“I wouldn’t say I was angry, but I was definitely prone to ‘anger moments’… I would explode. The gear-trashing was the real thing”: How Muse took on the world and won

From the moment they started taking themselves seriously, the trio were convinced success would come their way – even as they became more out-there and ludicrous

Muse started out as a series of irreverent party acts before making their first steps towards success in 1994. Even in those early days the trio were convinced they could achieve their ambitions, and in 2013 – after nearly two decades of effort – they told Prog how they’d done it.

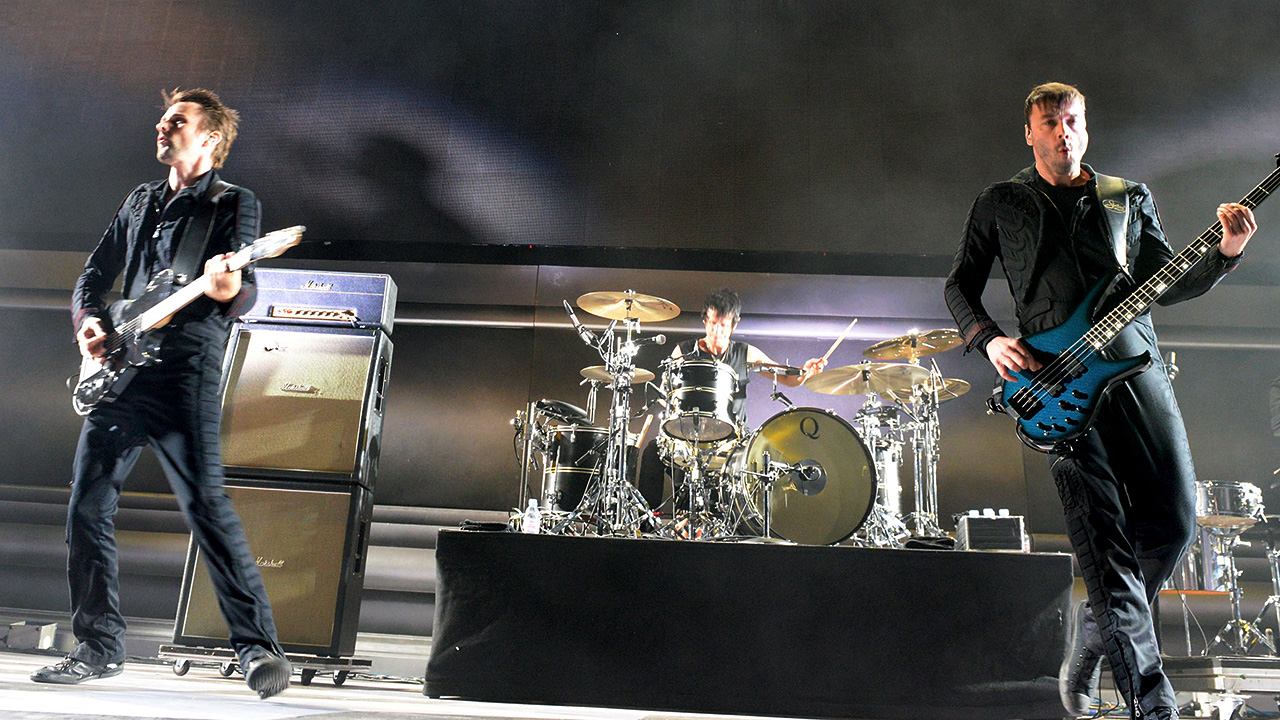

“I can’t believe I actually just did that,” laughs Matt Bellamy, shaking his head in mild bemusement. He’s talking to himself, really. Except that a sold-out O2 Arena rammed with manic Muse obsessives is hanging on his every utterance. What he actually just did was sing a song without the security blanket of his guitar, which he rarely does, and gave it the proper rock-messiah works: falling to his knees, rolling on the stage, shrieking in falsetto. And when he does have his guitar, he gives it even more, to the accompanying roars of the ever-growing faithful. In fairness, he’s got an eye-catching set for support. Featuring a circular runway on which to posture, it’s festooned with banks of video screens which bombard us with images both socio-political and comical. As the show goes on, these screens gradually form a vast upside-down pyramid shape which envelops and consumes the band, before they emerge heroically from within, apparently an unstoppable force.

