Marillion: The Story Behind Script For A Jester's Tear

The story behind the making of the band's iconic debut album...

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Somewhere amid the flotsam and jetsam of the past, Fish has a collection of yellowing pieces of paper. There are a dozen or so of them,mostly on headed paper, all dating back to the early 80s. They’re the rejection letters his old band Marillion received from every British record company they approached in an attempt to get a record deal.

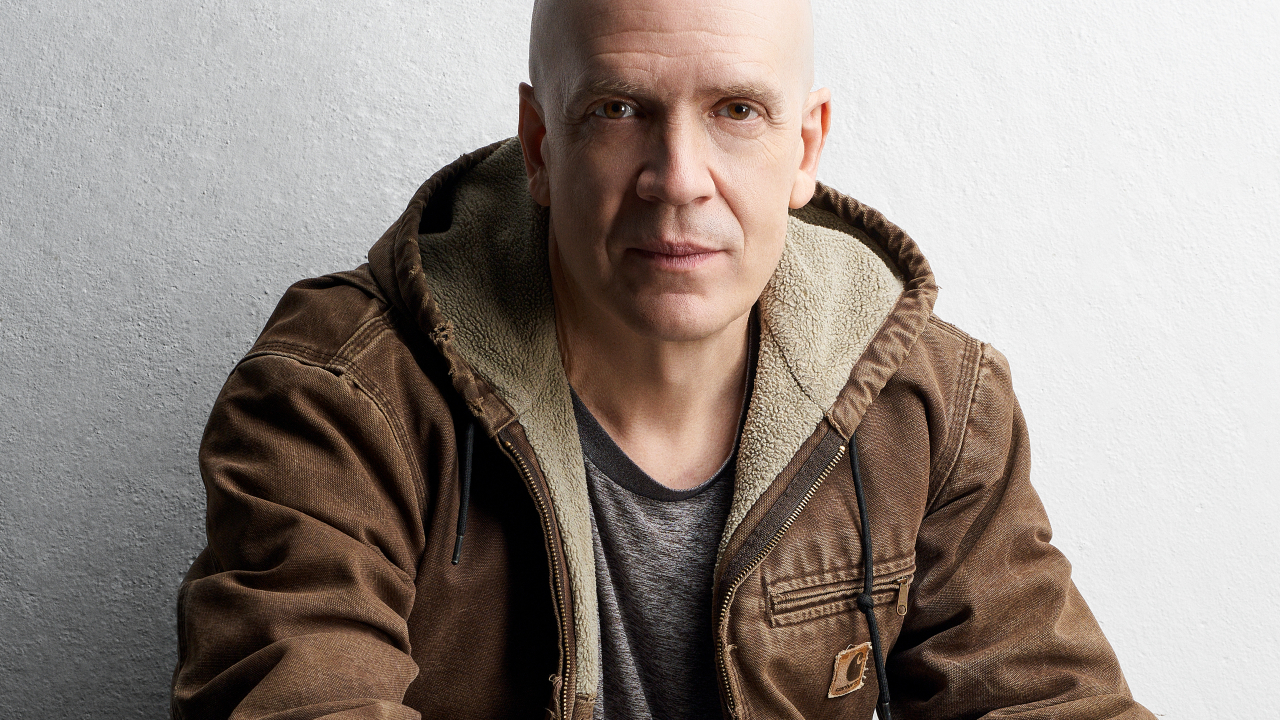

“It was a struggle to get noticed,” says the singer today with a snort. “We weren’t fashionable. I discovered a long time ago that ‘fashionable’ is for short people. But there was a real arrogance about us: ‘We’re gonna make it.’”

That arrogance paid off in spades. Within a couple of years, not only would Marillion be signed to EMI – the biggest label of them all – but they would release a landmark debut album that would give prog a much-needed shot in the arm. That record, Script For A Jester’s Tear, would see this unfashionable five-piece from Aylesbury become the figureheads of a brand new neo-prog movement. They weren’t the first band of their generation to put out a full length album of some sort – Twelfth Night and Pallas beat them – but they were certainly the most successful, and arguably the most important.

Article continues below“I always felt that there was an audience out there,” says drummer Mick Pointer, who founded the band in 1979 and played on Script…. “But the significance of what it became – no, you could never dream of that.

“Lonely” is Fish’s one-word description of what it was like being a member of Marillion in the summer of 1982, a few months before his band entered the studio to record their debut. He had moved down from Scotland a couple of years earlier, winding his way through such musical backwaters as Retford and Kettering before landing in Aylesbury in 1981. He’d moved there to join a band who had, until recently, been known as Silmarillion, until they lopped the first syllable off their name.

