How Fish drew inspiration from family WWI experiences for A Feast Of Consequences

Fish talks us through the terror of almost losing his voice and how he drew inspiration from both his grandfather's WWI experiences for the personal A Feast Of Consequences

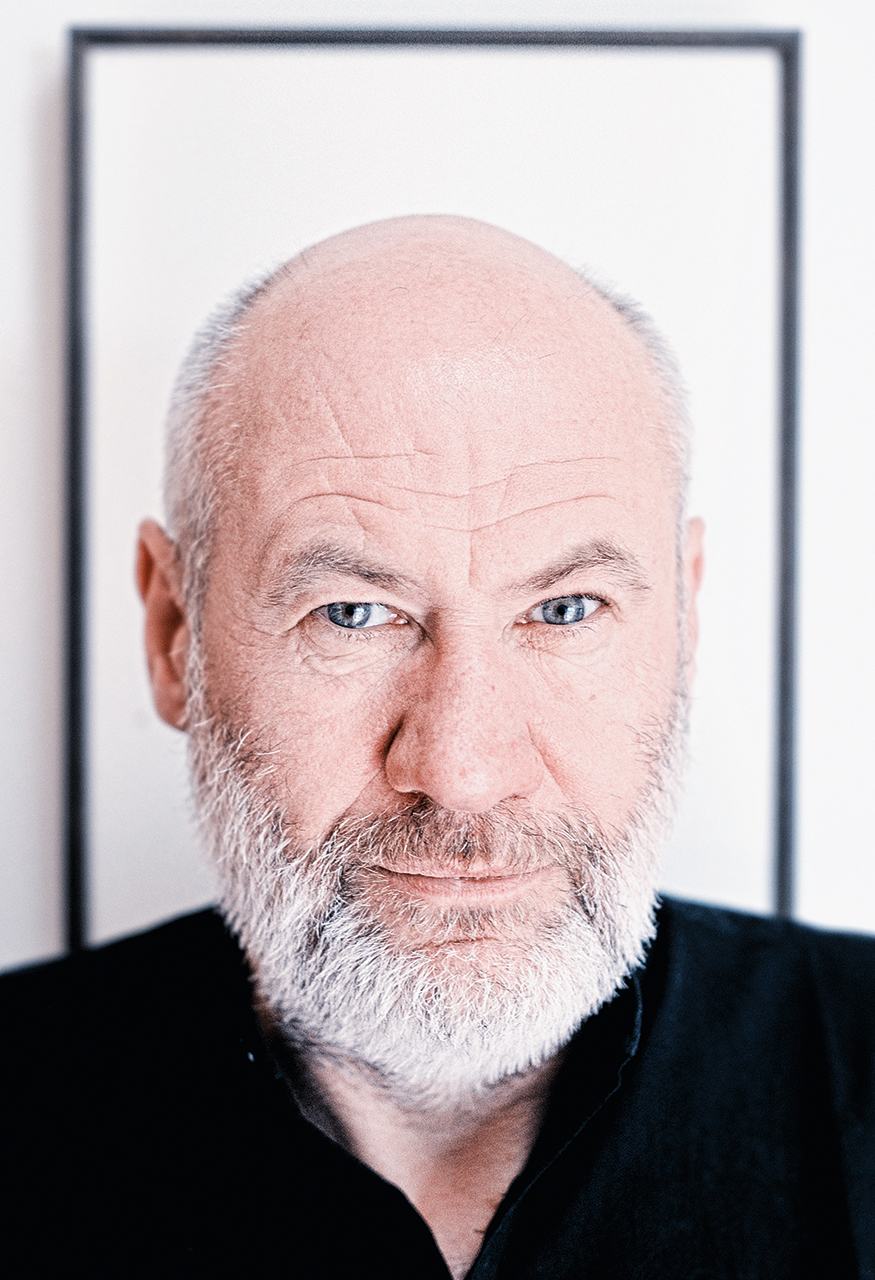

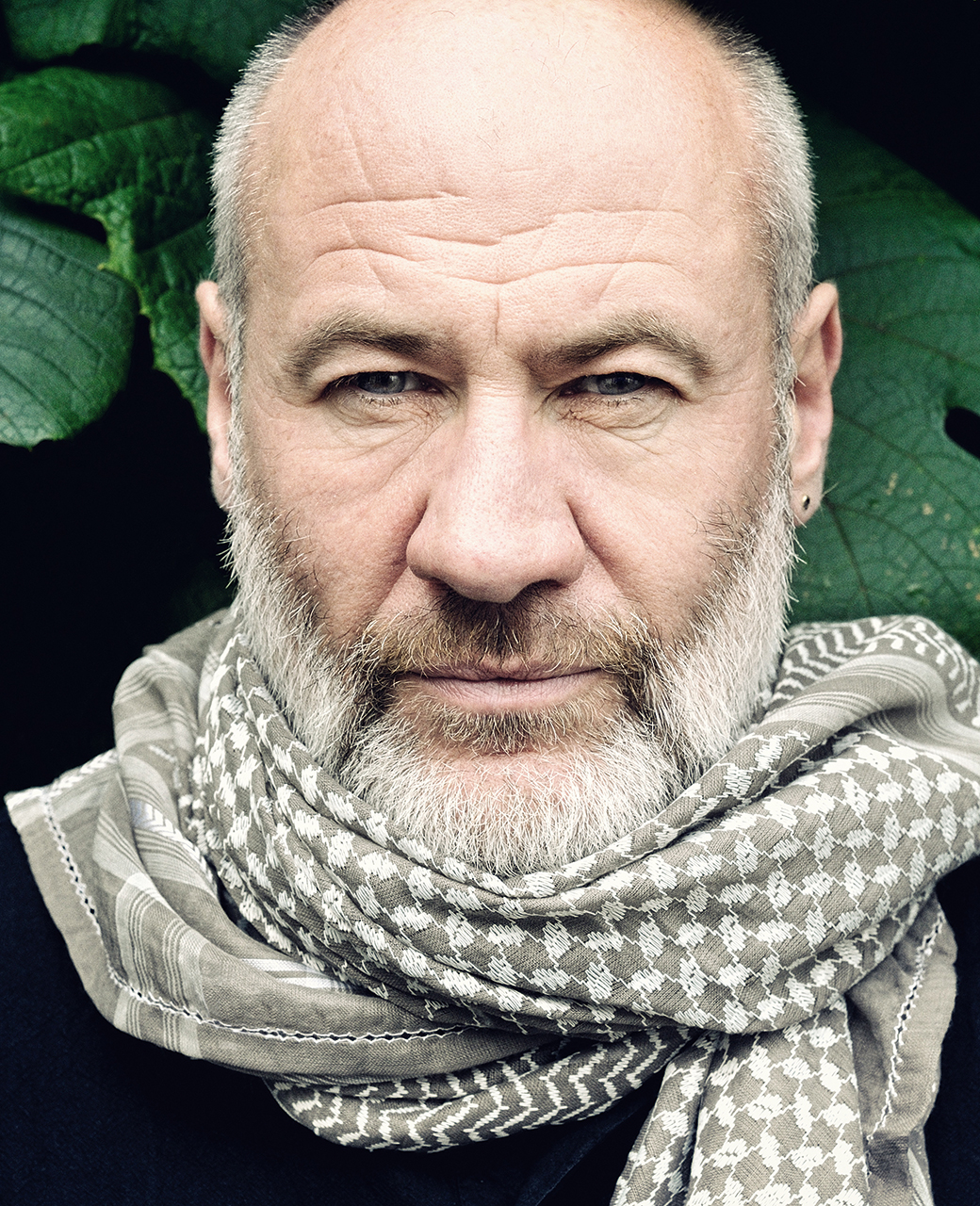

Fish appears, quite unexpectedly, from a veritable forest of lettuces and cherry tomatoes, clutching a substantial watering can. Prog is at his studio home in rural East Lothian, within the shadows of the distant Lammermuir Hills, and the wonderfully self-sufficient surroundings are close to drifting into a scene from The Good Life.