Backstage, minutes before the band go on, bassist Chris Wolstenholme tells me, “It’s not just a stage. It’s pretty amazing.”

Do you get stage fright?

“If you don’t get nervous in front of 18,000 people, it means you don’t care. You should be nervous. You’re alive.”

Muse are most certainly alive and living the dream now, one of Britain’s biggest bands, with recent sixth album The 2nd Law ruling the roost. You could argue that they’re the hottest rock band in the world, or at least competing strongly for that title. How did that happen? How did three average guys from Teignmouth in Devon go from being just another bunch of teenage garage-grunge hopefuls to all this: penning bonkers Olympics anthems, filling stadia and arenas around the world, selling 15 million albums, fathering children with Hollywood stars, being hailed as the new Queen and being showered with awards across the board. What madness is this? “They let their madness show through,” Brian May has said. “And that’s always a good thing.”

Rather gloriously, they have achieved this stratospheric ascent not by tailoring their act to fit in, but by becoming progressively more and more out-there and ludicrous, with albums that discuss Orwellian dystopias, revolution, aliens, thermodynamics and black holes; music that mixes up wallpaper-peeling riffs, electro-funk and neo-classical symphonies, and a sensory-overload live show that thinks nothing of chucking in a few satellites, giant globes and deeply symbolic explosions.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

They also display a sense of humour, as if to let us know they’re keenly aware that it may be riotously over the top, but as Freddie Mercury would have agreed, that’s the point. They want to see how much they can get away with. In an age where too many interchangeable, forgettable bands mumble and stare at their feet, afraid of being accused of bombast or pretension, Muse reach brazenly for the higher ground, to make a splash, to pin you to the wall. In many ways they are the modern face of classic rock, carrying the torch for the proud heritage that’s burned through Hendrix, Zeppelin, Yes and Pink Floyd. Even though their own early influences were Nirvana, Sonic Youth and Rage Against The Machine, they’re happy to accept the mantle.

“For sure,” agrees Matt Bellamy. “We’ve always liked Zeppelin, Queen, The Beatles. Jimi Hendrix was my first favourite guitarist. When we were growing up we veered towards the bands that were great live performers: Nirvana, Rage Against The Machine had great energy, emotion and drama. Then mid-90s it all got a bit quiet, a bit mellow. When we got up on stage, we always wanted to just give it everything.”

Few bands ‘give it’ quite as much as Muse, onstage or on record. Their transformation from the Radiohead-indebted nerdlings of the late 90s to the hi-def superstars of 2013 reached its apogee with their pyramid-based stage show. Far from exercising typical British restraint and false modesty, it’s shamelessly over the top and loaded with mildly paranoiac meaning. In that respect, you can trace its lineage back to the big daddy of arena rock stage shows, The Wall.

“The upside-down pyramid represents the power structure at its most extreme, the all-seeing eye, and the idea that a powerful elite profits from everyone’s hard work underneath them,” says Bellamy. “That seems to be the way of the world. So the pyramid comes down and gradually consumes the band. You can see something in common with The Wall there, creating a separation between the band and the audience… which ultimately with us is broken down.”