As the 80s dawned, prog was on the ropes. The myth that punk had ‘killed’ it has been overstated – prog was doing a good job of killing itself. Its founding fathers had either imploded (Yes, ELP), streamlined their sound so much as to be virtually unrecognisable (Genesis, Rush) or faded into commercial irrelevance (Caravan, Camel). But there were pockets of people who still loved it, and the members of Marillion were among them.

“There were a lot of refugees from the styles that were around at the time,” says Fish. “They weren’t Clash fans, they weren’t Saxon fans. They wanted that little bit more.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

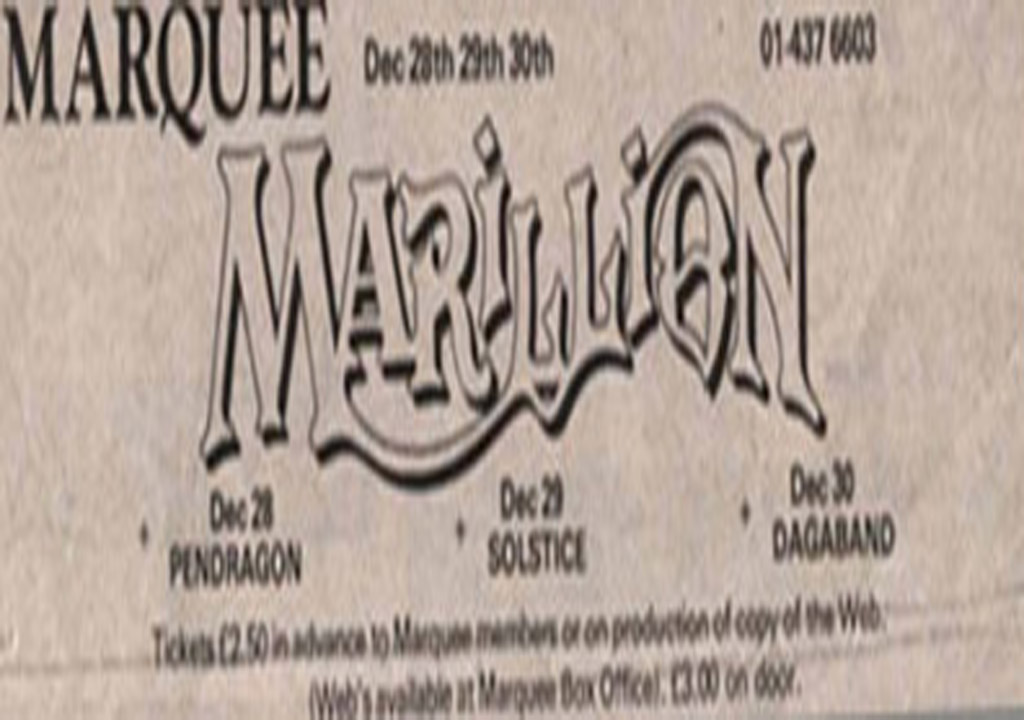

Marillion were ideally positioned to give it to them, although they didn’t exist in a void. There were other bands still holding the prog flame high, no matter how much it flickered: Twelfth Night from Reading, Pendragon from the West Country, Pallas from Scotland and IQ on the south coast. But even then, Marillion stood apart from their peers.

