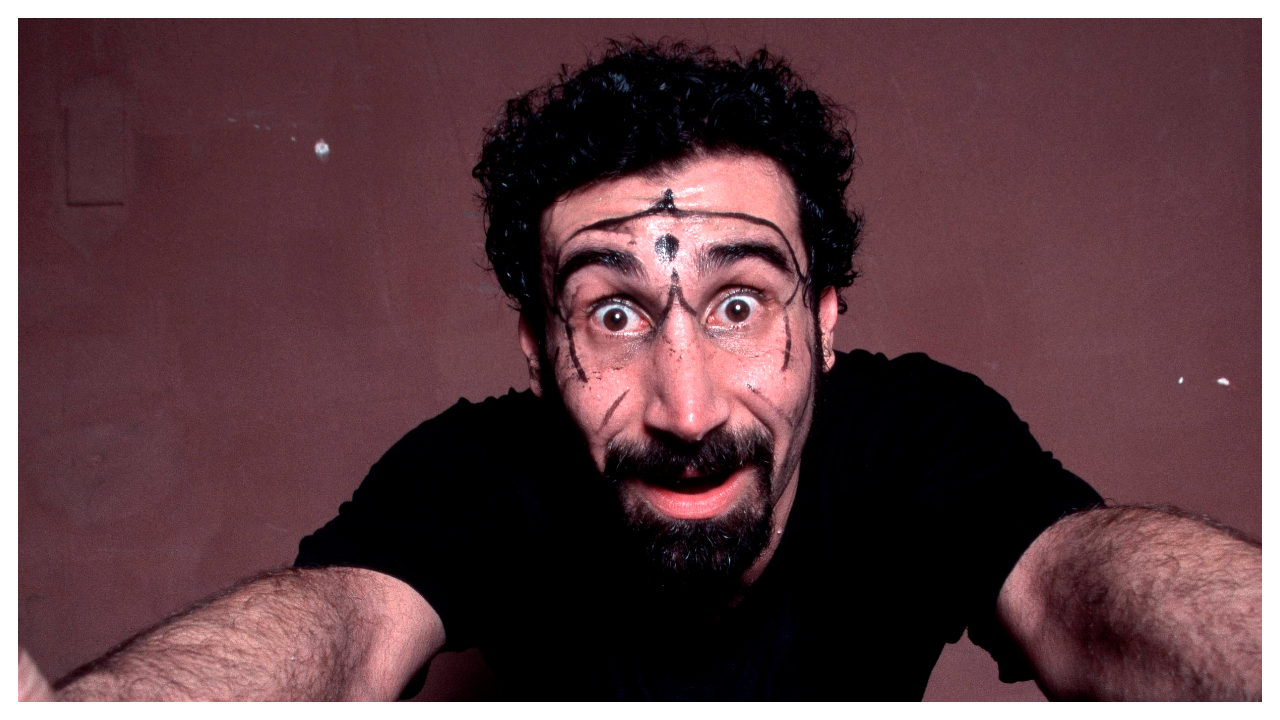

“We inadvertently started an LA riot, and we didn’t even do anything." System Of A Down frontman Serj Tankian on fleeing civil war in Lebanon, causing mayhem in Hollywood and becoming an unlikely metal icon

From hearing bombs drop around his childhood home to fronting one of metal's biggest ever bands, this is Serj Tankians unbelievable life story

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It was late at night and pouring with rain when Serj Tankian had what he calls his “epiphany”. Serj was in his mid-20s and had been working for his uncle’s jewellery business since graduating from university, playing music on the side. But he wasn’t happy, so he had decided to study to become a lawyer.

He was making the long drive from Downtown LA to night school in Long Beach when his subconscious took over. He slammed on his brakes and started hitting the dashboard, yelling: “I want to do fucking music, fuck all this shit.”

“Becoming a lawyer was a very negative thing,” Serj told Metal Hammer in 2021. “I fucking hated lawyers. But I always say that I had to go to the far extreme of who I shouldn’t be to shake myself into the realisation of who I am.”

His roadside meltdown was a tipping point. Within a few months, he had joined a young Armenian-American metal band named Soil, who would eventually mutate into System Of A Down. More than a quarter of a century on, the 55-year-old is one of modern metal’s most charismatic figures, a multi-hyphenate singer/artist/activist whose career has been punctuated by both political controversy and ongoing intra-band drama with the rest of System.

“This is what I’ve learned as an activist within the music world,” he explained, as he prepared to look back over his life. “It’s very easy to be truthful when public opinion is on your side. It’s incredibly difficult to be truthful when it’s not.”