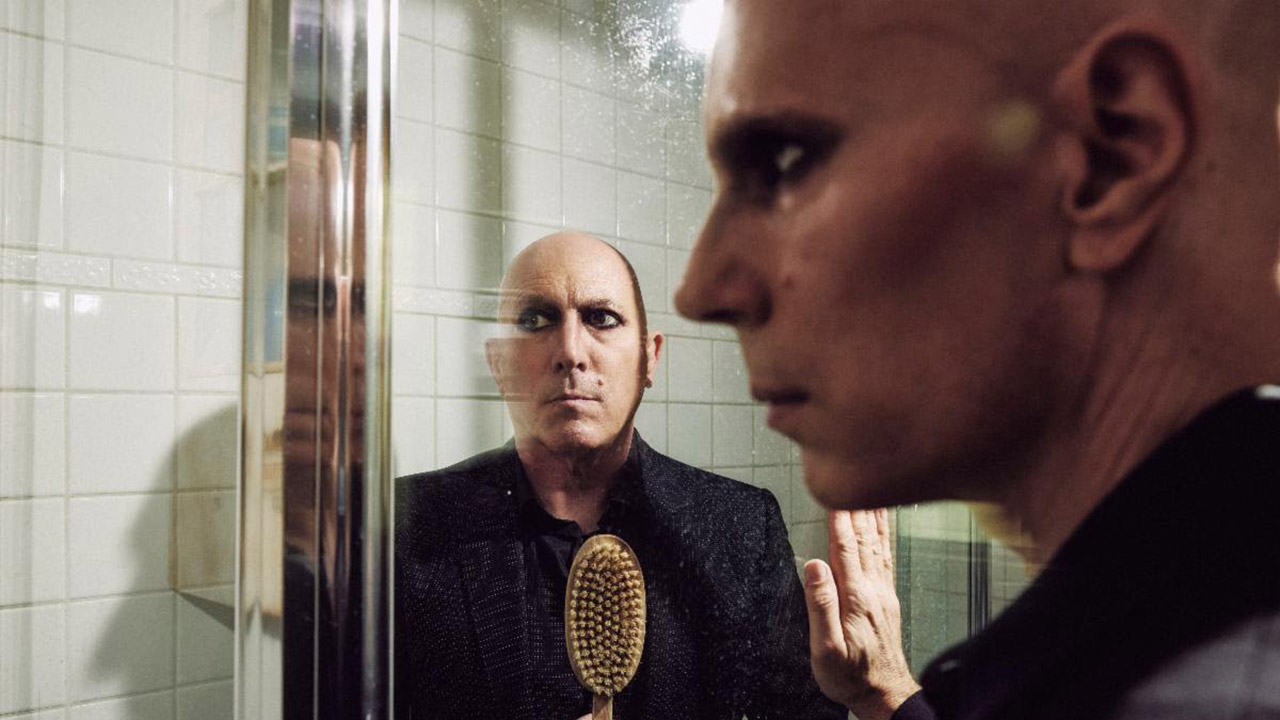

We’re speaking a fortnight after the London show, in a North London café. Black-haired and birdlike, Bellamy sips iced water with a slice of lemon in it. His dad, George, was a member of The Tornados, whose Joe Meek-produced 1962 song Telstar became a transatlantic hit (and pre-dated Bellamy Jr’s own space fixation by 40 years), but at first glance, he couldn’t look less like a 21st-century rock star with a conspiracy theory fixation.

But then Muse have always had one eye on confounding expectations. Even in their younger days, playing the toilet circuit, they came flying out of the gates. Gear was regularly smashed onstage. “In our early years I was genuinely a bit more… I wouldn’t say angry, but I was definitely prone to ‘anger moments’,” he says. “I would explode. On those early tours it was a cathartic experience for us: the gear-trashing was the real thing. But then around the third album there was a period where it was just a bit of fun.”

Is it true you hold the record for the most number of guitars smashed onstage during one tour? Apparently it was 140… “I think that the Guinness compilers or whoever claimed that record for me, they got mixed up. Around 2001 we did 57 festivals in one year, which was a record. They must have assumed I trashed my guitar at every one of them, and at every other gig as well. So I don’t know. It’s certainly not verified. I bet Pete Townshend would definitely have the edge over me on the numbers.”

Conversely, Muse’s early years were as conventional as it gets. Bellamy, bassist Wolstenholme and drummer Dom Howard met in the early 90s in the seaside town of Teignmouth. A series of school bands followed – Gothic Plague, Fixed Penalty, Rocket Baby Dolls. It was as the latter that they won a local battle of the bands competition, destroying their gear in the process. They realised that if others were taking them seriously, they might be wise to do the same, and chose a less silly name, Muse. They forsook university and played learning-curve gigs galore while taking jobs in an ice-cream van (Wolstenholme), on a building site (Howard) and as a caravan-park toilet cleaner (Bellamy).

Far from being an overnight sensation, they nevertheless began to get some traction playing in London and Manchester, supporting Skunk Anansie, and with second release, 1999’s Muscle Museum EP (a self-titled debut EP had appeared the previous year). With a blend of good judgment and dumb luck they signed to a then-new label, Taste Media, in the UK, and Maverick (the label owned by Madonna) in the States, where their potential to “go big” was instantly perceived. John Leckie – who learned his craft working with Pink Floyd in the 70s – came on board to produce their first album, 1999’s Showbiz, and co-produce their second, 2001’s Origin Of Symmetry. “We hadn’t really listened to Floyd until he played The Dark Side Of The Moon to us,” confesses Bellamy.

