"I was terrified that Ed was going to kill himself": Chaos and carnage with Pearl Jam at Lollapalooza 1992

How Pearl Jam’s out-of-control shows on the 1992 Lollapolozza tour sparked crowd frenzies verging on riots

By the summer of 1992, Lollapalooza had evolved from a chaotic farewell tour for Jane’s Addiction into a cultural phenomenon reshaping the American music landscape. At the center of this transformation was Pearl Jam, a band booked as an opener but whose explosive popularity was about to change everything.

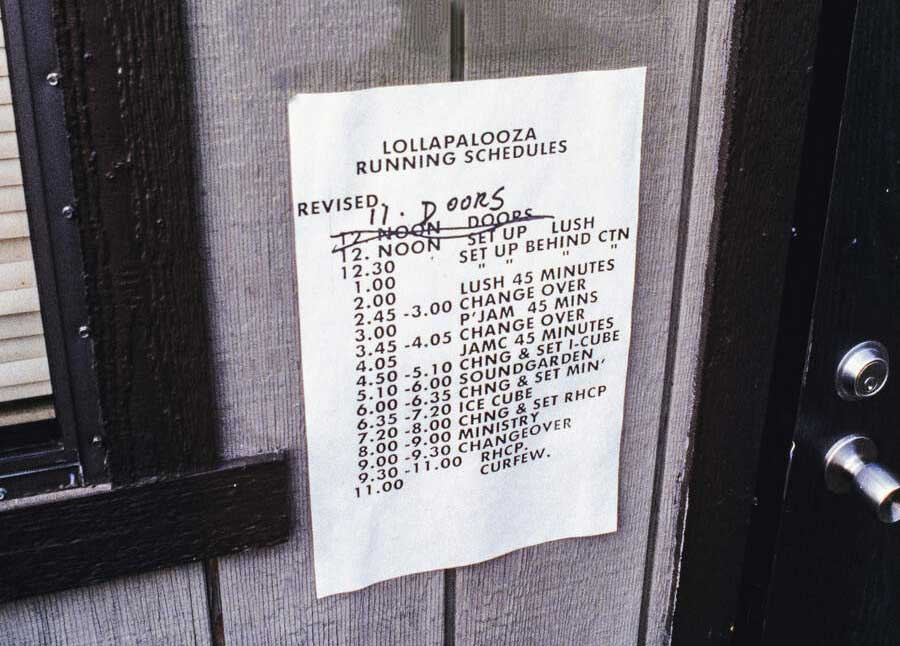

Initially secured by agent and Lollapalooza co-founder Don Muller despite Perry Farrell’s resistance, Pearl Jam was slotted second on the bill. But as their debut album Ten gained momentum and MTV put Jeremy in heavy rotation, the Seattle band found themselves in a surreal position – playing afternoon sets to increasingly frenzied crowds who would “rush the stage at four o’clock sharp” and sometimes literally tear down venue fences to see them.

At the heart of these performances was frontman Eddie Vedder, whose fearless stage presence defined their sets. As one organiser recalls, “Eddie was a monkey. He would climb anything and everything.” Fellow performers and crew members watched with a mix of terror and awe as Vedder scaled scaffolding high above the stage and crowds.

As Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil notes, this was Pearl Jam’s breakthrough “Black Hole Sun moment”, when a band transcends its origins and becomes part of the cultural lexicon.

Kevin Lyman (stage manager, Lollapalooza 1991–92): Lollapalooza, the name, caught on very quickly within the alternative music scene. And I think there were a lot of people who were like, “Oh, I missed out the first year, I gotta go this year.” Combine that with the fact that, by the time we hit the road in ’92, the grunge movement was taking such a grip on the scene. So the shows were crazy. Every day, Pearl Jam would come on and basically the whole venue would blow up.

Miki Berenyi (singer, guitarist, Lush): Lush were the opening band, but we had an extra kind of bump because Pearl Jam had been booked to go on in the second slot. And in the interim between being booked onto the tour and the tour actually happening, they became one of the biggest fucking bands on the planet. So because of that, there was a healthy number of people there when we played. I mean, none of them gave a fucking shit about us, but it’s slightly more rewarding than having the place completely empty. And to Pearl Jam’s credit, I think they were offered to go way up the bill and they were like, “No, no, no, it’s fine. We’re happy where we are.”