You were born in Beirut, Lebanon in 1967. What’s your earliest memory?

“I guess my earliest memory would probably be my grandparents’ house, which was down the street from our house. Them looking after me, as families do. The stairs leading up to the street, the beach, the first time I went to the beach…”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Civil war broke out in Lebanon in 1975. You’ve talked about hearing bombs dropping. What was that like as a young kid?

“At that age, it’s really hard to process. I could only make sense of it as an adult. I have a six-year-old right now, and he plays with little toy planes and jet fighters. He says, ‘Why are they called jet ‘fighters’, why are they different from the other planes?’ And I say, ‘Oh, because they’re used in war.’ And he’s, like, ‘What’s war?’ That just floors me. How am I going to explain war to a six- year old? Because war is so illogical.”

Your family left Beirut for the US soon after. What are your first memories of America?

“Ha ha! American cheese. It’s so yellow. And bell bottom jeans – it was 1975, man. It was a culture shock, going from Beirut, Lebanon to Hollywood, California. It was a completely different language. I knew a little English, but it took me a year or so to catch up.”

When was your sense of injustice instilled in you?

“It was at quite a young age, my early teens. It was the realisation of living in a democracy like the United States, which had tabooed the recognition of the [Armenian] genocide for political expediency and economic reasons, because Turkey was a NATO ally. It made me extremely cognisant of the fact that there are so many truths out there that are being undermined and traded for other nefarious purposes. That made me an activist.”

What was the worst job you had growing up?

“I’ve done many things. I worked in the shoe-manufacturing business with my dad, I sold shoes, I worked in the jewellery business with my uncle, I’ve owned my own software company. Maybe shoe sales wasn’t the best job, but I was a teenager working in a little mall and there were lots of beautiful girls there. But if I ever went back to my past, I wouldn’t change anything – every single experience made me who I am. How can I regret anything?”

You started out as a keyboard player in the band Forever Young, before becoming an incredibly distinctive singer. Where did you find your crazy?

“I must’ve found my crazy in Soil, even before System Of A Down. It was such crazy, heavy, progressive music that it kind of unlocked something within me in terms of expression. But by no means was I a great singer at all. I was just expressing myself, screaming half the time and trying to sing half the time. I didn’t even know what I had to say, but it came.”

Was it tough getting System Of A Down off the ground?

“It was hard work. A lot of labels were very reticent in signing us: ‘Who’s going to play this music on the radio?’ We never thought about it. We just made the music that we made, ’cos that’s what you do as an artist. We were touring endlessly for the first few years. I don’t remember being home. But it was more fun for me. Any time you’re working your vision and you’re in the right place at the right time, it’s going to be fun. ’Cos the universe is conspiring with you, right?”

You had Rick Rubin in your corner early on. What do you recall about making your first album with him?

“I remember Rick’s idea was, ‘You guys are so crazy onstage in terms of sound and dynamics, I just want to record it as it is, as live as possible.’ That first record definitely makes you feel like you’re at a live show. And we worked with [Tool producer] Sylvia Massy, who was our engineer at the time. We had a star team. We were in amazing hands.”

You were due to play a free show in a Hollywood parking lot the day before your second album, Toxicity, came out, but it ended in a riot. What was that like?

“We were so stressed. We expected 3-4,000 people and 15-20,000 showed up. We were at a club across the street, where we were going to prep to play. And they came to us and said, ‘The Fire Marshal is not allowing the show to happen because the barricades have broken. They’re gonna close the show.’

“We tried to convince the police to let us go play, even if it was just a few songs to calm everyone down. They said, ‘Absolutely not’ and threatened to arrest any of us trying to make it to the stage. I got the guys together and went, ‘Fuck ’em, let’s go and do this, let them arrest us. Who cares?’ And my lawyer grabbed me and said, ‘This is LA, they will sue the fuck out of your band, take everything you have.’ I was thinking, ‘I’m doing fucking music, this is not how it should be.’ I mean, shit, we inadvertently started an LA riot, and we didn’t even do anything.”

Toxicity was at No.1 when 9/11 happened. A few days later, you posted an essay on System Of A Down’s website called Understanding Oil, which looked at the reasons why the attacks happened. You got death threats for being ‘unpatriotic’…

“It really backfired. It wasn’t just death threats. They were talking shit about what I had said on The Howard Stern Show, mischaracterising my words and intentions, so I had to get on and defend myself. This was right at the beginning of our tour – we were on the news on a daily basis, there’s terrorist threats all over the nation, we’re playing in front of 20,000 people a night. Are we safe? Are they safe?

