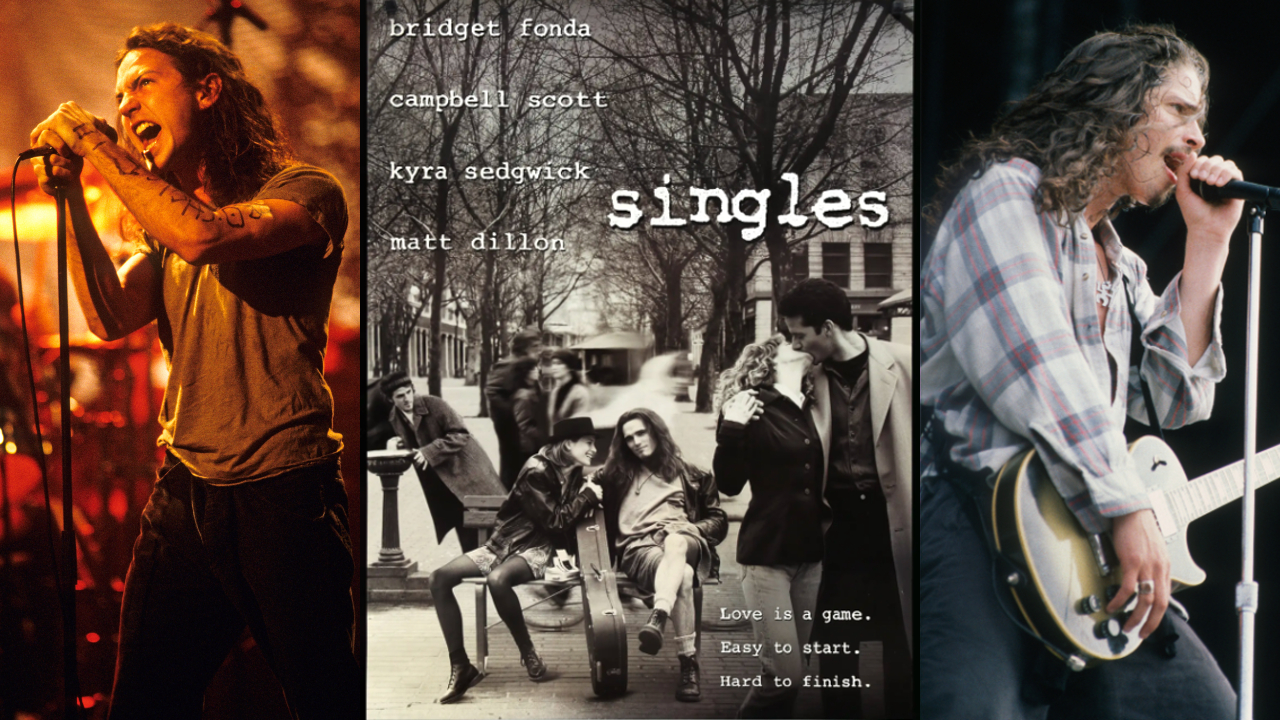

Singles at 30: how a rom-com soundtrack became grunge’s greatest mixtape

How an early 90s film soundtrack featuring Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Alice In Chains and more helped launch the grunge revolution

No one was more dismissive of the great grunge gold rush than Mudhoney’s Mark Arm. “Everybody loves us/Everybody loves our town,” sneered Seattle scene lifer Arm on his band’s 1992 song Overblown, skewering the city’s transformation from remote musical outpost to magnet for Black AmEx-wielding music business bigshots looking to sweet-talk the first bunch of plaid-shirted goatee-farmers they came across into a major label record deal.

The only thing more ironic than the song’s lyric was where it appeared: on the soundtrack to Singles, a sweet-hearted Gen-X romcom starring Matt Dillon, Bridget Fonda, Campbell Scott and Kyra Sedgwick as a pair of on-off couples living in the same Seattle apartment block. Mudhoney may have been rolling their eyes at their hometown’s unexpected popularity, but Singles and its all-star soundtrack were the perfect advertisement for what was happening up there.

