"Purple Rain is like Stairway To Heaven. It's non-religious, but people feel reverent about it": The story of Prince's Purple Rain, this year's viral Stranger Things needle drop

Prince's Purple Rain was the epic ballad that reclaimed rock for black musicians and is now ingrained in popular culture

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

"Prince was very excited," The Revolution’s drummer Bobby Z remembers of the night they introduced Purple Rain to the world. “He was saying, ‘We’re going to make history.’ That’s what he was pushing us to do.”

Prince and his newly christened band were in the dressing-room of First Avenue, the black-painted lobby of a former Minneapolis bus depot which Bobby recalls as a “revered” stage for the city’s musicians. While Prince regularly tried out new songs there, on any given night in its smaller annex, The Replacements, Hüsker Dü or Soul Asylum might be playing too.

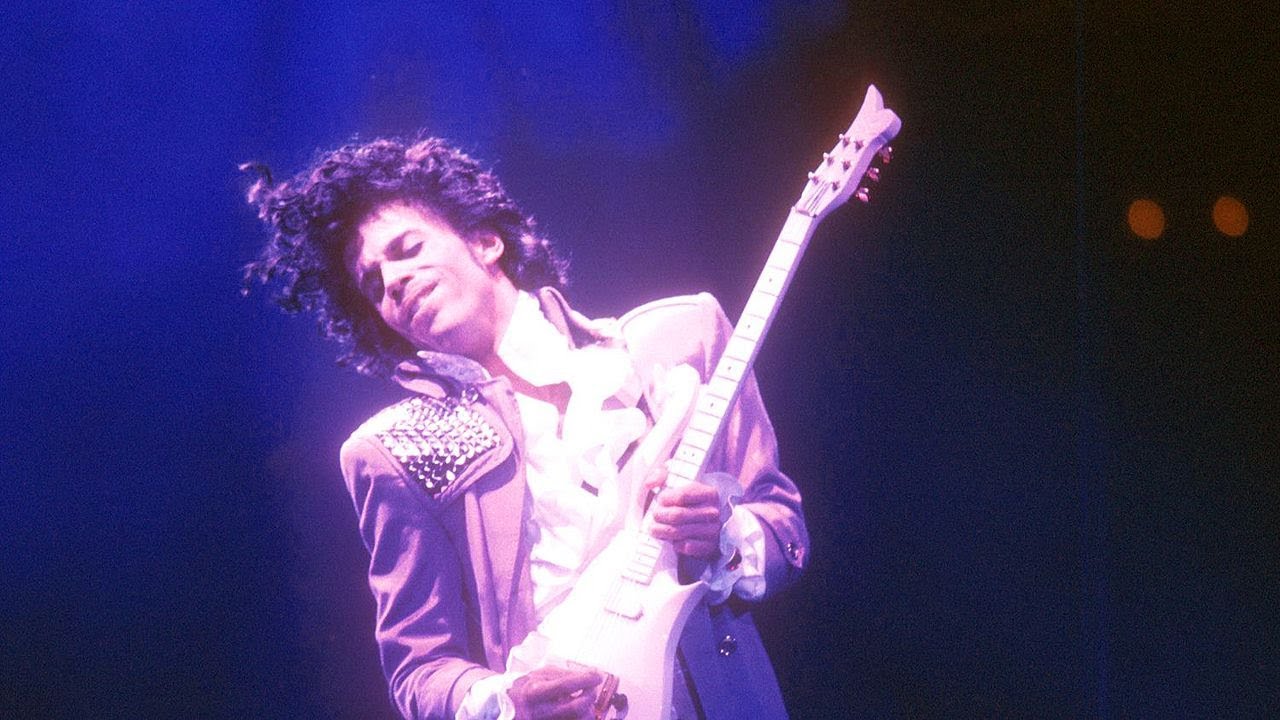

On August 3, 1983, Prince and the Revolution broke off from filming Purple Rain and recording its soundtrack album to play a 45-minute benefit gig for their choreographer, Loyce Holton. They ended with Purple Rain, a slow-burning, 10-minute ballad which began on acoustic guitar and erupted into an electric frenzy. With minimal overdubs, the performance closed the album and film which sent Prince onto 80s pop’s Olympus. Purple Rain also completed the musician’s mission to reclaim rock for black musicians, and fuse it with anything else he felt like.

