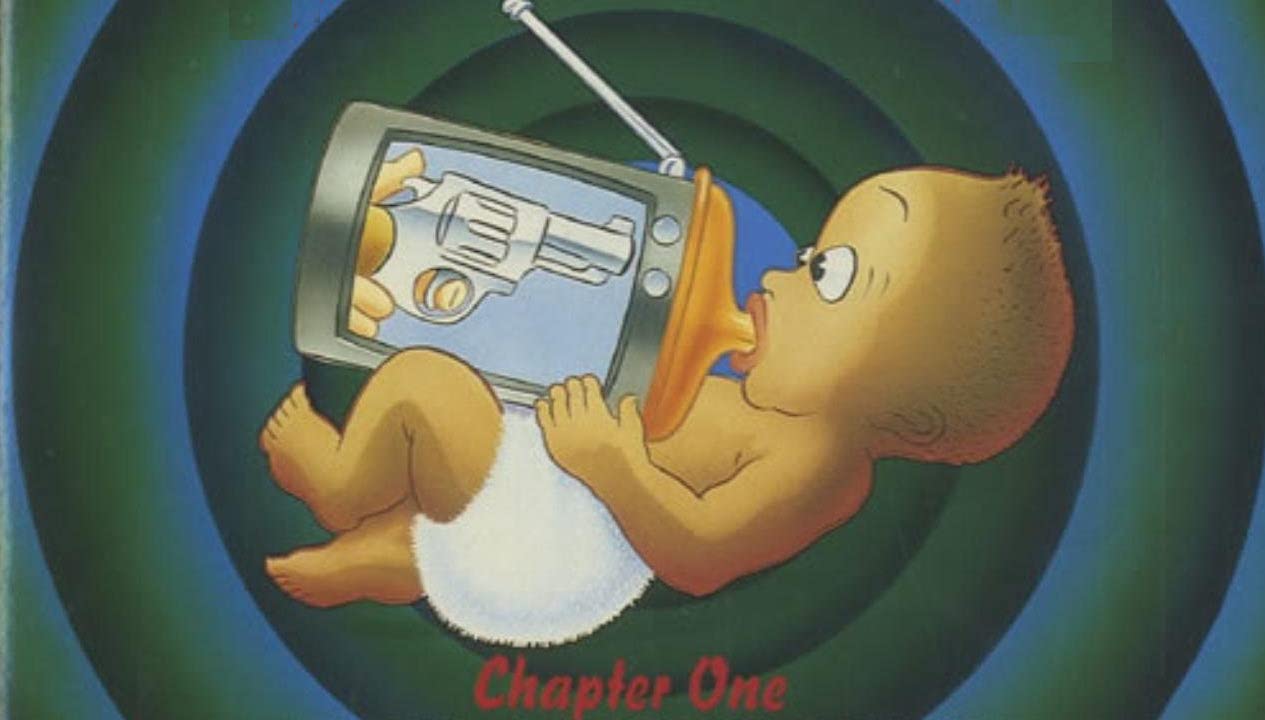

No-one remembers them much these days but 30 years ago The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy’s Television, The Drug Of The Nation was part of a two-pronged movement that was turning rock fans onto beats and raps, and introducing black artists to formerly all-white record collections.

Television, The Drug Of The Nation was like the Dead Kennedys with groove. The NME voted it the 7th best track of 1992 and its parent album Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury was no.11 in their Albums of the Year list and no.3 in Melody Maker’s list, ahead of Pavement’s Slanted & Enchanted, Ice Cube’s The Predator, the Manics’ Generation Terrorists, The Lemonheads’ It’s Shame About Ray and other more fondly-remembered albums of the time.

Offered a support slot on U2’s Zooropa tour, The Disposables went from playing clubs to performing in front of 50,000 people a night, with Bono joining them onstage for signature track Television. And then? Well, nothing much. But their work here was done.

It was confusing being an alternative rock fan as the 90s began. To those of us who became teenagers after punk, the worst excesses of rock’n’roll were not only back, they were obvious and everywhere (and looking older by the minute). Bon Jovi, Aerosmith, Motley Crue? Rich white guys with big hair and shit-eating grins. This wasn’t the revolution we’d been promised.

In fact, the revolution was coming from two different but similar directions: Electronic music and hip-hop.

Electronic music had mutated into something more than ‘mere’ synth pop – it was a truly futuristic sound, with huge beats and rib-quaking bass. And hip-hop was more punk than actual punk: more rage, more attitude, better lyrics.