Filmed over the early summer of 1991 though not released until September 1992, the movie’s USP was that it used the grunge scene as a backdrop to the characters’ lives and romantic entanglements, most obviously via Dillon’s struggling musician Cliff Poncier, a dim-bulb Eddie Vedder/Chris Cornell manque who fronted a going-nowhere-fast band named Citizen Dick. As the film’s director, Cameron Crowe, told Rolling Stone in 2017: “I wanted to send a visual valentine to Seattle and its one-of-a-kind mix of music, culture and community.”

This was evident on the movie’s stellar soundtrack. Crowe was a music guy to the bone – he’d started writing for Rolling Stone as a teen in the early 70s, and his first film, 1989’s Say Anything, featured music from such hip-for-their-time bands as Living Colour, Fishbone, The Replacements and little-known Seattle outfit Mother Love Bone.

With Singles, Crowe tied things up even more tightly. He made a conscious choice that the songs he used would not only be integral to the fabric of the movie, but would reflect the characters’ own lifestyle. “The whole concept for the soundtrack was definitely a mixtape that you would give to a friend, and not something that you would sell,” he told Rolling Stone.

He was perfectly placed to deliver on that concept. Crowe had moved to Seattle in the late 80s after marrying Heart guitarist and long-time Jet City resident Nancy Wilson. Heart themselves had been embraced by a younger generation of local musicians, among them Soundgarden and Alice In Chains. When it came to persuading bands to appear on the Singles soundtrack, Crowe and co-producer Danny Bramson found the wheels were pre-greased. “I was immediately getting thrust into a community of great music and great people,” recalled Crowe.

The Singles soundtrack album would inadvertently reflect the hierarchy that had already established itself in pre-Nevermind Seattle. Mudhoney may have been grunge’s tribal elders, but Alice In Chains were the big success story – their debut album, Facelift, had recently gone gold in the US, the first album by a band from the local scene to do so. It was their song, Would?, that opened the record: a slab of hypnotic, metal-edged grunge that laid down an early marker for their magisterial second album, the yet-to-be-released Dirt album.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Would? itself was a tribute to Andrew Wood, the charismatic Mother Love Bone frontman who had died from a heroin overdose in 1990 just as the band were making a name for themselves outside of the Pacific Northwest. Wood was the scene’s first significant casualty, and Crowe’s decision to include Mother Love Bone’s soaring Chloe Dancer/Crown Of Thrones on the Singles album felt like an elegy.

Proving that Seattle’s music community was nothing if not tight-knit, Wood had been the flatmate of Chris Cornell, who made two appearances on the Singles soundtrack. Soundgarden’s jagged but melodic Birth Ritual was a bridge between the bruising assault of their early records and the muscular melodicism that would soon help turn them into one of the key rock bands of the 1990s. More startling was the Cornell solo track Seasons, an airy acoustic number that evoked the more bucolic parts of Led Zeppelin III (Crowe later said he originally had the Soundgarden singer in mind for the role of Cliff Poncier).

If Singles rubber-stamped Soundgarden and Alice In Chains’ respective ascents, it acted as a launchpad for other bands.

Crowe enlisted the then-unknown Pearl Jam, recently formed from the ashes of Mother Love Bone, to contribute two songs to the soundtrack: the exhilarating Breath and State Of Love And Trust, the latter an all-time classic that was as good as anything on the band’s debut album, Ten, which was well on its way to selling ten million-plus copies by the time Singles came out. “Eddie had read the script and wrote a new song for the movie, about relationships,” Crowe told Rolling Stone of State Of Love And Trust. “It became the soul of the movie in many ways.

At the other end of the scale, Ellensburg, Washington’s Screaming Trees had already released five albums by the time Crowe enlisted them for the Singles soundtrack. Their contribution, the brilliantly world-weary Nearly Lost You, was one of the standout tracks, raising their profile ahead of their breakthrough sixth album, Sweet Oblivion, released a few months later.