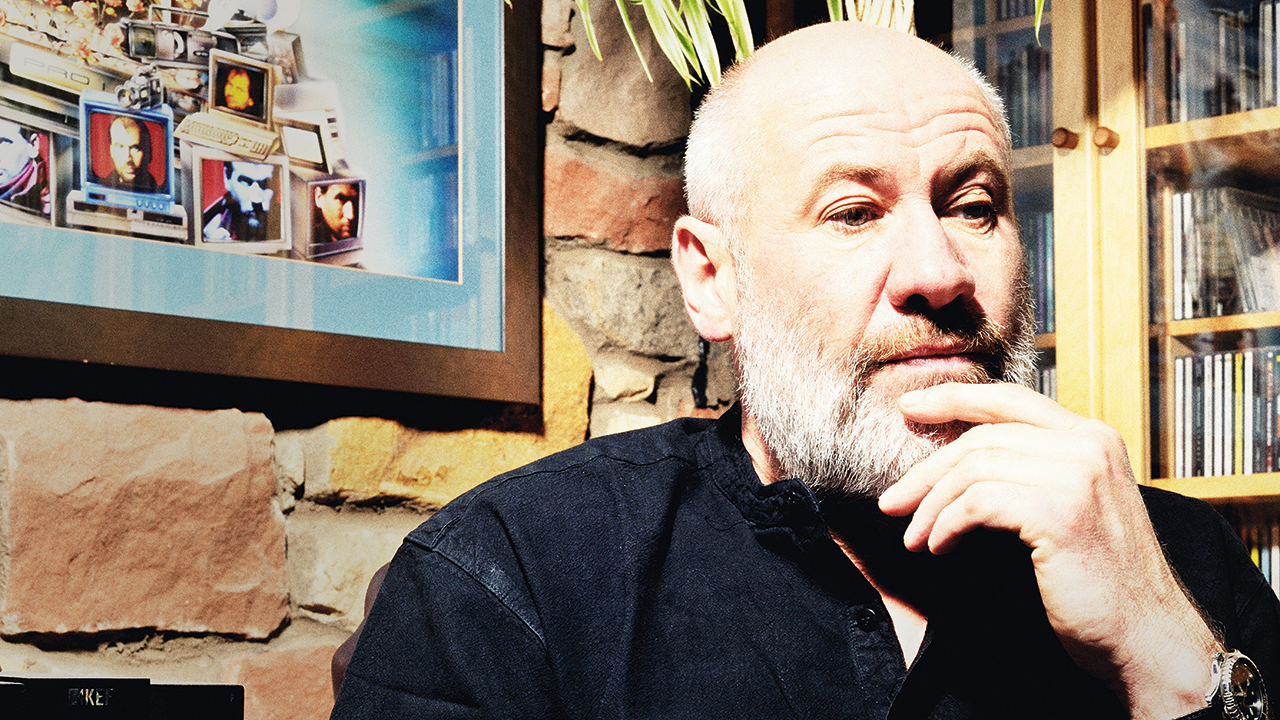

Fish is positively bouncing, visibly buoyed and enthusiastic about his new album, and clearly still adoring his existence in the place that he bolted to when the furore from his Marillion departure was exploding 25 years ago. It’s unquestionably a man cave, album art work and gold discs adorning the walls, with the hollow stare of the helmet he wore during performances of Grendel peering down quizzically from a shelf.

“One of the reasons I left Marillion was that I couldn’t stand being in the machine, being ground up by all the cogs,” he confides. “I like this. I love the freedom and I really don’t need a lot to keep me going. I mean this is it, and it isn’t a fucking mansion. I don’t really have a pension, I’m facing the twilight years of my life with no real back up and the reality is that I’m never going to retire. But you know, apart from all the rip offs, it’s been a great life.”