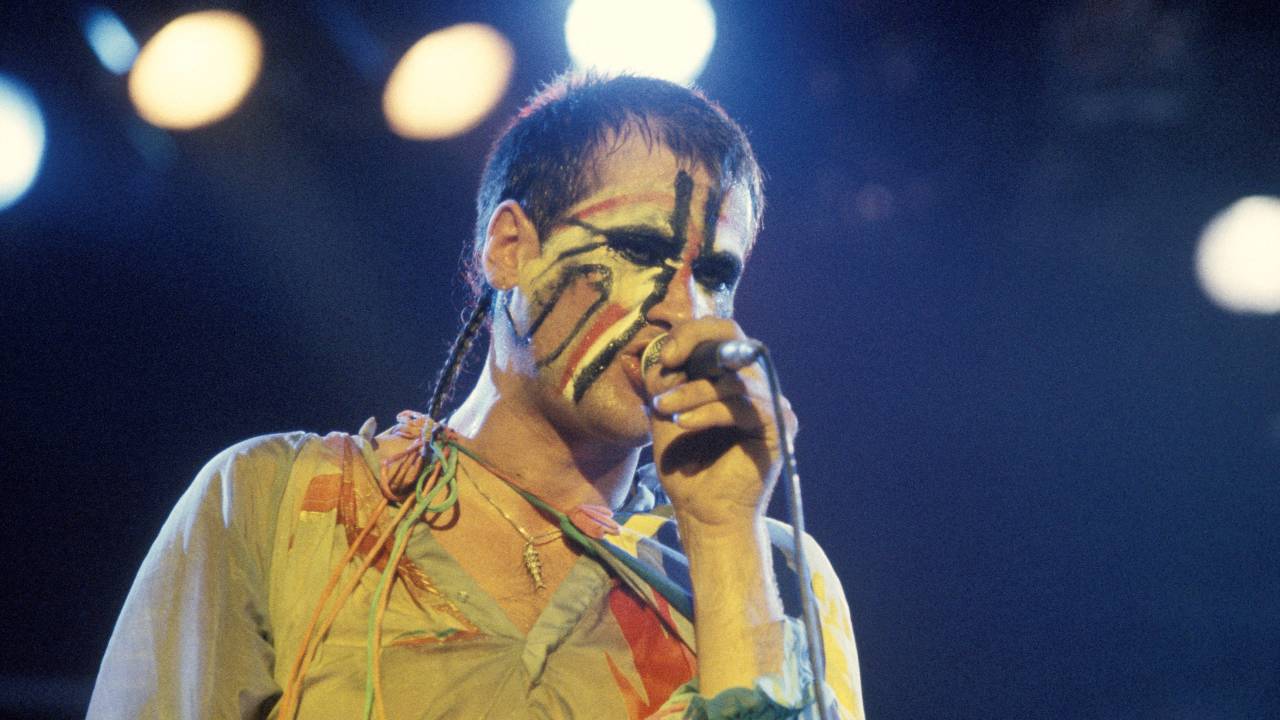

“There was an edge to what we did,” says guitarist Steve Rothery, an original member of the band. “Fish was a very forceful frontperson. There was a different balance compared to some of the other bands around at the time.”

Shrugging off apathy from the labels, the band built an audience the old-fashioned way: by playing live. Fabled London club The Marquee became their home from home. If Marillion had a sixth member, then The Marquee was it.

“Record companies weren’t sure where we could be placed,” says bassist Pete Trewavas, who joined the band in March 1982. “We weren’t necessarily a rock band, we certainly weren’t a pop band. But we were selling out clubs like The Marquee, and we had quite a fan base.”

“There was a business buzz going on about us,” says Fish. “‘Wait a minute, this band is playing to 400 people a night.’ Then we got the radio show with Tommy Vance [a session on the BBC’s Friday Rock Show]. Everything was gaining mass.”

A combination of persistence, stubbornness and the fact that they were rapidly becoming too big to ignore eventually paid off. In the summer of 1982, Marillion were signed to EMI. They had a strong team behind the scenes: former Yes publicist Keith Goodwin championed them in the press, while they were signed to Charisma Publishing by Tony Stratton-Smith, a larger-than-life bon vivant who had played a vital role in the careers of Genesis and Van der Graaf Generator.

But it wasn’t all rosy in the garden. The band had their detractors, with the 19-minute epic Grendel, which appeared on the B-side of the 12-inch version of their debut single, Market Square Heroes, acting as a lightning rod for the critics. Given its similarity to Genesis’s equally convoluted Supper’s Ready, they had a point.

“We were aware of the criticisms,”says Fish. “‘They sound like early Genesis, he sounds like Gabriel, blah blah blah’. I look back on it now and a lot of those criticisms were justified. I mean, Grendel was Supper’s Ready. We were holding onto the skirts of our influences, trying to find the confidence to break away from it.”

By the time EMI installed Marillion in a shared house in Fulham in September 1982 to prepare for their debut album, that confidence was growing by the day, even if living on top of each other was a baptism of fire for the newer members.

“That was interesting,” says Pete Trewavas with a laugh. “Mark [Kelly, keyboard player] and myself hadn’t been in the band for that long, so we were all still getting to know each other. Certain people I got on with quicker than others. I didn’t really know how to treat Fish, to be honest. He was very headstrong. I tended to keep him at arm’s length.”

Inevitably, the band had chosen The Marquee’s in-house studio to record the album. For Fish, it was the perfect location.

“The bar was definitely my watering hole,” says Fish. “Charisma Records and Charisma Publishing were upstairs, so I’d pop up to see all my mates. We’d go into the club at night to see bands and work in the studio until two or three in the morning. It added to the gang mentality.”