Stone Gossard (guitarist, Pearl Jam): Jeff [Ament, bass] and I had been playing music together at that point for ten years. We were in Green River together and then Mother Love Bone, and had gone through a lot in both of those situations. And then Andy Wood, the singer of Mother Love Bone, died [on March 19, 1990, at the age of 24, following a heroin overdose], and we were at that point where we decided to start all over again and to kind of go, “Okay, well, what’s next? How do we do it and how do we find a singer?”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Don Muller (agent; co-founder, Lollapalooza): I was close to signing Mother Love Bone when Andy died. So Stone and Jeff and I had a relationship. And what happened after that was Jeff called me one day, he was in LA, he’s like, “Hey, man, I’ve got this tape. You wanna listen to it?” It was the Mookie Blaylock [Pearl Jam’s original band name] demo. I listened to it and just fell in love right away. As soon as Eddie [Vedder] opened his mouth, I was like, “Yeah, this is gonna be big…”

Stuart Ross (tour director, Lollapalooza): I think we paid them eighty-five hundred dollars a night and they were on second from the start.

Don Muller: We’re all in a conference room at William Morris [talent agency], and Perry [Farrell, frontman, Jane’s Addiction; co-founder, Lollapalooza] comes in and, you know, Perry’s Perry. I don’t know if he was of right mind, I’ll leave it at that, but all he wanted to talk about was, like, these giant communal burritos, where you could sit down at picnic tables and everybody could eat as much as they wanted and then they would leave it for other people. It was, “I wanna do this thing, man…” And it’s like, we were already dealing with health department issues all the way around the first Lollapalooza. But I loved the freedom of how he was thinking.

So then I said: “Perry, we’re gonna put this band on called Pearl Jam.” He’s like, “No way. I don’t fucking like them, blah, blah.” I said, “First off, you don’t even fucking know them.” They were out at the time opening for the Chili Peppers and Smashing Pumpkins on a theatre run, and I said, “We’re doing it.” And I went head-to-head with him. It was nasty. We were across the table from each other. It almost came to blows in a weird way.

Stuart Ross: Obviously we didn’t know – maybe Don did – that they were going to be enormous. And so their position on the bill was, um, complicated.

Kim Thayil (guitarist, Soundgarden): I believe Pearl Jam went through the roof when the Jeremy video came out that summer.

Mike McCready (guitarist, Pearl Jam): There was this sort of feeling of something’s happening and it’s bigger than all of us in the band, so we’ve gotta embrace it. Because now it’s out of our control, you know?

Kim Thayil: That was their Black Hole Sun moment. Which was a moment, by the way, that we had not yet had at that point. Even though we were playing more in the early evening and they were playing in the afternoon.

Stuart Ross: If you think of it logistically, you have eighteen thousand people coming to the show. They didn’t scan tickets back then. We did not have the same entrance efficiency levels that we have now, because they were paper tickets and had to be examined. Somebody had to look at your ticket, tear off the stub, maybe there was a pat down to make sure you wouldn’t bring in stuff you shouldn’t have brought in, and then you came in.

But so many people wanted to see Pearl Jam that it was not people coming in over the course of the day, hoping to be there in time for the nighttime acts. They wanted to come in early. And we had a really hard time in some cities trying to get people in that early. If we didn’t get people in efficiently, and the kids heard Pearl Jam starting to play while they were still in line, there were times they tore our fences down.

Ellyn Solis (publicist, Epic Records): It was this feeling of, like, riding a tiger at that time. And we couldn’t keep up with it.

Stone Gossard: Having gone through everything we’d gone through, and then to get to the point where we had made a record and now people are actually starting to come to see us – and this is after watching a lot of Seattle bands have some real success and not knowing if we even fit into that world – it was a thrill. It was also nerveracking. On a lot of levels, I was out there just fucking shaking, in terms of wanting to be confident enough to live up to that excitement and also not always knowing whether it was justified by what we were doing.

