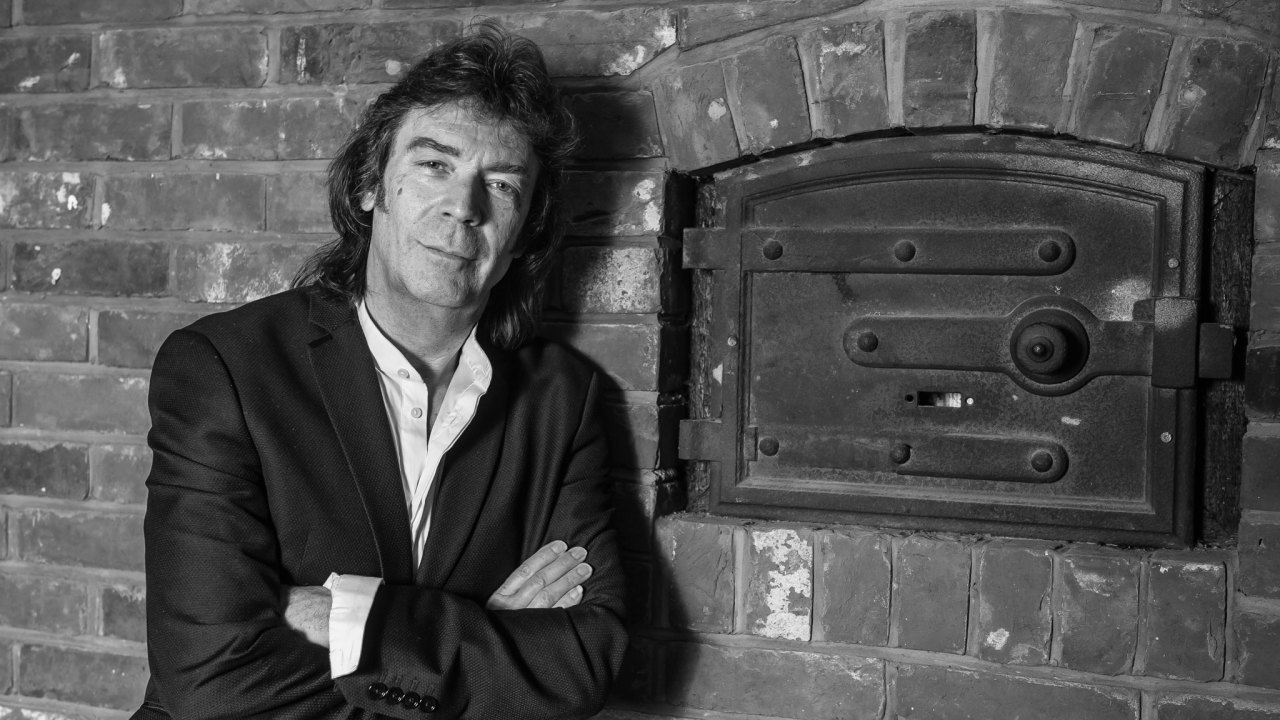

Steve Hackett: The Bits You Didn't Read...

Read the extra material from this issue's Steve Hackett feature that didn't make the print magazine...

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Wolflight is your eighth album in as many years. Allied to your heavy touring schedule, how do you account for all this productivity?

Most musicians have a five-year window to do everything that they want to do and then they pack up. Either the industry deserts them or they desert the industry.* *I’ve never been slack, but I think I’m doing more gigs than ever. Last year was a heavy touring year, this one is more about getting things ready, working on all the things that attend records. So I’m putting more time into videos and organising myself in all sorts of ways.

When did the concept of Wolflight take root?

About two years ago I started thinking about it. Parallel with all the touring I was doing, I was nipping in for odd days and odd weeks. It had to be a series of commando raids.

Is it fair to say it’s the third in the trilogy that started with 2009’s Out Of The Tunnel’s Mouth? There’s a continuing theme of transformation…

I’d certainly go along with that, working in a new way. I think it was the first of the albums where I realised the box was mightier than the building. In other words, your studio can be the size of a computer, which many of us are finding these days. You have to be flexible and the constraints of the industry, at this point in time, require us all to be like that. It’s thinking on your feet. Or on the bed perhaps.

How does the songwriting partnership work between you and your wife, Jo?