Nick Tauber had been brought in to produce the record after David Hitchcock, who had worked on Market Square Heroes, was injured in a car crash. Tauber produced Thin Lizzy’s early records, though he’d recently had success new wave banshee Toyah.

“Nick was brilliant,” says Fish. “He was like an uncle. He filtered out some of the superfluous bits, he helped with the sound and the layering. It just added to the whole momentum of it all. Script For A Jester’s Tear contained just six songs, only one of which, future single He Knows You Know, came in at under seven minutes. All of the songs had existed in one form or another for a year or more, with the exception of the title track, which was inspired by Fish’s turbulent love life.

“I was getting involved in my first serious – and I mean really serious – relationship, and all the questions and issues that brought with it. There was a lot of introspection going on in the lyrics. If I look back, it was put across in a very naïve way.”

While the band paid lip service to their influences – not least in Mark Kelly’s keyboard textures and Steve Rothery’s restless guitar work – there was a distinctly modern feel to it. This was new music for a new decade

“There was a kind of punk thing, a real spit and venom about it,” says Fish. “It might have been all clever-clever music-wise, but the delivery had a lot more attack. There was a lot of anger and aggression and angst. I’m Scottish. It goes with the territory.”

It was that anger that set Marillion apart from what had come before them, as well as their peers at the time. Discarding the whimsical window dressing of the previous generations, Fish’s lyrics veered between rage, frustration and heartbreak. The bleak, gloomy fanfare of The Web (‘The rain auditions at my window/Its symphonies echo in my head’) was a prog bedsit anthem; Chelsea Monday was the tale of a doomed rich girl, inspired by a newspaper headline Fish read on one of the amphetamine- fuelled early morning walks through London he had taken to going on; He Knows You Know sweated junkie paranoia from its every pore; the lengthy, livid Forgotten Sons was ostensibly a protest song about the situation in Northern Ireland, though it could be read as a furious critique of the Thatcher government.

“I wasn’t the clichéd art-school person you normally expect in a prog band,” says Fish. “I wasn’t part of the Charterhouse squad. I was Scottish working in England. I felt a certain amount of isolation.”

His ire was most apparent in the juddering Garden Party, the second single from the album and arguably its highlight. A pointed broadside at the upper classes, it was the anti-Brideshead Revisited: a furious, sarcastic class-war anthem that punched and jabbed like a Muirhouse street fighter. It had been conceived during an ill-fated trip to Cambridge a few years earlier.

“I was going out with a girl down there in 1980,” he says. “Diz [Minnitt, Marillion bassist between 1981 and 1982] and I both ended up staying in a Halls Of Residence. We figured there was more chance of getting musicians together and finding gigs. It was really naïve – clutching at straws, so to speak. I always had a chip on my shoulder about blue bloods, the whole class thing.”

It wasn’t all angst and frustration. “There was a whole Floyd mentality to it,” says Fish. “Which was, ‘Let’s do this crazy shit. Let’s record the secretaries from The Marquee at the beginning of He Knows You Know’.”

For Forgotten Sons, they needed someone for the part of the newsreader. Their first choice was ITN anchor Trevor McDonald.

“Yeah, but he was too fucking expensive,” says Fish. “We didn’t have the budget, so we ended up listening to these tapes of actors doing voiceovers. There was one guy saying, [posh TV announcer’s voice] ‘Applecake’. We said, ‘That’s the guy!’.”

The guy in question was Peter Cockburn, whose CV included as a TV announcer on ATV, as well as a cameo appearance in Carry On Camping.

But it wasn’t all plain sailing. Tensions were growing between one of the band’s founders and the rest of the group.

“If you had walked in during the drum recording, it would have been quite stressful,” says Fish. “There had been issues with Mick Pointer’s drumming around the time of MarketSquare Heroes, and when Nick Tauber came in, the first thing he said was, ‘We’ve got a problem with Mick Pointer‘. People tried to deal with it in a subtle way: ‘Mick, do you think you could take some drum lessons to discover some different aspects to drumming?’. That went down like sick in a space suit. That brought an added tension to things. Everybody was walking on eggshells. There was a lot of animosity from Mick towards the rest of the band. He thought he was being betrayed, but he was still in the band. People wanted us to get rid of Mick before we did Script…, but the band stuck by him.”

Mick Pointer says that he doesn’t recall any arguments in the studio. But after the end of the Script… tour, he was no longer the drummer in the band he had founded a few years earlier.