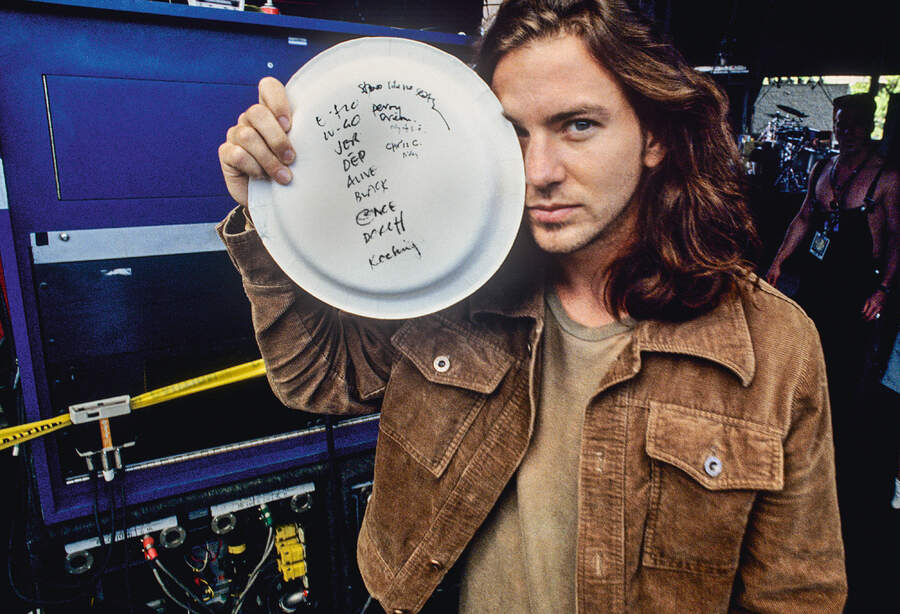

Mike McCready: It was very bizarre and exciting, like, “What the fuck is going on?” And we didn’t have a ton of music back then, just the first record and one cover – The Beatles’ I’ve Got A Feeling, I think. But it was mind-blowing because you’d see these kids just rush the stage at, like, four o’clock sharp, in a frenzy and jumping over seats. They were just so passionate about seeing us.

Kevin Lyman: It was right on that teetering brink of complete chaos. The crowd, without any instigation or anything, had to be close to that stage. So they would almost invariably overrun security and it was just a sea of people coming forward.

Lynn Hazan (front-of-house tour accountant, Lollapalooza): All the crew guys would go and try to prevent the riots and the mosh pits from really coming in. I would be on the side of the stage when Pearl Jam performed, and one of my jobs was that everybody would take off their rings and give them to me. So I would stand there with everybody’s rings on my fingers, because nobody wanted to hurt any of the fans.

Michael ‘Curly’ Jobson (stage manager, Lollapalooza 1991-92): We had twenty thousand kids all crushing into one another and we were pulling them out like lemmings, boom! Just outta control.

Jim Rose (founder, performer, MC, Jim Rose Circus Sideshow): You can watch the Jim Rose Circus all you want, but the greatest circus performer on that tour was Eddie.

Nikki Gardner (special groups co-ordinator, Lollapalooza): Eddie was a monkey. He would climb anything and everything. That in itself was a bit challenging just because we obviously didn’t want anything to happen to him.

Perry Farrell: I remember Eddie did a second-storey dive off the speaker stacks into the crowd. I thought, for sure this guy broke something.