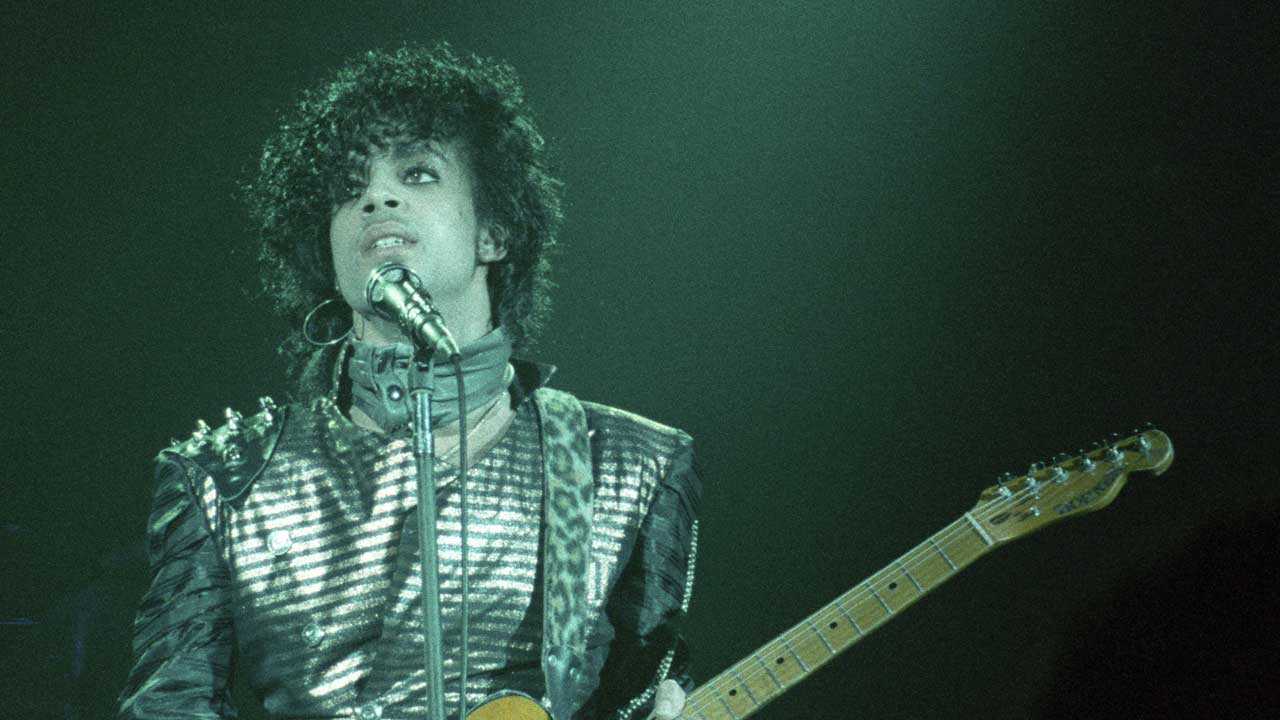

“One of the great successes we experienced was not to just be thought of as a black R&B band,” Revolution keyboardist Lisa Coleman believes. “We had struggled for a couple of years, trying to write one song for a black music station, and one for a rock station. But Purple Rain the song was played on every kind of radio station, from country to Americana to rock ballad. And it’s just so perfect that it came from Prince, who nobody knew what to make of. Are you serious? Who is this guy?”