The members of Marillion have different memories of the first time they listened back to Script…. In typically modest fashion, Steve Rothery recalls being quietly impressed: “I was really pleased with what we’d done.”

Pete Trewavas doesn’t remember his reaction, though he does recall the first time he heard Garden Party on a car radio: “We all piled around this car with the doors open, listening to us being played on the radio.”

The first time Fish heard it from start to finish, he cried. “They played it back in the Marquee studios,” he says. “I remember going through to the lounge and having a manly weep.”

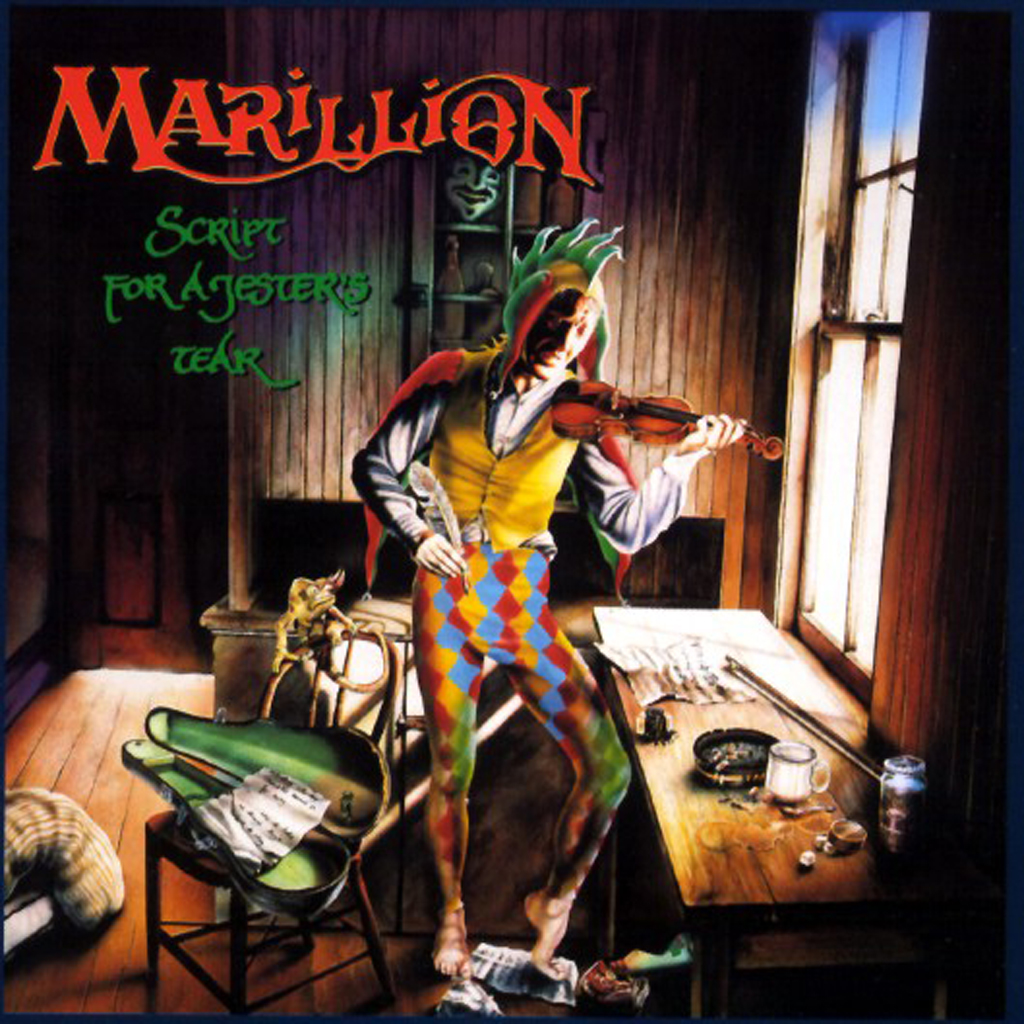

When the album was released on March 14, 1982, housed in an iconic sleeve featuring a painting by Mark Wilkinson, it polarised opinions in the press, if not among prog fans.

“The NME hated us and what we represented,” says Fish. “They thought we’d been killed off. They objected to the fact that we’d raised our progressive rock heads.”