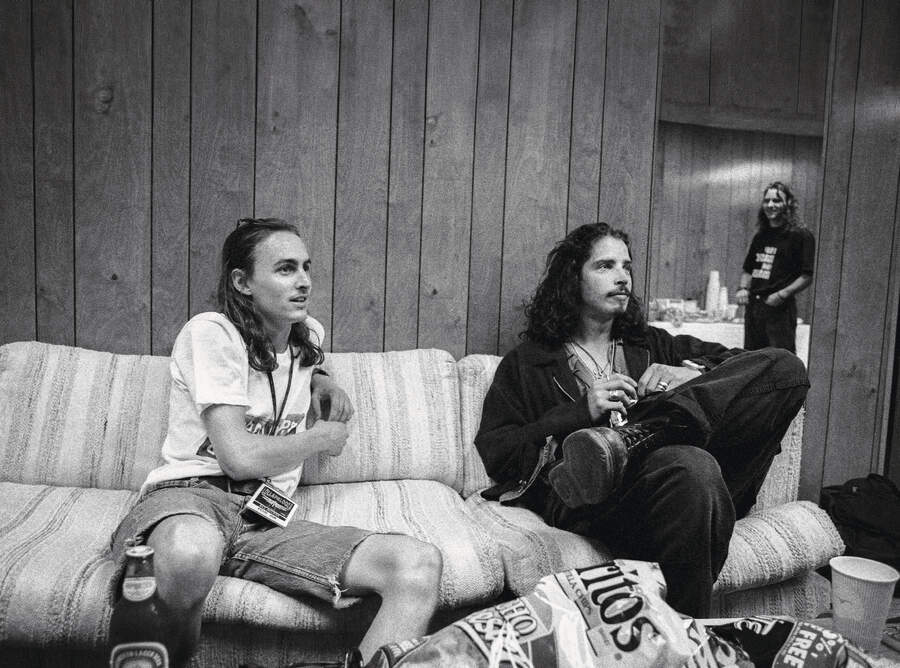

Kim Thayil: Chris [Cornell] and Eddie, they bonded on that tour over riding bikes and climbing pipes, I guess. Back in our club days, Chris would regularly climb the ductwork and piping work of the venues and treat it all as his personal monkey bars and swing out over the crowd. And then Eddie started doing that on Lollapalooza.

Stone Gossard: It kind of became part of the show in the sense where, if he felt he needed to or was willing to take it over the top by doing something extreme like that, he would take that chance, and just let the music sort of carry him into some other place.

Phil Burke (head rigger, Lollapalooza): There were a couple times when he actually got up on top of the roof. And you’re not dropping down from there – that’s, like, fifty feet in the air. But most of the time it was just kind of climbing up the side scaffolding, by the PA. And those outdoor stages, they’re scaffold-based. So it’s kind of like a big jungle gym anyway.

Mike McCready: We’d play Porch and he would just take off and start cruising up. And it was like, “Oh, here he goes again.” It was exciting and I was also terrified that Ed was going to kill himself. Then he’d jump into the crowd and come back on stage and he’d have all these fingernail markings on him.

Eddie Vedder (singer, Pearl Jam): We’d get to the hotel after the shows and I’d feel pretty good physically. And then I’d take a shower and realise that I had, like, a thousand deep scratches on my back.

Andy Langer (journalist and radio host): Each time he climbed I remember watching Jeff and Stone and the guys, and they would sort of watch their fingers – because they weren’t a jam band but they were forced to improv, improv, improv and stretch out the song – but they were also just as curious and just as wrapped up in the situation unfolding above their heads as we were. Because there was a better-than-likely chance that we all were about to watch a guy fall and die. And no question, death would’ve been the result.

Phil Burke: I was tasked with getting his wireless microphone back when he went on his climbing adventures. So we would go up together. He would start climbing, I would follow him, and then he would give me his really expensive wireless mic and I would get it back down and give it to the monitor engineer. But it wasn’t discussed or rehearsed. It was all spontaneous.

Eddie Vedder: Over the gigs it got higher and higher. You’d do one, and then you’d notch it up because you survived the last one, so… We’re gonna take this to some level that people aren’t gonna forget. And if that means risking your life, we’re gonna do it.

Phil Burke: Would I have preferred he not do it? Yeah. But that was not my thing. My thing was, “Get the microphone before he drops it.” Because even today those mics are really expensive. And you know, it’s a lot easier to climb up with it than climb down. You kinda need both hands on the way back.

Stone Gossard: I think when he stopped doing it, we were all relieved. Because as fun and exciting as it was, it was gonna end badly at some point.

Al Jourgensen: (singer, Ministry): Eddie was a gas on that tour. At one point we had three days off, so he flew with me from Atlanta to Chicago, just to stay at my loft for a few days and party. He was game for anything back then. Of course, now he’s very serious and an erudite citizen. But back in the day? Yeah…

Mike McCready: I remember being at a hotel somewhere down South, and Chris Cornell and Ed throwing a TV out a window. They were doing it to mock actually doing it or something. I don’t know. But I think they freaked out a little bit, because it was still kind of dangerous.

Jim Rose: I was walking past the hotel and a fuckin’ television comes hurtling down and splats right next to me. They didn’t know I was walking by.

Kevin Lyman: The craziest thing was when we did Jones Beach in New York. Right when Pearl Jam was coming on, a giant storm swept up through the bay there. And I’m on stage and I see our village getting blown up. Tents flying up in the air, we’re trying to evacuate the crowd under the bleachers…

Phil Burke: You’re on Long Island, and when you’re out there you can actually see the weather coming. But it’s not like you get a lot of warning. And this was ’92, so Doppler radar didn’t really exist then. You couldn’t take out your smartphone and look online and see where those weather cells are. So it was really seat-of-the-pants. And, boy, I remember the staging guy coming and grabbing me and saying, “Look at this.” And we looked out over the water and it was black.