The leap between their first two albums was astounding: while Showbiz showed hints of the epic sound that would come later, Origin Of Symmetry blazed away from the lift-off pad and didn’t look down, with Bellamy’s burgeoning guitar heroics sending their sound spinning off into outer space. Their third album, 2003’s Absolution, gave them their first No.1, and from there on, they just mushroomed: 2006’s sizzling Black Holes And Revelations with its bizarre slabs of funk and prog; 2009’s The Resistance with its glam-stomp calls-to-arms and dizzying conspiracy theory-themed concept; headlining appearances at Glastonbury, Reading and Wembley Stadium (they were the first band to sell out the new stadium, a few weeks after it re-opened); and, earlier this year, writing one of the official Olympic anthems in the shape of the admirably OTT Survival. The less cool they were with critics – for not chickening out of layering Brian May guitar flourishes over three-part symphonies while recommending we stick it to the man – the more fans adored them, for the very same reasons. The more they sent their music out on a limb and concocted crazier live shows, the bigger they ballooned.

Success has brought with it the expected rock-star trappings: mantelpieces groaning under awards trophies (from Brits to Grammys to a prestigious Ivor Novello), Hollywood wives (Bellamy is married to actress Kate Hudson; they have a one-year-old child) and, in the case of the ursine Wolstenholme, a battle with alcoholism (he subsequently conquered his addiction, writing and singing two songs on the new album, Save Me and Liquid State, about his problems). Not bad going for three blokes from Teignmouth. Do they ever have to pinch themselves and ask, ‘How the hell did this happen?’

“Yes,” says Dom Howard, backstage at the O2. With his slight frame and fine features, the drummer looks like he could be related to Bellamy. “But then this was kind of the plan. In some ways, we never thought we’d get to this level. But at the same time, we always wanted to be the biggest band in the world. If you’d asked me at 15, I’d have gone, ‘What are you talking about?’ But at 18, I’d have gone: ‘Yeah, of course we’ll get there!’ We believed. We always had the desire, and we’ve always taken risks.”

“The first time we played Wembley Stadium,” says Wolstenholme, “I spent most of the set having flashbacks. I was remembering playing to 30 people in Exeter or Plymouth. Of course this is way beyond what we expected then, but we always had confidence. Maybe it was insecurity, but we thought: we’ve got to fill these big spaces up. This is not a band that’s ever been ashamed to say we want to be a big band. During the 90s, it was cool to say you didn’t want to be big. But then why are you in a band? Why do you go and play in front of people? I never understood that. I wanted as many people to like this band as possible.”

In the North London café a fortnight later, Bellamy mulls over the same issue. “It is unusual, absolutely,” he agrees when I emphasise how weird their irresistible rise has been. “But it’s also unusual to hear it put that way. Because I suppose from our point of view, it’s usual to get what we want. I know that sounds odd. But we wanted to be a great live band, and we got it, so… still, luck must be a part of it. Though nobody can deny we’ve been hard-working.”

Muse aren’t just bringing spectacle back to rock. Their albums have been increasingly hinged around overarching concepts that question authority, corporate greed and humanity’s future. It’s all drawn on an epic scale, of course – The Resistance was a grandiose sci-fi rock opera based on what Bellamy described as “a story of humanity coming to an end and everyone pinning their hopes on a group of astronauts who go out to spread humanity to another planet”, all set against a backdrop of global socio-political conspiracy theories.

In that respect, Muse are a protest band – a very modern one, granted, but one who aren’t afraid to call for revolution and for the established order to be upended. It’s a noble idea, but one that could be viewed as naïve, even quaint, in an era when rock music struggles to make itself heard against the din of X Factor and video-game culture. Is it even possible for a rock band to spark a revolution in this day and age?

“Oh, I think nowadays probably more so,” counters Bellamy instantly. “Now, we do a song like [2009 single] Uprising and a year later the news is all about global uprisings everywhere.”