Those ‘rip offs’ that Fish casually mentions have been pretty relentless, often harsh and at times career threatening. Two divorces, tour promoter collapses on the eve of tours and debts that ran in hundreds of thousands of pounds necessitated the selling of his main house, with Fish moving into this adjacent studio that now doubles as his home. There was also the financially crippling legal action against EMI in the early 1990s which, as he attests, left him a “miserable, nasty bastard”. Even more alarming were the problems that have beset his voice over recent years and delayed the writing of new material. The troubles really took hold during the 2008 tour, when his voice would intermittently falter during gigs.

“Every night, at nine when I went out on to the stage, I never knew how my voice was going to be, and I was getting paranoid,” he remembers, perching himself on a settee adjacent to a surprisingly intact rubber plant. “It wasn’t that I was over-indulging, and I had to take a shit-load of ibuprofen every day to keep the swelling down. By the time it got to the end of the tour, it was freaking me out and I was getting really depressed. I wanted to leave and give the whole thing up. I remember the last gig was in Buxton, I came off stage and I was nearly in tears. I just felt I couldn’t do it any more and I didn’t want to go on stage. When you’re singing, there’s nothing worse than when your voice is fucked. You’re facing the audience and you can see people cringing and going: ‘Ooh, you fucker’ when you’re trying to hit a note. I really felt that I was letting them down.”

Suspecting there was more to the problem than simply age or the rock lifestyle, Fish was persuaded to see a hospital specialist and it was discovered that there was a growth on his vocal cords. After two operations, the cyst was removed, only to return, before finally disappearing in 2010. As Fish points out, an overbearing threat of a cancer diagnosis or suffering permanent damage to his central, career tool made for a tormenting time.

“That was everything, my singing career, my acting career and the radio work,” he sighs. “My voice is everything and it wasn’t the smoking or the alcohol that had caused it, although they weren’t exactly positive factors. It was just wear and tear and stress combined over the years. Before they operated the first time, I spent two months thinking: ‘this is it’. The doctor told me that it was a cyst and had been there for up to two years. So I had been singing, for two fucking years, with a cyst on my throat. I think the only reason I was keeping my shit together was because of the ibuprofen I was taking every day. I couldn’t hit the high notes because there was a big lump on my cord and I had no idea.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Listening to Fish relate road tales from over the years – ranging from legitimate gangster-related death threats, gigs in Mogadishu, through to the comically libellous which will make his long-promised autobiography vital reading – it’s tricky to perceive a time when he was short on confidence. Yet fearing his voice may crack under the pressures of live performances, his self-belief was shot. After escaping to such destinations as Costa Rica, Cuba and Vietnam, it took a string of acoustic dates to restore his normal swagger.

“I stopped smoking, started scuba diving, got into hill walking and did the West Highland way, which is about 100 miles. It was the fittest that I’d been in years. But the thing was, I knew eventually that I had to go back to do my job, but I was really nervous and unconfident. So I thought that as I didn’t have any new material, rather than go back into doing a full electric set, it was the perfect time to do an acoustic tour. There were little costs and even though we were playing to less than 100 people, I loved it. It was intimate, I was talking to an audience, people were laughing, the music really worked and it was building me up again. That tour probably went on longer than it should have done though, as I think I was avoiding the fact that at some point I had to go back in and do an album. It was like the longer I stayed on the road, the longer I didn’t have to write the fucking album. It was a huge concern.”

Health issues aside, he also had a reticence to commit to a studio project until he felt he had amassed enough in his black book of ideas to release something worthwhile. Never an artist to churn albums out every 18 months simply to retain a constant income stream, he recalls that he needed a fresh focus for the writing.