Miki Berenyi: What I remember is that everyone all day was going on about it, the weather report, and blah, blah, blah. I’m not really used to American weather. So I was like, “Yeah, whatever.” I thought, all right, it might rain a bit… And basically the very last song we played, I remember saying, “Okay, this might be the last song before the rain comes”. Within half an hour it was just complete insanity.

Mike McCready: A fucking hurricane came in. I remember all my Marshalls went [makes exploding noise].

Lynn Hazan: Somebody said, “It’s a tornado.” And I was like, “It’s not a tornado. We don’t have tornadoes on Long Island.” But I think it kind of was a tornado.

Phil Burke: We got Pearl Jam off the stage, and then we immediately lowered everything. I think we had maybe ten minutes before that first cell hit, and the first one was really, really violent. It was picking up the roof probably five or six feet. This thing’s still hanging on twelve three-ton motors, and it was getting lifted up, unweighting everything, and then dropping again. So you’ve got sixty thousand pounds getting lifted five feet and then free-falling five feet. I’d never seen anything like it.

Miki Berenyi: I think two people got blown into the fucking sea.

Phil Burke: I know Curly went for a swim.

Michael ‘Curly’ Jobson: I was on top of the stageright PA stack, strapping down tarpaulins to weatherproof it. Was I silly for being up there? Probably. Anyway, it hit us, and I got blown clean off the top. Just picked me up and threw me in the air. I didn’t have a hope. Then I was in the water, underneath one of the walkways, trying to crabcrawl my way out of the situation. And at that stage in my life I couldn’t swim.

Andy Langer: The bathrooms were big concrete structures, and I ducked into a bathroom-slashlocker room. And the Pearl Jam guys were in there. The Soundgarden guys were in there. At one point Vedder and Cornell started leading everyone – their bandmates and roadies and people like me who dove into whatever cover they could find – in a mini-Sinatra set. I think it was just sort of nervous coping. We were safe, but we were also scared.

Kevin Lyman: We cancelled the show. Our lighting rig was kind of destroyed, and we had to send it down to Georgetown University so they could fix it and put it back together. But my friends in the Ramones’ crew came to visit us that day, and the Ramones always had their own lighting system. And we’re like, “Oh my gosh, we have to go to Waterloo Village,” in Jersey, which was our next show.

So I hired the Ramones’ crew with their lighting rig to come to Waterloo Village and do our show. It was just a front/back truss, but it worked out fine. All these bands played without their normal lights, their special effects, still conveying all the emotion that was in their music. We just did a straight-up punk-rock show. And there was another date, I think it was Chicago or St. Louis, that Eddie actually got left at a truck stop.

Mike McCready: It was a gas station at, like, four in the morning. He got out and then the bus took off. This was before cell phones or anything. But we show up to Lollapalooza the next day and… Ed’s not there. At a couple of the other shows, he and Chris would go to the second stage and do a Temple Of The Dog song, so we talked to Cornell and Matt [Cameron] to see if we could do some Temple stuff with them, because we didn’t have a singer. I think we did Hunger Strike and one other song. And we’re starting Hunger Strike…

Kevin Lyman: …and all of a sudden you see this truck pull up, and Eddie’s coming! He had hitched a ride in a semi to the show. Mike McCready: I look up as we’re playing, and I see a guy running through the crowd. I’m like, “What the hell?” And it’s Ed! He’s fucking running from the back of the stadium to get to the stage. There’s some security running with him, and the crowd’s kind of parting a little bit as they come through. And we played right when he got on stage. I’m pretty sure I’m remembering this correctly. We had ten, twenty minutes left, and I think we did four songs and we were off.

Miki Berenyi: At that point, after Eddie’s fucking leapt from the scaffolding and everyone’s gone completely crazy, and then they all fuck off to the merch stall and to get some beers. And then the Jesus And Mary Chain are playing in front of a vanishing number of people.

Kevin Lyman: Basically my whole life revolved around maintaining the venue to get through Pearl Jam, knowing that Jesus And Mary Chain were the most boring band in the world and we could then get the venue back under control.

Excerpted from Lollapalooza: The Uncensored Story Of Alternative Rock’s Wildest Festival, by Richard Bienstock & Tom Beaujour. © 2025 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.