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Many of the songs are co-written. What’s good about it is that Jo is always concerned that there’s a variation, she doesn’t like too many repeats of things. She’ll often say to me: “Oh, that line could be more emotional. How about this for a top line?” I think it’s easy to slip into old patterns, but sometimes the old patterns are justified and if at any point there’s a disagreement, I’ll say, “Well, let me follow this through and I’ll convince you why this idea works.” The devil is in the detail. And the saviour is in the detail as well. I think all songs can be saved by patient attention to that. There’s no such thing as a duff song, it’s just a case of ‘Well, it needs a little help from several schools of thought.’ You’ve just got to have the patience to try them all out. You can blunder through with big drums and make an absolute doodle into a monument. But equally, if you’ve got some solid music you can pare it right down to acoustic guitar or piano. It worked for Chopin, didn’t it?

The title track of Wolflight, a folk-classical epic that sounds like a suite, is a perfect example of different genres talking to each other…

Yes, but of course the conduit is very often via rock. I’m interested in melodies, they can work in many different ways and in many different arrangements. I haven’t clocked the man hours on that song, but I remember starting with the main riff that accompanies the chorus. And the chorus was really an afterthought, because here was something that didn’t really require a vocal. But then I saw the Wolflight as a sort of animal call, a voice in the wilderness.

What metaphor were you reaching for with wolves?

The idea of Wolflight was the hour just before the dawn, when something changes from day and night. And I found myself very often up at that time of day, working. Then there’s the whole idea of wolves as totems and the relationship between man and wolf. I did meet a pack of wolves in Italy, about an hour outside of Rome, which is the home of the Romulus and Remus myth of course.

This was for the album sleeve, right?

Yeah, there was one who was basically regarded as the alpha male by all these wolves and I thought: ‘I’m going to have to go in there with them!’ There were about ten of them. What was lovely was that they had wolf cubs and they seemed to immediately want me to play with them. They seemed to know what I was thinking, they seemed to be telepathic.

The album itself is very pan-cultural and historical. Is that tied in to the fact that you and Jo like to travel?

I think it is. It certainly informs the music, Ancient Greece for example. We visited Delphi and the place where divination first took place, in a place called the Corycian Cave, which relates to the song Corycian Fire. It’s an extraordinary place of natural rock formations, where you feel there’s a presence of something monumental. Although Delphi was sacked by the Christians and levelled, the cave is still there, where predictions were made and where, arguably, the mephitic gases informed the predictions. I find that very interesting. Right back when I was making my first album, Voyage Of The Acolyte [1975], there was still the idea of tarot cards and oracle, so it’s been a lifelong fascination for me.

Another new song, The Wheel’s Turning, was inspired by childhood visits to Battersea Fun Fair. Was music already a part of your life then?

Oh yeah, hugely. I grew up playing harmonica first of all. My dad played a number of instruments, so from the age of two onwards I was trying to do music. By the age of three or four – and I know it sounds big-headed - I could actually play tunes on the mouth organ. It was just because I was doing what was natural, trying to copy my dad. I miss my dad greatly. He was my first musical influence, he’d play me cowboy songs: Davy Crockett, Roy Rodgers and all of that. And he introduced me to my first guitar of course. He brought me a guitar back from Canada, though I wasn’t big enough to get my arms around it until I was about 12.

Like many people of your generation, you grew up with The Beatles and the Stones. Then you discovered Bach and Segovia. What effect did that have?

When I first heard Segovia playing Bach, from the very first note I just fell in love with it. It seemed like a whole world of possibilities opening up and there was this incredible sweetness that went with it. He was incredibly accomplished, there were no bum notes for a start. And I realised that what I usually listened to was comparatively quite primitive, even the best of R&B and blues, which seemed to be all about the soloist. It didn’t seem to be as much about the harmonies. Whereas Bach used great harmonic exploration, never mind the rest or the technical difficulty of trying to play that stuff. I thought, ‘My God, this medium is so self-sufficient.’ And over time I realised that not only was there all this complexity, he was also informing it with different tone colours. It was a living miracle that any of that was possible. So while I made a conscious decision that I wasn’t going to devote my life to becoming a classical guitarist, I wanted to take on board some of the influence of that.

Horizons, from Foxtrot, is a good early example of that influence with Genesis…

Yeah, there’s a bit of Bach in there. And even earlier, from the Tudor composers, William Byrd and a piece called The Earl Of Salisbury, that I recorded years later._ _The Genesis idea never really closes, of course. It was more than a chapter in my life and I brought back the book of Genesis in as much as I was capable of doing, with a band that loved the music and didn’t have any agenda other than just doing the best music available. I spent a long time making [2012’s] Genesis Revisited II and touring it all over the world. We did 20 countries last year and I could’ve done more. So I’m back to solo stuff this year, but at the same time I will do some Genesis stuff, but not exclusively. Because I’m not ready to be pensioned off just yet.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.