The question went to Prince’s heart, Coleman believes: “He never wanted to lose his black audience, that was really important to his identity. Because even within the black community, there was tension about how light his skin was, whether or not he was gay. Can we really call him one of us? That mentality was important to him, but he also was trying to grow beyond that. I think it was a struggle for him, all of his life.”

Having been reduced to tears by bigoted Stones fans when he supported them in androgynous garb in 1981, the Purple Rain album sleeve saw him astride a motorbike sporting a Little Richard pompadour, while on the record he was a Jimi Hendrix-like virtuoso, in defiant riposte to music which had buried its black roots.

The Revolution first heard Purple Rain at the Minnesota warehouse where they recorded most of the album. “It was on Highway 7, out in the boondocks,” says Coleman. “He was messing around on guitar, calling out the chords. And then Wendy [Melvoin, the band’s teenage rhythm guitarist and backing singer] started playing the chords in her Wendy way, and he loved it! The intro is Wendy, and her voicings on those chords are beautiful and Joni Mitchell-esque. I came up with the string parts. During the course of that day – maybe a day or two? – it just came out of us.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

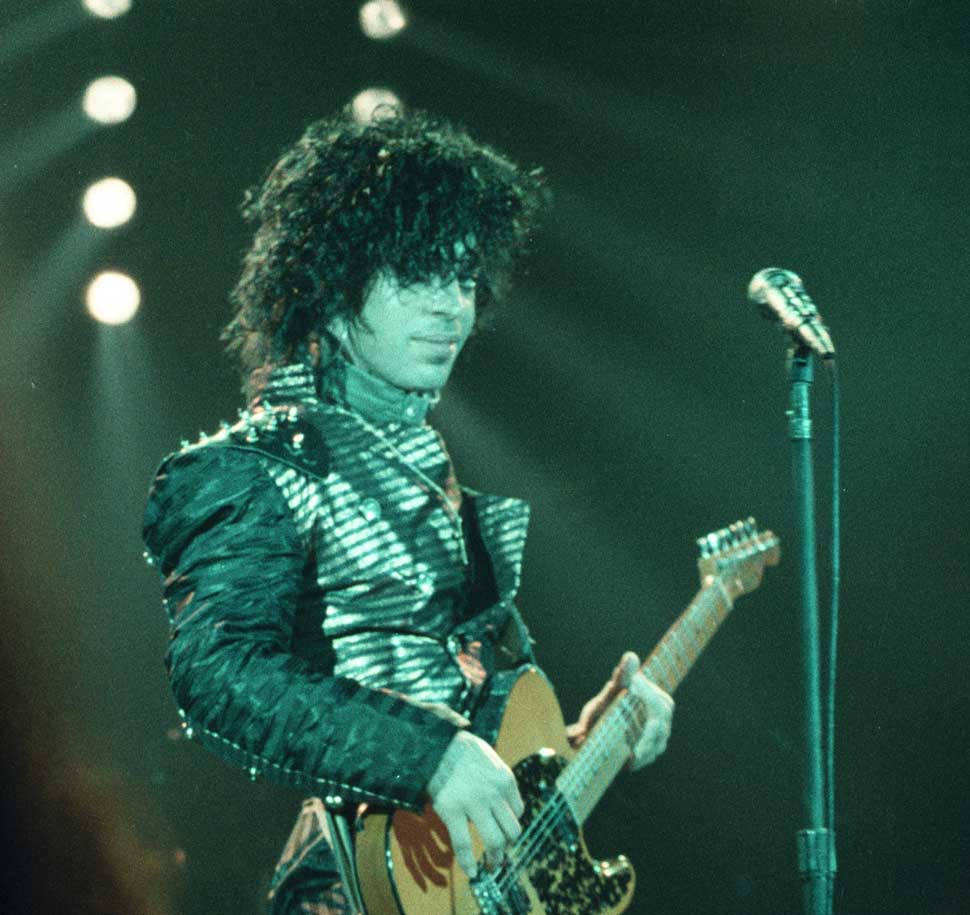

A Record Plant mobile recording truck was outside First Avenue when they turned up that August. Inside, it was hot as hell. “It was pushing 90 degrees Fahrenheit and dense with cigarette smoke,” Bobby Z explains. “It was a toxic environment.”