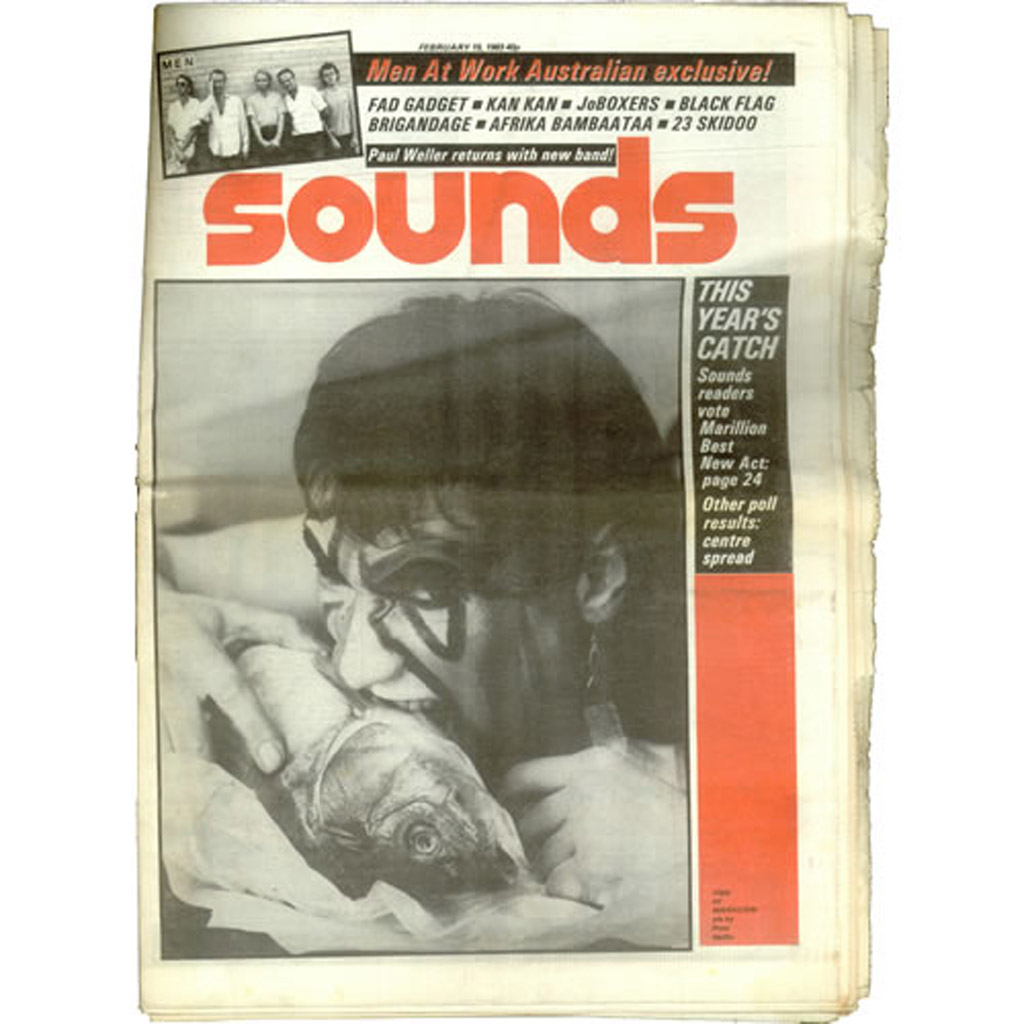

By contrast, Kerrang! and Sounds heralded Marillion as the figureheads of a new prog revival. That didn’t sit well with Fish.

“I never saw us as being champions of anything,” says Fish. “We were just doing what we did, and doing it really fucking well. You’ve got to remember that we were streets ahead of anything else that was around us. We hit the Hammy Odeon on the Script… tour. There was nobody else coming close to playing those kind of numbers.”

Whether he likes it or not, it’s hard to argue with the impact Script… had on the prog scene. Not only did it give those “refugees” something to celebrate, but it also went a long way to resurrecting a commercially moribund genre.

“Everybody was into new wave and American stuff,” says Pete Trewavas. “Record companies didn’t know what to do about all that other stuff that used to be popular. What we did was make other labels realise there were more types of bands you could sign.”

Indeed, the success of Script… opened the floodgates for what would be dubbed neo-prog. It would soon be joined on the racks by albums from Pallas, Twelfth Night, Solstice and more, though none would come close to Marillion’s success. For the next two years, they were the public face of neo-prog, until a track about an ex-girlfriend of Fish’s named Kay Lee took them to another place altogether.

“I never really looked on it as being ‘carrying a flag’ at any point,” says Fish. “From my perspective, it was just what I wanted do. It was the music I was happy playing.”

This was published in Prog issue 35.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.