I’m about to ask if he’s claiming credit for the Arab Spring when he beats me to it: “There’s no connection, obviously, but it’s happening. Whether it’s directly caused by music or not remains to be seen. But I could probably tweet something – if I wanted to get arrested – and say: ‘Hey, let’s all go do this outside 10 Downing Street,’ and thousands would probably show up. Anyone well-known in the media can have a direct influence if they want to. We’ve chosen to do it through music rather than other means.”

Such views have occasionally found Bellamy – who Kate Hudson once described as “a complicated farm boy” – hovering around the ‘crackpot’ end of the conspiracy theory spectrum. Most infamously, he once offered the opinion that 9/11 was an “inside job”; he’s since retracted that statement, though the idea of challenging the consensus is still there.

“I’d like to think our songs have some influence on people who feel they don’t need to fall in with everything,” he says. “The structures keeping people in place these days are far more covert and coercive: advertising, the media, the way corporations and governments function, and so on. A lot of young people are born into bondage and don’t necessarily know it. I do feel we’re keeping up that tradition – that it’s the job of bands, musicians, artists in general, to at least shed light on things people might not be aware of.

“I wouldn’t pretend we’re a starting point, but in combination with other artists out there, I think we collectively influence younger people to come up with new ways of thinking. And they’re the ones who will form policies in the future. An amazing piece of art can transform someone, can awaken them to ways of perceiving reality that they hadn’t thought of before. And that someone might go on to be an Obama or a Steve Jobs or someone in a position to make a change. It’s all part of evolution. We’re all interwoven together, evolving in that way.”

That’s not to say that Muse aren’t immune to the more traditional perks that rock’n’roll has to offer. A few years ago, they made no secret of their love of magic mushrooms. And certain members of the band have been known to have fun with ‘the ladies’.

“I’ve never been a heavyweight in that department,” says Bellamy with a laugh. “When I was single for a couple of years I had a lot of fun, but we wouldn’t be on album six if we’d burned out, like many bands do. Dom is still flying the flag pretty strong, even though he might deny it. His idea of a normal week is different from the rest of us. He’s pretty rock’n’roll. But I’d say even he’s trying to calm it down a little.”

Howard considers this. “There have been all kinds of random occurrences over the years, lots of silly excess, yes. Right now, we’re a bit sensible and healthy because the tour’s just started. Once you’ve been on the road for a year, things start to get a little crispy around the edges.”

Before I can ask Bellamy if Kate Hudson has calmed him down, he answers for me. “Anyway, my partner is way more rock’n’roll than me. She likes to come out and get the party going more than I ever could.”

He adds that becoming a dad (his baby’s in-utero heartbeat features on Follow Me, from The 2nd Law) has given him “a reduction in long-term anxiety. I used to be overly concerned about certain things, like…” The impending apocalypse? “Yes, exactly! Things you can’t necessarily control in life. Natural disasters. Elections. Watching your baby from a young age focuses your worries onto something more direct. I’m still interested in what’s going on, but perhaps less emotionally engaged than I was. But who knows, in a few years that might all come back. ”

For all their singer’s new-found domesticity, there’s still little chance of Muse falling into line with convention. The 2nd Law was the most out-there album of last year, its blend of rock operatics, electronic flourishes and tongue-in-cheek excess putting further clear water between them and the competition. The sight of them performing at the Olympics was simultaneously a mark of how far they’ve come and how far out there they are.

“Even we thought playing Survival at the Olympic ceremony in the eyes of the world was odd,” says Bellamy. “It was pretty surreal. Anyone who watches that back will think there’s one thing there that looks and sounds… extreme.”

Inevitably, there’s a gap between the histrionic rock star onstage at the O2, Wembley or wherever and the affable 30-something talking to me in a cafe today (even if, when I mention that I walked past Helena Bonham-Carter just outside, he mutters, “Yeah, she and Tim Burton are our neighbours…”). Does he become another person onstage? Adopt a persona?

“No – if anything, you’re more honest onstage. Up there, the true self comes out. The socialisation levels that we use to modify our behaviour for everyday life can peel away. Onstage you get the chance to see someone’s craziness a little. I like to think when I go and see other artists I’m seeing what’s going on deep down inside them. You get a sense of freedom to express yourself any way you want to. You can say anything you want, do anything you want, behave as you want.”

That, surely, is one of the enduring bullet-points on the manifesto of rock’n’roll.

“It’s only in everyday life,” he concludes, “where you have to put on the jacket, the mask.”

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.