Some rock bands could feel the wind changing. By the late 80s in the UK, rock bands like Big Audio Dynamite, Pop Will Eat Itself, Jesus Jones and Gaye Bykers On Acid had started embracing big programmed beats and basslines, and threading their music with samples. They showed that it wasn’t either/or. In the words of PWEI’s Can U Dig It?, they dug Marvel and D.C., Renegade Soundwave and AC/DC.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Elsewhere, industrial was brewing. The punks had gotten their hands on drum machines. The whole DIY punk ethic fitted perfectly with programming and using samples. Weird anti-establishment bands like Finitribe, (pre-Mr C) The Shamen, Tackhead, Meat Beat Manifesto, Nitzer Ebb, Front 242, Young Gods, Revolting Cocks, Ministry, Consolidated and more were busy making music for IBM (Intense Balding Men) and bringing outrage and punk rock attitude to this new electronic revolution.

But, Tackhead aside, these were mostly white guys. The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy were black, formed from the ashes of The Beatnigs, an art-punk collective whose debut album came out on the Dead Kennedys’ Alternative Tentacles label, at a time when you could count the number of black punk artists on one hand.

Frontman and lyricist Michael Franti had grown up in love with “the storytellers that could make you dance,” he told DJ magazine. “Stevie Wonder, Santana, War, John Lennon, Johnny Cash…Then I discovered The Clash. They were using reggae, punk, R&B, Latin grooves, jazz and rap — and this political voice.”

Based in San Francisco and inspired by the industrial sounds of Einstürzende Neubauten and Tackhead as much as by Public Enemy, The Beatnigs used scrap metal from the Bay Area’s dying shipping industry for percussion. “We were like, ‘Let’s grab some scrap metal and just fucking beat shit out of it’,” said Franti. “We loved hip-hop, but we didn’t use drum machines.”

The Beatnigs’ big track was called Television – it was on the Terminal Ricochet soundtrack album, next to songs by US punks DOA, Nomeansno and Jello Biafra – and when the band split, Michael Franti and Rono Tse formed The (let's be honest, appallingly named) Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy. With Mark Pistel of Consolidated on programming and arrangements, they re-tooled Television for the new decade.

Parallels were drawn between Television, Drug Of The Nation and Gil Scott-Heron’s The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, but where Scott-Heron was impressionistic, The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy were more literally-minded.

Television, it claimed, was “the drug of the Nation, breeding ignorance and feeding radiation”. Chuck D once said that rap was black America's CNN – "informing people, connecting people, being a direct source of information" – and The Disposables took that literally: “T.V. is the reason why less than ten percent of our nation reads books daily,” goes the lyric. "Why most people think Central America/means Kansas/Socialism means unamerican/and Apartheid is a new headache remedy.”

A decade on from Pink Floyd’s “Got thirteen channels of shit on my TV to choose from,” Franti rapped:

150 channels 24 hours a day

You can flip through all of them

And still there's nothing worth watching.

Both Floyd and Franti's lyrics might seem quaint today, with 37 million barely-regulated YouTube channels to choose from, but it doesn’t mean their concerns were unfounded. “Ronald Reagan was President at the time,” Franti explained, “and he could convince the country of almost anything.”

Rap may not have been CNN but it did serve notice on rock’n’roll. It was cooler, more dangerous, lyrically smarter, sonically new and its rage was real and justified. Looking back years later, Franti commented that the Disposables "were a bit like broccoli – people were into it because they thought it was good for them”. But the truth was, they were good for us.

Television was the moment a lot of rock fans finally embraced hip-hop. Listeners to the John Peel show voted it no.38 in that year’s Festive Fifty. Follow-up single The Language Of Violence was at no.30. 1991's Festive Fifty had been 100% indie and alt.rock bands – without a single black artist, hip-hop or electronic act. In 1993, Chumbawamba & Credit To The Nation's anti-fascist anthem Enough Is Enough was number one and the chart included Senser, Transglobal Underground and more. The door had been kicked open.

Tom Poak has written for the Hull Daily Mail, Esquire, The Big Issue, Total Guitar, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer and more. In a writing career that has spanned decades, he has interviewed Brian May, Brian Cant, and cadged a light off Brian Molko. He has stood on a glacier with Thunder, in a forest by a fjord with Ozzy and Slash, and on the roof of the Houses of Parliament with Thin Lizzy's Scott Gorham (until some nice men with guns came and told them to get down). He has drank with Shane MacGowan, mortally offended Lightning Seed Ian Broudie and been asked if he was homeless by Echo & The Bunnymen’s Ian McCulloch.