“I remember John [Dolmayan, System drummer] asking me, ‘You’re a smart guy, what the fuck are you doing? Are you trying to get us killed?’ That’s literally what he told me. I felt so bad. I love these guys and here I am touring with them, and I’m like, ‘I’m so sorry – it’s the truth, I swear it’s the truth.’”

You’ve been a vocal critical about the Turkish government’s refusal to acknowledge the Armenian genocide. In the Truth To Power documentary, you claim there was a Turkish intelligence plot to assassinate you. Really?

“We had a protest in front of [then- US speaker] Dennis Hastert’s office, and my security detail had a few friends in the FBI. They basically told him that they were looking into Turkish intelligence interests ‘looking at your client’. I don’t want say death threats, assassination, but that’s what happened.

“That was even more pressure now. Onstage, I was fucking moving like I’ve never moved! I wouldn’t be in the same position for more than two seconds. I lost weight on that tour.

“But look, the way I see it is, what are my other options? Not speaking the truth? And then, am I an artist or am I a musician? No, I had no choice. I’m still so naive to believe that the truth should overcome.”

Did success go to your head at any point?

“It’s a business made for the ego, but this is where my previous life came in. I didn’t start playing music at the age of eight and it was the only thing I ever dreamed of. When someone would come up to me and go, ‘Hey baby, you guys are the best thing since sliced bread’, I was always, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, whatever.’ I didn’t buy into the hype. It helped me keep my sanity within that egotistical world.”

System went on hiatus in 2006, which was largely down to you. Were you thinking, ‘That’s it, I’m done with System.’?

“I didn’t know what the future held, but I did know that I wasn’t completely done with System. If I wanted to leave, I would have left – there was no gun to my head. A successful band becomes a machine – it becomes a cycle. I wanted time to do my own things, I was bothered by some of the internal dynamics, etc. So I went off and made solo records, I started writing for orchestras. When I came back to System, I came back as a more confident songwriter, as someone who had done other things. To me, that’s more useful to add to the value of the group.”

System reunited in 2010. Has all the drama surrounding the band in recent years overshadowed the music?

“Never. Show me a band that doesn’t have drama, and I’ll show you a shitty band. There’ll always be drama – we’re four individuals who feel different about different things. But the press has played it up, and it’s kept the band in the limelight irrespective of our lack of making a record for 14 or 15 years.

“We put out two songs for Artsakh [2020’s surprise-released Protect The Land and Genocidal Humanoidz], which to me is one of the best things we’ve ever done as a band, in terms of reaching beyond ourselves. And I’m extremely proud of my brothers in System Of A Down that we were able to accomplish that. But yeah, you know, the drama’s gonna be there, always.”

It seems pretty intense being Serj Tankian. Do you ever get the urge to just pour a big slug of Jack Daniel’s and crank up Mötley Crüe to shut out the world?

“Ha, no. My method of dealing with things is meditation as much as possible, just slowing things down. For the last couple of months, I’ve been dealing with extreme back pain, a herniated disc – I just had surgery a week ago. This is the result of being overwhelmed by many things – the war in Artsakh, seeing a number of young people die, trying to be helpful, and it feeling like it’s not enough. You know how in music you should never take yourself too seriously? As an activist, I might have taken myself a little too seriously. Pain is a good teacher in that sense.”

What kind of movies do you like to watch?

“I like films that go over the top. I like a good British gangster movie – any Guy Ritchie movie, Gangster No.1, Sexy Beast. To me, those are the funniest movies – they start with a normal script and then shit just goes over the top: ‘This can’t be real!’ I’m a pacifist mostly, but those movies are hilarious.”

Have you had any acting offers?

“I get offered acting roles all the time. Anything from the typical heavy metal, demony type of thing to proper dramatic roles, but it’s just not what I’m interested in. My good friend Ilya Naishuller [who directed the video for Serj’s single Elasticity] said, ‘You need to act, man.’ I’m, like, ‘Fuck no, I don’t want to act. I can’t remember lines unless I’m singing them.’”

You’re a singer, a composer, a poet, a filmmaker, an activist. Acting aside, what can’t you do?

“Never tell a kid he can’t do anything.”

What would have happened, all those years ago, if you hadn’t pulled your car over to the side of the road and had your epiphany?

“I’d be a miserable lawyer, probably.”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.