The soundtrack wasn’t just a shop window for the current generation of local bands. One of the standout tracks was Jimi Hendrix’s patchouli-soaked May This Be Love, a track that the Seattle-born guitarist had recorded back in 1967. Elsewhere, the Lovemongers – aka Crowe’s wife Nancy Wilson and her sister, Heart vocalist Ann Wilson – turned in a heady version of Led Zeppelin’s The Battle Of Evermore (the Wilsons owned a studio, Bad Animals, in Seattle, while Zeppelin’s infamous ‘Red Snapper’ incident reputedly took place at the city’s Edgewater Inn).

Ironically, two of the finest songs on the soundtrack album came from out-of-towners. Paul Westerberg, the former leader of chaotic Minneapolis punk rockers the Replacements, served up a 24-carat gem of a tune with the rootsy, just-the-right-side-of-ramshackle Dyslexic Heart (a second Westerberg song, Waiting For Somebody, was almost as good). And Chicago’s The Smashing Pumpkins, a band who were never quite hip enough for Seattle’s cool-kid clique, ended the album on a transcendent note with the coruscating Drown, still one of the finest songs Billy Corgan has ever written.

There was one glaring omission from both film and soundtrack. Nirvana were originally set to contribute a song, only to pull out. No official reason was given, but the startling career upswing that followed Nevermind may have had something to do with it, as did a general desire to distance themselves from the grunge scene. Crowe later claimed that Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love had secretly sneaked into the movie’s premiere via an exit door, though with hindsight, their absence was a blessing. For better or for worse, Kurt Cobain’s snarky, cynical worldview was at odds with the film’s fundamentally good-natured air. Plus Mark Arm had the snarky cynicism well covered anyway.

The Singles soundtrack album was released on June 30, 1992, three months before the movie hit cinemas. “The purpose was to kind of churn the waters for people to know that there was a movie,” Crowe told Rolling Stone in 2017, adding that the success of Pearl Jam and Nirvana had chivvied the studio to release a film that had been sitting on a shelf for almost a year.

Yet the album was more than just an audio trailer for the film. It captured what was happening in Seattle far more effectively than what was on screen, which was essentially a dry run for the couples-falling-in-and-out-of-love-in-a-coffee-house trope that would become so popular later in the decade (sidebar: TV network NBC asked Crowe to direct a TV show based on Singles; when he demurred, they went ahead and made Friends instead).

The movie received middling-to-good reviews, with its more disparaging critics slating it as a cynical cash-in, unaware that its delayed release meant that it was actually ahead of the curve. But the album was pretty much bullet-proof thanks to its A-list line-up and the quality of the songs they delivered – if it wasn’t a definitive Who’s-Who of the Seattle scene, it was closer than anyone else got before or since.

As the decade progressed, other filmmakers ran with the soundtrack-as-mixtape idea. Quentin Tarantino delivered hipster nostalgia via Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown, while Oliver Stone roped in Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor to lend an artfully provocative edge to Natural Born Killers. Those, and others like them, were undeniably great, but none captured the moment quite like Singles.

Crowe himself revisited the Singles soundtrack album on its 25th anniversary in 2017, overseeing a deluxe reissue that included songs and bands that didn’t make the original, such Heart And Lungs by psych-tinged trio Truly and Blood Circus’ percussion-heavy downer Six Feet Under. But the main draws were the previously unreleased demos Chris Cornell had written and recorded for Citizen Dick, the band fronted by Matt Dillon’s character Cliff Poncier. They included the fictional outfit’s ‘signature’ song Touch Me I’m Dick (a rag on Mudhoney’s Touch Me I’m Sick) and the stripped-down Spoon Man, which would later be souped-up and renamed Spoonman by Soundgarden, giving them their first major US hit.

In a bitter twist of irony, the reissue was released on May 19, a day after the death of Cornell. Listening to the original album today, it’s hard not to be aware of his absence, and that of Andrew Wood, Layne Staley and Screaming Trees singer Mark Lanegan, who died in 2021.

But the Singles soundtrack is more than just a headstone for Seattle’s fallen musicians. It’s a snapshot of a time, a place, a scene and a flesh-and-blood community – a notion that feels slightly unreal in the relentless digital churn of today’s overwhelmingly online world. Grunge’s Greatest Hits? Not quite. But a landmark in its own way.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.