Coleman remembers the club being “packed with people”. The band were exhausted from the album and film, adding to the heightened atmosphere. They’d also be playing music the crowd hadn’t heard.

After Melvoin’s opening acoustic chords, Bobby Z’s drums – mostly acoustic, and triggering Linn drums later added to in the mix – accompanied Prince’s singing for the first two minutes.

“It’s just a back-beat and him from his guts,” Bobby says. “It’s just so raw for him. I remember those two minutes. Because the room is silent except for the pattern you’re playing. He was in the moment, and you’re in it with him, and it was a special place to be. It was a whole different planet.”

“That night it was on fire,” says Coleman, “and nobody’s singing along. It was just so different for Prince, almost a country song. But it got to them by the end, and his guitar solo was so beautiful. I get chills thinking of it. I always kept my eyes on Prince, in case he needed something, but I could see the faces and wide eyes in the front. It was like a kid seeing Santa Claus.”

Coleman knew how they felt. “I remember Prince’s guitar solo affected me. And then when the ‘woo-hoo-hoo-hoo’ part came in, and we got the crowd to sing it, that was mind-blowing. Plus I was having this emotional reaction to the beauty of the music,” she laughs. “Just keep playing your part! Pay attention…”

There’s as much tension as release in this atypical rock epic (nearly nine minutes long on the album, after Prince cut a verse, and frequently stretched out to more than 15 when performed live – see Syracuse clip, above). Coleman’s string arrangement – played on her Obie FX keyboard on the night, with a string quartet added in the studio – has a classical, calming quality, as Prince’s voice and guitar clamber for the heights.

“It is that contrary motion that made it cool,” Coleman considers. “The verses are so intimate and personal, like he’s trying to talk to you. He liked the strings coming in slowly, and their warmth. And then, at the end vamp, where they’re going down and he’s going up, maybe it’s keeping it from flying away completely. It’s repetitive, and it keeps saying, ‘I’m here with you.’ And then his guitar solo is pleading, ‘Please be here.’”

“You’ve got this dirge or ballad beat behind it,” Bobby Z reflects. “You’ve got pleading in the vocals. You’ve got agility and spins and pirouettes in the guitar solo. And then the strings pull your heartstrings. Purple Rain is like a Stairway To Heaven. It’s non-religious, but people feel reverent about it. Even if you walk in on a casino and some crappy band are playing it, it still has something different.”

That reverence lasted. Purple Rain became Prince's traditional showstopper, the only song he played live over a thousand times. It was the highlight of what many consider to be the greatest Super Bowl halftime show ever, when Prince braved a deluge to turn in a performance for the ages. It reentered the US and UK Top 10s in the wake of his death in 2016.

And in late 2025, the song was used to soundtrack a climactic sequence in the series finale of the Netflix series Stranger Things. Over the course of the following week, it became the most searched-for song on TikTok, with posts using Purple Rain rising by 3500%. Meanwhile, on Spotify, streams rose by 243% globally overnight, predominantly among listeners who weren't born when Prince hit the stage at First Avenue.

"We knew we needed an epic needle drop, and so many ideas were thrown around," Stranger Things co-creator Ross Duffer told Tudum. "I think there’s nothing really more epic than Prince."

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 260, published in March 2019.

Nick Hasted writes about film, music, books and comics for Classic Rock, The Independent, Uncut, Jazzwise and The Arts Desk. He has published three books: The Dark Story of Eminem (2002), You Really Got Me: The Story of The Kinks (2011), and Jack White: How He Built An Empire From The Blues (2016).

- Fraser LewryOnline Editor, Classic Rock

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.