“People ask me why it’s taken me six years to put an album together and why I didn’t do one three years ago,” he says. “Apart from all the other problems, the reason is that it wouldn’t have been any good, resonated or lasted. I wanted to do something that was meaningful and that I would be proud of, and that was why I held off. There are many bands out there would put an album out that’s really just an exercise in continually financing. I’ve always avoided that, with Songs From The Mirror [1993’s contractual obligation album of cover versions] being the only one, which was the fox eating his leg off to get out of the trap. 13th Star had been a relationship album and I just thought I don’t want to do that again. It was like there were these dark threads, like tendrils, reaching out. Everything I wrote ended up in that dark fucking well and I had to stop writing. I had to find a new thing, and that was found by travelling. In Cuba, I was just on my own, drinking daiquiris and walking in the footsteps of Hemingway. I love photography too and that was really helping. I was wandering around Havana at night on my own, just taking photos of people. Just capturing images all the time, and those photos really helped me when it came to writing. It’s just observations and they all help trigger things.”

Fish also explains that a visit to the Somme battlefield in northern France would provide some of that inspiration he’d be searching for that would become A Feast Of Consequences. He spent several days there and it provided the necessary subject matter for the central, twenty-odd minute, High Wood suite of five songs that forms the core of his new album. In typical fashion, Fish completely immersed himself in the subject, reading countless books and spending weeks on research.

“That is a bullet that killed someone,” he says solemnly, handing a grotesquely twisted, 1916 rifle round to Prog, adding a stark, physical poignancy to the conversation. “That battle was utterly horrific and 60,000 men were killed or wounded on the British side alone. We spent a day walking around all the trench lines and I would never, ever have believed or comprehended how much a place could have an affect on me. I went to the cemetery on my own and I was in tears. I was wandering around and crying my eyes out. It had a real effect as you can see even now.”

There was more to come. Aware that both his grandfathers had served with the forces during the First World War, a conversation with his parents combined with some research led to him making one of a series of bizarre coincidences.

“We stayed the night in a house, which was built on what was No Mans Land,” remembers Fish. “I woke up the following morning really early, it was my birthday and there was a light mist all over the ground. I just sat there staring at the view. I phoned up my mum and dad and told them where I was, and I found out what battalion my grandfathers were in. What I found out was that when I woke up that morning and looked out through the French windows, I was 150 metres away from where my granddad dug the White City trench line. Out of all the fucking places, on the whole of the Somme, I spent the night there.

“Later that day, I spotted this dark wood on the top of a ridge which really stood out, which I found out was called The High Wood. The shelling there was so intense that there are 8,000 men who were never found in a space the size of six football pitches. After I got home, I found out that my grandfather had dug a trench there. They were digging through bodies in the middle of the night in pitch black. It was just heads, fucking torsos, and they were digging through this shit. He never talked about it, and every time I listen to the new song Thistle Alley, my eyes just go straight to that photograph of him on the wall. The unbelievable, soul destroying horror that those people went through. It’s more than coincidence you know? It’s weird and sends a shiver up your spine when you put all that together. There’s just too much and I feel that I was meant to write this.”

Concocting suitable lyrics for a piece that dealt with such mass loss of life also posed problems. They had to convey the bleak realities without resorting to the type of formulaic verses that might come across as a crass attempt at hackneyed storytelling. To counter that, Fish referred back to the poetic writings of the time.

“I was reading Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, and I decided that rather than write a clichéd heavy metal thing, I was going to approach it from the style that was of the early 20th century,” he insists forcefully. “I really wanted to deal with the subject in a really respectful manner and to write something substantial. It just became so important to me.”

It’s clear Fish considers he’s approaching a crossroads. There’s talk of acting work, spending more time in Germany with his girlfriend, and writing screenplays. For now though, his focus is on touring, as the nicotine inhaler and glass of cranberry juice that form part of his current health regime are testament to. Every artist will claim their latest album is their finest, but Fish has the swagger of a golfer who knows he’s got it in the hole before the ball even lands.

“Honestly, if I was to have a last album, this would be it. If I was going to walk away and go: ‘Right, that’s me, I’m not doing any more’, then I’d be happy to leave it at that.” He says this sincerely, briefly pausing before ambition gets the better of him. “The big problem that I’ve got now is that I’ve got to beat this…”

This article originally appeared in issue 40 of Prog Magazine.